It’s well known that when people venture into the far reaches of consciousness, they do so at the peril of their sanity, that is, of their humanity. But the “human scale” or humanistic standard proper to ordinary life and conduct seems misplaced when applied to art. It oversimplifies. If within the last century art conceived as an autonomous activity has come to be invested with unprecedented stature— the nearest thing to a sacramental human activity acknowledged by secular society— it is because one of the tasks art has assumed is making forays into and taking up positions on the frontiers of consciousness (often very dangerous to the artist as a person) and reporting back what’s there. Being a freelance explorer of spiritual dangers, the artist gains a certain license to behave differently from other people… [h]is job is inventing trophies of his experiences— objects and gestures that fascinate and enthral, not merely… edify or entertain. -Susan Sontag[1]

In postmodern, globally-integrated, and nth-dimensionally complex societies, does it still make sense to speak about the artist’s vocation in such terms? The task of this essay is to investigate such a question. The hope is to show how this artistic ambition— subject to certain revisions— ought not to be abandoned, and in fact could prove indispensable to thinking about art in the greater context of modernity.

To test this idea we will need to interrogate its pertinence with respect to the notion of planetary-scale complexity. As will be suggested in what follows, contemporary experience is significantly characterised by the condition of being Nth-dimensionally (NthD) complex,[2] meaning that individuals are implicated within systems, networks, or phenomena whose meaning and extent are not adequately captured by local situatedness. Insofar as we consider it the task of art to be socially and politically relevant, we might conclude that speaking to what is merely immanent to the individual artist’s experience is therefore less than adequate.

We should be wary here to avoid crude attempts to liquidate the local or experiential dimension entirely, not least because art as we know it cannot be understood without recourse to the primacy of experience. Rather than a banal and frankly implausible attempt to deprecate experience and situatedness entirely, our strategy is to transform the local, such that more parochial conceptions of a situated but largely precritical subject are dissolved in favour of something better situated and conceived in terms of continuity rather than absolute discreteness. The claim, by distilling Sontag’s aphorism down to its basic idea, is that art so considered can prove extremely important in giving us tools to navigate the NthD complex on a political level, as well as for the task of individual orientation on the ethical level— matters which are here taken to be intimately linked.

As a final introductory remark, whilst Sontag’s account undoubtedly romanticises the role of the artist, I will unashamedly endorse her ambition in this regard. This essay is certainly an attempt to justify or at least understand art within the scope of a social ontology, but we can achieve such goals without trying to rationalise art such that it is considered a matter of mere functional sufficiency. Moreover, it is a signal merit of Sontag’s account that she manages to speak about art as a rigorous experimental endeavour, to be understood in its ethical relation to a wider social totality. Whilst not wishing to reduce the manifold ills of contemporary art in its current configuration to an Archimedean point of failure, it is certainly worth considering that its inability to find an audience outside of itself, or bear any relationship to ‘the real’, derives from its relative insularity as a discipline. When it comes to questions of knowledge and truth, and how art can be thought of as a process of revelation, the conviction of this essay is that art must become more ethical, meant in the very precise sense that art needs to rethink its relational role to society and the wider circle of knowledge production.

Grasping the Nth-Dimensional

Despite current trends, arguments which cast doubt upon the traditional, subject-oriented conception of truth proffered by contemporary art are by no means new. Fredric Jameson writes, as early as 1981, that:

…the phenomenal experience of the individual subject— traditionally the supreme raw material of the work of art— becomes limited to a tiny corner of the social world, a fixed-camera view of a certain section of London, or the countryside, or whatever. But the truth of that experience no longer coincides with the place in which it takes place. The truth of that limited daily experience of London lies, rather, in India, or Jamaica, or Hong Kong; it is bound up with the whole colonial system of the British Empire that determines the very quality of the individual’s subjective life.[3]

There comes into being, then, a situation in which we can say that if individual experience is authentic, then it cannot be true; and that if a scientific or cognitive model of the same content is true, then it escapes individual experience. It is evident that this new situation poses tremendous and crippling problems for a work of art…[4]

What Jameson had prophesied as early as the 1980s has now come to pass in the first two decades of the 21st century in myriad ways. The Coronavirus pandemic serves as only the latest prescient example of a situation that demands to be thought about in NthD complex terms. Global pandemic is— trivially— a problem at global scale. But we should not be satisfied with the explanation that ‘global’ means simply affecting any of the various points on the globe one might care to inspect. Instead, we must understand the meaning of ‘global’ as a consequence of many combined, interrelating, and therefore complex[5] factors. In other words, we must take into account the continuous dimension of global scale. Only by so doing can we treat it as a political problem at planetary scale. Precisely because the likelihood of such a pandemic has been increased by certain structural factors, we can consider much of the suffering and trauma it has inflicted to be preventable. These complex factors are rarely seen directly from the perspective of subjective human experience, often bearing the consequence of undermining a person’s belief in them. If the political nature of this problem is of a complex and structural kind, then a large part of the political task must be to unmask and make apparent the truth of its complexity. This task is made all the more urgent against the tide of a popular lapse into interpretations based only on proximate causes, or much more insidiously conspiracy-mongering.

