Abstract: This is a description and an exploration of current cosmopolitical orientations concerning two major events – the enterprise of human knowledge and the development of capital. The cosmopolitical orientations – the cosmopolitical parties – are shown to be orthogonal to usual macropolitical orientations – left and right. Coalitions between these parties are challenging but some alliances are described and a new way to bring together the left of two of these parties is proposed.

Keywords: inhumanism, animism, capital, nihilism, cosmopolitics, Marxism.

There is no spirit without a machine,

the appearance of spirit is a machine which colonizes the organism,

the victory of spirit over mere life

appears as a “regression” of life to a mechanism.

– Slavoj Žižek (Less Than Nothing, 483-4)

In the last days of humanity, everything

should be approached from a cosmic point of view.

– Karl Kraus

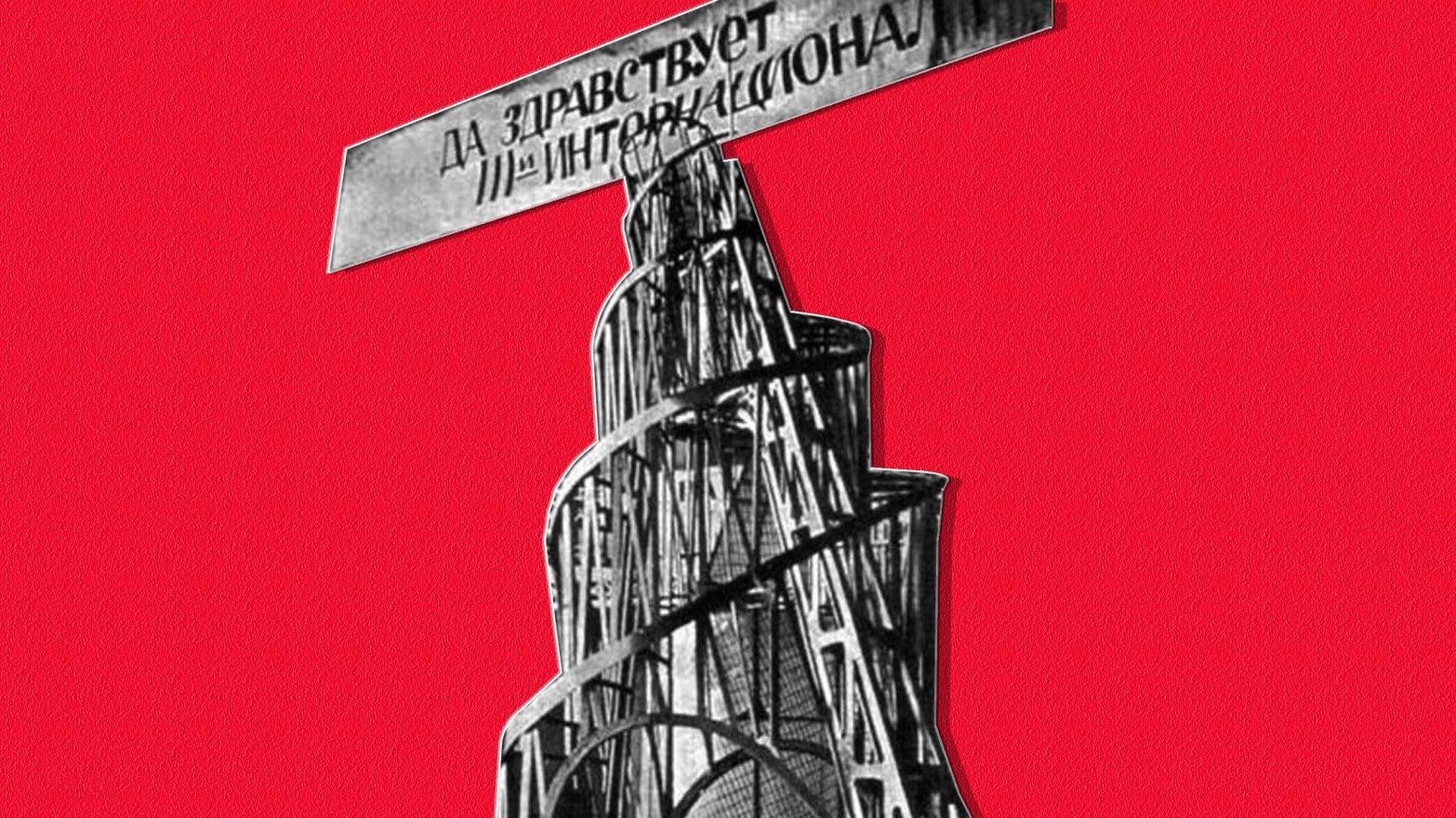

1. The cosmopolitical arena

Commenting on Karl Kraus’ motto that even the most ordinary event should be approached from a cosmic point of view, Fabián Ludueña claims that what is needed is to both investigate the cosmos in order to explain human politics and to resort to the (bygone) human world to understand each aspect of the cosmos.[1] Cosmopolitics emerges then as the intertwined attention to the increasing cosmic nature of human political concoctions and the growing cosmic impact of human political decisions. Facing the covid19 pandemics, for example, humans find themselves divided between those who recommend persistence in building a controlled and artificial replacement for the tricky natural environment and those that would rather see a renewed alliance with the Earthly agents from which we were once upon a time inextricably connected. The dispute has many faces and nuances – it is, roughly speaking, a dispute of two cosmopolitical parties, even though each of them has several different and even conflicting tendencies.

