Forough Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black stands tall, somewhere between moving images and words, sound and music, cinema and poetry, documentary and experimental film; between Realism, Surrealism and Magical Realism, while being none in particular. The work is a mere twenty-minute strip of film, fragments of a special type of precarious existence and love by none other than arguably the most significant Iranian intellectual of the twentieth century, someone whose standing among Persian-speaking people in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and those scattered in diasporas around the world is revived with every new generation. Forough, who single-handedly represents the rebellious spirit of 1960s Iran, is often a surprising discovery for young people, since her audacious and provocative legacy consistently evades canonisation by the Iranian state or academia.

When Persians utter the name Forough, as she is often referred to, rarely is there a need for a last name. It’s as if she is everyone’s sister, lover, or close friend. As singular as her persona is, her film, The House Is Black is her only work of visual art. How did this film emerge amid her successful poetry career in the 1960s? This simple question has lingered as the film has periodically resurfaced, each time gaining importance over its previous appearance, adding layers of relevance and historiography to its significance at the time of its release. Not only was The House Is Black included in 2017’s documenta 14 Athens iteration, but a restored print version was featured in the 2019 edition of the International Venice Film Festival, 56 years after receiving the award in 1963 for the best documentary at Oberhausen Film Festival in Germany.1

The only other modern Iranian artwork that had gained international acclaim before The House Is Black is Sadegh Hedayat’s novel The Blind Owl. Like much of Farrokhzad’s work, The Blind Owl was so densely packed with transgressive imagery that when it was first published in India in 1936, it had to bear a cover note stating “Not For Sale or Distribution in Iran.” Hailed as a masterpiece by Andre Breton and Henry Miller, it was eventually celebrated as high-quality literature once published in Iran in 1942 as part of the rising socialist and secular waves against the country’s traditional and religious character. The Blind Owl is a temporally disorienting tale about the struggles of a pen box painter coming to terms with many social forces personified by the women around him.2

If Hedayat’s The Blind Owl describes, in words, how a seemingly incurable psychological blight decays a man’s sense of living in time, Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black depicts the visual unbearability of leprosy in close-up black-and-white moving images, an allegory for the painful and uncertain transformations of an otherwise vibrant society held back by underdevelopment and religion. Beyond the appearance of leprosy as a real illness, perhaps The House Is Black attempts to discover the secrets of the same social and physiological maladies Hedayat previously depicts in The Blind Owl, but strides forward by providing them with both rational and poetic antidotes.

Since the film’s release in 1962, many scholars and critics have addressed The House Is Black from a wide variety of disciplines inside and outside of Iran. However, what necessitates this text is the fact that not only does Farrokhzad remain a new and unfamiliar face in global contemporary art, but that previous texts on the film, having come from non-art disciplines, lack both aesthetic analysis and theoretical treatment of their subject. This text attempts to address both of these shortcomings and unfolds this marvel of a film in the context of contemporary art. Many marginal and seemingly unrelated histories and anecdotes, including biographical, social and political considerations must be brought to light if we are to unlock the secrets of the film’s emergence in Iran of the 1960s. As the Iranian Studies scholar Hamid Dabashi contends, The House Is Black is the ‘missing link’ between Farrokhzad’s earlier poetry and what she published after the film and the film is misunderstood without her poetry. This text goes further and suggests that appreciating The House Is Black is nearly impossible without first building a dynamic model of the rapidly moving personal, social and cultural contexts from which both Farrokhzad’s poetry and art emerge. These rapid movements are no different from what culminated a decade and half after Farrokhzad’s death in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Luckily before then, Farrokhzad had left Iran, and unlike the women of her generation, she never had to witness how Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution turned the clock back on social emancipation, which was the precondition for her work. She never had to see that the uncertainties which she had foreshadowed in her art literally turned the country into a ‘black house’ again.

