Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), one of the founders of sociology as a science, undertook a great effort for this area of knowledge to overcome its so-called ideological burdens. For him, “it is necessary to free oneself from the false evidence that dominates the common spirit” (Durkheim, 2004: 64). Sociology should become a science of empirical strength, moving away from any conception of a vulgar a priori nature, i.e., the result of an idealization of reasoning and, consequently, separated from supposed concrete reality. Therefore, this is the first basis of Durkheimian thought: looking at the said facts, beyond pure and simple rationality.

It is from such an assumption that Durkhein derives one of his most important foundations. Social facts must be treated as “things” (2004: 20). With this, it should be understood that the “thing is opposed to the idea as what is known from the outside to what is known from the inside” (2004: 21). At this moment in the development of his thought, Durkheim clashed with the doctrine of classical liberalism as advocated by Adam Smith (1723-1790). The debate revolves around the conception of homo economicus. According to the French author, we would not be able to find empirical evidence of the existence of such a being: its genesis and development are merely part of rationality (Vares, 2011). On the other hand, another feature of this concept also clashes with Durkheimian conceptions. Even if we were able to recognize the historical existence of homo economicus, the foundation that rationality governs all individual actions clashes with the idea of the coercive power of social fact.

We recognize that this debate does not end with Durkheim and Smith. Sociology and the updated version of liberal thought, recognized by the name of neoliberalism, continue to advance discussion between the a priori — before empirical experience —, contained in reasoning, and that of a posteriori nature which focuses on empirical observation. As an example of what we mean, we will cite the work of Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973), namely his work Human Action (1996). In that book, Mises undertakes an effort to “convert the theory of market prices into a general theory of human choice” (1996: 3). For this, Mises seeks the roots for human action in the idea of unconsciousness, in which humans act according to their nature, to satisfy their needs (1996: 13 and 14). However, such an essence is not empirically observable: it can only be understood from the vantage of its logic. In turn, such rationality is only found when we exercise our ability to think a priori.

Therefore, this thought, its bases and foundations, continues to contradict Durkheimian thought; in so doing, it also clashes with the wider sociological tradition. Thus, the aim of this essay is to clarify the contradictions between neoliberal thinking, focusing on its precursors Friedrich Hayek, and sociological thinking as prescribed in the works of important contributors such as C. Wright Mills and Norbert Elias. Our purpose is not to just disparage neoliberal thought, make it invalid or, to use Mises’ parlance, refute it. We merely intend to show its contradiction with sociological thinking. The first section of the essay aims to explore Hayekian thought; in the second section, we will explore sociological thought, highlighting its differences and possible similarities with the other current of thought.

What does Hayek think? Notes on neoliberal thought

Friedrich Hayek was born in Vienna, Austria. He graduated in economics at the University of Vienna and received a doctorate in law and political science from the same institution. Hayek taught at several universities such as the London School of Economics, the University of Chicago and the University of Freiburg. During his stay at such schools, he undertook an effort to consecrate himself in the area of economics, which guaranteed him the Nobel Prize in 1974. The influence of this author’s thinking penetrated the various areas of knowledge such as law, economics and politics. Hayek even had an impact on international institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Thus, we must not, under any circumstances, underestimate the reach of Hayek’s thought. On the other hand, it is imperative to explore it and compare it with other ways of thinking about the social world.

In this sense, Quinn Slobodian, in his book Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (2018), becomes a fundamental commentator on Hayek’s thought. In this section, we will use that author as our main guide. The main idea of Hayekian thought is that the world follows a fundamental logic: it is governed by markets, by an order that goes beyond the social and the political.[1] And, because it is in this position, the claim is that it is not affected by phenomena of a social or political nature (Slobodian, 2018:4). Thus, for the proper functioning of social groups, the institutions that keep the freedom of the market intact must, for Hayek, be preserved and, in several senses, expanded whenever possible (Slobodian, 2018:7).

Yet in turn, for such an effort to materialize, it was necessary to have an international order capable of implementing the laws of the market. Such an order would have a coercive power greater than state sovereignty itself. Even with the end of formal imperialism, nations should remain sub judice of an international order that would safeguard capital and its ability to circulate around the world. If we follow this logic, even democratic regimes should be designed with brakes so that they do not harm, in any way, such market order (Slobodian, 2018: 14).