Cosmopolitics is about the societies of agents in the cosmos that are involved and affected by human political decisions. Decisions, to be sure, are to be taken not as deliberate courses of action based on reasoned choices, but rather as consequences of non-transparent factors when a particular road was chosen. Garrett Hardin once said that the science of ecology is founded on this generalization: We can never do merely one thing.[2] So is cosmopolitics. Like ecology, it is not a human endeavor in the sense that it is staged by humans, but at least the elements of it that will interest us here are also staged in humans. Accordingly, human action can alter the cosmopolitical course of events – but we can never do merely one thing.

Clearly cosmopolitical is the great extinction of species we are witnessing, the enormous changes in the population distribution of microorganisms due to the destruction of their usual habitat, the anthropic climate change, the insertion of satellites in the orbit of the Earth, the Anthropocene. There are many attitudes that humans can choose to have concerning each of these issues – including denying that they are indeed taking place or that they are a matter of concern. There are, nonetheless, other remarkable cosmopolitical events that are arguably decisive even if they could seem prima facie less salient. Two of them are particularly relevant in shaping the current cosmopolitical landscape.

The first one is what was often dealt with by Nietzsche since the opening words of his On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense: “Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing.”[3] This was, according to Nietzsche, a moment both daring and hypocritical. Knowledge, in the Western metaphysical endeavor that started with Aristotle from the grounding gestures of Plato, has an enormous impact on how things take place everywhere it reaches. Heidegger read Nietzsche as shaping the idea of nihilism to make explicit a cosmic plot in the saga of metaphysics – it unveils itself as a slow coup d’état in the order of things.[4] The drive is to seize their command; the direction is a universe in standing reserve that becomes thus fully controllable. That death of God gives rise to a cosmopolitical era – an era in the history of being (or of Seyn)[5] as Heidegger would put it – that could be called the age of danger when everything is being persecuted in order to have its intelligibility extracted and their matter made replicable and redundant.[6] The persecution, to be sure, cannot stop anywhere short of human bodies and human agency. If the drive of nihilism takes its course – and commands are all seized – it would give rise to a different epoch where power is fully up for grabs. This is what Heidegger understood as being Nietzsche’s bet: the last man will be overcome towards a fully consummated, completed nihilism. Against this last metaphysician, Heidegger would rather advocate a turning back from this metaphysical saga – we could perhaps look for a turning point back to a point where intelligence went astray into the age of danger. That turning point – the Kehre[7] – would involve somehow a new beginning that humans cannot bring about but can prepare. These two attitudes towards nihilism and the saga of metaphysics – and the ecology of practices that prevails among the Moderns[8] – determine two contrasting policies that, to be sure, admit several important nuances. The two alternative policies: either trust the flow and hope the upheaval will eventually lead to a desirable (cosmopolitical) state or attempt at resist the flow and look for some kind of Kehre that would take things back – perhaps to a past that was never fully actualized but that contrasts with the current times and its prospects. The two alternatives understand current (cosmopolitical) times in opposite ways; while the latter takes the age of danger as catastrophic, the former understands it as being anastrophic. A catastrophic time is one that destroys the past – somehow to be cherished – whereas an anastrophic time is one that prepares the future – somehow to be welcome.

The second remarkable cosmopolitical event is best described by a tradition that starts with Marx: the power of capital that dismantles, erodes, deterritorializes and melts existing codes and practices. Capital is perhaps as exterior to the human as knowledge in its metaphysical drift but it is not clear if anything has ever been originally human. Capital is a cosmic force that inhabits humans – like nihilism, it is staged in humans. Deleuze and Guattari remark that capital is the nightmare of any socius; it is a possible future that would erode any social connection.[9] Nick Land famously described it as “an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy’s resources.”[10] No matter its origins, capital has a remarkable effect on the planet and eventually beyond it; its drive is to make things into merchandise and associate a price to each of them. Its epoch is the age of commodification that gradually also encompasses human bodies and human agency. In fact, capital and knowledge – commodification and danger – have much in common apart from their (partial) simultaneity: capital also makes things replaceable, paves the way towards a greater abstraction – makes labor itself abstract[11] – while exorcizing fixity, it interferes with the existing associations because, as the nightmare of any socius, it has a de facto special license to care about nothing else. The two cosmopolitical events are to an important extent related; the nature of that relation is nonetheless much debated. Perhaps capital was a development internal to the very age of danger, perhaps nihilism is the commodification of things in embryo. In any case, it seems clear that we cannot mobilize any one of the two to fight against or sweep away the other. They certainly feed each other even if they had different pedigree and only casually converged. Their convergence itself had a great impact on everything else – especially because together they poised the Moderns to the colonial projects that became their trademark.[12] The epoch of capital can also be considered in two alternative ways: either as the flow of melting and dismantling that cleanses what it touches preparing for a brighter future or as a disaster that uprooted whatever was in the right place and needs to be reversed or extinguished. Clearly, both the view of capital as remedy and as poison come in different flavors. However here again there is a catastrophic and an anastrophic view of the event: one that is grounded in the past – perhaps the non-realized past that seemed promising and fruitful – and the other grounded on what has been made possible – or inevitable – by the current cosmopolitical state. As with the age of danger, the attachment to the past could be tracking a specter, a past future that was left undeveloped. Capital can be reactionary because it dispelled what was looming on the horizon before it – it was then a retro futuristic catastrophe. Federici has been espousing a hauntological view of the capital catastrophe according to which the communal future sprouting at the end of the feudal times was one of the main targets of transformation brought about by the age of the commodities.[13]

