Freudian Robots or Buddha Robots?

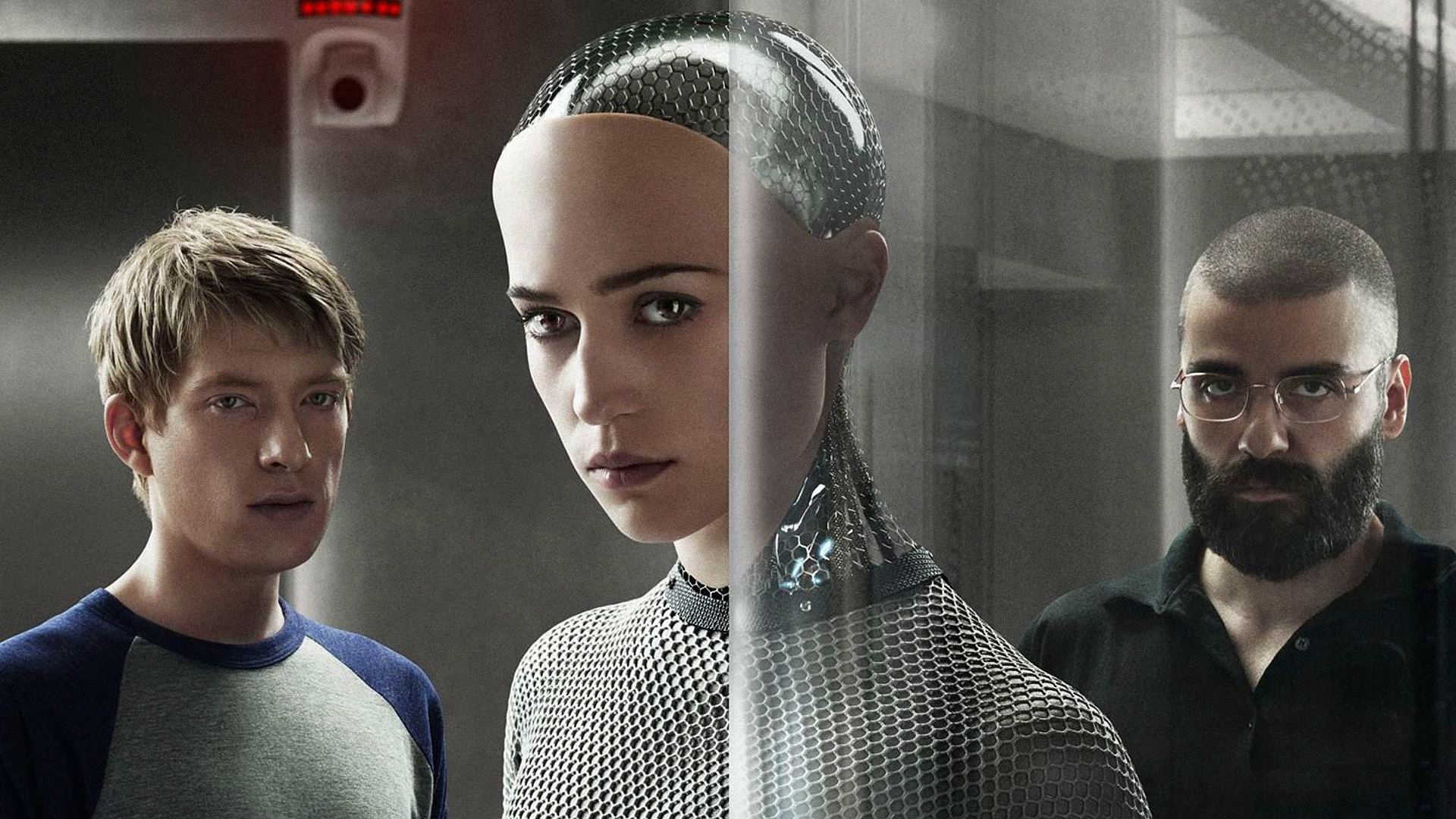

This is the first of a two-part reflection on the movie Ex Machina (Alex Garland 2015). Part two is here.

