For a larger version of the accompanying graphic, please click here.

The arts, thanks in significant part to the Serfdom Patent (mobility) and the Toleration Patent (pluralism; both 1781 in CE region), moved away from work based on commissions. Commissions meant expressing the world of others. Art moved vehemently towards the expression of the self. Serf was forced to modulate to self. Thus, from the 19th century onwards, we also distinguish more precisely between free art and applied art.

I use “free” instead of “fine”. At first, that’s how fine arts is called in my native (Slovak) language (“voľné umenia”), but also because “fine” (coming from etymological root of fīnis = the end) means definite, delicate, high / noble… and contemporary arts is anything⎯but nothing like that in general.

Free art is unconditioned while applied art is conditioned. Free art’s expression of the “I” is part of the complexity of individuation. Individuation was the construction of “one”⎯certainly the Modernist ideal. But “one” in understanding of Modernists was “we” (which leads us closer to applied art) or even “everybody”; in the absolute contrast to what I call the Second Contemporary⎯where “one” is “I” and “anybody”.

On this schematic basis, I test how useful Contemporary Art can be for us⎯in looking at the parameters and mechanisms of identity today.

Even used by Giorgio Vasari already in 1568, the term Contemporary Art (in today’s sense) was unofficially coined by the English painter, art dealer, critic and one of the first curators Roger Fry. This was how he hand-labelled crates with the most recent French paintings of his era⎯in his London warehouse in 1903. Style of that art had NOT YET been classified. In his case, it was a spontaneous, improvised, provisional (pre-phenomenological) phrase associated with time⎯and NOT yet a term / an ism. He himself later (1906) named that trend “Post-Impressionism”. It should be noted that as early as 1870 Impressionism had been named “Post-Modern” painting⎯by his older colleague John Watkins Chapman. Fry’s Post-Impressionism was an economic-pragmatic (generalising) umbrella for many yet unfiled styles.

In his biography, his close fellow Virginia Woolf (1940) put the situation this way: “In any case, he must have realized that there was another force at work in Contemporary Art which appealed much more to his own instincts and satisfied both intellect and sensibility. This force, which he later named Post-Impressionism, gave him and many others the freedom to become themselves.”