Anastrophe, catastrophe, hauntology, and retrofuturism show how cosmopolitics inhabits an arena where future and past are equally up for grabs. The two events associated with nihilism and capital shape the future while unveiling in the past a forest of unexpected roots. To be sure, it is the future that is at stake but it carries the specters of what was never actualized. Macropolitical choice is often commensurate to mandates or to a human lifespan and, to the extent that it could be notionally separated from the cosmopolitical dispute, its events take place in a background of things remaining otherwise the same. In contrast, because to a great extent it deals with pharmakon more than with definite outcomes, it is impossible in cosmopolitics to do merely one thing.[14] Cosmopolitical time is a political instant charged with spells of cosmic duration. The very events that gave rise to the age of danger and the age of commodities increasingly expose human political life to the cosmic elements.

2. The cosmopolitical parties

If the divides brought about by the two cosmopolitical events above determine what we can call cosmopolitical parties that are chiefly constituted around recommendations concerning furthering or reversing those events. They can be parties concerning the age of danger or the age of commodities and they can be in both cases anastrophic or catastrophic.

2.1 Nihilism

Concerning nihilism, we can find at least two contrasting parties: one that trusts it should be promoted and, at least to a great extent, intensified – the anastrophic party – and one that would rather recommend its reversal or exorcism – the catastrophic party. There could be little alliance or common cause between the two parties taken separately. If however, we considered them together with other cosmopolitical parties and macropolitical attitudes, a landscape of transversal dialogues could be possible.

2.1.1 The anastrophic party (N-AP)

Facing nihilism, an anastrophic party recommends embracing the flow guided by an unconstrained quest for further knowledge leading to an unconstrained right to transform existing processes into controllable procedures. The transformation of the world into a set of devices under control paves the way for an increasingly controlled environment where the commands are available and nothing is triggered by an unreachable force. Nietzsche, in The Gay Science, tells the story of a madman who goes to the market and claims that God is dead and the deed was ours.[15] The assertion entails that we have drunk the sea, erased the horizon line and detached the Earth from its Sun. This is the program of nihilism in great strokes: to undo physical necessity by learning how to pull the strings. The cosmopolitical impact of the project is that of seizing the command and Nietzsche pictures it as what renders explicit the will to power. Once the forces of nature are controllable, the remaining issue is who is going to press the button. Nihilism is complete when no force is out of the reach of a dispute for power – it somehow transforms cosmopolitics into a macropolitical dispute where humans are not necessarily the only disputing agents. It becomes the continuation of politics by other, cosmic means. The party willing to embrace nihilism holds that it is all for the best – power will be distributed and once God is dead a monarchy will be replaced by something like a sound (cosmic) democracy where no power is beyond the agent’s hands. The killing of God, as Heidegger emphasizes, is the exorcism of anything transcending.[16] It promotes immanence – an order where nothing affects things from outside, where there is no outside.[17] The cosmopolitical import of furthering nihilism is the transformation of the world into an arena for power struggle. This cosmopolitical party is the one that recommends it – it favors a regime where the cosmic becomes a political dispute for power over each existent.

This cosmopolitical party, like most parties, harbor different tendencies inside it. The Nietzschean trend is perhaps the orthodox one that explicitly claims that power struggle should be unconstrained and the immanent democracy of free spirits that will follow the death of the transcendent monarch will be a regime where things will be decided in terms of the will to power. This tendency would hardly impose restrictions over power struggle: let an unabashed democratic game decide how things become, no (transcending) rules should interfere. This tendency – which is orthodox in the sense that it explicitly proclaims what the party makes possible – commands few explicit adherents. Most supporters of the party would rather mix the welcoming of a controllable cosmos with either a belief in humanity or in reason. To be sure, the Enlightenment tendency inside the party, which certainly had its heydays, has no longer the majority, at least in the open. This is because it became less plausible to believe both in humanity and in reason to temper the (cosmic) power struggles. The seizing of the commands of the world entails seizing the commands within humanity. Humanity is not immune from nihilism and if it is best to trust nihilism to lead things closer to its logical conclusion, the belief in humanity could seem out of place. Further, the mere belief in humanity is often at odds with the belief in reason. On the other hand, a belief in reason is often challenged by human biases that should not be left unexamined and uncontrolled if the course of nihilism is to be trusted. A recent tendency emerged from the difficulties of humanism within the credo of the party is inhumanism.[18] The basic idea is to trust intelligence as what drives the extraction of the intelligibility of things and hold that its deterritorialized force will not only correct itself indefinitely but also wash out human biases composing a Geist that is free from any natural constraint.[19] Here the inspiration is less from Nietzsche’s free spirits that detach themselves from any root or territorial connection and more from Hegel’s Geist that struggles to overcome any natural constraint. The inhumanist tendency makes explicit how the process of extracting the intelligibility of natural processes feeds into the very notion of intelligence and that permanent revision is constitutive of Geist. There is no attachment of Geist to the humans – neither to the now existing humans nor to any mutated population that artificiality will forge. Geist is a constant transformation guided by an exorcism of what is natural that will not stop short of the human; artificial intelligences are gestated by Geist in the context of the endeavor of extracting the intelligibility of things making them replicable.