This essay rather implicitly puts upfront the notion of recurring time. This back and forthness, rotation or alternation is made sensable in the film. It is also recognisable not only in Farrokhzad’s poetry but also in modern Iranian politics, stretching from the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty marked with modernism and secularism and the country’s descent into political medievalism as a result of the Islamic Revolution. The essay suggests that The House Is Black is a temporal nexus that reroutes the poetic possibilities of the everyday and language to moving pictures and sound. It validates how personal and social life, poetry, and film are similarly grounded in the probability of recursion via the film’s propensity to technologies of acceptance; particularly memory, remembrance and commemoration.

Farrokhzad was born in 1934 in Tehran, around the same time Hedayat was busy authoring The Blind Owl. She was raised in a military family in the Iran of Reza Shah, himself an officer turned benevolent despot/king, consciously self-styled after Turkey’s moderniser Kemal Ataturk.3 With Islam both politically and culturally restrained by the new king’s secular reforms, for the first time the city and the social world had turned into an open space for women. As a young girl, Farrokhzad witnessed the ban on Islamic headwear for women. Officially implemented in 1938, the law was praised by urban educated Iranians, but detested by the clergy and the illiterate majority who were still under their religious and cultural influence.

In 1951 at age 16, Farrokhzad married Parviz Shapour, who later achieved national fame as a satirist and worked closely with Ahmad Shamlou, an older, distinguished poet and nationally celebrated interlocutor of Farrokhzad.4 The couple moved to the southern city of Ahvaz, but the marriage didn’t last long. After four years, Farrokhzad was back in Tehran, working as a typist in the studio of Ebrahim Golestan, an aspiring Iranian filmmaker. Golestan had obtained a contract with the newly-established National Iranian Oil Company to make six documentaries about various operations of the industry. Golestan Film Unit, as it was called, was about to become a place where young filmmakers were trained and provided with opportunities to get involved in independent film productions. As a published poet, Farrokhzad quickly mastered the job, finding herself behind editing machines, cutting and collaging some of the studio’s documentaries.

While working at Golestan studio, Farrokhzad began a tumultuous sexual affair with her boss that lasted until her death in 1967. Her public affair with a married man has been the source of many rumors and judgements against her. The older generation of Iranian intelligentsia insinuates that Golestan heavily influenced Farrokhzad not just in the making of the film but perhaps even in her later poetry; some critics going so far as explaining their relationship as that between a quiet pond and a rock. According to critic Sadr-ed Din Elahi, Farrokhzad was a “motionless feminine pond with no wave or mobility” and that Golestan “fell into that water like a luminous stone and replaced the deadly calm and quiet with lively stirring and motion.”5 The truth is that Farrokhzad was an exceptional woman, not just because she was Golestan’s lover or because she occupied the role of a rare female intellectual in a scene dominated by men. Not since Táhirih Ghoratolain, the mid-nineteenth century Babi poet and political agitator who removed her hijab in a public space, had Iran experienced a woman so readily challenging norms in both art and life. Far from being a quiet pond, Farrokhzad is the first Iranian woman who wrote explicit poems about eroticism, sex, and the female mind.6

In a profoundly different political environment than the one in which she grew up, Farrokhzad’s adulthood coincided with an Iran caught between the 1953 coup against Mossadegh and the Shah’s own top-down reforms in 1962, which was a return to radical secularism and a fresh attempt at driving religion out of public space. The White Revolution further liberated women by giving them the right to vote as well as the freedom to divorce or travel abroad without consent from their husbands. The Shah’s extensive reforms stood in contrast to the Marxist Revolution, always marked by the color red, and the Royal family’s Islamist opponents, who were often identified by the royalist press with the color black. In the midst of this debilitating political vacuum and blossoming economic progress, Iran suffered as a repressed country at the same time that it doubled and tripled its annual income in the oil boom. However, not unlike the case of American avant-garde during the McCarthy era, art and literature were the only spaces in which freedom of expression was quietly tolerated. In the post-coup intellectual atmosphere, the cost of being a political artist was much lower than actually doing politics. The country’s conservative cultural establishment was nevertheless in charge of the official development of art and literature at universities and cultural institutions, but the young modernists in literature, visual arts, theatre and cinema, including Farrokhzad, were gaining ground on the street.7 In a society where only a fraction of high-school graduates could enter university due to limited capacity, involvement in arts and letters was one way of keeping one’s head above the social-capital waters.8