In an exceptionally rigorous and illuminating article, the political journal Chuang offer just such an analysis of how certain structural factors, extremely complex in nature, led to the initial outbreak and spread of Covid-19 within mainland China. A good maxim to adopt in any discussion concerning complexity is to look not for final or ultimate causes, but instead to enumerate causal factors, perhaps adding various coefficients to these where relative influence can be determined. Here, we are provided with evidence of how the early outbreak was caused by global norms and industrial standards of agriculture through territorialisation and capture of every single square inch of space, how domestic factors relating to local healthcare and inadequate communication between local and central authorities lead to widespread proliferation in the earlier stages of pandemic, and so on.[6]

The key point to note in this illustration is as follows: Covid-19 has ravaged global populations and inflicted widespread trauma on many people in ways that are registered locally, be it in the form of personal loss, or painful experiences of suffering with respiratory illness and its long-term complications. In any case, these intense experiences mainly occur at the discrete level of the local (which needn’t just be spatial; local here includes the intimate and personal). It is unavoidable that people will seek some possible interpretation for their personal tragedies; many are right to claim that that their national governments did not take adequate steps to prevent a likely harm, others focus more on the proximate cause of the disease itself, others still turn to conspiracy theory to attribute blame. It is sadly less often the case that one will interpret one’s own suffering by way of a robust structural and systemic account like the one provided to us by Chuang. The contention is, however, that it is incumbent upon us to do precisely this. Such a task will, of course, demand some form of compression of information, it will most likely be imperfect (it is no worse off for having this asymptotic tendency that doesn’t amount to perfect knowledge), and most fundamentally it ought to have some kind of appeal such that it can compete with the rival interpretations suggested above (art and cultural figurations[7] are well-placed to achieve this).

Global pandemic is just one possible and particularly relevant configuration of a multiply realisable question concerning the relation of local sites to the continuous, NthD complex planes in which they are implicated. Our lives are determined by conditions of NthD complexity across a wide range of vectors, ranging from computational information networks, to economic realities, to public health, to geopolitical scenarios. What this tells us is that we can no longer rely upon the standard political models of the 20th century to adequately address problems of NthD complexity; we at very least must radically revise and update how we think about political and ethical questions. Take labour issues as an example: the conditions imposed by NthD complexity mean we need to figure (or, figurate) the ‘virtuoso’[8] type of labour organisation now relied upon by globally distributed commodity supply chains within our conception of working class struggle. Crudely put: the factory floor is simple in comparison to transnational logistical chains operated by a casualised labour force. We ought to keep sight of the fact that we are speaking here of both the global and the complex, that global capitalism strives not for homogeneity but heterogeneity, diversity, and therefore complexity.[9] In the first instance, labour, in being made to meet the demands of seamless operation at global scale, has taken the form of a perpetual performance, one’s subjectivity is wholly determined by one’s job, and one’s work can be omnipresent within the frame of phenomenal experience for up to 24 hours a day.[10] Even outside of work itself, experience does not escape capture. As the Chuang article points out, even what might have traditionally been called the ‘wilderness’ or more formally the periphery of capitalism no longer exists in such terms.[11] Every aspect of life is already subject to capture, everything can be converted into data.

These are also processes characterised by reciprocity, which is to say they are cybernetic. We are entangled in conditions of universal capture in ways which both convert all aspects of our behaviour and determine our unconscious activity and habits. Our ‘leisure’ activity is algorithmically collated into large data aggregates or forms of information and fed back to us, usually in the form of targeted advertisements, but increasingly in more insidious ways such as surveillance and predictive policing. We should note here that the cybernetic relationship between individuals and the NthD complex phenomena in which they are embedded may offer us some potential access to ‘the real’ of the continuous. Such a view is well articulated by Amy Ireland,[12] however any detailed analysis or reflection on these points is not possible within the scope of this paper. Our concern is merely that reciprocal relations between subject and apparatus of capture only heighten the level of complexity and render the NthD complex reality more difficult to parse from everyday experience.

Finally, there is a great deal of opacity concerning computational forms of capture and the networks they comprise, into which our individual selves and localities are integrated. Such networks cannot be considered as textual, and therefore their minute operations cannot be interpreted semantically.[13] Thus they resist the hermeneutic strategies of ordinary experience. To add to the opacity, the software itself which collates the data and converts it to applied information is often proprietary and beyond the grasp of individual actors or non-corporate entities.[14]

The upshot is that the conditions of our given experience are largely determined by factors not only too complex to be grasped all at once, but often also to which individual agency has little recourse. Of course, by dint of their artificial constitution much of what we speak of here is a consequence of human engineering and therefore can be made subject to a political demand for revision. However, the important point is simply that we cannot consider questions of truth, and attendant questions about what we should do at the levels of ethics and politics, merely from the information that is available to us within given local experience. We should not take this revisory statement to mean that the manifest image of experience should be negated completely. It is rather, in Wilfrid Sellars’ original formulation of the question, a matter of how we understand and modify the relation between the manifest and scientific images.[15] That is, how can we bring the truth of the continuous into the local and discreet, such that an adequate synoptic image of reality becomes available to us?