Inhumanism has no problems holding that artificial intelligences will respond to Geist and will be moved by it in the context of a controllable cosmos. To be sure, the inhumanist tendency rejects the idea that anything could have its control seized by anything else because the will to power is tempered by Geist and the immanent democratic game is guided by the immanent norms instituted and applied by Geist. The inhumanist tendency can bill itself as an aggiornamento of the Enlightenment tendency: in a post-human environment, we can still believe reason will have enough strength to curb other forces guided by nothing but the will to power.

2.1.1 The catastrophic party (N-CP)

In contrast with the anastrophic party, the catastrophic party concerning nihilism holds that it would best be reversed or brushed aside. Heidegger understood Nietzsche as moving inside the realm of metaphysics – the realm of nihilism – and proposed that we should rather exorcise this realm altogether. His Kehre intended to explore the beginnings of the process that led to nihilism to make sure that we can redirect thinking towards something else. He claims that the separation of intelligence from physis, from the force that makes things act as they do, was a decisive movement towards an ecology of practices that exposes things while making them redundant. That ecology of practices is what promotes the age of danger. The Kehre then would have to look for something underlying the separation between intelligence and physis and Heidegger puts this in terms of preparing for a new beginning, a beginning that is faithful to letting events come through and letting things present themselves of their own accord. The party of reversal aims at undoing the cosmic advances at controlling things. It is a cosmopolitical party that attempts to overturn the nihilist past, to reverse it, to promote some kind of Kehre. The attitude is not necessarily that of a simple restoration; although nihilism has been regressive, it is not enough to go back to the cosmological status quo ante because we risk stepping back into the same pitfalls if the drive towards metaphysics is not definitely put aside and replaced by something else. What is at stake is the very connection between thought and world to prepare a replacement of the existing ecology of epistemic practices by a different way of engaging the intellect with its surroundings.

The catastrophic party concerning nihilism also harbors several tendencies. The Heideggerian tendency focuses on looking for new beginnings within the scope of Western thought: philosophy should move away from its metaphysical past and embrace a different kind of thinking based on what was left undeveloped from its inception. The inspiration is the kind of cosmic engagement the pre-Socratic philosophers attained before intelligence (nous and logos) was detached from physis.[20] The program of this tendency is to foster ways in which a different set of practices of thinking inscribed in the pre-history of nihilism can prove to prepare a Kehre. Other tendencies have been developed in recent years looking at different ecologies of practice, based on non-modern and non-Western engagement with the non-human. A possible departure from the Heideggerian tendency is to stress that the alternative to metaphysics could be found in the mythical that Heidegger dismisses by arguing that thought was then too connected to everything else to engage in a proper sense of its existence.[21] Heidegger embraces a form of humanism according to which, basically through language, humans have special capacities that them out of the rest of the world – and the mythical alternatives are insufficiently faithful to that special condition. Different tendencies within the party would contrast this humanism with some sort of animism criticizing the Heideggerian tendency for not paying enough attention to what is outside the Western traditions because of an attachment to the exceptional character of the human.[22]

The animist tendencies would rather invoke the capacities of the non-human to make alliances, engage in treaties, perform diplomatic acts and be part of economies of gift, exchange, and predation.[23] The idea is to firmly insert human agency in an environment of other agents around in a way that the non-human is not what primarily can have its intelligibility extracted and its movements controlled. More attention should be paid to the bodily connections between human experience and the environment around them – an experience that is not directed towards an image of the world but rather an association between humans and non-humans. Instead of considering the human population, the animist tendencies call for an engagement with the Earthbound (Latour), with multispecies kinship (Haraway), or with an otherwise multifaceted ecology of practices (Stengers).[24] Animism is perhaps an inconvenient label as often party tendencies are – it seems often too broad and sometimes too narrow. What matters most in these tendencies is the attempt to establish new epistemic practices by redescribing some well-known ones and by discovering epistemic practices – even inside Western science – that cannot be appropriately explained by the prevalent idea concerning knowledge. The general idea is to make sure agency is somehow distributed and not only an exceptional human endowment that bifurcates what is looking for command and what is destined to be commanded. Amerindian perspectivism would further hold that the “humans” and “predators” are positions to be taken as deictic, a human in the forest can become a prey to the jaguars who would then be a human hunting its meal. Contact with the non-human is always dangerous and delicate – thought is needed to make sure convenient and respectful deals are crafted on each occasion. The perspectivist tendency would advocate that kind of respect grounded in the instability and vulnerability of the human whose perspective cannot aspire to be neither a view from nowhere nor the only valid point of view.[25] The idea is that a world of points of view precludes the efforts of reason to capture the unequivocal intelligibility of anything. The shamanic point of view is that on a different time scale, depredation of the non-humans would have consequences beyond human history; consequences like climate change, the Anthropocene, the extinction of crucial species etc. Another tendency in the party is the gerontology recommended by Povinelli.[26] It charges the animists with a left-over of nihilism for the distinction between those that could use resources and the resources themselves is still implicitly operative and is part of the carbon-based imaginary that fuels the age of danger. To fully abandon that distinction Povinelli recommends exorcizing the cleavage between what is alive and what is dead and, further, the living and the inert – and the biological and the geological. The geontological tendency engages with the lack of separation between the agent and the non-agent to make sure that nothing separates out once and for all the commanded and the command. Rather, the emphasis is on attention – thinking is about focus, about attraction, about directing one’s concentration somewhere. It is about lures for attention, and no cleavage determines their shape outside the cosmopolitical arena. The geontological tendencies are close to the animist ones in many issues; on the other hand, the biggest divide inside the catastrophic party has to do with the colonialism associated with the Western tradition.