For better or worse, this literary and artistic scene was where politics were openly discussed. In a small world of writers and artists, it was agreed and soon assumed that Iranian modern art and literature, as they would say it at that time, was ‘committed’ to social causes. Although Farrokhzad found her voice in such a context, her complex worldview, materialized in her poetry, could not always fit with this politicized ideal of art’s function and she often found herself at odds with the intellectual scene. For her, being an artist in the 1960s meant witnessing a rapid urbanisation that paradoxically offered an expansive field ripe for intellectual growth to anyone with genuinely interesting ideas. This opening was caused both by the acceleration of government spending on art and culture as well as the development of a successful national culture industry of magazines, newspapers, film and television productions. In this period, which lasted until the 1979 revolution, not a month passed in which intellectuals like Farrokhzad were not publishing poems or other texts in high-circulation magazines and newspapers.

Before making a film as an artist, Farrokhzad was a poet. Her career commenced from adolescence, with the lyrical poems that she wrote from a female perspective. She eventually dropped the romantic sentimentalism of her youth together with her adherence to Persian classic poetry structures. She emerged as a modern master poet equal to her male contemporaries who had revolutionised poetry in Iran after many hundreds of years of formal and conceptual stagnation, perhaps even surpassing them in evolving Persian poetry and thus the language. Farrokhzad’s published poems in her magnum opus Rebirth are works occupying their rightful place in the pantheon of Persian literature. Her frank and unbroken lines are timeless documents of a new Iranian worldview materialised through the voice and lives of their subjects, be they her own sexualised body and its erotic relationships with others, or the lives of ordinary urban dwellers in their quotidian banality. Farrokhzad holds a unique ability to express complex ideas and emotions in primarily lay vocabulary and syntax. This humble yet direct attitude is what she successfully transports to the visual language she developed for The House Is Black.

The House Is Black was not a sudden accident, nor a creative miracle in Farrokhzad’s career. We can see how her earlier involvements with cinema and theatre, which coincided with her poetic rise, could have placed her on this path. Upon her return from Europe in 1959 to attend workshops on editing and film production, Farrokhzad was given the responsibility at Golestan Film Unit to edit the award-winning short documentary A Fire, shot by Ebrahim Golestan’s brother Shahrokh.9 The film depicts the fires at an Iranian oil well near Ahvaz in 1961, which lasted more than two months until they were extinguished by an American firefighting crew. Two other films produced for the National Film Board of Canada, which also owe a debt to Farrokhzad’s unique editing style, are a short documentary on Iranian courtship customs, and Water and Heat, which portrays the dizzying social and industrial ambient of the southern city of Abadan. These productions document Farrokhzad’s mastery of the fast editing of the footage to sound, and her interplay between different depth of shots to emphasise aspects of the subject – characteristics of her work on The House Is Black. These documentaries, available in fragments online, demonstrate her ability to tell stories without description. In 1961, she coproduced and acted in a never-completed film The Sea, based on a story by Iranian novelist Sadegh Chubak. She produced another film in 1962 for Kayhan, the publisher of Iran’s paper of record about the production of newspapers in Iran. In 1963, Farrokhzad acted for the first time on the theatre stage in the Persian-language production of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author (1922). In 1964, she also participated in producing another Golestan film called Mudbrick and Mirror. In 1966, a year before her death, she travelled to London to further study filmmaking and directing, visiting Pesaro, Italy, to attend a film writing workshop.

