Interview by Alexandra Schwartzbrod

In Drone Theory, the philosopher Grégoire Chamayou examines the legal and moral questions raised by a weapon that confers unilateral physical immunity.

Grégoire Chamayou, researcher in Philosophy at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), just published Drone Theory, a continuation of his earlier essay Les Chasses à l’homme (Manhunts). Therein he addresses the psychological, ethical, and legal problems that this weapon of modern times presents.

AS: How and why does philosopher become interested in drones?

GC: The “Unidentified Violent Object” that is the drone throws traditional categories of thought into crisis. An operator pushes a button in Virginia, and someone in Pakistan dies. Since the act of killing is split between such distant points, where does it take place? This produces crises of intelligibility that philosophy must account for. Drone Theory is the continuation of an earlier book called Les Chasses à l’homme (Manhunts): the armed drone is the emblem of contemporary militarized manhunts. There are philosophers in the US and Israel who work hand in hand with the military to develop what I call a “necroethics” that seeks to justify targeted killings. Therefore there is an urgent need to respond. When ethics is enlisted in the war effort, philosophy becomes a battlefield.

AS: Are militaries under this much pressure to justify the use of drones?

GC: The drone appears as the weapon of choice of the coward, he who refuses to show himself. It requires no courage; it deactivates combat. This provokes deep crises in terms of military values. But the military needs justifications. It is here that “military ethicists” come in: their discourse serves to lower the damage in reputation that’ comes with using a weapon that is perceived as heinous. And this at the cost of turning the very meaning of words on their heads, since they argue that the drone – an unmanned machine – is the most humane of weapons.

AS: How did the US come to develop the use of drones?

GC: After 9/11, Bush declared that the US had entered the age of a new form of war: an international manhunt. This was not just a slogan. Strategists defined the corresponding doctrine, one no longer focussed on combat, but on tracking. The idea is to assume the right to pursue quarries all over the world, regardless of national borders. Today the hunter-killer drone is an instrument of the White House’s unofficial anti-terrorist doctrine: kill rather than capture. You can’t take any prisoners with a drone. When Obama says he wants to close Guantanamo, it’s because he has chosen the Predator drone in its stead. The problem of arbitrary detention is solved with extrajudiciary executions.

The question that arises is the democratic sovereign’s right to kill. The debate is very animated in the US from the moment that drones have been used to kill American citizens. When you can kill your own citizens abroad, outside the context of legitimate defense, where is the limit? Can this type of weapon be used on national territory for example? Police drone projects are beginning to show up… Thus we see the emergence of a broad opposition in the US, comprised of defenders of civil liberties, the anti-war left, but also the libertarian right.

AS: In France, strangely, there hasn’t been any debate on this topic…

GC: The public knows very little. But Jean-Yves Le Drian wants to buy American Reapers, which is to say hunterkiller drones, not surveillance drones. We are told that they will be sold unarmed, but this is a requirement to accelerate the export process. It will be enough to just equip them later. It bothers me is that this type of decision is not publicly debated. If a Defense Minister had announced his intention to import the CIA’s torture techniques, it would have caused an outcry! A government cannot decide to take up weapons like this without a public debate. Even when it comes to details, questions arise: Who will train the operators? Which countries will they direct their machines from? If they are trained by Americans, does this mean that France will adopt the same type of strategy?

AS: What strategy are you referring to?

GC: The drone has become the weapon par excellence of American-style counterinsurgency war. The landcentered paradigm of the past gives way to an aircentered model: control from above instead of occupation. Even if this is not well known in France, there currently is an intense debate amongst US counterinsurgency strategists. Some even demand a moratorium on the use of drones, following the lead of David Kilcullen, a former aide to General Petraeus. They worry that a strategy is being replaced by a gadget, while underestimating the counterproductive effects this has on populations. Drones, by imposing an indiscriminate terror, are not very good at “winning hearts and minds” and end up paradoxically feeding the danger they are supposed to eradicate. Defenders of aerial counterinsurgency retort that it is enough to “mow” regularly: strike as soon as new heads grow back. The promise is of a war without defeat, but it will also be one without victory.

