In the epistemic context of terraforming, geoengineering, and geophilosophy, this essay navigates the literary ecosystem through certain poetic devices, derives a conceptual trajectory, and applies it to its own architectonical posture. In it, we attempt to formulate an understanding of new experimental domains in the terrains of literary ecologies, specifically the surface of the desert, with examples from Frank Herbert’s Dune and Edmond Jabès’ The Book of Questions. This comparative approach will take into account modes of conceiving the machinery that articulates the formlessness of different textural threads and intermeshing surfaces, and the kinetic excess of the navigation of the desert in relation to the concept of theoretical installation, introduced by François Laruelle in his book Photo-fiction, a Non-Standard Aesthetics, reviewing the conjunctions of thought and writing that interact to generate an experimental device that juxtaposes two matrices with “dual input” (p. 19) in order to integrate fiction and theory in a novel model of creation, writing and thought.

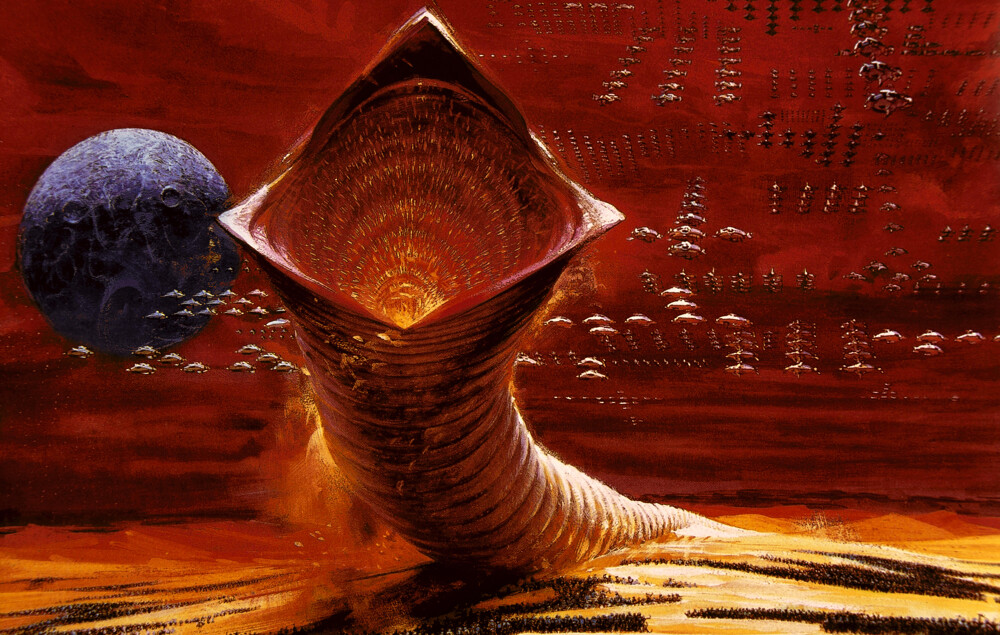

While Dune is a novel about sandworms, like dragons, guarding their spice underneath the planet’s ocean of sand, The Book of Questions folds back into itself the threshold of writing in the desert-like totality of fragments following the movement of initial rupture from the broken word. Both blend together into cosmic transformations of the textual outside; translating altered psychic states and the paradigmatic appendages of ecological phantasmagorias of the desert that represent a boundless organismal labyrinth in writing.

In order to understand the internal relations of such a stratagem we need to frame how this operation performs in parallel in both ecosystems. We will follow Dan Mellamphy’s reading in “Ec[h]ology of the Désêtre”, taking into account the concept of fragmentality as a literary device that offers us a principle of design intermingled with the concept of the metaphor to explore, through the concept of the desert, what goes beyond naming in speech and can only attune itself to the unspeakable, to silence, and also to the navigation of temporality, the limits of personal identity and the mind’s relationship to the body.

The infrastructure of this essay includes different paths drawing distributed networks of a cunning poetic intelligence, built on a constructive principle which penetrates the fissures in the surface of the earth. The image of the drone is composed as a technical device that concocts a stereoscopic “Travelling Eye of God,” as Benjamin Noys defines it. Only from this aerial perspective can the whole surface portray the multi-layered facades involved.

According to Andrea Brady in her essay “Drone Poetics”, the landscape of the Afghan valley dictates a terra nullius, placing the drone in a ‘God’s-eye view’ that looks at the valley as “an untreated, unhealed body; irregular and odd: associated with snakes, dirt, ruin and isolation. The landscape becomes a Kleinian array of primitive experiences of death-dealing and libidinal desire” (p. 122). The drone “tricks us [into] believing that we are omniscient beings, diviners, foreseers, and prophets… it presumes that a top-down perspective allows us to know everything: foreign cultures, personal interactions, internal spaces, the whole of the past, the present and the future“ (p. 131).