The House Is Black originated as another of Golestan Film Unit’s short documentaries; it was commissioned by the Society for Aid to Lepers to publicise their operations and help raise funds. What altered the outcome was that for the first time Golestan chose Farrokhzad to both direct and edit the film. According to film scholar Maryam Ghorbankarimi, the film was conceptualised after a brief research trip in the summer 1962 to the Bãbãdãghi leper colony near Tabriz in northwestern Iran. Without writing a script, developing storyboards or planning shots, Farrokhzad returned in autumn to shoot the film with a crew of five colleagues, including the Unit’s sound engineer.10 Early in their twelve-day operation, Farrokhzad, much like an audiovisual anthropologist, familiarised herself with the people and gained the trust of her protagonists. She also pointed her camera and sound crew to survey the environment, recording interesting materials to be used for the purpose of a careful reconstruction of the world of lepers in her film. According to her assistant cameraman, she kept “looking for key moments to capture which later in the editing process would once again come to life depending on how they were assembled.”11 It was immediately clear that Farrokhzad had invested in the film’s capacity to represent time, not just through pictures but also sounds. Coming from poetry, she was predisposed to think of the immense capacity of sound in the film’s conceptual armature. Obsessed with her subjects and feeling ashamed of abandoning them, Farrokhzad adopted one of the young boys who acted in her film, taking him back to Tehran.

Much of the related discourse on The House Is Black by both Iranian and western scholars revolves around the dialectics between being a ‘humanitarian documentary’ or a realist short film.12 Farrokhzad has also been credited for contributing quite early to the development of the essay film as a genre. These texts interpret the film as an artistic and secular metaphor on mid-century Iran, a society in which resorting to religion and spirituality had failed to provide remedies to physical and social ills. However, the genealogy of The House Is Black in Iranian cinema, as noted by scholar Rosa Holman, must consider its direct connection to other important global modernist practices:

“The fact that Farrokhzad’s film won the Grand Prize at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1963, at a time when German cinema was undergoing its own cultural and formal transformation, is arguably significant. In 1962 a group of filmmakers, among them Alexander Kluge and Edgar Reitz, issued the Oberhausen Manifesto, which declared traditional cinema was ‘dead’ and expressed a desire for a radically new form of German cinema.”13

The House Is Black’s reception in Europe demonstrates that its success was not only a sign for the emergence of “transnational form of cinematic modernism”, but that it placed Farrokhzad as a pioneer in such a movement.