AS: Do we have enough distance on this form of war to learn anything from them?

GC: Yes, we are fortunate, in a sense, to have more than ten years of distance. In Kosovo, in 1999, drones were only an instrument of surveillance and reconnaissance. The Predator spotted the targets, but it couldn’t shoot. This is where the idea of equipping it with antitank missiles took root. Around 9/11, the new weapon was ready; the Predator had indeed become a predator. This genealogy is very informative: Kosovo was aerial warfare with zero direct casualties in the NATO camp. NATO decided to fly their planes at 15000 feet, out of range of enemy fire, at the cost of airstrike precision: the lives of the pilots were placed above the lives of the Kosovar civilians that were supposed to be protected. Theoreticians of “Just War” were scandalized by this new principle of immunity for the national fighter. At the time philosopher Michael Walzer asked: Is war without risk permitted? He cited Camus: one cannot kill if one is not ready to die. This is a metajuridical crisis concerning the right to kill.

AS: What do you mean by that?

GC: War is defined as a moment during which homicide is decriminalized under certain conditions. If we grant the enemy the right to kill us with impunity, it is because consider ourselves to have the same right with respect to him. This is based on a relationship of reciprocity. But what happens when this reciprocity is annulled a priori, in its very possibility? War degenerates into slaughter, into execution.

The question that arises for the American administration is: what legal framework do these strikes take place in? When asked, the administration refuses to answer. So what would the conceivable legal frameworks even be then? There are just two possibilities. The first is the law of armed conflicts, where the use of weapons of war is only allowed in zones of armed conflict. The problem is that US strikes in Yemen, Pakistan, etc. are taking place outside of a war zone. Another principle: it is forbidden for civilians to take part in armed conflict. Yet, a major part of the American drone strikes is conducted by people from the CIA – civilians. They could therefore be pursued as war criminals. The second possible framework is that of law enforcement, generally speaking, police law. But degrees of force are required there: capture before killing; use deadly force only as a last resort, when confronted by a direct, overwhelming and imminent threat. With the drones however no gradation is possible: one either abstains or kills. The US administration is caught in a legal dilemma, whence its uncomfortable silence.

AS: But doesn’t the drones’ precision allow for better targeting?

GC: The law of armed combat requires belligerents to only directly target combattants, not civilians. Defenders of drones argue that their “constant vigilance” allows for a more precise distinction. Except that, when ground troops are replaced by drones, there is no combat any longer. Without combat, how can you tell the difference, on a screen, between the silhouette of a non-combatant and that of a combatant? You can’t. You can no longer establish it for certain, only suspect it. In fact, the majority of US strikes have hit individuals whose exact identities are unknown. Profiles are established by crosschecking travel schedules and phone records. That’s the “pattern of life analysis” method: your lifestyle tells us that there is, say, a 90 % chance of your being a hostile militant, therefore we have the right to kill you. But this is a dangerous slippage between the category of combatants to that very flexible category of presumed militants. This targeting technique implies the erosion of the principle of distinction, the cornerstone of international law.

AS: Is that the only danger?

GC: One of the main arguments of politicians is the preservation of national lives: evens soldiers will no longer die! But, when military lives are out of the reach of the enemy, what kinds of targets will retaliation shift to? Civilian targets. Amateur drone attacks are a realistic possibility.

Democratic control is also an issue. Kant says that the decision to go to war should be made by the citizens. Because they are the instruments of war, since they will pay the price, they will make circumspect decisions and limit the recourse to armed force. That’s the (very optimistic) theory of democratic pacifism. But you see how the drone disturbs this pretty schema. When an agent can externalize the costs of his decision, he tends to take decisions lightly. This is the perverse effect of “moral hazard”. The theory of democratic pacifism then becomes one of democratic militarism. The drone appears in this sense like a remedy for the internal political contestations of imperial wars. This is clearly the agenda that US strategists who advocated increasing the use of these weapons had in mind after the failures in Vietnam.