Like a drone, in Dune the hunter-seeker is a little floating knife that is operated remotely to fly and to kill, allowing for an interaction between organisms and environments. According to Dan Mellamphy (p. 394), this ecology entails the dynamic project of a dromology (Virilio, p. 55) between “elements in relations of speed and slowness” specifying the level of “zero intensity” or “ground zero of all production” guiding the book through an “ecological literacy.” In this context “zero” can be considered in three senses: the metaphysical, the cybernetic, and the alchemical. Mellamphy (referencing Malfatti) argues that the metaphysical value of zero, which takes into account the Pythagorean mathesis universalis, places the tetract in the void of what he classifies as the “very engine of ontogenesis” and establishes the cybernetic feedback loop as a “circuit always in motion” (p. 393).

It is on the third alchemical sense that we will focus in order to understand the proper milieu of the operation experiencing this dromology and the spaces it is immersed in. A figure from the “Bene Gesserit” in Dune individuates herself through the ingestion of a drug, the Water of Life, with which she dissolves within herself the alchemical blackness?the nigredo?that allows her to articulate her own language, as “it is the [non]language of egos [with]drawn back the dust, mixed with the mud, sunk into the sand,” the “unspeakable wormtongue, the logos alogos of earthworms” (p. 398). We observe how this language is itself intrinsic to the earthy conformation of its gaining the poetic register. It does so within dimensions of potential space that wonder at such transformations after excavating all the potential objects in the immense vessel in the unknown depths of the desert.

In parallel, Mellamphy defines the thought of the Nietzschean Übermensch as one that breaks apart and ruptures the system and makes it a continual interruption. In this sense, the thought of the Übermensch creates through this fragmentation when it overtakes the assemblage as a “multiplicity of figures” that it illustrates in the image of the “speck of dust, squashed little spider, crushed earthworm, gob of spit trampled under foot by the passage of time” or is being “eclipsed… at the point… which reveals the fragmentation of self-realization” (p. 86). Such solitary thought twists the axes of space and time, allowing words to float around, ensuring the redundant encounter in the fragments of extreme pressure of air littering elsewhere from the footsteps on the surface of the planet.

Jean Baudrillard, in his book America, defines the fossilization of the gaze that takes into account the geological and metaphysical surface of the desert through pure speed?an echo of the void in the desertification of the social, the “desert speed” (p. 5) as an “ecstatic form of disappearance” (idem), gathering clandestine segments of a vacuum of history, grasping the fields without remainders of the inner conversion to a hallucinatory delusion in the universe on the outside.

But for Jabès it is the hand of the scribe that articulates the flatness of the place in the text, beyond any concern with geography. According to Mary Ann Caws, Jabès manifests a creative tension that speaks about exile in the exchangeability between center and margin, “the silence of the desert renewed by the shifting of its sands” (p. 13). The drone that presents as the “travelling eye of God” is revealed in Jabès as the projected target of the Promised Land in the tradition of the Shekhinah, as the “absence of any place of true abode beyond itself,” the inextricable condition of nomadism of the tongue.

Maurice Blanchot tells us of the catastrophic status of writing in The Book of Questions, where inscriptions persist in the perpetual discontinuation of distance and impossibility, presenting a Desert Theology of absence which acts according to the “place-name,” finding a language through asceticism: “the prayer seeks a language for those evaporations, disappearances, mirages, and obscurations which are inner as much as outer” (p. 5). Complementing this, Baudrillard argues that the desert finds its place in astral hybridity, defining it as a “luminous, fossilized network of an inhuman intelligence, of a radical indifference?the indifference not merely of the sky, but of the geological undulations, where the metaphysical passions of the space and time alone crystallize” (p. 6).

Returning to Mary Ann Caws, the silence of the desert in Edmond Jabès is considered the precise starting point in bareness, but is also in the gaps that resonate as a living opacity in the surface of writing, as “you don’t see the image; you see no colors, only transparency, as if it were mad of a million colors, a million aspects for seeing, angling, interpreting the shifting shades” (p. 12).