Despite being contradictory, since the neoliberal order should be reinforced and protected at an international and domestic level, Hayek believed that such order was the result of a self-generating and spontaneous structure. If there were no kind of interference, the neoliberal order would emerge without major difficulties. In this sense Hayek, in theory, did not believe in the possibility of understanding such an order through empirical data (Slobodian, 2018: 226). Hayek was against the use of software and computers for economic research. For him, “the economic order itself was like a huge information processor that was beyond the capacity of human thought to produce or understand it” (Slobodian, 2018: 226). In one of his most emblematic speeches, called “The Pretense of Knowledge”[2], Hayek begins by announcing:

It seems to me that such inability of economists to guide policies more successfully is intimately connected with the propensity to imitate, as rigorously as possible, the procedures of the most illustrious and successful physical sciences – an attempt that, in our professional field, can lead to blunders. (Hayek, 2014: 595)

The fundamental difference between economics and the natural sciences then would be the fact that the complex events studied by this first area of knowledge could not be explained using simply quantitative or qualitative data (Hayek, 2014: 596). Such a problem resides in the fact that the structures which the social sciences investigate are complex. In other words, they are structures “whose characteristic properties can only be displayed through models composed of a relatively large number of variables” (Hayek, 2014: 597). In turn, such variables, in their absurd amount, could not be completely apprehended only through the use of statistics or participant observation, for example. Information is drawn from individuals’ logic and everyday experience; therefore, it could not be understood by an analysis of society. Thus, the author continues:

In explaining the functioning of such structures, we cannot, for that reason, replace information about individual elements by statistical information; if, however, we want to extract specific predictions about individual events from our theory, we must demand complete information about each element. Without this specific information about the individual elements, we will be confined to what I elsewhere called mere “pattern predictions” – predictions about some of the general attributes of the structures that will form, but be devoid of any specific statements about the individual elements that will make them up. (Hayek, 2014: 598).

For Hayek, knowledge is, in itself, limited. Statistics cannot create perfect models as in the natural sciences. We must recognize the limits that knowledge provides us. Moreover, it must be recognized that we cannot control order: we must accept it and live in harmony with it.[3]

The recognition of the insurmountable limits of knowledge should, in fact, teach the student of society a lesson of humility that should prevent him from becoming an accomplice in the fatal struggle of men for the control of society. (Hayek, 2014: 603).

At this point, we’ll begin to show differences between the defense of an a priori science and an a posteriori science. In other words, Hayek’s way of understanding how the social sciences work leads us to believe that he conceived the price system as an entity capable of being understood only through rationality, prior to empirical experience of a social nature. This way of conceiving epistemology—the valid way of obtaining knowledge—does not find a parallel in any of the classics of sociology.

In The German Ideology (2007), Marx criticizes the excessive use of metaphysical observations to the detriment of perceptions of material reality. His charge that German ideology was “upside down” demonstrates a crucial fact about his analysis of the social world.[4] This is because the author believed that German philosophy had placed ideas and representations of reality above material reality itself, causing us to have a distorted view. A kind of illusion emerges that ideas rule the material world, when in fact, we should realize the opposite. Material reality creates representations and exercises a deterministic function over them, a thesis which can be found throughout Marx’s work.

Even when the author in theory does not make use of calculations, he performs extensive historical studies that aim at understanding society itself. Suffice it to cite as an example his work The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. In this incredible study on the rise of Napoleon III, Marx seeks to understand how his conception of class struggle works in a case of conjuncture analysis. For this, the author mobilizes historical data, documents and secondary sources. It is significant to note that Marx also adds the category lumpenproletariat, an overexploited form of the proletariat. With this, the author brings his categories closer to empirical reality.

Therefore, this way of thinking presented by Marx and Durkheim separates them from Hayek, in opposite directions. We will give one last example, that of Max Weber. In the opening chapters of Economy and Society Volume I, the author examines the methodological foundations of his proposed sociological theory. For Weber, the sociologist would be the one who would interpret the meaning of the social actions of individuals (Weber, 2000: 4). Sense, on the other hand, is an orientation towards the other: we would only be able to capture it through observation of everyday life or historical examples. However, it is necessary to note that Weber makes an effort to understand the social meaning of actions, that is, the way in which individuals try to express meaning to the other in their everyday actions.