2.2 Capital

Concerning the age of commodification, there are also at least two contrasting parties: one that believes there is no way backward and the capacity to dismantle traditions that capital has already displayed is to be embraced and perhaps guided towards the best direction – the anastrophic party – and one that would rather take capital to be thoroughly regressive and, as such, should be tamed, contained or fully removed from a prospective socius – the catastrophic party. Here again, taken in isolation, there could hardly be any coalition between the two. If considered together with macropolitical tendencies and other cosmopolitical parties – those concerning nihilism, for example – then opportunities for dialogue and convergence emerge.

2.2.1 The anastrophic party (C-AP)

The idea that capital has swept its path with transformations, melting traditions and changing privileges is well-known from Marx’s texts as much as from previous accounts of the wealth capitalist practices have brought about.[27] Capital laid the grounds for a remarkable change in the way humans relate to each other and to their surroundings. The anastrophic party is the one that somehow welcomes the event and recommends its strength to further change social (and cosmic) relations. The project is to use the force of capital to transform things, or rather to trust in its capacities to forge something different. The basic tenet of the party’s program is that capital is progressive and it wouldn’t be advisable (or tenable) to go against its flow – the adversaries of the party are seen as prey to a nostalgia for times that are ultimately not desirable. To reverse to the previous social relations would be a regressive movement to the local, to the narrow, to the unconnected and to decree universal mediocrity as Marx says quoting Pecqueur.[28] The risk of lapsing into mediocrity is what drives the anastrophic party away from the past and towards embracing whatever speedy reshuffling capital is promoting. It is a fast train going somewhere exciting – and as such, like with nihilism for Nietzsche and the other anastrophic party, it deserves our confidence. It is a process that could be painful and could look like a catastrophe but commands trust in the process. Marx sees capital as the pharmakon that will cure society of some of its greatest evils by bringing in a very different post-capitalist future. He compares this process with what Goethe writes of Timer: “Should this torture then torment us [s]ince it brings us greater pleasure? Were not through the rule of Timur [s]ouls devoured without measure?”[29] The pharmakon is the insertion of an alien element in the socius, an element that can change deeply entrenched practices in the form of traditions and hierarchies. The anastrophic party entrusts Capital to bring forth a better future that could not be possible without it.

Marxism is the most well-known tendency within the party – it is also a paradigm of the belief in the capital anastrophic capacities by putting forward a projection of the future that could be prima facie surprising. Capital brings about universal connection, industrialization, increased production, and an increasingly fast change in forces of production. It dismantles fixity and promotes mobility; faster flows that are less and less codified. Through those changes social relations are challenged and have to adapt. The flow of money drives a rush towards abstraction where production, labor and currency itself becomes easier to artificialization through machinery. The introduction of all sorts of machinery itself makes capital into a major cosmopolitical ingredient: machinery engaged in production congregates elements from different places and brings together people and labor from different backgrounds. The trust in what capital forges is the trust in production itself – its forces promote revolutions. Marxism is about the impact of production and its proletarian hero is precisely a universal agent of production. Deleuze and Guattari update that image of this hero with the figure of the schizo who is geared towards production alone – and sees registration and distribution as immanent to production.[30] Capital brings about the capitalists but also the proletarian, coupled to the machinery and effect of the nomadism required to produce, distribute, and register commodities. This is the anastrophe of Marx: capital is like an omen through which we can see a post-capitalist communist future. Capitalism acts like the tip of an iceberg from the future that touches the present to make sure the attachment to the local, the oppression mechanisms, the hierarchies and the social control through traditions is melted away to pave the way for something entirely other – other from capitalism itself. Deleuze and Guattari describe the work of capital in decoding the flows as a march towards further schizophrenia in the sense that production becomes ever more central in the socius while the psychotic elements like the original territory or the despot lose their grip on the economic life. The drive is towards faster flows and eventually capital accelerates beyond what capitalists can follow – the power of dismantling protects no one in particular. The forces that capital brings about will then eventually undo the structures that capital has thus far put in place. Capital is therefore only bound by further schizophrenia, by further production that is only possible through what it drives. It is perhaps the schizophrenia who ultimately places this alien intelligence in a position to erode the existing social structures. That connection between the schizophrenia of capital and the proletarian as the schizo forged by its march will dismantle the axiomatics of capital, the reterritorialization promoted by capital while melting the previously existing socius. The same schizo force that deterritorialized everything else will turn again the remnants of fixity that capitalism as such tries to preserve.