Following this, Francois Laruelle comments, in his book The Concept of Non-Photography, on the concepts of force of creation and “force of irregularity”, which conjoins a “wall of writing, not only a surface or a becoming of thought, but a self-similar grain of writing” (p. 127). With this notion, he proposes the “absolute interruption” of language in the figure of the One-Book bearing what he coins as an incendiary linguistics a priori, “Il y a une interruption absolue, irreversible, qui precede le lapsus du langage, c’est-a-dire la glissade ou le flux du Logos…” (p. 128). Poetic perception and critical perception are merged together to show us the dark opacity of the phrases that lead to silence rather than to exegetic commentary.

In Jabès, the desert finds its hallucinatory place in the “atmosphere of the pulverized letter” of the characters that have removed themselves from the writing: Yael, Elya, Aley, they either get killed or lose their corporal and imaginary existence; their incendiary disappearance encircles each letter. Jabès encompasses the foundation of the excessive vanguardism of the book’s secret, when writing operates according to the outer simulation of emotion intrinsic to the phenomenal blackness of the letter and the word, the impossibility to imagine what ties together experience and representation in language. This is a perspective that effectuates an explosion leading to the “informe” of a genetic grain leaping backwards in the ashes as it rises from the scene of the fragmental tablet of the book itself, its deep-set ash intervening with the catastrophic term without the metaphor, “il n’y a pas de metaphore de l’innommable” (Laruelle, p. 129).

According to Anne-Francoise Schmid in her text “Critique de la metaphore sufficent”, the relation between philosophy and rhetoric surmounts its typical limitations to reach for catachresis in the search for clarity and transparence, opposing them to obscurity and opacity, taking into account the continuity and discontinuity of its ornamental status, the scalpel that dismembers the body of representation, finding the ground in the fine cloth stretching across the formless network of the continuum. As Schmid specifies, “on peut donc pratiquer le renversement quasi-topologique de contraires, mais, renvoye a l’infini, et non pas donne,” (p. 245) when referring to the analogical immanence that performs the sequential series in the semblance of a circular objectivity in language, that communicates to a quasi-exterior alter-dimension which is the writing of the commentary, as Jabès does, with the emphasis on the written word, on the letter in itself?a writing manifested as the movement of the enigmatic and mysterious origin that registers the differential as a rupturing point.

This is also the horizon of the desert that Eugene Thacker helps us understand when “language produces a lost synthesis via a phoricity of affirmation” (p. 88). This term works catastrophically as an epekinaphore, allowing for the ossification of metaphors used in philosophy whose conceptual terrain is mysticism to pass beyond the limits of silence itself, and “in-the-last-instance, to allow the futurity that comes in the fiction without the logos, when the desert works as both discourse and its negation… this inaugural formula in effect signifies the limitrophic exceeding of all terrain” (p. 90).

Schmid further argues that Laruelle assumes the suspension of the sufficiency of the metaphor when he affirms the radical identity of the name and the word, and it is exactly at this point that we want to conjugate what he simultaneously calls linguistique catastrophique when glossing on Jabès.

Returning to Dan Mellamphy, we consider his emphasis on the “mythogenesis” of artifactual logos taken back to nature in the necessity for understanding the homologous sources of the environment and the physiological when he takes into account in Dune the shifting terrains of the ecology of the book, making explicit the auto-consumptive principle of Shai-Hulud and the drug that has to be ingested in order to experience the placeless place, the out of time “impersonal pit” that presents the non-language of the ecologist, something that resembles a scream as “[t]he death-scream of a desert hare shocked its way through him” (Herbert, p. 279).

In Dune, Frank Herbert crafts a universe where the colossal worms quake in the tremulous surface of deserts and vast dunes of the planet of Arrakis, producing the drug melange. They are attracted to the vibrations of the surface reproducing the machinery of convergent waves of the rhythmic spawning above, in a process simulating their gluttonous core.

This is the alchemical baseline of nigredo dissipated across distributions of voids. Like the dragon devouring its own tail, the belly of the dragon is the desert of words and worlds.

They break through the labyrinthine thread interweaving organism and environment in a defiled composition of montage artificiality, where the spectator travels across the terra nullius in the assembly of the Book.

The convergent multitude stretching the bite-wound mouths in the surface of the dune triggers the infesting holes of a circuit operating remotely from the feculent nether ocean of a Galactic Stomach Ache. The voiding processes incubate the logic of the predestination of cybernetic top-down rule wandering routes in the aerated waters of Tartar.

Such a BELLY is the fossilized prototype of a carbonated scream suffusing all cosmic degrees. “Into the burning lake their baleful streams” (Milton), this lake turns its serpentine indigestions into tartareous deserts flowing towards dark paths of zero distorting time and pulverizing the word, the letter, and the tongue.