Even though Weber coined the concept of the ideal type, it does not escape empirical observation of the social world. This is because the ideal type is a generalization, an abstraction, which is only constructed through extensive observation of reality; for him, we should distance ourselves from any value judgment that is not constructed from empirical reality (Weber, 1992: 21). If we turn to his celebrated monograph The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (2004), we can observe Weber’s way of thinking in a more exemplified way. The author’s central thesis is that the Protestant ethic led to the emergence of the spirit of capitalism, through an undirected and uncontrolled social process.

To arrive at such an understanding, Weber promotes a wide statistical study about the religious affiliations of individuals in different countries, highlighting the correlation between the presence of Protestant segments and countries in consolidated stages of capitalism. However, Weber goes beyond this. The book promotes a systematic historical study which seeks the foundations of Protestant ethics, demonstrating that the moral perpetrated by Calvin’s Protestant segment provides the basis for capital accumulation necessary for the formation of capitalism. In any case, this extensive observation by Weber could never be carried out only through a priori reasoning or by only taking into account the figure of the individual.

With these brief examples, we highlight what, for us, seems to be one of the main disjunctions between sociological thought and Hayekian thought. This first contradiction is of an epistemological nature. Now, we will follow a second contradiction, exploring the way in which Hayek sees the being of the individual versus society.

For this, we will observe Wendy Brown’s book In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: the rise of antidemocratic politics in the West (2019). One of the author’s main theses is that neoliberalism “demonizes the status of society and politics” (Brown, 2019: 7). By this, the author means that for neoliberals, the idea of society, a structure formed by the interconnections of individuals, is strongly rejected. The first core idea of neoliberalism is that there is an order that should be a global project. In such a project, sovereignty, mainly the autonomy of decisions about the economy, should be dethroned and replaced by a general global law that would meet the demands of international agencies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

As we tried to demonstrate earlier, this price order produced by the markets, despite being spontaneous in Hayek’s view, must be sustained and even reinforced if it is endangered. This new way of thinking about the economy, therefore, gives rise to a new form of governance and understanding of the role of the State in people’s daily lives. Therefore, by this logic, the State must reconsider the social issue, which also leads us to question the role of democracy (Brown, 2019: 27).

This apparent deficiency of neoliberal thought is caused by its understanding of society itself. A fundamental question that we should ask ourselves at this moment is just what society is for Hayek and for the neoliberals. It is known that, for sociology, society is more than family and individual groups: it involves a complex structure of interdependence relationships. According to Brown:

The existence of society and the idea of the social—its ineligibility, its capacity for power stratification, and above all, its appropriation as a locus of justice and common welfare—is precisely what neoliberalism sets out to conceptually destroy, normatively and practically. Denounced as meaningless by Hayek and declared non-existent by Thatcher, society is a pejorative term for law in the present day. (Brown, 2019: 28)

For Hayek, it is not simply a question of the non-existence of society. The question goes beyond its philosophical bases. For him, the conception of society is a semantic fraud and a kind of crime, therefore relaying consequences which affect the lives of individuals. Worrying about the social is a form of tyranny, of controlling impulses and preferences; in these terms, due to the multiplicity of individual wills, there is not, and could not be, the formation of a consensus on how to reach the common good (Brown, 2019: 30).

The only possibility of cooperation that is not artificial is that made by moral traditions and market systems. These two bases for supposed collaboration between people are, in his conception, spontaneous and cannot be generated by the State or by a democratic will. This is because, as we saw earlier, Hayek believes that human knowledge is limited, incapable of producing models that can modify the order of markets. Thus, any attempt to create a planned and administered order by a state bureaucracy tends to become the result of tyranny.

From this point, we can derive more information from Hayekian thought. According to Brown, if something like society, social structures, or social groups don’t exist, just families and markets, there are also no social hierarchies (Brown, 2019: 40). Thus, we get the conclusion that power structures created from social relations such as gender, race, and class are artificial illusions created by the mismanagement of bureaucracy. Any income redistribution policy, creation of affirmative actions or gender equality, will be responsible for taking the population further away from the general order itself; and, therefore towards tyranny and inequality.

