Isn’t community outside intelligibility?

–Maurice Blanchot1

In a recent seminar, Jason Mohaghegh posed a question that even many avant-garde movements were too cautious to ask: “What would thought look like without any formulation of reality?”2 I would like to briefly explore this question in another form: What would community look like without any formulation of reality? Mohaghegh suggests the common thread that unravels utopian experiments of community into violent, tyrannical ideologies is their dependence on a reality principle they must enforce. In a world where communities are often so fragmented and mediated as to seem nonexistent, or else imposed with such dominance as to suffocate diverging potentials of life, it is tempting to reject the concept and retreat from its collective aspirations. Alternatively, we can keep imagining possible modes of community in a different way – by attempting to formulate them around something other than the real.

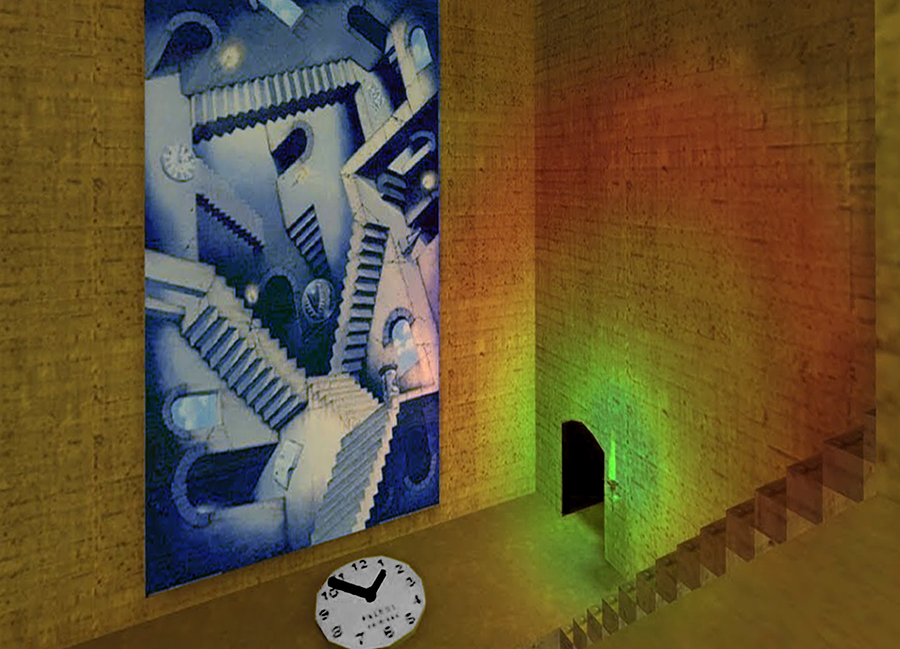

When we experience the world around us, we are enveloped by multisensory phenomena that move in ecstatic relation to our bodies and surroundings. Immediate yet shifting and multiple – at times almost intangible – perceptual worlds are microclimates that permeate and exceed us. As we breathe them in, they shape our affects and potentials, even as we project imagistic emanations into their midst. These synaesthetic environments could already be considered spaces of irreality that all living beings partially inhabit. This is not exactly the “real” world but it still clearly exists outside ourselves.

The concept of irreality appeared on the margins of Surrealism, among figures such as Le Grand Jeu and Max Blecher. While it is unclear if they knew of each other, they all discovered a possibility opened by the irreal, which arose more from elemental experience and desire than any contemporary discourse. As Jason pointed out, irreality does not define itself in terms of the real or unreal – “irreality just takes everything as neither condition.”3 For Roger Gilbert-Lecomte, the irreal offered dangerously generative powers of malleability, while for Blecher it was most often a swarming catastrophe on the verge of consuming the world. For both it seems that eruptions of irreality were recognizable through their qualities of the indefinite, metamorphic, elusive, immediate and multiple.

At the limits of our awareness, our sensitivity reaches and dissipates into the unknown. This threshold is the space of collective encounter, which itself can become an emergent presence irreducible to individual perspectives. It remains incomprehensible because it is always partially beyond each of us, moving and withdrawing as we move within it. This presence could just as well be considered an absence – a mode of being there and not there – because it does not exist as a cohesive totality in any known substance or form (but do we?). At the same time, it has powers to immediately shape and perhaps even become the world, like flickering shadows of leaves swirling together and taking on a life of their own.

I have investigated phenomena of irreal presence mostly through the lens of the senses, but am coming to realize they can be just as much at play in social environments as sensory ones. This became apparent during two Seminars I offered at The New Centre: “Notes from Immediate Irreality”4 and “Being There and Not There.”5 The themes of these Seminars were nebulous, and the other participants unfurled them into so many varied and unexpected lines. What I learned from this experience was to notice the ways our shared curiosity around something uncertain and undefined could draw us in, holding us together on the verge of scattering. These moments of collective fascination were transient, partial, incomplete – like the Seminars themselves. They were also often indefinite, metamorphic, elusive, immediate and multiple – like, if we can define it as such, irreality itself.

This is why I am suggesting that, at their best moments, these Seminars and many others which tend toward becoming creative research collectives may be early diagrams of community not based on a reality principle, but practiced through evocations of irreal presence. Instead of a shared origin, identity, knowledge, deity, location or reality, what we have in common is a specific, shared unknown that exceeds us all. Our capacity to encounter its potentials, each other and the world that opens around it is equal to our capacity to experience and provoke impersonal fascination – in spaces of irreal presence, “the only logic is fascination.”6 Through the collective improvisation of exploring, shaping and moving together with this living unknown, our common sense of fascination can only grow.

And so once more we conjure a vision of community as perennially unfulfilled, but one that extends an invitation – perhaps from irreality – to enter the space of its presence over and over again.