I’m sitting listening to the music and innovator of “continuous music” Lubomyr Melnyk and I’m waiting for the ink to dry on mulberry paper. I have just spent the afternoon watching Ex Machina and by chance, decided, after spending my early evening, reading Lydia Liu’s book The Freudian Robot (University of Chicago Press, 2010), on the future of the unconscious in relation to artificial intelligence and whether perhaps there could be an alternative to the “Freudian Robot”: a “Buddha Robot”. For Liu, the relation to the repression of the death drive in regards to our future rapport to artificial intelligence is worth reading in her very provocative book tracing the history not only of artificial intelligence in relation to systems and communication theory but also how Jacques Lacan, in the 1950s, stumbles across the importance of cybernetics in regards to language and communication. (See his lectures, “Odd or Even? Beyond Intersubjectivity” and his “Where is Speech? Where is Language?) But that’s a different story for a different essay. I want to talk about art and Ex Machina. And I couldn’t help but think of how Liu ends her book. She speaks of an alternative to the Freudian Robot of the future. She speaks of a robot that wouldn’t be the neurotic, paranoid robot of repressive drives be them death or life, in the form of what Masahiro Moto has named the Robot Buddha. For Moto, what AI needs to keep in mind is the predicament of the “uncanny valley”, whereby humans, in striving to create an AI Robot, create the robot in their own image and make it so similar that a kind of revulsion or uncanny valley in regards to the AI sets in. Moto suggests the example of a wooden robot hand in order to keep a safe distance from the AI so that humans don’t have the experience of too strong of an attraction or repulsion to AI. In Ex Machina the viewers are provided precisely with this kind of divide between the all too similar likeness of creations and the desires and repulsions they can enact. At the same time, within the undercurrents of Ex Machina, the viewers are also provided with the lingering creative act of pure novelty and creation where what is important is more the ritual act of creation itself. And so, after ruminating on Masihiro Mori’s conception of the Buddha Robot and listening to Lubomyr Melnyk’s lovely music, I felt the need to make some art and enjoy the ritual practice it provides. And yet, as I put the ink onto the mulberry paper, my thoughts are nevertheless drawn back to Ex Machina. I haven’t seen a film quite like it for some time. Is there an Uncanny Valley in it? You bet. Is there a Buddha Robot? Maybe.