Knowledge of the Complex

Now we turn to address the question of how knowledge of the NthD complex realities in which we are embedded is possible, and can therefore be made potentially navigable, a question which— it must be said— is the subject of much recent contemporary theory.[16] In the first instance, the question may be asked: how do we characterise the NthD complex in general, of what nature is it? And so on. But we may also ask: what is our relationship to it, how do we know it? It should be noted here that we can attempt to answer the second question without holding a completely satisfactory answer to the first.

Indeed, we will not attempt to construct any ontological thesis about the NthD complex, instead opting for a more descriptive, epistemological account. This puts some distance between our objectives here and the approach of Object Oriented Ontology (OOO), which attempts to answer these same speculative questions by conceptualising NthD complex phenomena as objects, analogous to the object classes in object-oriented programming.

A representative example of one such account is that of Timothy Morton’s ‘hyperobjects’,[17] a critique of which may here prove edifying in certain respects. To crudely summarise Morton’s project: he holds that NthD complex phenomena can be classified as objects, that these objects are ‘withdrawn’ from us, but that we can partially know them through poetic modes of revelation. Perhaps confusingly, while Morton suggests we cannot fully know hyperobjects, we can come to have better knowledge of them by dissolving the separation between humankind and nature, thereby engendering greater relations of ‘intimacy’ with hyperobjects. Thus, Morton’s poetic modes of revelation are founded on a kind of slow, intimate reflection, a Heideggerian poetics of presence.[18]

The salience of discussing Morton and OOO here has to do with the general reception such accounts receive within the ambit of Contemporary Art (CA). Indeed, to the extent that CA addresses some of the questions we have thus far been considering, it is very often the framework of OOO which commands a great deal of influence and cachet within the art-world at present. Here, we should once again consider Jameson’s predicament, wherein the work of art becomes crippled by its inability to adequately account for what is beyond local experience. Would it not be true to say here that if Morton’s account is correct, in which we can come to know about the NthD complex via poetic intimacy, then Jameson’s worry about art is in fact misplaced?

To look at things from a different angle, Suhail Malik critiques CA’s indeterminacy in the following terms: the contemporary artist has an interest in many subjects, but the only demand made upon the contemporary artist is to express the singularity and particularity of lived experience.[19] At the same time, CA bemoans its inability to make contact with ‘the real’ outside of itself. CA lacks any kind of traction within the world outside its own sphere of influence, and aside from established artists whose work is collected by large public institutions or blue-chip galleries, art has vanishingly little contact with a non-art audience, nor society-at-large beyond the social milieux of practicing artists. Art becomes hermetically sealed, and its tepid engagement with the sciences or other forms of knowledge creation reinforces superficiality at best (certain exceptions notwithstanding). As Malik suggests, whilst the contemporary artist may make a gestural claim to some area of interest or significance beyond the mere reproduction of the individual artist’s practice for its own sake, they are rarely compelled to give an account of why their unique personal perspective matters. Apparently this is because there is nothing external to CA which would give us some invariant terms to evaluate the validity of the truth claims being made by experience.[20]

Now let’s return to Morton and ask the following question: how can we evaluate the truth claims about the meaning of one’s particular poetic revelations about hyperobjects? In other words, how do we know that what we are experiencing is really the hyperobject ‘global warming’? What is notably absent from Morton’s account is any analysis of language and its relationship to the production of knowledge. As McKenzie Wark points out in her critique of Morton, the singularity of knowledge production qua poetic revelation effectively obviates the entire labour of climate science which makes any kind of knowledge or discourse about such hyperobjects possible in the first place.[21] In Morton’s conception, ‘hyperobjective knowledge’ can merely amount to glib truth claims about personal experience. All experience is thus equally valid, and a greater quantity of experiential truth-claims— precisely what makes CA indeterminate— is simply taken at face value as a good thing as far as truth is concerned.

For Morton’s account, there seems then to be no viable method to adjudicate between the competing arguments of two individuals to establish the truth-value of a claim such as, for example, global warming’s existence. This is to say: we need climate science to act as the ultimate arbiter between competing experiential claims. Otherwise, when one person says “global warming exists because I can see that there are fewer days of frost with each passing year”, and another exclaims “global warming does not exist because it’s -20 and snowing outside”, both can be said to be making equally valid and useful claims. Ostensibly, the failsafe in Morton’s argument to prevent this outcome is his ontological conception of hyperobjects, but ultimately his justification for this amounts to a metaphysical posit. This is to say that whilst Morton obviously does not hold that both accounts in this climate argument are equally valid and true, little is available to us— from his account— by way of criteria for determining which statements are true, or more importantly what conception of subjective ethics ought to be adhered to in pursuit of the truth. In fact, it is precisely a consequence of an emphasis on ontology that, by design, very little is required of the practitioner of knowledge production. Since the truth of what is exists ‘out there’, the only requirement on those seeking to articulate it— artists, for one— is to feel it, and to simply convey that feeling adequately. This is a discussion about what is, which conveniently looks in the other direction when asked to give an account of how we know what is or by what right we know it. The absence of such criteria is highly suited to a CA system which tends to valorise the work of artists with reputational capital, whose work panders to the interests of the art-patron class, or whose work might be subject to capitalisation by some other means. The claim here is not that OOO is somehow cynically in collusion with the power-brokers of CA to fashion a suitable conceptual armature. It’s simply that there are clear reasons why CA would so readily endorse a philosophical outlook devoid of any specific requirements upon its practitioners, when the criteria for successful art is so often devoid of any specific meritorious characteristics of the artist’s practice. It’s a cheap and dirty solution to Jameson’s challenge: slap the label ‘hyperobject’ onto any chimerical aspect of experience, proclaim it to be withdrawn, ineffable, intractable to further decomposition or understanding, and then just go back to whatever you were doing before, satisfied that you have adequately accounted for the continuous now that you have named it. Surely we can hope for better than this.