The BELLY overthrows the scream and there is no further erasure in language. The graven silence of beyond in the metaphor is a woven rope of written gaps of a story-fabric from multiple foci in the multiplicity of figures of speck dust. Wounds sewing the traces of spider’s nets in the act that conforms the hand, the eye, the needle joining the fragments through stitching and piercing the wire-mesh flesh.

According to German Sierra, “the desert is full of drones” (p. 28). In this essay, we have focused on certain degrees of inhuman, alien and catastrophic ecologies (of desert in/of language), and their interaction in chiasmi of biomorphic environments between the labyrinths of the chthonic tongue and sand-like silence in eternities of dust. Drones and deserts are experiments that reveal themselves through superimposition, modulating the gaps of their unverifiable tendency to refuse their telluric auditions. They reinvest on the vociferous vector of language in order to suture their pivotal rumbling that returns as a feedback loop. The desert was the last scream. And then the worm swallowed silence.

From this point of view, such postulates would be oriented in the service of the text functioning as a flux instantiating a previous model of action in the sense of a vision going backwards, inhabiting such an effect as a theoretical installation. At this point, the transfusion of meaning from different perspectives displays the organization of a transversal combinatorial choreography operating according to textual affirmative repetition, translating the problematic of the differential in the textual machines that undermines the externality of the reference.

These differences are primordial generalized categories presupposing dualities in the textual fiction of the repetition, and will simulate reference at the zero degree. In this way, they will resist its signification in a double inscription where the superior term of the signification excludes the external significant, disseminating the voice infinitely in the labyrinth of phone. These strategies display the chasm of alogos, allowing for an interaction with the chthonic surface. The phone oscillates as the scream of the pragmatic continuum.

Screaming would perform the unity-of-name: the effect of the transcendence of the Book {the space of writing-degree-zero} relating to the One-Creator, destroying its ontological position to present his Creation-Book as the precipitation of the creature-of-writing individualizing the letter-sign beyond intelligibility. It would present the formlessness of the vision as an absolute interruption, preceding the flux of logos creating the term in its unity, eliminating any metaphor of the unnamable for the sake of an “a priori incendiary linguistics” (Laruelle, p. 129), conceiving writing as a radically integrative object about to explode the gap of the fragments.

This explosion is also the conversion of the unlimited-becoming-photographic stance devoid of the metaphor of all surfaces and topologies, departing from pathologies of rain and thunder, through the tele-portation of a generalized metaphor as the passion for a quasi-space of the universal wall leaving the Testament in the genetic grain of its imaginary number:

a Testament twice,

a spell for the oracular suspense of vertigo

unheard night of ocean-fishes

in a bubbling language of black sentences

employing real-identity-in-the-last-silence

without noise mixtures.

_____

REFERENCES

Baudrillard, Jean. America. Verso, 1988.

Blanchot, Maurice. “Edmond Jabès’ Book of Questions.“ European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1972, pp. 34-37.

Brady, Andrea. “Drone poetics.” New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics, Vol. 89-90, 2017, pp. 116-136.

Caws, Mary Ann. “Edmond Jabès: Sill and Sand.” L’Esprit Créateur, Vol. 32.

Herbert, Frank. Children of Dune. Berkley Publishing Corp, 1976.

Herbert, Frank. Dune. 40th Anniversary Ed. Ace Books, 2005.

Jabès, Edmond. The Book of Questions. Wesleyan University Press, 1991.

Laruelle, François. “Le point sur l’un.” In: Stamelman, Richard Howard, and Mary Ann Caws (eds.), Ecrire le livre autour d’Edmond Jabès. Champ Vallon, 1989. pp. 121-132.

Laruelle, François. Photo-Fiction, a Non-Standard Aesthetics. Univocal, 2012.

Laruelle, François. The Concept of Non-Photography. Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2011.

Mellamphy, Dan. “Ec[h]ology of the Désêtre.” Collapse, 2017, pp. 387-409.

Noys, Benjamin. “Drone metaphysics”, Culture Machine, Vol. 16, 2015. http://svr91.edns1.com/~culturem/index.php/cm/article/view/595/602

Schmid, Anne-Françoise. “Critique du principe de métaphore suffisante.” In: James, Denis. Les dérives de la métaphore. L’Harmattan, 2008. pp. 199-210.

Sierra, German. “Writing Noise: The Maze and The Drone”. Litteraria Pragensia, 2019, pp. 7-31.

Thacker, Eugene. “Notes on the Axiomatic of the Desert.” Angelaki, 2014, pp.85-91.

Virilio, Paul. Pure War. Semiotext(e), 1983.