“Oil is the undercurrent of all narrations, not only the political but also that of the ethics of life on earth. This undercurrent material, petroleum narrates the dynamics of planetary events from macroscopic scales such as hot and cold wars, migrations, religious and political uprisings, to micro or even nanoscopic scales such as the chemical transformations of substances that are made of carbon.”(1)

—Reza Negarestani

Grounded, Daniel Hölzl’s debut solo exhibition at Berlin’s DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, is permeated with carbon and wax, crucial substances in the structure and operations of human technologies such as aviation: 100 percent recycled carbon fiber, a felt-like textile made out of the offcuts accumulating at composite manufacturing companies, and milky, impure paraffin wax, sourced from recycled candles, derived also from petroleum. Carbon, the element that is fundamental for organic life on earth, is what both substances have in common as they transit through their transformative life cycles. This loop continues internally as Hölzl recycles materials from previous site-specific installations. However, the specter haunting the exhibition is in fact petroleum, not only as the source for airplane fuel but also as a general energy resource which, since its discovery, has fueled geopolitical conflicts and contributed to the deterioration of natural habitats. These materials find their way into Hölzl’s works through a series of wax paintings on carbon fiber, ready-made components, and sculptural parts, all of which are in some way extracted from the aviation industry and connected to notions of being grounded.

Grounded is not just the presentation of a series of works by an artist, but the creation of a unified yet complex world made up of substances, materials, and forms that reflect the conceptual, historical, and social concerns guiding the artist’s research and practice. By reconstituting the entire gallery as an “aviatorial space,” Hölzl establishes a setting for probing reflections on the connections between nature, science, and industrialization through the overlapping history of aviation technologies and the recently renewed European legacy of war and conflict, highlighting the integral role of petroleum.

The first object that greets visitors establishes the relationship between materials and their use by the artist. Suspended diagonally, the wingless plane hangs head down towards the gallery’s main entrance, almost grounded. The object is an airplane fuselage belonging to the Austrian company Diamond Aircraft’s model DA42, a prototype that, though it never flew, was nevertheless the first ever monocoque fuselage exclusively made of carbon and glass fiber composites. These substances, consisting of fibers embedded in a resin, form a lightweight but hard and nearly indestructible safety shell.

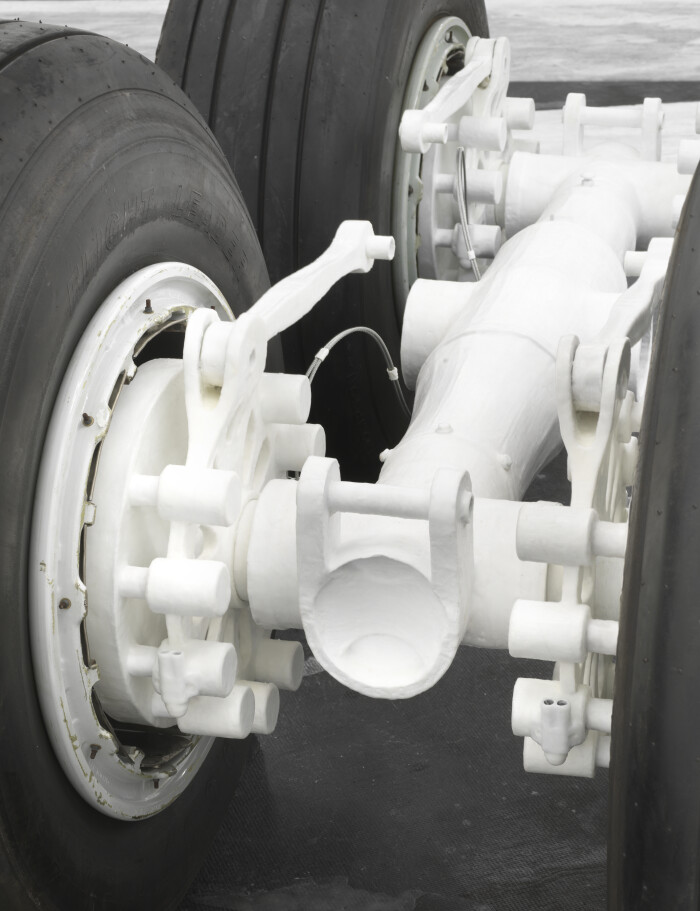

Downstairs, the entire floor of the gallery’s viewing rooms is covered with carbon fiber felt. The floor is then imprinted with a scale replica of the letter X, which stretches from one room to another. The X, a universal sign observed by pilots that indicates an inoperative runway, is taken from one of the two runways belonging to Berlin’s old Tempelhof Airport. Resting on the floor of the large viewing room is a set of airplane wheels attached to their landing gear, normally equipped with four wheels but here missing one. The wheels and their rims belong to an Airbus A300, the first plane produced by the joint European company Airbus in whose construction carbon fiber was extensively used. Nearby, a replica of the missing wheel, cast in recycled wax, slowly melts and is absorbed by the special floor beneath.