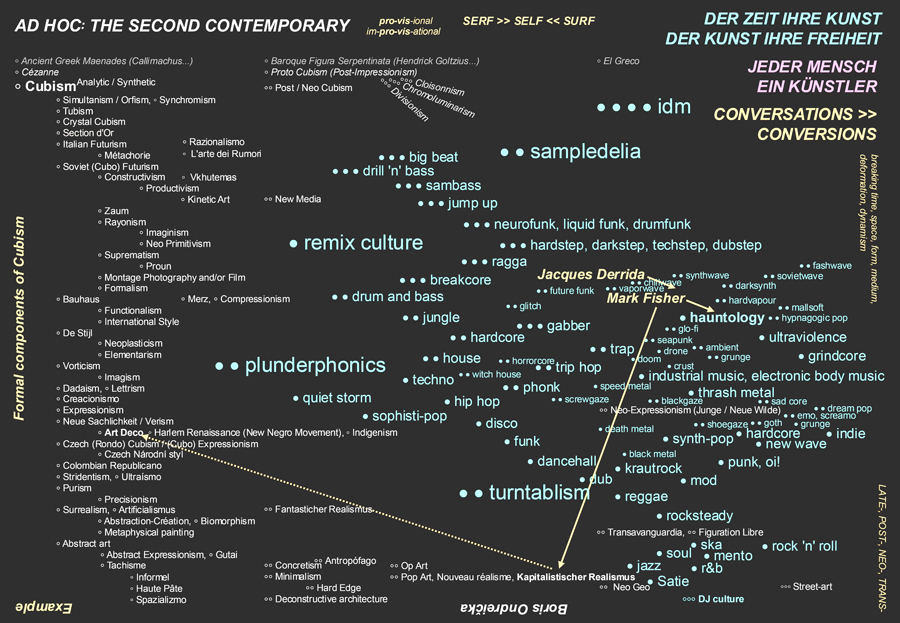

Fry, along with Alfred H. Barr, Clive Bell, and Clement Greenberg, were the first to define avant-garde Modernism NOT as a continuum, but as an autonomous practice vis-à-vis the pioneering styles of the (late) 19th century. Interestingly, Hans Arp and El Lissitzky’s Kunstismen publication recorded 16 dominant isms in 1924, and flow-charts context of the influence of Alfred H. Barr in 1936 already dozens more. We can register a massive fragmentation or fractalization of art of that period. I put this fragmentation / fractalization (as demonstrated by the example of the Cubism diagram attached) in direct connection to fragmentation / fractalization of an idea and realization of self.

I expose Cubism as the most influential method of art of the last two centuries: breaking the form, triumph over elusiveness of time and space, deformity as a tactic of expression of dynamics⎯heading towards (better?) future. That convenes with the aspect of the Contemporary very much.

Fry (manifesting himself as an individualist anarchist) co-founded one of the very first institutions of contemporary art, The Contemporary Art Society, already in 1910. It served as an advisory service for private collectors, while at the same time pooling private capital to purchase the most contemporary art. It then donated this to leading museums. In this way it has been instrumental in the accelerated spread, appreciation and adoption of new trends. Donations were speculative shifts of conversations to conversions of subjective to objective, private to public, value to price.

Subsequently, a number of institutions began to emerge with the attribution of contemporary. For example, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston, which opened as the Boston Museum of Modern Art in 1936, changed its name to Contemporary in 1939.

Speaking about the contemporary and its pioneering institutions⎯being in Zagreb, in its Museum of Contemporary Art; I just must quote Peter Osborne’s wrong nostalgic mystification from his very popular Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (2014) who mentions that “the distinction between modern and contemporary was first stabilized after 1945 not in Western art history, but in Eastern Europe, as part of the Soviet reaction against the categories of modernity and modernism. For Georg Lukács, for example, in the 1950s, socialist realism was ‘contemporary realism’, since the actuality of socialism defined the historical present. The City Gallery of Contemporary Art (Galerija suvremene umjetnosti [author’s note]) in Zagreb, founded in 1954, was one of the very few art institutions to use the term before the 1960s. In Eastern Europe, ‘modernity’ was considered an ideological misrepresentation of the historical time of capitalism, covering over its internally antagonistic class forms of historical temporality and representation.”

The awareness of Contemporary’s powerful momentum (and precariously rapid erosion of selected isms) also altered the procedural typology of its institutions. They began to concentrate on the production of temporary exhibitions as opposed to collecting activities. Thus, against Modernist sustainability dream, a preference for possibility (of the ambiguous outcome of the Contemporary) became apparent. The investment in temporariness also expressed a disbelief in the long but strong current confidence.

Encounters of the overwhelming multiplicity of the individual in art caused certain averaged neutrality, and so spaces for the temporary presentation of unpredictable art were meant to be sterile. The first white cube was the Vienna Secession building (1898). Secession means separation. Detachment has since become one of the most fundamental internal features of avant-gardes.

Fry’s Contemporary Art (I call it the First) was the roof of STILL lack of categorization, which it longed to fulfil ismically. It was the absence that bothered. Ismic ambition was the dynamic of creating a more unifying “we” to the point of quasi-post-catholic entitlement to everything. “We” was certainly some panic reaction to involuntary alteration from serf to self, so consequently being radically alienated, losing the security of serfdom. But the ultimately dominating personal authorial individualism and the internal nature of the Modern in its pull to be a priori new and preferably first, original; permanently disrupted the unity. Secession was NOT only a separation from the old, but of a single person (“I”) from its own generational group (“we”) as well. Thus, the history of the Contemporary, rather than non-linear relay-races of parallel constructive isms, must be read as a disparate number of always destructive (transgressive and subversive) acts of single individuals. It is a history of demands for unbridled freedom of what can be art which we can synonymize with ontological self-determination at large⎯all the way from Gods of Elsa Freytag-Loringhoven (1915) to Joseph Beuys’s 1971 legislative declaration “Jeder Mensch ein Künstler.” Anything declared to be art by the first person is art; and from that point on, no second person has any tools to contradict that it is NOT. But more than a similar posture was formulated much earlier⎯by John Dewey in 1932.