AS: The infatuation with this weapon recalls video games…

GC: There is indeed a whole discourse critiquing the “Playstation mentality” of the drone operators, but to me this is a cliché; I am trying to sharpen the analysis. Often, when someone raises this point, they add: “They don’t realise that they are killing”. It’s clear that they know that they are killing.The question is rather: what is the knowledge they base their knowledge of the act of killing on? How does this technique produce a specific form of experience of homicide? It acts like a “moral shock absorber”: you see just enough to kill, but not everything: no face, no eyes. Above all, one never sees oneself in the eyes of the other. It is a dislocated, one-sided experience. The operators are able to partition things off; they kill during the day and go back home at night. War becomes a telecommuting job for office workers, far from the images of Top Gun. It’s not surprising for that matter that the first complaints about drones were made by Air Force pilots: they contested their work being deskilled, but were also fighting to keep their virile prestige.

AS: Speaking of virility, the technical names given to drones are ironic, one might say…

GC: The names are revealing. Predator. Reaper. These are beasts of prey. There’s also a T-shirt in praise of the Predator that reads: “You can run… but you’ll only die tired!”. In English, a drone is called an “unmanned vehicle”, which literally means without a pilot on board, but one could also interpret it as “devirilized”. It is indeed comical that one category of drones was dubbed MALE, for Medium Altitude Long Endurance… A promising label for sure, but will that be enough to gain them acceptance?

Original Article: La guerre devient un télétravail pour employés de bureau

(Libération.fr, May 21, 2013)

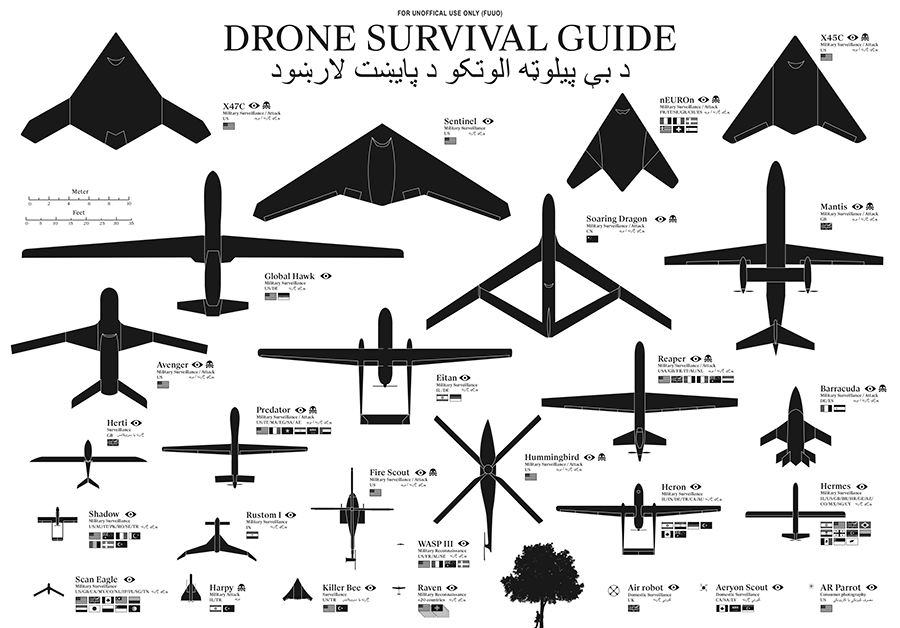

The Drone Survival Guide is a poster and online infographic that uses proportionally sized silhouettes of the most common UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles). Designed by Ruben Pater, a self-employed artist/graphic designer from the Netherlands, the poster is available for download as a PDF.