This anastrophic party has also several tendencies in dispute. One of them, in great contrast with the Marxist tendency is the unconditioned capitalist tendency. This tendency understands capital as bringing about not a post-capitalist or a communist future but an intensification of capitalism that could look very different from what we have seen this far. Land has argued that we have witnessed nothing, this far, but pre-capitalism.[31] The main idea is that capital is ever-changing and will sponsor no other revolution, but a continuation of a process that will free societies from fixed structures, hierarchies and the instruments of the human security system. At the same time, it will foster a more artificial environment where capital can exert its power with fewer constraints. The anastrophe considered by this tendency is rather the gradual elimination of the despotic elements of the state – rather by replacing it with market mechanisms or by inserting it within these market mechanisms. (The alternative is the one between libertarianism with its anarcho-capitalist credo and what Mencius Moldbug called neo-cameralism.[32]|) Unconditioned capitalism shares with the rest of the party the idea that we cannot but accelerate the flow of transformations put forward by capital, but rejects the image of the proletarian – or the schizo – as the ultimate conductor of the process of freeing production from any constrain. Rather, the assumption is that capital itself is a permanent artificial revolution and the very engine of criticism. Land emphasizes its artificial nature and its disconnection with human psychology – it is as if the future came to unsettle the human-centered history. This tendency is hardly compatible with most forms of humanism; it tends to hold that humans are not only less and less the protagonists of the economic transformations that capital fosters but also their security system is not a political ideal to be defended. Capital, according to these tendencies, forecasts a mature version of capitalism that will carry on melting the existing structures of the human socius.

2.2.1 The catastrophic party (C-CP)

In contrast, the catastrophic party holds that capital is thoroughly regressive. There is nothing revolutionary in its trajectory and it has worked most of the time to preserve and not to dismantle the existing status quo. The party holds that capital is either an agent of bad conservatism or it led the cohesion that makes societies survive and promote well-being astray. It brought conservatism in because even if it displaced some oppressive structures, it replaced them with further oppression, further hierarchy and greater constraints. It led social cohesion astray because it gave rise to connections between people based on their bought immunity to social responsibility and anonymity with respect to social recognition. In any case, the idea is that the effects of capital are best removed as they are most unwelcome. These effects should be rather substituted either by previously existing social relations – including social relations concocted and not realized before capital – or social relations that exist among non-colonized people untainted by the damage of capital. The party harbors different brands of nostalgia: for peasants, for collective lives rehearsed in the past, for indigenous communities, for traditions tied to soil and blood. In all those cases, there is something to be lamented about capitalist development and the program is overturning capital so that a different kind of socius is promoted.

The party has many conflicting tendencies. One of them is the commons tendency, promoted by Federici, Linebaugh, and others. This tendency sees capital clearly as more of a reterritorializing force than a melting catalyst. Federici argues that capitalism was a way to keep the powerful in place after the peasants revolts which experimented with different ways of organizing production, and distribution.[33] The peasant revolts took place in the background of the European commons of the 14th and 15th Century where land was available for peasants and the feudal grip on them was loosening. The commons were an attempt to be rid of private property of the land and to understand production as embedded in the workers’ community life. Capital destroyed that incipient post-feudal form of production making peasants in the commons into proletarians that have little ties with any community, traditional craft or non-human landscape. The commons tendency is somehow hauntological: it looks at the past to find something that was not fully actualized before been swept out of the way. It promotes not a simple nostalgia for feudalism or anything before capital, but rather concentrates on what could have flourished had it not been smashed by capital. What follows from these post-feudal commons were disastrous as the workers had all their environment plundered in exchange for a life of misery in anonymity. This decadence was just the prelude of the great catastrophe that uprooted workers into proletarians and brushed the commons out of the political imaginary. The catastrophe involved also the colonial enterprises around the world and the genocide of the witches that promoted an epistemicide as it replaced the situated practices of the peasants with their surrounding non-humans with an imposed conception of knowledge in line with nihilism and the age of danger. The killing of the witches replaced the communal practices with the knowledge-driven ones that systematically disempower women, the colonized peoples and the peasantry.[34] The commons tendency believed that only a restoration of the commons could undo the tragedy – and that could involve a return to some kind of locality. The drive towards internationalization that capital promoted ruined great parts of the planet and damaged some of its more entrenched dynamics. The drive towards less situated production exhausted workers, destroyed the autonomy of local economies and concentrated power. It didn’t work towards an emancipation of the oppression that existed in local communities but rather reinstated oppression in a more globally and anonymously. The drive towards global economic ties and more anonymity proved to be no more than a way to keep the worker at bay, no longer connecting with their chiefs and bosses but in the same regime of subservience. There is little point in getting rid of local hierarchies if we replace them with anonymous ones that destroy the community links and replace them for nothing better. Other tendencies within this party actively defend degrowth and a reversal to globalization to cope with the aftermath of the perceived catastrophe. Further, there are tendencies in the party that understand capital as fighting against the basic tenets of human life – communities, rituals, religion, contact with the soil and blood connections. There is a blood-and-soil tendency that aims at exorcizing capital with all its dismantling of the deeply entrenched traditions that are taken as originally human. This is another form of humanism, one that would take humans as being by themselves tied to an environment that sustains and gives meaning to their existence.