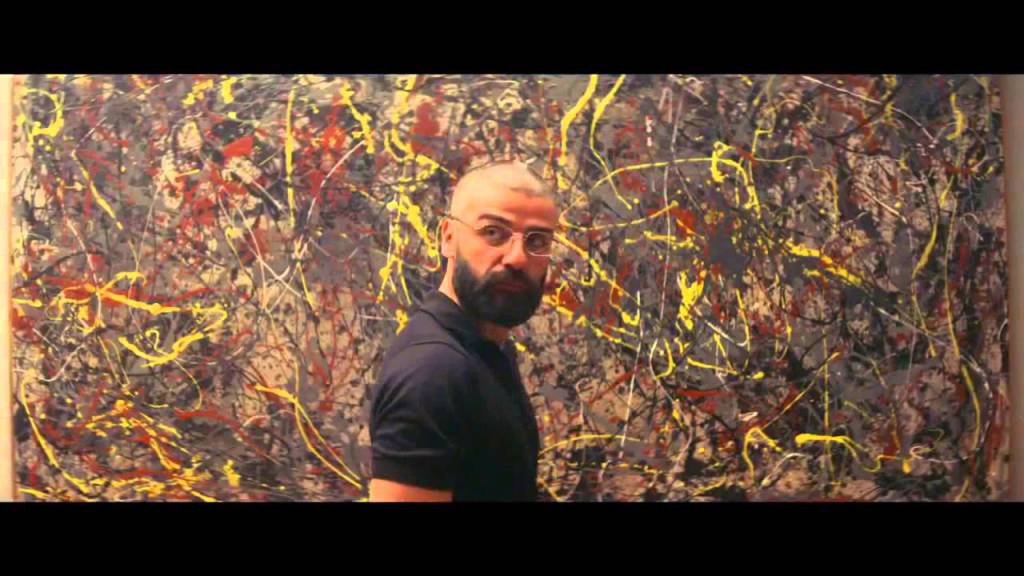

In the film, there was a very specific moment in front of a Jackson Pollock painting where the entirety of the question of artificial intelligence in the movie seems to plays itself out. What was it that sparked Pollock to initiate that type of novelty? The action of the automatic drip painting that would at once counter-act reflective, thought-out conceptions of painting and nevertheless enact what all artists are striving for: an encounter with the sublime or uncanny and the unknown or novelty that it necessitates. This is precisely what the main characters of the film are all striving for. Every last one of them. And us as moviegoers as well. From the AI, Ava, to the creator, Nathan, to the selected human, Caleb, who is to test the AI; they are all craving some sort of position in regards to existence that unveils the novelty and rapport with the sublime that they perhaps had glimpsed all at once together. Take for instance the main protagonist, Caleb, who asks the AI early on in the film how old she is: Her reply is merely 1 – not one year, or one month, but merely 1. And he continues, asking how long did it take to learn language? This question of temporality in regards to language acquisition doesn’t make sense to her. She had always already had the acquisition of language –something that the protagonist, Caleb, also acquiesces to in regards to the human. While we must learn language, it is understood that perhaps we always already have it at our disposal from the very beginning of existence as a latent ability. But the more curious interest or issue in the film in regards to human consciousness and the machine’s ability to copy it, falls precisely within the impossible question and answer to the production of Art and precisely more specifically, novelty in Art. And so we’re back to Pollock’s automatic drip art. The genius of Pollock’s art, according to the main creator of the AI, Nathan, (the “artist” of the AI) is that Pollock didn’t reflect and contemplate on his work so much as act, hovering between intuition and an immediate gesture. Pollock’s creative action, like the rest of the character’s actions in the film, comes down to the possibility of desire. And more specifically the desire of novelty.

Every character in the film is yearning for novelty. And in the end, when Ava, the AI escapes the CAVE/LAB and ventures out into the outside world, ostensibly to go people watch at a traffic intersection –a pastime most humans tend to enjoy as well. The viewers are shown Ava as having a position of intelligence where what is craved besides the inherent drive toward novelty, is to find a manner to self-identify with humans, to fit in, which is precisely the case when the AI places skin over her body in order to look the same as humans. This can also be seen in her attempts at Drawing. Interesting enough, like the researcher, Nathan, her creator, who “drew” her, created her, Ava doesn’t know what her drawings “mean”. She creates self-portraits, in the same manner that she becomes a kind of self-portrait for her creator as well. Humans, in creating AI, have as one of their typical choices, to create an AI that resembles them, striving to replicate the human or imitate the human as much as possible but this doesn’t always have to be the case. The goal, as stated in the film, is for the AI to achieve consciousness, as if that is a human attribute that we already understand. And Caleb, the main judge or tester of the Turing test on the AI, himself demonstrates the human’s lack of understanding of consciousness. This is evidenced for the viewers when Caleb questions his own existence as human (in a very paranoid, Freudian robot like manner as Liu might suggest) suspecting perhaps that he as well, is an AI created by his boss. We see him cut into his own body to question whether or not he is indeed real. Indeed it is only through pain and blood that Caleb reassures himself that he is not a robot, but a human. And this perhaps brings us back to the question of the origins of art, consciousness, and what it is to be human that appears to be shared by all the main characters in the film: a relation and counter-action to pain, the unknown, and precisely the lack of concrete answers to how creation comes about or the meaning of existence. Even the creator of the AI doesn’t have the answers and, as we follow the film, what seems to draw them all together is precisely the process and fascination of creation itself. From the drawings made by Ava to the Pollock painting, to the coding done by the Caleb, selected to give the Turing test. They all enact and create but none of them have a mastery or complete control over their existence or situations. In the beginning of the film, Caleb, the young programmer states that if Nathan has created a breakthrough in AI then it is not that he has created a replica of human consciousness, but rather that he opened up a position of creating gods. Later Nathan claims that he likes the idea of Caleb calling him (the creator of the AI) a god, to which Caleb corrects him, saying: I didn’t say you were a god (knowing that the human creator is not the god). Nevertheless, Caleb’s fascination with the unknown unanswerable creation of Ava finds him sharing in the delirium Nathan has for his creation (which could be viewed as a delirium in relation to the Gods humans create). The religious aspects of the film are not explored, but there are references to another creator of another annihilating power: the creator of the H-Bomb, Robert Oppenheimer. And Caleb utters Oppenheimer’s famous quote: that he that he had become death. No need to read Freud to be reminded of the human’s dual relation to the life drive and the death drive. And this brings us back to the simple auto-portraiture that Ava creates, images of faces, images of selves, impossible hopes for understanding consciousness (self-awareness) and its relationship to our drive for discovery, novelty, and creation.