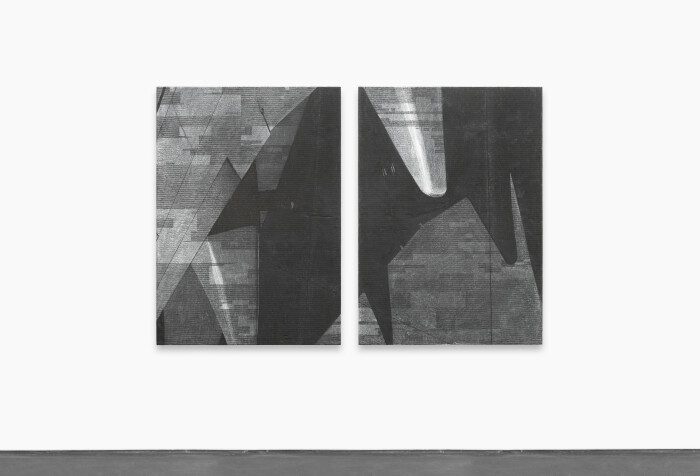

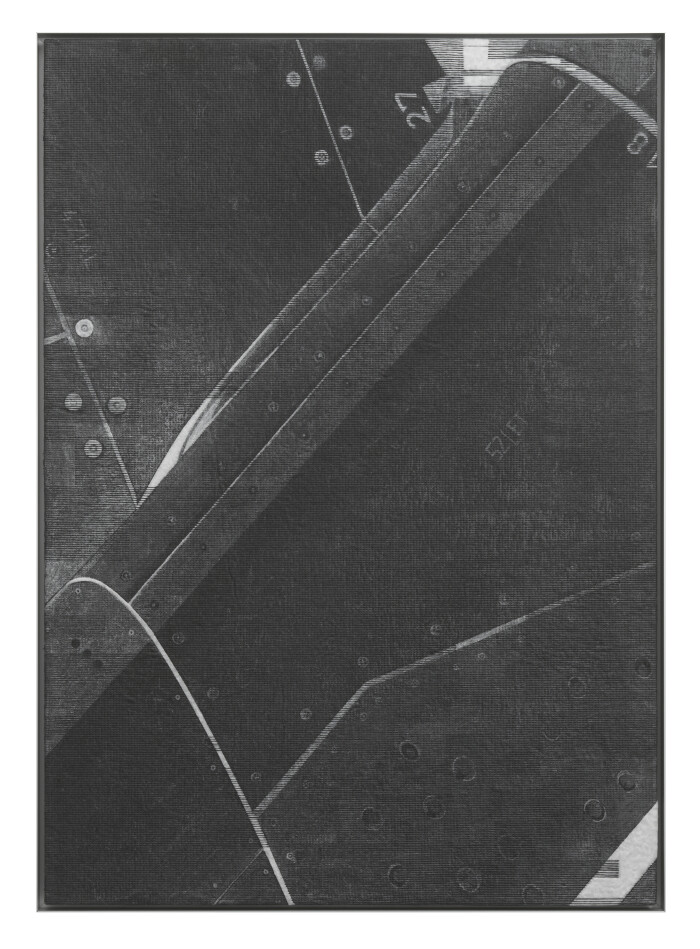

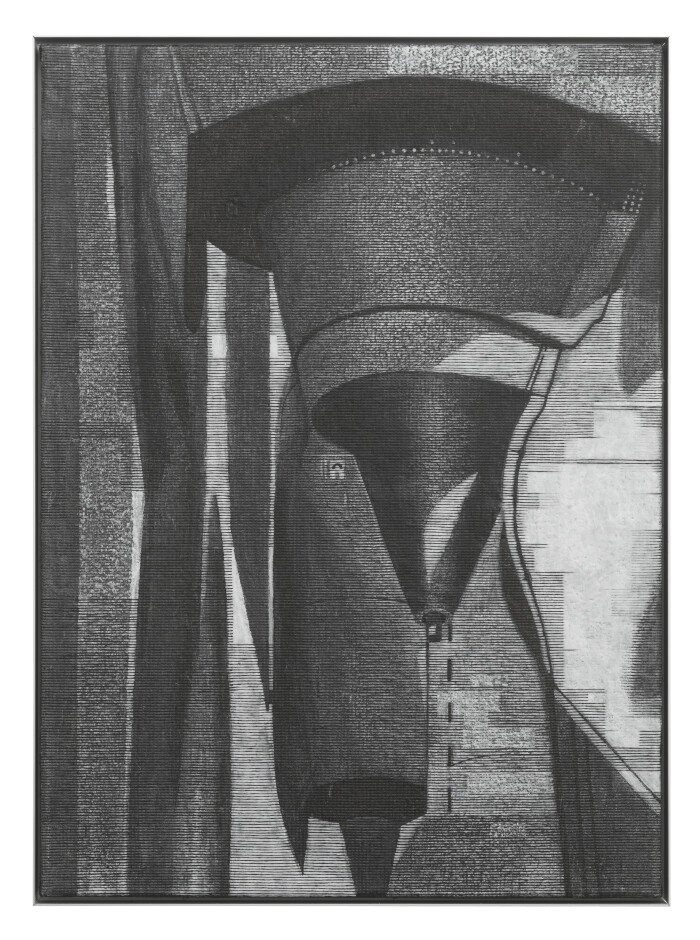

In Hölzl’s paintings, the canvases are made of carbon fiber and wax functions as paint. It is absorbed by the support like the melting wheel, similar to how resin saturates carbon fiber to form the shell of the fuselage. Smaller works are hanged in a row reminiscent of airplane windows; the canvases, cut from the same fabric that covers the floor, leave the underlying concrete exposed. Most paintings are framed in aluminum, another key material in airplane construction.

Following airships, during the first revolution of human aviation, wood, fabric, twine, and steel were used to make the earliest powered heavier-than-air planes. During the second revolution, most of these materials were replaced by aluminum. The third revolution in aviation technology incorporated carbon fiber, and today composite materials make up 80 percent of plane structures. The plot twist here is that this saves fuel in flight, but complicates the recycling of the airplane.

The abstract yet recognizable motifs depicted in Hölzl’s paintings are based on photographs of airplanes that the artist reconfigured before painting. He began the series after his relocation to Berlin, where he lived near to the historic Tempelhof airport. Further biographical references help explain his fascination with aviation and its wider context. Photography was a household activity for Hölzl’s family, and both his grandfathers were trained in the world of aviation during the Second World War— between them they were involved in radiocommunication, manufacturing and piloting aircrafts.

Ever since his childhood, Hölzl has been drawn to the world of aviation, seeking both to gain insight into its role in history and to better understand his family.