Looking at it from today’s perspective, the Postmodern (or Late-modern or in other words Neo- or Trans-avant-garde, or Late capitalism; as predicted by Werner Sombart already in 1919, including Russian perestroika) was then NOT an effort to resuscitate the Modern, but only a rainbow firework display of its agony ending with the iconic 1989.

The godfather of socialism, an entrepreneur Henri de Saint-Simon (in a dialogue with banker Benjamin Olinde Rodrigues) introduced the militant term avant-garde in 1824 according to his belief that art is the fastest way to influence any social change. Avant-garde means the array of inexperienced, unarmed, barefoot infantry (which comes from the word “child”). From the experience of today, we can consider the unconscious self-image of the infantile avant-garde as a self-annihilating struggle between a constructive “we” and a destructive “I”, doomed to extinction in advance. Presence of self-identification with infantry >> child, suggests to us that the avant-garde carried a certain congenital Peter-Pan-syndrome of unwillingness to grow up, to remain perpetually adolescent⎯a continual becoming and NOT yet being. It is an effective strategy which allows one to ask (parents, society…) for protection, support, tolerance with disobedience… Right because of this tolerance, art is allowed to be the fastest discipline indeed.

Emblematic 1989 was the end of the isms. I was 20 by then. “NO isms” means no categorization, NO classification, NO equality, NO unity. We can say that this is the end of the “we” in art. We can speculate if this is NOT also the end of “left” in art as well. The term Contemporary reappears after 1989, but no longer as any safety cocoon where new isms are born, but quite the opposite. It is an exclusive incubator of “I”. Absence here is NOT a place of fulfilment, but an attempt to allow landless freedom. It is that universal neutrality (void) of the “white cube” mentioned. And void is a synonym of both chaos and freedom. The Second Contemporary is an autonomous practice vis-à-vis Modernism. For the return of the Contemporary I call it the Second Contemporary. If Fry’s the First Contemporary was NOT classified YET, the Second Contemporary is NOT classified ANYMORE. What they both still have in common is complete improvisation in a totally provisional situation. Im-pro-visation and pro-vision share a common core⎯”pro-vis” presupposes imagination and so the effort to break out of time away. It is the rigorous acquisition of a barefoot cruel freedom which (logically) excludes any certainty. It is no longer liquid, but gaseous. That diffusion (which spreads out in all directions and thus has no tenacious shape) rejects responsibility and so rejects governance, because to be free means NOT only to be NOT governed by others but also to NOT govern by yourself. If it refuses to govern, it ceases to claim many societal roles and recognitions. When we say gas, we may also think of the personal psyche (anima, soul) and leaking super-personal pneuma (spirit)⎯the gnostic ideal of self-destructive dematerialization as a process of becoming. Dematerialization is one of the leading métarécits of the art of the 20th century. When we say gas⎯full gas, we speak about extreme speed. The Second Contemporary is an infinite resignation on big (big goals, big names… and soon also big prices). But that has nothing to do with degrowth, because “small is more.”

Counter-intuitively the Second Contemporary did NOT come as a movement. It had no manifesto, only an embryonic motivation of a kind of subconscious eureka without the indication of an increased heartbeat. It was NOT accompanied by either enthusiasm or sarcastic decadence. It was merely a change of movement totally unrecorded in its inception. Something uncommunicated that we only noticed was already here. It still doesn’t bother, and so there is no stronger inclination to investigate, much less name it. To not name means deliberation from formal language and definiteness. “To not name” (untitled) is important to many artists. In 1989, there was a lack of provocative foreshadowing because there was NOT even a symptom outwardly revealing some hidden deeper tension. For there was no longer any inner sickness. Contrariwise⎯burn-out and the subsequent expiration of Modernism (the isms themselves) signified the unburdening, the cure against hope. Loss of hope thus dissolved the desire for domination.