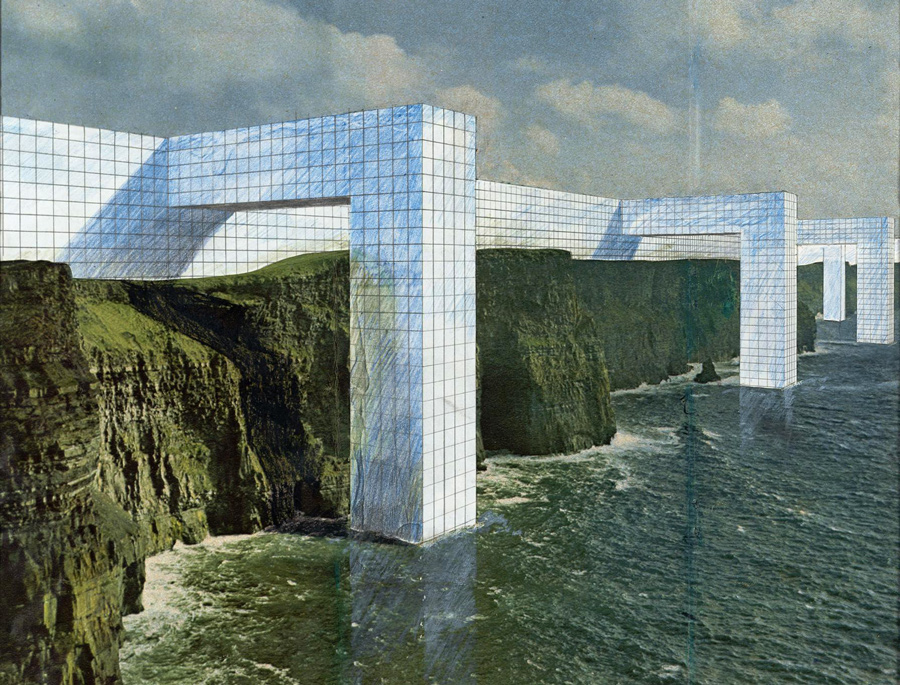

Let us cleave instead to the epistemic approach, without attempting to give NthD complex phenomena any constitutive identity. We ought to enquire about the nature of our relationship to the continuous beyond the immediate frame of experience, which means starting from the constraints and limitations of that experience, rather than postulating in advance that there is some greater nature to the NthD complex which needs to be revealed. (It should be noted that such claims about our relation to the continuous already smuggle in certain prejudices about what we might expect to find, an unhelpful determinacy unlikely to aid us in answering the real difficult questions around navigation). Patricia Reed suggests a helpful framing of the problem, arguing that the task of navigation at planetary scale involves a recasting of the local of experience as being on a continuum with the more abstract NthD complex planetary scale.[22] Therefore the task becomes not one of poetic revelation through a deeper intimacy of local presence, but rather a hermeneutic task of constantly revising our relation to the present of experience. Crucially where this differs from Morton’s account is that whereas in the latter, a certain givenness of fact is already established at the moment of experience, in Reed’s version this is precisely the thing which cannot be assumed in advance. Thus the matter of coming to understand our relationship to the continuous from the perspective of discrete experience demands the development of certain conceptual and practical tools. In a similar vein, Reza Negarestani advances the argument that in thinking the local from the perspective of the global, the former “cannot preserve its constancy”,[23] a new discrete is produced via procedural generation when we gaze and begin to act through the transfiguring lens of the continuous.[24] This moment of taking up the point of view of the universal to reconstruct the local is generative, rather than just revelatory, in that it is a synthetic operation, both in terms of its relative coordinates and its interconnection to the non-discrete beyond the limits of its horizon. In other words “universality becomes the operation of productive locality which is globally oriented.”[25]

So far we have seen that the poetic won’t work in isolation, but rather needs to be supplemented by something else in order to give us some kind of knowledge and orientation. We are not canvassing for the suggestion that poetry beholds no truth, but instead placing emphasis on the terms and conditions under which artistic revelation is to take place, demanding something of the practitioner beyond the mere fact that they happen to be speaking whilst holding an MFA from a qualifying institution. The objective is not so much to turn artists into scientists, to ‘hold artists accountable’— indeed the motivation for this essay is to avoid precisely this impulse in which artistic production becomes overly rigid and dry on account of efforts to continuously justify itself and appear thoroughly sensible. The present impasse in art certainly will not be resolved by further forays into the bland world of ‘relational aesthetics’ or so-called ‘publicly engaged art’ (as opposed to what other kind?). What is decisively not meant by the call here for a subjective ethics of art— much as it is lamentably and unimaginatively interpreted as such— is also not a matter of the individual artist (performatively) being a ‘good person’. It is especially not about the artist conspicuously caring about political issues or themes; the dialectic of the bleeding heart lands us squarely back within the ambit of market-driven art production and its obsession with discrete individuals. To avoid any misconception then, what is argued for here is, again, an ethics, writ-large and in its positive dimension, which crucially must contain an element of experimentation. Experimentation here is not to be conceived of as the kind of juvenile randomness that gives the avant-garde a bad name. It is a rather more purposive form of experimentation and investigation, as we shall discuss in short order. This forms the bridge connecting art as it is and ought to be practiced with the role of the artist in Sontag’s locution.