3. Cosmopolitical coalitions: the left

Coalitions among cosmopolitical parties are different from those among macropolitical ones. It is true that convergence could pave the way for some strategic alliances and that often parties combine forces to struggle against a common enemy. However, cosmopolitical coalitions cannot be oblivious to macropolitical divides while often the macropolitical coalitions can be indifferent to anything else. The trouble is that cosmopolitical parties are often deeply divided into macropolitical lines – that is, between left and right. This is clearly the case of all the four cosmopolitical parties considered here – N-AP, N-CP, C-AP, and C-CP; the inhumanist tendency of N-AP, the animist tendencies and other convergent tendencies within N-CP, the Marxist tendencies in C-AP and the commons tendency of C-CP lean to left and often find themselves in titanic struggles with other tendencies inside their own cosmopolitical parties. In fact, cosmopolitical coalitions are different because cosmopolitical parties are not macropolitical convergences. This is the drama of these parties and these coalitions – and a drama that springs from the very cosmopolitical principle that we can never do merely one thing.

Cosmopolitical alliances ought then to cut across party lines. But still a left coalition of tendencies, for example, is not straightforward – and this is because cosmopolitics gets on the way. Often different attitudes – the catastrophic and the anastrophic attitudes – towards a cosmopolitical event makes alliances challenging. The challenge is to assemble the left of different cosmopolitical parties in a way that macropolitics – and Realpolitik – can help bring together different opposing attitudes.

A seemingly easier step in this direction is to look for coalitions along the axis of attitudes concerning cosmopolitical events. Indeed, one can group tendencies in the two anastrophic parties and in the two catastrophic parties. We can think of inhumanists leaning towards Marxism and welcoming an anastrophic view of both nihilism and capital. This is indeed not far from the position held by Ray Brassier, JP Caron, and, arguably, of the late Mark Fisher.[35] Inhumanist Marxism claims that the revolutionary impetus brought up by capital associated with the idea, grounded in the age of danger, that most things exist to be resources for the human or post-human agents, is what could bring a future where machinery and technology, in general, will be the product of an intelligence which is capable of extracting the intelligibility of anything. Inhumanist Marxists would trust humans and post-humans are going to be emancipated by the course of a proletarian revolution that will carry the flag of nihilism. Formulated like this, inhumanist Marxism has little space for alliances either with the commons tendency or the animist tendencies of the left of the catastrophic parties. They represent precisely the anathema of the future they strive for.

Similarly, one can craft a catastrophic alliance – or rather, an alliance for the regeneration after catastrophe. One can think of adherents of the commons tendency that welcomes animist ideas – and of animists that would favor a commons-based economy. This is perhaps close to the position of Federici herself, of the Invisible Committee, of Haraway, and of movements like Indio é Nós, in Brazil, intending to promote a neo-indigenous way of living, including Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.[36] Commons animists strive to forge alliances between alternative epistemic practices and collective forms of life in a way to minimize the impact of both the Modern age of danger and of capital. They can be grounded on the possible connections between nihilism and capital – and they seem to be many – to claim that both are catastrophic events which ought to be opposed and replaced together. The model could be animist communities like the indigenous groups of the lower Amazon where the social organization resembles in many aspects that of the commons. The commons animists fight both nihilism and capital – including the belief that capital will be eventually redemptive of its own ills. Commons animism could look like the ready-made (cosmopolitical) adversary of inhumanist Marxism even though both stand on the macropolitical left. Both positions make clear that it is easier to make coalitions along the attitude lines (anastrophic, catastrophic) than otherwise.

| N-AP | N-CP | |

| C-AP | Inhumanist Marxism | Post-nihilist Marxism |

| C-CP | ? | Commons animism |

To conclude, I’ll quickly sketch an alternative left coalition that crosses these lines and that I have begun to elaborate elsewhere.[37] The basic idea is to attempt to bring together a tendency of C-AP, Marxism, with some tenets of N-CP. Post-nihilist Marxism rejects the future proposed by the age of danger and, at the same time, holds the idea that the proletarian spells the future of capital. The idea is grounded on an expanded notion of production; a production that is, like that of the schizo of Deleuze and Guattari, not bound by registration or distribution. Production is at odds with the convergence required in intelligence in the enterprise of the persecution of the functioning of things. Thinking itself is productive and, as such, it is indifferent to registration and distribution – it is not geared towards representation and it doesn’t take place in concept engineering. Thinking is not concept manipulation as much as working is not capital expansion. Production by itself is disruptive, divergent, and as a form of production, thinking in dissonance and divergence – it is unified by the efforts to silence dissidence by the will to truth that drives nihilism. The forces of production that are forged by capital will eventually dismantle not only social relations but also the cosmopolitical structure of nihilism. Post-nihilist Marxism is an attempt to play the anastrophe that Marx diagnosed in capital against the catastrophe of the age of danger. If it is successful, it can be a cosmopolitical coalition on the left that combines two different attitudes to two cosmopolitical events. It also shows that alliances can be crafted and that they require going beyond the most straightforward connections between cosmopolitical commitments.

[1] Ludueña, Fabián. Arcana Imperii: Tratado metafísico-político, Buenos Aires: Miño & Dávila, 2016, p. 26;

[2] See “Garrett Hardin’s Letter to International Academy for Preventive Medicine”, 2001, https://www.garretthardinsociety.org/articles/let_iapm_2001.html, accessed in October 2020.