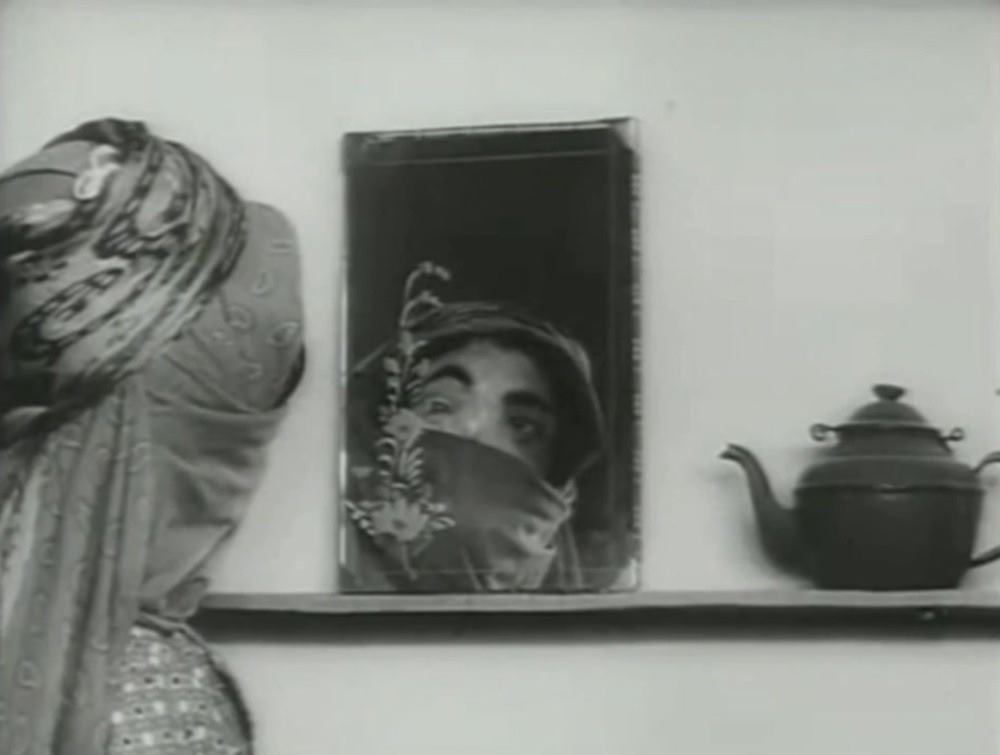

The film opens with a closeup of a woman’s face seen through a mirror with her back to the camera. Her face, particularly her right eye, is severely scarred by leprosy but it is at the same time festooned by the floral pattern etched vertically on the mirror. Farrokhzad’s camera then moves into a classroom packed with young and old students and depicts several boys who while holding the second-grade elementary textbook, read the well-known introductory prayer text in which the god is thanked for giving us “eyes to see the world”. The introductory classroom scene, to which the film returns for its powerful finale, concludes with rows of male students facing the blackboard but staring at the camera while Farrokhzad’s voice recites: “Who is this in hell praising you, lord? Who is this?” The film then cuts to a closeup of the deformed bare feet of one of the male residents, who is using them to dance a rhythm on a rug covered ground. It then slowly traces the dancing man’s body up to his deformed face, showing him sing emotionally charged sounds. Next, the camera surveys many lepers in the colony in closeup, allowing viewers to see the different ways in which the illness has scarred their faces. Later on, in medium shots, we see the colony residents conversing, eating, laughing, resting, even brushing each other’s hair and attending a wedding. Some segments in the film feature Farrokhzad’s voiceover reciting poetry as well as verses from the Bible, apparently as an ode to the colony’s Christian origins.14

An important conceptual element that frames the film is that The House Is Black begins neither with Farrokhzad’s poetry nor her pictures, but with Golestan speaking against a black screen in a rational tone about both the film and the illness. In the film’s documentary segments, Golestan’s voice returns to share scientific knowledge about leprosy, its prognosis and treatment, accompanied with images of patients in the colony’s clinic during operations or while receiving physical therapy. Some scenes are almost as heart-wrenching as the faces, feet and hands accompanied by Farrokhzad’s poetry, which constitute the film’s gorier and more macabre content. Acting as an alibi for a love child the couple never had, the film swings between these two modes of speech without attempting to resolve the contradiction that arises from the hopeful tenor of Golestan and the melancholic tone of Farrokhzad’s recitations. The film’s cyclical structure reveals its finality when the camera returns to the classroom to depict exchanges between students and the teacher about their lesson, which seem to have been staged and have metaphorical connotations for the film. In the concluding exchange, when asked by the teacher to construct and write a sentence including the word ‘house’ on the blackboard, the students write, “the house is black”.

In addition to the contrast between Golestan’s matter-of-fact voice and Forough’s poetic one, another structuring device that grants the film further depth is the interplay between sounds, voices and music, as well as the changing rhythm of moving pictures. The conscious synchronisation of sound and image editing is the true magic of the film. By overemphasizing the ambient sounds and splicing the film accordingly, The House Is Black’s audiovisual materiality is a world-making exercise constituting a convincing bedrock for the dual set of propositions by the film’s male and female narrators.