We should address our question in more positive terms then, for if the given of experience needs to be re-framed in order to expand beyond the merely local, we should try to answer the question of how it can be done, at least in general terms. In a most basic sense, it seems that to adopt a perspective that is extra-local, something in addition to what is provided to immanent sense experience alone is required. What this ‘something’ is can be answered in a number of different ways. As we’ve already seen in our critique of Morton’s account, the assumed and implicit fact of scientific language, sedimented into general public discourse, is what allows us to fix some more determinate framing to the nature of our experiences. According to Morton, this fact is already pre-existing and uncredited, it is already implied and therefore never subject to any critique. Thus the description of those aspects of experience which hint at the continuous lying beyond the discrete are simply named and reified as hyperobjects.

A more rigorous conception holds that there is a certain labour required on the part of the artist, which progressively builds a capacity through practice enabling one to articulate novel and meaningful truths of experience. Fundamentally, experience here is being challenged rather than valorised as uniquely important in its given structure and interpretation of reality. But the point here is that experimental practice which re-frames and re-negotiates the conditions of our experience in order to perturb the givenness of the local cannot be so easily achieved. It is one thing to express this wish in relatively abstract terms, and quite another thing to put it into practice. Such are the limitations of writing about it to begin with, which is not to say that the usefulness of doing so ceases at this point. It is however to say that such an idea adheres to the Marxian sense of sensuous social practice, in which a social reality is to be deduced from its appearance through practice within the sensuous domain, not thinking within the ideal or spiritual domain.[26]

In striving to understand the nature of dimensionally complex realities beyond what is merely already available through observation combined with common knowledge, the artist attempts to produce new truths of experience in the way we articulate and understand the relation of the local to the continuous. This must take a form which meaningfully combines thinking and doing, or research and practice. It would not be unlike what professional fine art programmes often already aspire towards but invariably fail to live up to as a consequence of market-driven rationalisation amongst other factors. Taking the practice of art seriously as a discipline that produces knowledge like any other both requires and provides the basis for restoring it to a degree of social relevance.

The artist, in a sense, ought to adopt certain strategies for investigating the outer frontiers of consciousness in relation to the NthD complex. This means to step away from the decidedly bourgeois conception of art best conceived as luxuriating in wonderment at one’s own surroundings; or, that one simply deserves to be a recognised artist by dint of having a unique experience, taken merely in the sense that all experience is qualitatively individual and by virtue of this fact alone, unique. As a relatively incidental but no less important point, there are some pretty troublesome implications of the status quo of art which currently amounts to such a view. The default of an indeterminate art world is that those who get to become artists (save some notable exceptions) are individuals with some ostensibly unique way of seeing things which cannot be reduced to any kind of effort or acquired ability. On this reading, some individuals are simply predisposed to have a unique way of seeing things, but should we not ask: what is the nature of this predisposition? If we cannot attribute it to any kind of learned ability on behalf of the artist, then we are only left with conclusions such as genetic or social inheritance. We need only consider the general homogeneity of class and race positions occupied by the majority of successful artists within CA to see how this is simultaneously insidious and false in its suggestion. Thus, although questions of representation in the arts would not be comprehensively solved by addressing the question of indeterminacy, at the very least doing so would be in part a project of unmasking CA as a haven for lazy middle- and upper-class charlatans who succeed in the CA market simply because they reproduce an experience to which those with financial power and social clout in the art market can relate.

Digression aside then, what strategies can we make use of to integrate the NthD complex into the local, and thereby reconstitute local experience? As already suggested, this can only be comprehensively answered through the trials of sensuous practice; however, theoretically we can still equip ourselves with certain useful tools that point us in the right direction. One such strategy which springs immediately to mind is that of Fredric Jameson’s ‘cognitive mapping’. In Jameson’s own words:

…cognitive mapping in the broader sense comes to require the coordination of existential data (the empirical position of the subject) with unlived, abstract conceptions of the… totality.[27]

Here in this general formulation, cognitive mapping seems to describe a very similar process to what was earlier described philosophically by Negarestani and Reed. Crucially, what is added by Jameson is a specific practice or general toolkit of practices to accommodate our theoretical ambitions. Jameson goes on, for example, to describe cognitive mapping practices in relation to navigational technologies, processes through which agents can triangulate features of their immediate perceptual environment to orient themselves. This can importantly be further extended into the domains of art and culture. Jameson retrospectively applies this term to a 1977 essay on the Sidney Lumet film Dog Day Afternoon to describe how characters in the film become ‘figurations’ of sociological realities on its outside. Thus the global conditions of the film’s possibility, which are occluded from within the narrative plot of the film itself, become visible when we consider the film as an artefact.[28] Again, here in Jameson’s words:

…the external, extrinsic sociological fact or system of realities finds itself inscribed within the internal intrinsic experience of the film in what Sartre in a suggestive and too-little known concept in his Psychology of Imagination calls the analogon: that structural nexus in our reading or viewing experience, in our operations of decoding or aesthetic reception, which can then do double duty and stand as the substitute and the representative within the aesthetic object of a phenomenon on the outside which cannot in the very nature of things be “rendered” directly.[29]

Of course, in this instance, the cognitive mapping is by Jameson’s own admission most likely incidental, the result of an external, hermeneutic process performed by Jameson himself, or supposed to be performed by the audience of the film. But there is no reason why such practices might not be adopted directly and consciously into the activities and practices through which art is produced.

Unlike with Jameson, ours is not a hermeneutic task but a programmatic one. This should shift our primary concern away from existing artworks and towards a hypothetical construction of the artist. There is a clear analogue here between the question of the artist’s subjectivity and questions of the self pertaining to ethics. Our point of departure here must take the artist not as a given unity but a constructible hypothesis, just as we should assume the self to be a constructive endeavour under certain constraints in thinking about subjective ethics. That is to say, the question of “what should I do?”, is somewhat gerrymandered because it expects that we always approach the ethical situation as a novel phenomenon and without any prior orientation. It also assumes that we always have enough time to ask ourselves the question of what we ought to do, and that this is a feasible strategy for ethical agency in general. Finally, such a formulation often relies upon a negative formulation of ethics, namely where “what I ought to do” is given a highly restricted set of possible choices, as opposed to a more spontaneous and open-ended plane in which the question is a matter of determining a course of action rather than predicting and deciding between possible outcomes. More often it is the case that we make ethical decisions in real time on the basis of general rules which ought to be revised, reflected upon, and interrogated (though unfortunately often are not), and we construct a version of who we are as an ethical agent in a practical sense. We should think of artistic practice in just the same way precisely because it is an extension of ethical practice thus conceived. Thus, we do not have to ask ourselves in each literal instance what we ought to do, leading to paralysis and conceiving of practical agency in the highly restrictive negative sense outlined above. Instead, artists attempt to construct their own agency through a heuristic process which is mediated by reflection, self-critique, and questioning of the relevance of what they are doing via some broader world-conception than that which concerns them at the level of local experience. The incorporation of schema such as cognitive mapping can be considered as one example of a useful approach towards achieving this.

This notion of construction and revision also opens up certain possibilities for genuinely collaborative art, since in this instance the act of collaboration would not be one of negotiating around pre-given identities and styles in competition with one another, but instead a matter of constructing a collective process. From this vantage point, we can consider how the artist constructs a relation to the world as prior to and informing the question of how well individual, discrete artworks represent the NthD complex realities. Evaluating how art can engage with the continuous from the local and discrete perspective depends entirely upon the development of certain cognitive or technical skills, tools, and synthetic abilities which must be cultivated and developed prior to the production of a given artwork, and thus which precondition all works of art authored by the individual artist in question. In a sense, one could easily make the association here between the cultivation of cognitive mapping skills and more traditional conceptions of the development of an artist’s craft. However, unlike this traditional sense of craft, there is a definitive cognitive component that is outward-facing with respect to the artwork in question. In other terms, we evaluate the ‘goodness’ (for want of a more precise criterion) of a work of art not only in respect to criteria specific to the work’s own conditions of production, but in terms which speak to the artwork’s wider relevance to the world in which it exists.

Artificial Memory and Procedural Generation

At the very beginning of this paper, the question posed concerned the role of the artist in investigating the limit points of consciousness or experience. We shall conclude things therefore by synthesising this question of conscious experience with some possible strategy for embedding the NthD complex within the local. What has hopefully become clear through the course of this investigation is that some strategy to change how we as individuals— meaning artists and cultural producers for our purposes in this essay— might go about transforming ourselves and our practical relationship to the world such that it is possible to accurately render the truth of experience which is not merely subjective or given. Jameson’s cognitive mapping provides us with a methodological intervention at the level of specific artworks, but perhaps its real value is not merely its problem-solving capabilities when it comes to the production of discrete works of art, but as has already been suggested, its capacity to forge new ways of being in relation to the world as a practical subject. It might be that artistic producers begin by incorporating a tool such as cognitive mapping into their artistic production, but one should also expect that from undertaking this practical activity a new way of seeing the world in general ought also to emerge.

Bernard Stiegler’s conception of the interplay of anamnesis and hypomnesis proves conceptually useful on this front.[30] In short, anamnesis denotes the internal organisation of memory by an individual, whereas hypomnesis is the externalisation of memory into the wider domain of knowledge. One can see then how this might capture the sense of relation between the individual and the complex knowledge realities which make up the NthD complex. Stiegler’s object of critique concerns how the ‘grammatisation’— “the process whereby the currents and continuities shaping our lives become discrete elements of hypomnemata”[31]— by ruling classes imposes too great a constraint on the possible forms of human knowledge and agency. Our access to general externalised knowledge— the composition of the knowable NthD complex as far as art is concerned— is tightly controlled and restricted.