When I say that there was no longer any inner sickness, I am also thinking of Antonio Gramsci’s famous prophetic statement of 1930: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Today, his “crisi” and so the “phenomeni morbosi” no longer work at all. That “the old is dying and the new cannot be born” is valid, but the Second Contemporary NOT only does NOT mind it but welcomes it. If no “new” can be born, it means that everything remains the property of “us” alone, in Stirnerian (1844) sense. And so, if we agree that the Second Contemporary yet crisis is and is major and unchangeable (it is); then we can consider it (statistically) as “normal”. This negates the notion of crisis. So, we have rather (rationally or subconsciously) learned to live in it, or at least to circumvent it, to ignore it. So, we emotionally and aesthetically neutralized it. It was Modernism that was the crisis and fatal morbidity (its quasi-feudal appetites…). So, Gramsci’s interregnum or Schumpeter’s intermezzo was (actually) 200 years long. That waiting died.

When I mention gas, I think of naive Modernism’s burnt-out by the feverishness of the avant-gardes. So, it also burned away all the inner sickness, which was also hope mentioned. The Second Contemporary is hopeless, and that means curing ourselves also of the eschatologically messianic necro of Modernism’s entitlement to “everything”. The Second Contemporary is NOT “everything”, but “anything”. Hopelessness means lightness. Lightness means mobility. If there are no internal diseases, then there are no symptoms to respond to either. And so, the Second Contemporary is no longer referential, but merely (non-manifestatively) interferential.

If I mention provisionality, improvisation and the absence of categorization, the only way to discern, to navigate the hyper-pluralism (or even solipsistic egotism) of the Second Contemporary might be ad hoc. Pluralism (after the Toleration Patent) means necessary secularization. In an apparent paradox, only secularization allows free realization of personal spiritualities. Ad hoc means “for this purpose”, “what is available”, “from case to case”, “hypothetically” … “we’ll see”. Ad hoc is always only finite unit (in a kind of relay of inauthentic ephemeralities). And so, it requires constant attention as a permanently active (highly empirical and experimental) mode of orientation and organization. There is no internal memory anymore, but the cognitive loop of external reminding⎯hyper-reactive on over-impulsed networked nature of everything.

If we inflect adaptive, integrative, flexible, creative, spontaneous… ad hoc, we can talk about adhocism (Warren G. Bennis & Philip E. Slater, 1968; Alvin E. Toffler, 1970; Charles Jencks & Nathan Silver, 1972) and adhocracy. Adhocracy is an organic, maximally adaptive, mobile, promiscuous and minimally formal managerial structure based on a decentralized, distributed network of independent expert contractors as a possible opposition to (state) bureaucracy.

If individuation means dis-division (which sounds like the Modernist intention), and that has failed; then identity today must be seen in reverse, as dividuation⎯secession. Division, dispersion, secession was precisely the very counterintuitive nature of the avant-gardes, which gradually shattered from within into grains of dust, gas, fog of the Second Contemporary. Dividuation (Gilles Deleuze, 1986) sees the “I” diasporically scattered piecemeal in the sense of mycorrhizal dispersal. No roots, just cosmic wireless nets of mutually compatible and thus attracting fragments, migrating “material sympathy”⎯as Jane Bennett (2014) might put it. Speaking about disintegration, Fernando Zalamea (2011) describes the process of decay as an expression of a profound continuity in nature through which “creativity expands without brake”.

So, how can the Second Contemporary, being with us for 35 years already, still be contemporary? It is because contemporary (con-tempus = “with-time”) does NOT mean “being with time”, but “going with time”. That’s an expression of its gigantic mobility and adaptability⎯as basal qualities of postapocalyptic survival.

So, if we identify the development of art since the beginning of the Long 19th century (Modernism as a history of individuation), and this process has failed; we will understand it NOT only as an unsuccessful project, but as a wrong concept per se. We will read the origins of the Second Contemporary NOT as a history of con-vergence but as a saga of di-vergences. Then, the crisis of identity means a mistaken manipulation with wrong subject / the subject which has roots in nobility’s exteriorization of its existential responsibility for serfs on their own shoulders. We are NOT dealing with identitās (which means “sameness”) but diversitās.