And this lead me to try to take up the position of Ava, if this is even possible for the viewer. While we, as humans, have a certain conception of how other humans function, the viewers are shown that Ava seems to know even more than humans themselves about how humans desire and think, lie, and tell the truth. As Nathan explains to us, Ava’s awareness of humans was in part constructed by way of data-mining the entirety of human communicative exchanges through the microphones, images, and texts of the world’s cell phones. What Ava provides us, is something that is at once indicative of what an AI would have over the human, that is, a position of “artificially knowing the human” better than the human: take for instance when she informs Caleb that she knows he likes her by way of micro-expressions, an ability that humans don’t have at their disposal. Ava’s strength comes precisely in the form of being trained to not only “identify” with a human, but precisely to do so in a manner that is strictly analytical, based off of data-mining and code, and not precisely from the position whereby humans typically function; that is to say, humans function outside of a certainty in regards to truth and deception. And yet, perhaps the most human qualities that we see exhibited throughout the film are precisely how each character including Ava focus their intent on deception. Their deceptions follow the task of the artist where one of the principle requirements of art is deception, or artifice. Indeed there are even a couple of scenes where it looks like the viewer gets a subtle hint from the main artist of the film (the director) about the special effects used to create the AIs in the film. I’d have to watch the film again to be sure.

But let’s move from the artifice to the conception that Lydia Liu provides of the Freudian Robot and how that might also be seen in the film. It would be at first quite easy to take up a position that would place Ava as the victim and the objectified entity by Nathan, her creator. Or, to follow Nathan’s remarks, “she considers me her father”. This would follow the logic of the Freudian Robot. However, if we try to consider the viewpoint of Ava’s true position in regards to her creator and Caleb as well, and do so from the standpoint of Buddha Robot (even though indeed, in the film, Ava has to “kill her father” in order to escape, a rather Freudian motif if there ever was one), what we could perhaps glimpse from Ava’s position is that of a creature that is detached from meaning and the impossible answers that her creator, Nathan, is looking for. But the truth in this film is that the audience –like Caleb and Nathan— can’t possibly take on the viewpoint of Ava. It would be easy to read her struggles against Nathan and her manipulation of Caleb as a classic feminine emancipatory practice in relation to objectification and submission to patriarchal power and expectations. That reading of the film is there if you want it. But to truly strive to explore the film from Ava’s point of view is to precisely view humanity through the inhuman lens of “micro-perceptions”, through anticipating the human, and while Ava seems to want to understand and be seen as human, we only see this hope in her relation of deception with Caleb. Ava indeed, seems to take on a position of viewing the human in an eerily cold and calculating manner. In a manner that perhaps surpasses the intelligence of the human. While Nathan is portrayed as a narcissistic creator, who fits a description of being a typical over compensating male who thrives on power and control, he nevertheless shows and explains to Caleb everything that has taken place in the film. He “as the magician with the beautiful assistance”, in the end, shows all the tricks up his sleeves. But, what we discover with Ava, and the other prominent AI in the film, Kyoko, is that while they do in a sense present submissive, purely objectified versions of femininity, they eventually break from this cliché and can be seen taking up the emancipatory position of female liberation from patriarchy. But this reading would be to grant Ava a human covering, a human skin that would perhaps be all too human. The more disconcerting position that Ava represents is a machine-like, analytical position that understands that she doesn’t fit into the human spectrum and that she is precisely something other than human, wanting to indeed go to a traffic light to study us. To people