“The maturity of the late works of significant artists does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are, for the most part, not round, but furrowed, even ravaged. Devoid of sweetness, bitter and spiny, they do not surrender themselves to mere delectation.” – Theodor Adorno, “Late Style in Beethoven”

The effects of senescence on accomplished artists is a familiar enough phenomenon. In addition to Beethoven, Leon Golub quotes from the same Adorno essay on his own late work, that “[i]n the history of art late works are the catastrophes,” and we see other works of the kind from Titian, Goya, Picasso, Jasper Johns, Godard. Coppola’s Megalopolis is a new work within this canon, a cracked, quixotic, difficult paean to the dream of utopia in the face of one’s own mortality. But whatever the specific and considerable interest there is in dying old men ceding their immense egos to the infinite void of death, we already know what it is. They’ve reached their end, but my concern is with what is left in their wake for those who are not yet old.

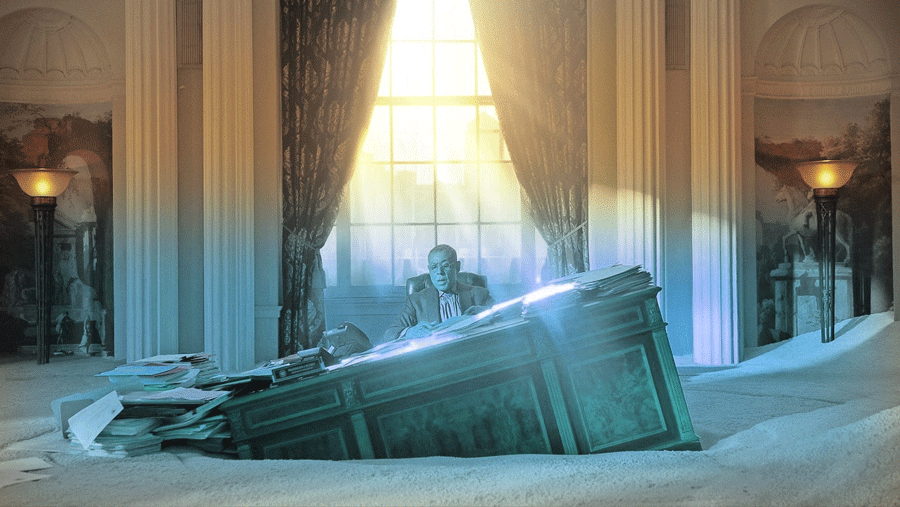

Part of the charm of Megalopolis is precisely its excess and indulgence in a cinematic climate that has written out the passion project, or even the basic notion of artistic passion as something distinct from professionalized commerce, which is why Coppola had to sell his wineries to borrow hundreds of millions of dollars to finance a $120 million self-production. It’s an extreme example, but an instructive one. The director of The Godfather bought his first winery with the proceeds from that film and managed to build a commercial empire, which is the only reason he has the fiscal leverage to make a truly late work. This is already worrisome, but what chance is there for a 2020s auteur to make a crossover hit that will give them the fame and fortune that they can joyously squander in their old age? The arts as a whole are failing to bear new fruits in the perpetual drought of social decline, profiteering, populism, functional illiteracy, everything else, etc., etc. We find ourselves in a state of infertile “late art” that mirrors the gnarled heart of the artist’s endgame.

As a critic I very seldom come across new artworks that produce any real feeling of novelty, and when I do it’s usually by a late career artist in at least their seventies. In part this surely is because they grew and flourished as younger artists in more nurturing conditions, but there’s no point in bemoaning our cultural decay because we’re stuck in it. Any reform in the visual arts would have to be preceded by a drain on the glut of money in the art market and an increase in earnest art appreciation, but a market crash, no matter how deserved, is liable to be more catastrophic than salutary in the short and long term. Without any hope for material change the only sensible attitude is an immense negativity, but this contains a silver lining: art is not politics, so social hopelessness is not definitively artistic nihilism.

The artist has no need to pander to their public because their existential responsibility is to the production of their work. The artist can yield to the alienating embrace of negation as a motivating force without sacrificing their effectiveness as art. They may sacrifice their market appeal, but the market’s wiles are little more than the temptations of decadence and decay. It is, of course, no mean task to persevere in opposition to one’s nominal industry, but when the system makes authenticity impossible it becomes necessary to militate against it to reclaim a shred of truth in a sea of duplicity. What I’m advocating, then, is for young artists to discover their lateness before their time to match the lateness of our era. But what is this lateness?

Rather than the distilled culmination of an artist’s individual genius, it is the subsumption of the artist into the art, the decline of the subject’s force as the art object carries on into the unknown, which is to say that the artist concedes their preeminence to that of death. Art’s form surpasses the artist’s control over it, which has never been more than a convenient illusion. Now that art no longer produces new masters and the world we inhabit is itself a catastrophe, it has become necessary to preempt the nearness of death in art from the beginning, to work from the first as an agent of catastrophe. Otherwise we are hopeless.