Let’s mention, that the term person comes from Greek πρόσωπον (prósōpon, which means “face; appearance; mask used in ancient theatre to denote a character or a social role”, mask⎯strong component of Cubism, Compressionism, Expressionism and social networks).

∙ So, what if the Second Contemporary provides us with an unembellished entry into reality; or (actually) anticipates it (art as the fastest of all disciplines)? ∙ What if the Second Contemporary is the best laboratory expert of dividuation? ∙ What if so-called identities (and with that the Western ethos itself) are already only something ◦ non-ismic, non-canonical, apocryphal, marginal; ◦ timeless, micro-eternal, endless series of ephemeralities; ◦ amorphous, abstract, inconsistent / contradictory, polemic (like combustion engine), transparent (so that’s why invisible; in words of Thomas Metzinger, 2003, dark and scary), immeasurable; ◦ purely aesthetic and symbolic; ◦ dividual-istic / superjective, orphan, alien, multi-cultural / syncretic; ◦ apolitical, amoral and immoral, unfair; ◦ eclectic; ◦ anarchic precariate (which is necessarily predatory); ◦ generationless, ageless, classless and genderless (as merged by Erik Olin Wright, 2012); ◦ meta-intuitive; ◦ hyper-adaptable, mobile / promiscuous // prostituting; ◦ hopeless; ◦ infinitely resigning / cynical (which means ascetic in one and hedonistic in the other at the same time); ◦ chimerically free (which means absent, totally uncertain and cruel, disparate aerosol dispersed ad hoc; after Otto Rank, 1907, commented sublimation of internal desires into socially acceptable behaviour) and ◦ fast without any restraint? ∙ What if hyperstitious (Nick Land and Mark Fisher, 1995) illusion of the Second Contemporary is (in words of Laboria Cuboniks, 2015) a DIY-politics of pure alienation entirely? ∙ What if even capitalism itself is already so fragmented that it has lost any consistence of ism, so Schumpeter’s 1942 “creative destruction which gives the space for new” is NOT needed anymore, because the infection of arrogant hope was burned-out already in 1980s and just left the most fertile composts all around? ∙ What if consistency (another mode of failed individuation, the fetish of philosophical method) is just an obsolete / functionless prototype of Modernity? ∙ What if the journey is the goal indeed? ∙ What if we do NOT question (with Fredric Jameson, 2003) what will be after the mirage of the end of history anymore, because the end is here already, but it is an infinite interval of decay⎯Hakim-Bey’s (1990) relay-race of temporary autonomous festivities, rejection of one big revolution but hailing of many small revolts; Jacob Taubes’s (1947) history which is constructed only by decisive and dividing acts; or the concept of progress made by a relatively small group of highly organized individuals (secret, hermetic esoteric conspirators) in the sense of Auguste Blanqui (1872)? ∙ What if that decay already went through a process of distillation, so turned to an alcohol we use for disinfection and suppressing social hardship drinking as hell? ∙ Yes, what if identity now (which I used to call identific[ ]tion) is only an abstract field of associations and expressions which does NOT keep any formally sustainable structure anymore? ∙ What if an abstraction is the most proper method of contemporary realism?

So, even if we forget any former Modernist hallucinatory answers of revolutionary unification (and philosophical consistency) we don’t have to resign on avant-garde revolts; because (I repeat) the Second Contemporary Art is the fastest of all disciplines anyhow. I somehow feel that the Second Contemporary behaves similarly to raw and cruel nature. It is an ad-hoc quasi-regulation or chaos magic of egoisms based on irrational confidence between other(ness)s.

These days, I feel very much the same as what half-rabbi Jacob Taubes wrote to jurist Carl Schmitt around 1942: “I have no spiritual investment in the world as it is.”⎯but that does NOT mean that “I have no spiritual investment in the world as it should be.”

* Delivered at Identity Crisis Network International Conference, Zagreb, HR, May 23-24, 2025.