Rendered in negative as well as positive impressions, the paintings include closeups of engines, curved fuselages, and diagonal wings, as well as geometrical shapes taken from tarmac markings. In these paintings, organic substances and simple geometries unify as wax and carbon fiber interact. Research and experimentation with the physical properties of his chosen materials have led Hölzl to develop a unique method for making images: he first saturates the textured dark gray carbon fiber canvas with wax then later melts away some parts to create the positive and negative spaces captured in his analog photographs.

Art history teaches us that the most memorable paintings are those in which the artists have successfully synthesized their final impression of the motif by matching the optical experience of the paint on canvas to the perceptual affordances of the human eye.

Hölzl’s method for arriving at a similar result begins with paying attention to the painting’s support material. His slow and careful application of wax to the canvas followed by the tracing of the warp and weft of the carbon fiber when rendering his images allows him to create solid and smooth areas of white on top of the canvas before melting the wax into the horizontal ridges of the fabric, bonding them casually. The wax in the solid and saturated parts appears to be bursting from the fabric, while the low-saturated parts rendered by deduction and melting seem to be seeping out from behind the canvas. The resulting lines in the image have an eerie similarity to low-resolution lines in analog video images from the early television era, sharing an affinity with glitch aesthetics. We may even go so far as to say that the machinic precision of Hölzl’s paintings camouflages the artist and removes his perception that normally mediates like a filter between a painting and its viewer. That makes these works evidence of a quasi-magical process in which painting itself appears to make sense of the digital and the immaterial solely through the physical characteristics of carbon-based substances and following geometric logic and analog methods. The anachronistic genealogy of these works remains transparent without needing any literal reference.