Here it is important to clarify the role of art in relation to the NthD complex; this is precisely the question of how to update art’s relevance by understanding its positional relation to other modes of enquiry. Unlike in previous epochs, there is nothing which can now be said to evade the gaze of universal capture. Everything that exists can be rendered as data, even if we do not have a singular or correct semantic interpretation of that data. As with philosophy and other disciplines, it is no longer the realm of art’s role to make new discoveries concerning entities or empirical phenomena, which should be delegated instead to empirical science. But art still has much to say when it comes to investigating the limits of the self in relation to the vast quantities of information about the NthD complex given to us via science and related disciplinary fields. This is to say, art qua experimental ethics is a matter of investigating the limit point of the conscious subject within the context of global-scale complexity. Art uncovers the truth of experience, but ought not to hypostasise experience uncritically as truth. The artist’s role is then two-fold: to develop certain methodologies and practices to integrate scale and complexity into the local and thereby transform it, and in so doing, to rigorously investigate the outer limits of subjective experience produced by these new, procedurally-generated localities. The process by which this is done could be considered analogous to Simondon’s process of individuation, in which the role of the artist becomes one of individuating the corpus of complex knowledge and data.[32] Crucially, the process of individuation is not one of generating identities via the law of excluded middle; rather, the individual is metastable, and the artist’s procedural and generative process of individuating totalities of knowledge takes place at a stage that is prior to rigid identification and concretisation, meaning it is in the experimental phase of investigation. We note here that this works well for art, which does not and indeed ought not make strong truth-claims to which it can hold with certainty. Because the claims of art can be tentative, it is possible and even necessary that they be put forth in such a metastable way. This is, however, in no sense to argue that the practices through which artistic production brings these claims to bear ought to also be indeterminate or carried out with a bad-faith epistemology.

Turning once more to Stiegler’s challenge of how anamnesis can penetrate into the hypomnematic realm of knowledge, the task for art becomes that of developing an array of artificial techniques. Indeed, the development of technique is not without historical precedent and though it would be an entirely different study to attempt to survey these, we can at least provide an example. The classical memory arts, and in particular the occult artificial memory system developed by Giordano Bruno as detailed in Frances Yates’ historical survey of the tradition, might be re-appropriated as a possible structural basis from which to take up the practice of developing techniques with significance for artistic production.[33] In essence, this amounts to the demand for the development and cultivation of skill, to dive deeper into the vast quantities of information, to acquire and perhaps memorise as much of it as possible in order to open up possibilities for new, recombinatory possibilities and play, thus over-running the crippling grammatisation imposed by regimes of capture and control.

Our focus here on memory is not altogether incidental. In the background of all that has been argued for in this essay is the problem of the displacement of the human. In the information age where NthD complexity of continuous realities appears to exceed the boundaries of what can be cognised by any individual alone, if not by humanity in general, an emergent neo-reactionary movement has begun to celebrate this onset of decline and ultimate extinction of the human. To respond to this challenge, I want to draw upon a useful distinction made by Giuseppe Longo concerning the difference between human memory and computational memory:

In computer science, everything is done in order for databases (and communication) to be exact, pixel by pixel. The Web (Internet), this extraordinary “database” for humanity, potentially available to all, must be exact: there lies its strength… This is the opposite of intentional, selective and constitutive dynamic of meaning and invariance, in the variability, in the active forgetfulness which is animal memory, in which the forgetting of irrelevant details contributes to the construction of the relevant invariant, the very intelligibility of the world… What a mistake to believe that the relevance of digital computing was to be the artificial copy or replacement of human intelligence: it did much more, it enriched it in a revolutionary way.[34]

Memory then captures precisely what is at stake. When dealing with complexity, we are necessarily engaging in some form of compression of the metaphysical variety.[35] The notion of generating artificial memory techniques is a question not of a veridical and indexical reproduction of the whole, but a praxis of procedurally generating a revisable body of rational knowledge.[36] This means that the knowledge gained through the compressive operation or synthesis is always at metastable equilibrium,[37] subject to revision and constant (re)individuating processes. Even in our ethical conception of the practical subject as a hypothetical construction, we must begin by taking subjects— as necessarily local and with certain biases and prejudices— as our starting point. One might add that no subject is too virtuous so as to be exempt from this procedure. If such biases already take the form of a compression of information, then the task of the artist in the sense of experimental ethics is that of transgressing the limits of said biases, perhaps renegotiating them, bringing about the displacement of the local through the adoption of an associated milieu[38] of the NthD complex and global, not in order to arrive at some ideal, uncompressed state, but to achieve a more adequate form of compression which allows us to better navigate our world in all of its complexity. As Sontag has best illuminated, this may demand a certain radical openness to revision, to be leveraged through specific practices, but it is perhaps fundamentally inaugurated by a certain ‘romantic’ attitude towards the adventure that artistic practice purports to undertake.

- Susan Sontag, “The Pornographic Imagination”, Partisan Review 34.2, 1967: 181–212.