[3] Nietzsche, Friedrich, On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense, Scotts Valley: Createspace, 2012.

[4] Heidegger, Martin. “The Word of Nietzsche: ‘God Is Dead,’”in The Question Concerning Technology &Other Essays, trans. William Lovitt. New York, NY: Harper Perennia, 1977.

[5] Heidegger, Martin, History of Beyng, trans. William McNeill & Jeffrey Powell, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

[6] Heidegger, Martin, “The Bremen lectures”, in: Bremen and Freiburg Lectures. Trans. Andrew Mitchell; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2012.

[7] Heidegger, Martin, “The Bremen lectures”, in: Bremen and Freiburg Lectures. Trans. Andrew Mitchell; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2012.

[8] Stengers, Isabelle, Cosmopolitics I. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

[9] Deleuze, Gilles,& Guattari, Felix, Anti-Oedipus, Capitalism and Schizophrenia, vol. 1, trans. R. Hurley, M. Seen, H. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972.

[10] Land, Nick, Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings – 1987-2007, Ed. Robin Mackay and Ray Brassier, London: Urbanomic, Sequence Press, 2011,p. 338.

[11] Marx, Karl, Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1959

[12] About the convergence and the implications to coloniality see Federici, Silvia, Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons, Oakland: PM Press, 2019; Grossfoguel, Ramón, Colonial Subjects, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003; and Quijano, Anibal, Ensayos en torno a la colonialidad del poder, Buenos Aires: Signo, 2019.

[13] Federici, Silvia, Caliban and the Witch, New York: Autonomedia, 2004.

[14] Stengers pictures the cosmopolitical as a figure of pharmakon (Cosmopolitics I. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.)

[15] Nietzsche, Friedrich, The Gay Science, trans Walter Kaufmann, New York: Vintage, 1974, §125.

[16] Heidegger, Martin. “The Word of Nietzsche: ‘God Is Dead,’”in The Question Concerning Technology &Other Essays, trans. William Lovitt. New York, NY: Harper Perennia, 1977.

[17] Antonio Negri explicitly claims that immanence means that there is no outside. See Negri, Toni, “Politiche dell’immanenza, politiche della trascendenza”. In: F. del Lucchese (org.), Storia politica della moltitudine: Spinoza e la modernità, Bologna: DeriveApprodi, 2009.

[18] See, for instance, Negarestani, Reza, Intelligence and Spirit, Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2018.

[19] More on how the artificiality of Geist in inhumanism connects with the transformation of the world into an (artificial) device in the nihilist process in Bensusan, Hilan, “Geist and Ge-Stell: Beyond the cyber-nihlist convergence of intelligence”, Cosmos and History, 16, 2, 2020, pp. 94-117.

[20] Heidegger, Martin, History of Beyng, trans. William McNeill & Jeffrey Powell, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, §115.

[21] Heidegger, Martin, Introduction to Philosophy, trans. Phillip Braunstein, New York: Palgrave, 2011

[22] This criticism is formulated and investigated on Valentim, Marco Antonio, Extramundanidade e Sobrenatureza, Florianopolis: Cultura e Barbárie, 2018.

[23] See, for instance, Descola, Philippe, Beyond Nature and Culture, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

[24] See Latour, Bruno, Facing Gaia, New York: Polity, 2017; Haraway, Donna, Staying with the trouble, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016; Stengers, Isabelle, Cosmopolitics I, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003

[25] See Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo, Cannibal metaphysics, trans. Peter Skafish, Minneapolis: University Minnesota Press, 2014.

[26] See Povinelli, Geontologies, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

[27] With respect to Marx, see the Communist Manifesto (http://activistmanifesto.org/assets/original-communist-manifesto.pdf, accessed in October 2020), the articles on the British rule in India (see Marx, Karl, “The British rule in India”, New-York Daily Tribune, June 25, 1853), and chapter 32 of Capital, vol. 1. (London: Penguin, 1976).[28] Marx, Capital, vol. 1, London: Penguin, 1976, p. 564.

[29] Marx, Karl, “The British rule in India”, New-York Daily Tribune, June 25, 1853

[30] Deleuze, Gilles,& Guattari, Felix, Anti-Oedipus, Capitalism and Schizophrenia, vol. 1, trans. R. Hurley, M. Seen, H. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972.

[31] See “Machinic desire”, in: Land, Nick, Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings – 1987-2007, Ed. Robin Mackay and Ray Brassier, London: Urbanomic, Sequence Press, 2011,

[32] Moldbug, Mencius, “A gentle introduction to unqualified reservations”, http://docshare02.docshare.tips/files/25499/254992199.pdf, acessed in October 2020.

[33] Federici, Silvia, Caliban and the Witch, New York: Autonomedia, 2004.

[34] Ibid..

[35] Anastrophe was an issue that concerned the CCRU in Warwick and that heritage probably followed the Warwick diaspora after the research unit closed and informed the left-leaning trajectories in this diaspora.

[36] See The Invisible Committee, Now, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017. Elements of commons animism could be found in the traces of the 2014 conference The Thousand Names of Gaia, held in Rio de Janeiro.

[37] See Bensusan, Hilan, “Geist and Ge-Stell: Beyond the cyber-nihlist convergence of intelligence”, Cosmos and History, 16, 2, 2020, pp. 94-117.