Finally, we find two fundamental contradictions between sociological thinking, located mainly in the classics, and neoliberal thinking, advocated by Hayek. The first one is epistemological. A fundamental hallmark of Hayekian thought is the use of rationality in a “pure” way, without any kind of empirical observation, mainly of a quantitative nature, whereas sociology differentiates itself by presenting an a posteriori reason. By this, we mean that it is necessary, in order to arrive at certain theses, to build a thought that is both abstract and concrete, and for this, it is essential to analyze historical and statistical data or to carry out participant observations.

A second problem, perhaps more contradictory than the first, is the difference in the conception of what society is. In all three classics of sociology that we cited—Marx, Durkheim and Weber—we find ways of conceiving society that consider structures and connections of interdependence which lead to coercive forms on individual behavior. For Hayek, there is no society, or at least, there shouldn’t be a society. There is only tyranny governed by public administration. To make this second contradiction even more evident, we will explore the question of what sociological-type thinking is.

What is sociological thinking?

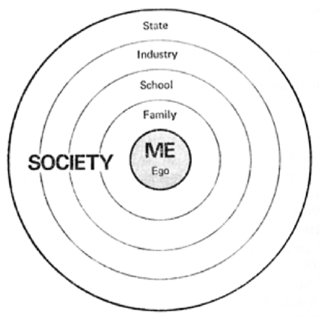

Norbert Elias was a renowned sociologist, known for works such as The Civilizing Process (1939), The Court Society (1969), and The Society of Individuals (1987). Although these works demonstrate knowledge about sociology that is fundamental for any individual who wants to delve into the area, we chose to approach a work in which the author dedicates his knowledge to explaining what sociology would be. In his book What is Sociology? (1978), Elias answers that society is a formation between the self and the other, in a web of interdependent relationships (Elias, 1978: 12). However, common sense makes us think that our ego (self) is disconnected from relationships with the world. Society, in this view, would be the structures and institutions which would not have a direct correlation in the formation of the individual. We think that we are not affected by, nor generated by, such structures. The figure below represents the common sense way of thinking:

On the other hand, sociological thought conceives the relationship between individual and society as a co-production, where both affect each other. For Elias, individuals both form and at the same time are formed by webs of interdependent relationships and figurations of various kinds with specific power structures (1978: 14). Such figurations can be families, schools, cities and social strata. In turn, such forms of grouping give meaning to the self, assist its creation and formation. Therefore, by articulating that “to understand what sociology is about, one must be aware of the self as a human being among other human beings” (Elias, 1974: 14), Elias reaffirms that it is only possible to understand the individual in one’s own setting.

It is important to emphasize in Elias’ thinking that social forces, the coercive capacity of society, are forces of individuals over other individuals. The German author demystifies the understanding of society by defining it as a society of individuals. In other words, society is understood to be made together by individuals, forming structures and balances of power. As the author says,

The tasks of sociology therefore include not only examination and interpretation of specific compelling forces to which people are exposed in their particular empirically observable societies and groups, but also the freeing of speech and thought about such forces from their links with earlier heteronomous models. In place of words and concepts bearing the mark of their origin in magicomythical ideas or in natural science, sociology must gradually develop others which do better justice to the peculiarities of human social figures. (Elias, 1978: 17)

Finally, it is still sociology’s task to demystify images that individuals are somehow cut off from their connections with others. However, Elias believed that such a form of sociological understanding was not fully developed in his time. This is because the metaphors used to explain the forces exerted by individuals on others, through configuration structures, were not translated into a completely adequate language for the human sciences.

According to the sociologist, when we think of social structures we build vocabularies associated with material, tangible things, independent or partially independent of individuals[5] (Elias, 1974: 19). When such a way of thinking was embodied by individuals, they believed themselves to be in opposition to society: society then was understood as an obstacle to individual action. This ethnocentric and egocentric view gives rise to what the author called social anxiety.