Regarding the film’s main device, namely the rapport between Farrokhzad’s metaphoric and Golestan’s realist narrations, in his often-quoted text on the film, American critic Jonathan Rosenbaum suggests that Farrokhzad might have meant to produce a “poetic documentary … conjuring up a potent blend of actuality and fiction that makes the two register as coterminous rather than as dialectical.”15 The blending of two distinct voices is not without precedent in Persian poetry, which is often experienced in a ritual called Moshaereh in which two poets engage each other through recitations that overlap in their either formal or metaphysical dimensions. The film can thus be tagged as a cinematic Moshaereh between Golestan and Farrokhzad; their voices as distinct as the two types of modern humanism: scientific and rational versus subjective and poetic. This sparringly contrasts with human traditions lived by the colony’s residence, especially their reliance on religion and prayer as a way of coping with their condition. Farrokhzad is able to employ the radicality of Persian modern poetry to tackle leprosy’s physical and metaphysical aspects.

According to Ghorbankarimi, in a 1963 interview with Bernardo Bertolucci in Tehran, Farrokhzad emphasises the metaphoric potentials of the devastation caused by leprosy on the human body to exemplify “a model of the world imprisoned by illnesses difficulties and poverty”,16 the ease with which the film alternates between the reality of leprosy and its poetic potentials constitutes its other cyclical essence. This didactic reading is then contrasted with a movement between the supposed ugliness of individuals portrayed motionless in closeups, and the beauty of them moving and living their lives. It as if to love these people – these strange creatures you have never seen before – the viewer must first dislike them. The Farrokhzad agnosticism of not chosing between hope and despair as the message of the film opens viewers to the consideration of life’s vitality and beauty, even in its most ‘inhuman’ form. In response to a question of whether there were any suicides in the leper colony, Farrokhzad is said to have stated: “Disappointment has no meaning there. The lepers when going to the colony have passed the disappointment stage. They have accepted life as it is. I have seen more people there attached to life and loving to live than anywhere else.”17

Rebirth

My entire verve –

is a dark verse.

It will take you –

to the unending dawn of blooms,

flight and light.

In this verse,

I heaved you a sigh, sigh.

In this verse,

I tied you to trees,

water and flames.

Life perhaps,

is that long, shady road,

where every day, a woman wanders –

with her basket of fruits.

Life perhaps, is that rope;

the one that a man would hang himself with –

in a gray, rainy day –

from a thick branch.

Life perhaps,

is those brief smokes,

in the lazy, idle times –

stolen from two making-loves.

Life perhaps,

is that still instant,

when my eyes sink into –

the reflection of your sight.

Life perhaps,

is its sheltering sense;

I will merge it – with the flood of moonlight –

and the frozen abode of night.

In my little,

lonely room,

my heart is invaded –

by the silent crowd of love.

I am keeping track of my life:

The beautiful decay of a rose, in this antique vase;

the growing plant that you brought,

and those birds in their timber cage.

They are singing every hour,

up to the full depth –

of their view.

Oh …

This is my share.

This is my share.

My share,

is a piece of sky –

and a little shade –

can take it away.

My share,

is a gradual descent –

from some deserted stairs.

It is a sudden landing – in some

forsaken, exiling place.

My share,

is a gloomy march –

in the distant garden of my past.

My share,

is a slow death –

for the advent of a voice.

The voice –

who once said:

“I love your hands”.

I will plant my hands.

I will grow,

I know, I know, I know.

And a lost bird –

will lay lots of eggs –

in my inky palms.

I will pick a pair of twin cherries,

and I will hang them on my ears.

I will take two white oleanders,

And I will put them charily –

on my fingertips.

There is a road,

full of young, vulgar boys.

I used to be their sole muse.

They are still hanging –

with their untidy hair, –

with the same thin legs,

about the same square.

And,

they are still thinking –

of that little girl with a shy beam;

the girl that one day –

faded in the breeze.

There is a congested road that my

heart,

kept it from my childhood

neighborhood.

The journey of a mass in the row of

Time;

And loading this arid line,

with the weight of its shape –

a polished, smooth, even shape –

coming from a place,

just after the village of mirrors.

And it is so –

that someone remains

and some will die.

Did you ever meet a fisher who caught

a pearl –

in the yellow, inert, close-by river?

I know a sad, little fairy.