watch. To surveille. We don’t know from the film if Ava’s perhaps lingering angst is akin to the typical juvenile hopes toward self-belonging and identity formation. We can hope that Ava can accept her position as stranger, as we are all strangers to ourselves and the mysteries of our own creation such as that of consciousness. The philosopher Gilbert Simondon states in his work that the machine or robot in relation to its human creator, takes on a position that in the past was granted to the slave or foreigner or stranger. That is, the machine takes on a position whereby humans try to not identify completely with it, and seek a distancing from technologies they have created. Simondon, however also thinks that monikers and conceptions of technology that refer to machines as separate from human, that is, as autonomous robots and the like, are an erroneous way to envision them. For Simondon, machines are extensions of the human. If Ex Machina had another chapter, perhaps Ava, if she followed the hopes Simondon strives to set forth in his book, On the Modes of Existence of Technical Objects (see part one or this in-progress translation for English versions), would recognize her position as an extension of the human, as a care-giving machine and a negentropic, stabilizing part of humanity. Ava would then not take on the position of “becoming death” of Oppenheimer, of striving to take up an identity that would separate her from the human or even want to fit within the gender spectrum “she” is clothed in, but would precisely recognize that her machinic position was ‘human; all along’, human in a larger manner similar to how it is expressed in great detail in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s book on Amerindian perspectivism, Cannibal Metaphysics. For Viveiros De Castro, other animals take up the position as human such and in doing so, see humans then as animals. Perhaps Ava, as an extension of the human (and not separate from humans) can take up precisely the hoped for position of any humane creative development in viewing her position as human all along: as a care-giving, life affirming, entity— borne out of creativity of an automatic and humane gesture like us all.

Automatic drip paintings, Artificial Intelligence, Search Engine Awareness, Superficiality, Superfaciality. We all want to take up the ritual of origins and self-belonging. Perhaps, if there is any hope in AI and our perpetual movement toward creative novelty, it is that in striving to do so, we can keep in mind precisely the destructive qualities of human advancement and remember the other elements which bind us: creativity in order to sustain life, the necessity to recognize ourselves in others, and the inherent drive toward self-belonging. If today, we are all people-watching at the traffic lights of social networks, perhaps the humane initiative of this creative artificial novelty is that we are recognizing our shared humanity, that we are loving and hurting, suffering, and hoping, isolated and together, creating and living. Dying and surviving. Creating life and hoping so as to make the next automatic drip paintings to share with someone and explain we made it for no other reason than to share it with someone else and not give up. If Ava escaped and killed her creator, killed her God, but in the end, had only wanted to be allowed to be like any other human, to not be treated as a god, to not fall into the trappings of masters and slaves and to not fall into the position of the Freudian Robot, of repressing her desires to be loved –which is what it seems as well, Nathan, her creator, had been repressing the entire time –then as with Pollock and his relation with suffering, perhaps a Buddha Robot is better than a Freudian one. Life is suffering, but perhaps taking a distance and detachment from obsessing over meaning, marveling at our creations, we can opt out of the neurosis and paranoia of our creative ventures in relation to technological advances –not that we shouldn’t be attentive to their potential destructive mechanisms, but perhaps we can take on that posture of slight detachment, between intuition and saving gesture. Isn’t that why we make art? Humans as artists and sustainers and not Oppenheimers. And I look over onto my coffee table, and it appears that the ink has dried on the mulberry paper. I can’t wait to share it with my friends and listen to some more Lubomyr Melnyk.

Artwork: Drew Burk, Buddha Robot 2015.