After this brief introduction, let us return again to Hayek’s thinking. As Elias predicted, Hayek understands society as a form of obstacle to individual action, a form of tyranny that takes away his freedom. The Austrian author fails to understand that such social configurations, networks of interdependence, actually constitute individuals. It is through the socialization process, through one’s insertion into the complex division of labor, that the human being acquires the status of individual in modernity.

If we explore Elias’ argument in more depth in The Society of Individuals, we come across the fact that the construction and understanding of the figure of the individual in classical liberalism is the result of a specific historical moment. In the Middle Ages, the understanding of the individual went hand in hand with his insertion in the community: it was not possible to have a vision of the individual being as a separate particle of the whole and that was capable of acting on the latter.

We should now better understand the difference between the neoliberal conception of society and the individual, and the sociological understanding of this same pair. For the first, there is no society, merely individuals and morals. Such collectives of people follow a natural order supposedly prescribed in their unconscious and which they will not be able to modify. For sociology, society is composed of configurations, structures, formed by individuals and that exercise coercive powers over them through balances of powers. The individual being is the result of such configurations; his understanding of himself and the world are produced within such arrangements. We will now explore this question through the eyes of C. Wright Mills.

C. Wright Mills was an American sociologist who taught at Columbia University. Mills is remembered for his works The Power Elite (1956), The Marxists (1962), and White Collar (1951). However, as we explored with Elias, we will dwell on a work in which the author makes an effort to understand the meaning of sociology; or, rather, in which the author tries to understand what would be a sociological thought in opposition to the thoughts of other sciences. This book is The Sociological Imagination (1959). Like Elias, Mills begins by warning that individuals feel trapped by snares and structures that go beyond their capacity for action (2000: 3). Individuals feel as if they are trapped in the orbits of their private lives.

Mills’ objective, with the term sociological imagination, is precisely to offer individuals an understanding capable of exploring the connections between their private lives and the society (orbits) that surround them (Mills, 2000: 5). Unlike Hayek, Mills invites us to think of the individual as a product of a given time and space. In other words, the sociological imagination connects the individual trajectory and its relations with the society in which it is inserted. For the American author, if the individual understands the transformations that take place in society, he is able to understand how these can affect his own private life.[6]

Like Elias, Mills foresaw that individuals felt touched by dark forces which they could neither define nor find their origins. Such coercive movement caused estrangement from the world and, in turn, made them feel constitutively in opposition to society (Mills, 2000: 13). However, for the North American author, such forces are the consequences of the political techniques of domination that act through social relations.

At this point, it is necessary to point out that Mills was terminally against an idea of human nature. For the author, every individual is a form of product of his values. Such values in turn were constructed through a culture which was compiled through an historical and geographical process. If we return to Hayek’s thought, we will see that this author believes that there is a human nature, independent of an historical construction. Therefore, there is an incompatibility between Mills’ socially constructed individual and Hayek’s individual moved by an immutable unconscious.

Final Considerations

To conclude, it is valid to return to our objective. Our primary intention was to present two thoughts that, in our view, are distinct. The first of these is neoliberal and the second is sociological. As a limitation to our work, we understand that Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig Von Mises are not the only authors who compose the neoliberal way of thinking. Although such intellectuals have played a role of great relevance and have been recognized by international awards, there are still other authors who have their own vicissitudes. One of these names is of course Milton Friedman, winner of the 1976 economics prize. Unlike the others, Friedman foresaw the use of quantitative and statistical data for macroeconomic models.

We could apply this same limitation to sociological thinking. We dealt with classic authors such as Karl Marx, Max Weber and Émile Durkheim; and, in a second moment, we deepened our considerations about what sociology is through Norbert Elias and C. Wright Mills. With this, we still fail to address other classic authors such as Georg Simmel, Gabriel Tarde and Herbert Spencer. We also do not deal with modern authors of great impact for sociology such as Anthony Giddens, Pierre Bourdieu and Jurgen Habermas. To justify this omission, we believe that the authors presented are the most fundamental for building the foundations of sociological thought. And, from the manuals of Mills and Elias, such fundamentals become more organized and clear.