- Hereafter ‘NthD’ will be used to refer to ‘Nth-dimensional’ and ‘Nth-dimensionally’ interchangeably. The reader may use their own discretion to determine the appropriate formulation in different particular contexts. The phrase ‘Nth dimensionally complex’ is adopted from Patricia Reed, ‘Orientation in a Big World: On the Necessity of Horizonless Perspectives’, e-flux #101, 2019: 8. I have found this to be an incredibly useful formulation as it captures the dimensional or qualitative aspect of planetarity, making apparent that this is not simply a question of large quantities but also the different levels of reality and the dimensional variance of laws governing how they function. This will be discussed in more detail in a later section.

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, 2. print. in pbk., [Nachdr.] (London: Verso, 2007), p. 411.

- Ibid.

- We should take care here to distinguish between complex in its more exact sense as meaning the manifold connections between several different parts which characterise a system or structure, and the more rhetorical sense as meaning something overwhelming or difficult to interpret. Although the facts that give rise to its use in the latter sense are important to my general argument here, I use complex strictly in the former, more exact sense.

- Chuang, “Social Contagion: Microbiological Class War in China”, Chuang, 2020 <http://chuangcn.org/2020/02/social-contagion/>.

- I will use the notion of ‘figuration’ throughout the paper, adopted from Jameson. See Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, pp.30-36.

- For ‘virtuoso’ labour, see Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents Series (Cambridge, Mass; London: Semiotext(e), 2003).

- See Anna Tsing, “Supply Chains and the Human Condition”, Rethinking Marxism 21.2, 2009: 148–76 <https://doi.org/10.1080/08935690902743088>.

- See Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect (Cambridge, UK?; Malden, MA: Polity, 2012), 101-19.

- See also Robert G. Wallace, Big Farms Make Big Flu: Dispatches on Infectious Disease, Agribusiness, and the Nature of Science (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2016).

- See Amy Ireland, “Noise: An Ontology of the Avant-Garde”, in Aesthetics after Finitude, eds. Baylee Brits, Prue Gibson, and Amy Ireland (Melbourne: re.press, 2016), 217–27.

- Alexander R. Galloway, “What Can a Network Do?”, audio lecture 2009 <http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/mp3/Galloway,%20What%20Can%20a%20Network%20Do,%20Barcelona.mp3>.

- See Ned Rossiter, Software, Infrastructure, Labor: A Media Theory of Logistical Nightmares (New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2016).

- Wilfrid Sellars, “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man”, in Frontiers of Science and Philosophy, ed. by Nicholas Rescher (Pittsburgh: Univ Of Pittsburgh Press, 1963), 35–78.

- See Kodwo Eshun, “Recursion, Interrupted”, e-flux #109, 2020 <https://www.e-flux.com/journal/109/331340/recursion-interrupted/>.

- Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, Posthumanities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 27.

- See also Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought, ed. Albert Hofstadter, Works / Martin Heidegger, CN 430, 1st Harper Colophon ed (New York: Perennial Library, 1975), 211-227.

- Suhail Malik, “The Problem with Contemporary Art Is Not the Contemporary”, lecture given 2013 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJkHb0YsdLM>.

- Ibid.

- McKenzie Wark, General Intellects: Twenty-One Thinkers for the Twenty-First Century (London; New York: Verso Books, 2017), 538-70.

- Patricia Reed, “Orientation in a Big World: On the Necessity of Horizonless Perspectives”, 8.

- Reza Negarestani, “Where Is the Concept?”, in When Site Lost the Plot, ed. Robin Mackay (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2015).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Karl Marx, “The German Ideology”, in Karl Marx and David McLellan, Selected Writings, 2nd ed (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, 52.

- I adopt the use of artefact here from Negarestani. See Reza Negarestani, Intelligence and Spirit (Falmouth; New York: Urbanomic; Sequence Press, 2018), 10-11.

- Fredric Jameson, Signatures of the Visible (New York: Routledge Classics, 2007).

- 72.

- Bernard Stiegler, ‘Memory’, in Critical Terms for Media Studies, eds. W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), 64–87.

- Ibid., 70.

- Gilbert Simondon, :The Genesis of the Individual”, in Incorporations, eds. Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter, Zone 6 (New York, NY: Zone, 1992), 297–319.

- Frances Amelia Yates, The Art of Memory, Selected Works / Frances Yates, v. 3 (London; New York: Routledge, 1999).

- Giuseppe Longo, “Critique of Computational Reason in the Natural Sciences”, in Fundamental Concepts in Computer Science, eds. Erol Gelenbe and Jean-Pierre Kahane, Advances in Computer Science and Engineering: Texts, v. 3 (London; Singapore; Hackensack, NJ: Imperial College Press; Distributed by World Scientific, 2009), 43–70. (Quote 66-67.)

- For an account of ‘metaphysical’ compression, see Alexander R. Galloway and Jason R. LaRivière, “Compression in Philosophy”, Boundary 2, 44.1 (2017): 125–47 <https://doi.org/10.1215/01903659-3725905>.

- Negarestani, “Where Is the Concept?”.

- Simondon, “The Genesis of the Individual”.

- See Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2016), as well as Gilbert Simondon, “Technical Mentality”, in Gilbert Simondon, eds. Arne De Boever, Shirley S. Y. Murray, and Jon Roffe, trans. Arne De Boever (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 1–14 <https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748677214.003.0001>.