She is living in a remote ocean.

And she is playing her heart –

into a wooden flute.

A sad little fairy –

who dies every dusk.

She is reborn the day after –

right at the dawn,

from a slight kiss.

The restoration of Forough Farrokhzad’s 1962 masterpiece The House Is Black premiered at Venice Classics 2019 as a joint project by Cineteca di Bologna, Ecran Noir productions and Ebrahim Golestan.

1 Apparently, Farrokhzad was preparing to make a feature film before her death. A 1,000-page script was recently discovered in Iran, outlining her plan to picture the situation of Iranian women. Cahiers du Cinéma, July–August 2019. https://www.cahiersducinema.com/produit/juillet-aout-2019-n757/ (accessed 15 September 2019).

2 Edayat’s story opens: “There are sores which slowly erode the mind in solitude like a kind of canker. It is impossible to convey a just idea of the agony which this disease can inflict. In general, people are apt to relegate such inconceivable sufferings to the category of the incredible. Any mention of them in conversation or in writing is considered in the light of current beliefs, the individual’s personal beliefs in particular, and tends to provoke a smile of incredulity and derision. The reason for this incomprehension is that mankind has not yet discovered a cure for this disease.”

3 Another of Reza Shah’s reforms was mandating families to abandon the older Arabic naming system through which people’s first name followed their father’s first name, and instead to choose a last name for the entire family. To understand the secular origins of Farrokhzad’s personal worldview, we must note that her father chose Farrokhzad, which was the name of a celebrated military man from the year 700, who led Persia’s unsuccessful counterattack against the Arab and Muslim invaders.

4 Parviz Shapour (1924–2000) invented a new short form of satirical writing with poetic and philosophical connotations which Shamlou coined as Caricalamtour by combining the term caricature with the term calameh meaning ‘word’ in Farsi. Two often-quoted examples of this genre by Shapour are: “All the people in the world exercise silence in the same language” and “From the guillotine’s point of view, a human head is a dispensable organ.”

5 See Farzaneh Milani, Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers, I.B. Tauris, New York, 1992, p. 190.

6 Those who still insist on Farrokhzad’s indebtedness to Golestan can consider the intellectual standing of some of her family members and realize she was capable of greatness on her own. Farrokhzad’s older sister Pooran was a writer, translator, literary critic, journalist and researcher who published thirty books, one of the most important of which was the Atlas of Successful Iranian Women. Her younger brother, Fereydoun Farrokhzad, later a 1970s pop singer and national celebrity in Iran, originally studied humanities in Germany and received his PhD in political science from the University of Munich with a dissertation on the influence of Marx and Marxism on the state and church in the Democratic People’s Republic of Germany. Inspired by Farrokhzad’s book Another Birth, Fereydoun published his own collection of poems in German called Another Season in 1964.

7 The broader picture of the place and significance of intellectuals in the sociopolitical life of Iran during this era is brilliantly explained by Mehrzad Boroujerdi. See Mehrzad Boroujerdi, Iranian Intellectuals and the West: The Tormented Triumph of Nativism, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 1996, pp. 42–51.

8 Ibid.

9 A Fire won both the Golden Mercury and Golden Lion Awards at the 1961 Venice Film Festival.

10 Maryam Ghorbankarimi, The House Is Black, A Timeless Visual Essay”, in Forough Farrokhzad, Poet of Modern Iran: Iconic Woman and Feminine Pioneer of New Persian Poetry, I.B. Tauris, New York, 2010, pp. 137–148.

11 Ibid.

12 Hamid Dabashi, Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema, Mage, New York, 2007, pp. 39–70.

13 Rosa Holman, Recovering Voice, Reclaiming Authority, Ph.D. diss., University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2014. MLA International Bibliography.

14 One of the hallmarks of Jesus Christ’s life was his compassionate treatment and healing of many lepers (Luke 1: 1–4). This has inspired the Church and Christians over the centuries to have a special outlook on the illness.