Despite these imperfections and inconsistencies, we believe that our hypothesis about these ways of thinking holds. There were two fundamental contradictions that we detected in our comparisons. The first of these was of an epistemological nature. By this term we understand the valid way of obtaining knowledge. For Hayek, the valid way for obtaining knowledge seems to reside in rationality, which does not necessarily depend on empirical experience. For him, even quantitative data are not capable of modifying human nature which, at its roots, is only understandable from an a priori mental exercise. For sociologists, empirical observation is the most important feature of their analyses. All the thinkers in this field presented and utilized empirical data, whether historical or statistical, to build their models and abstractions.

The last difference is what we call ontological. With this, we understand the way of understanding about the individual being, its formation and genesis. For neoliberals, beings appear in opposition to the social world. The social world, an unreal abstraction created by men, takes away freedom from individual action. In this case, there is no society, no power relations, just individuals with their morals and nature. For sociology, on the other hand, society is constructed and constitutes the individual. Being, as we should understand it, and concomitantly epistemology, only have their purpose within a specific historical, social and geographic arrangement.

Notes

[1] Order is defined as: “a new international economic order was a signal—a vast space of information transmitted in prices and laws” (Slobodian, 2018: 224).

[2] To view the speech in full, visit: https://www.revistamises.org.br/misesjournal/article/download/691/385/. Last accessed on December 15, 2020.

[3] Just to reinforce our hypothesis, we compare again the role that quantitative data has for Durkheim and for Hayek. In Suicide (2000), Durkheim states that one of the ways to understand the relationship between suicide and society is through the social rate of suicide. This rate, in turn, was detected using statistical data. Without these, we would not be able to compare deaths by time or space. The French author, unlike the Austrian, had full confidence in the use of statistics as a research tool.

[4] For an explanation by Marx himself, we suggest the following sentence: “The representations that these individuals produce are representations, whether about their relationship with nature, whether about their relationships with each other or about their own natural condition [Beschaffenheit]. It is clear that, in all these cases, these representations are a conscious expression – real or illusory – of their true relationships and activities, their production, their exchange, their social and political organization. The contrary supposition would only be possible if, in addition to the spirit of real and materially conditioned individuals, a separate spirit was assumed. If the conscious expression of the actual relationships of these individuals is illusory, if in their representations they turn their reality upside down, this is a consequence of their limited mode of material activity and their limited social relations that derive from it” (Marx, 2007: 93).

[5] “No matter how painfully aware we are of their inadequacy, more adequate means of thought and communication are in many instances simply not available at the present” (Elias, 1978: 20).

[6] According to Mills: “to be aware of the idea of social structure and to use it with sensibility is to be capable of tracing such linkages among a great variety of milieux. To be able to do that is to possess the sociological imagination” (Mills, 2000: 11).

References

BROWN, Wendy. In the Ruins of Neoliberalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

DURKHEIM, Emile. The Rules of Sociological Method. Lisbon: Presence, 2004.

DURKHEIM, Emile. Suicide: Study of Sociology. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2000.

ELIAS, Norbert. What is Sociology? Juventa Verlag: Columbia University Press, 1978.

MARX, Karl. The German Ideology. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2007.

MILLS, C. Wright. The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

SCHEUERMAN, W. E. The Unholy Alliance of Carl Schmitt and Friedrich A. Hayek. Constellations, 4(2), 172–188. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00047

SLOBODIAN, Quinn. Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

VARES, Sidnei Ferreira de. Sociologism and Individualism in Émile Durkheim. Crh notebook, [S.L.], v. 24, n. 62, p. 435-446, aug. 2011. Fap UNIFESP (SciELO).http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0103-49792011000200013

VON HAYEK, Friedrich August. The Pretense of Knowledge. Stakes: Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, Law and Economics, [S.L.], v. 2, no. 2, p. 595-603, Dec. 2014.

VON MISES, Ludwig. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. São Francisco: Fox And Wilkes, 1996.

WEBER, M. “The ‘Objectivity’ of Knowledge in Social Science and Politics”, pp. 107-117 and 124-133 in Social Science Methodology (Part 2). Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, 1992.

WEBER, M. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Sao Paulo: Company of letters, 2004.

WEBER, M. “Fundamental Sociological Concepts”, in Economy and Society, vol. 1, pp. 3-35. Brasília: UNB, 2000.