The exhibition’s palette is limited to grayscale even beyond these paintings. Exceptional hues emanate from the impurities of both the recycled wax and the carbon fiber. This chromatic minimalism renders the optical experience similar to that of a black-and-white film. The only other colors in the exhibition come from the bright yellow and black rubber chocks that ground the airplane wheels on the floor of the main gallery, or from the visitors.

History has always been the future of the past in present tense. It has been reported that NASA is planning to phase out the International Space Station by crashing it into the Pacific Ocean. A lot has happened since the Swiss architect Le Corbusier saw the first airplane flying over Paris in 1909. In the festive atmosphere surrounding the technological innovations of his time, he reportedly reacted to the sighting of the plane circling the Eiffel tower by saying it “was miraculous, it was mad.”(2) For modernist artists in the interwar years—think of Sonja and Robert Delaunay—the airplane was the promise of futuristic modernity. And the modernists weren’t alone: “In America, an air-minded nation looked upon the Wright brothers as quasi-messianic inventors of a ‘wondrous, even miraculous machine.’”(3) Many viewed the invention of airplanes as the fulfillment of a prophecy, bound up with secular virtues such as enhanced mobility, prosperity, cultural elevation, global travel, social harmony, and peace.

Across the decades and into a twenty-first century marked by the impacts of climate change, war, and the recent geopolitical realignments within Europe, aviation has continually undergone major transformations. While its increasing role in warfare has advanced the military wing of the aviation industry, the civilian air travel business has been placed under an increasing level of security, marking air travel a sensitive site ripe for scrutiny by the state. This heightened tension was recently exacerbated by the pandemic as well as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its impact on fuel prices, either limiting or even grounding aircrafts.

The aviation industry’s worldwide operations are said to produce only 2–3 percent of human-generated CO2, comparable to the iron and steel industry (5 percent), cement production (4 percent) and shipping sector (3 percent(4). However, even disregarding the environmental impact of aviation, a global industry governed by the logic of the free market has considerably lost its emancipatory potential envisioned in the early days of aviation. By aestheticizing the scientific and industrial history of aviation and its significant practical applications in the world, Hölzl’s exhibition initiates a timely conversation about its fraught subject matter.

European countries began to deploy motor airplanes not long after their invention, equipping them with firepower in the service of their many colonial wars. Lest we forget, the event that inaugurated air warfare took place in November 1911, when an Italian airplane bombed forces loyal to the Ottoman Empire in Libya. “Today I have decided to try to throw bombs from the airplane. It is the first time that we will try this and if I succeed, I will be really pleased to be the first person to do it,”(5) wrote Giulio Gavotti, the airplane’s pilot. Later on, World War II became the stage for the fiercest air battles to date, followed by America’s carpet bombing of Vietnam and Cambodia in the 1960s and 70s.

More recently, the same country’s internationally sponsored „War on Terror,” which continued for twenty years, from the invasion of Afghanistan by the U.S. and its allies in 2001 to the country’s sudden abandonment by the same occupying forces in 2021, is a reminder of the emergence of unmanned and guided drones as the latest aviation technology.

Grounded, while possessing abstract qualities associated with formalism, points to aviation’s dangers and limitations, rendering its existing characteristics like petroleum dependency and utilization in permanent wars around the world as already outmoded, grotesque, and nostalgic.

We must ask ourselves: What kinds of materials, forms, and sources of energy can significantly enhance our aviatorial abilities while having the least impact on the environment? Can we essentially transition from capitalism to a post-oil economy? What roles can innovation and automation play in these transitions? And what will be grounded in the future?

NOTES

1- Negarestani, Reza. Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials. Melbourne: re.press, 2008, p.19

2- Modernity’s Object: The Airplane, Masculinity, and Empire Robert Hemmings Criticism Vol. 57, No. 2, Critical Air Studies: A Special Issue Edited by Christopher Schaberg (Spring 2015), pp. 283-308 page 283, published By: Wayne State University Press

3- Violence, War, Revolution: Marinetti’s Concept of a Futurist Cleanser for the World Günter Berghaus Annali d’Italianistica Vol. 27, A Century of Futurism: 1909–2009 (2009), pp. 23-71, page 29, published By: Annali d’italianistica

4- See: https://aviationbenefits.org/environmental-efficiency/aviations-impact-on-the-environment/

5- For more on the invention of ari warsee: “Libya 1911: How an Italian pilot began the air war era”, Alan Johnston, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13294524

DOCUMENTATION