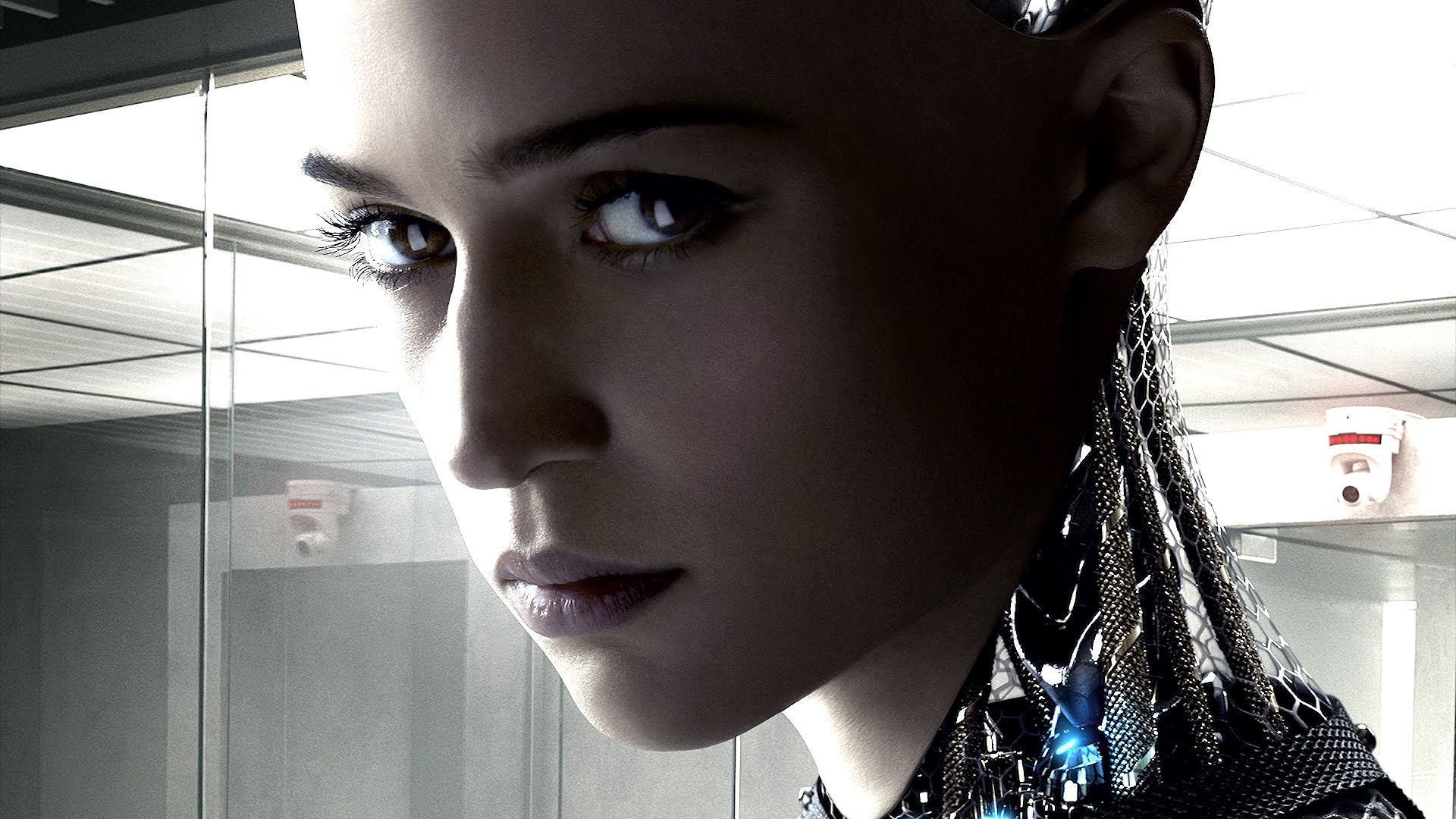

How Guattari’s Subjectless Action and Ethico-Aesthetics can be useful in post-digital culture and thinking with the film, Ex Machina.

This is the second of a two-part reflection on the movie Ex Machina (Alex Garland 2015). Part one is here.

“Savage voices and voices of the people, mad voices and infantile voices define the places where it becomes possible and necessary to write. Voices furnish the hermeneutic with its condition of production, that is, with the sites it occupies where it converts them to text.” Michel De Certeau, Vocal Utopias: Glossoalias.

“The mouth no longer speaks, it drinks the letter.” Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus.

“Since improvisation has become one of the methods of artistic expression, it turns out to have not been a dream. It is just something like a pathway into a dream. Intuition comes from perspective. An intuition stands up in a single stroke, and then creates a fringe.” Min Tanaka, Machinic Eros: Writings on Japan.

To further explore both the notion of artificial intelligence, its relation to consciousness, as well as its relation to the production of art, it can be useful to return to the groundbreaking work of Félix Guattari and his conception of subjectless action. Guattari reminds us that, in the realm of language, we can always replace any pronoun with “it”. [1] He immediately reminds us of how we can dig into the molecular and de-territorialized nature of machinic utterances in recognizing that ‘It’:

. . . does not represent a subject; it diagrammatizes an agency. It does not over-code utterances, or transcend them as do various modalities of the subject of the utterance; it presents their falling under the tyranny of semiological constellations whose only function is to evoke the presence of a transcendent uttering process; it is the a-signifying semiological matrix of utterances –the subject par excellence of the utterances – in so far as these succeed in freeing themselves from the dominant personal and sexual significations and entering into conjunction with machinic agencies of utterances. [2]

Guattari comments on thinking the “it” from a position that frees itself from the over-coding of utterances. This leads Guattari to see the potential for a-subjectifying utterances to shed any attachments to a particular subject, a “he” or “she”, a “masculine” or “feminine”, in effect, to the binaries of subject and object. However, in freeing themselves from the dominant personal and sexual significations, as the utterance par excellence, “it” nevertheless has to contend with the a-signifying utterances’ relation to de-territorialization, as well as the relentless encoding and overcoding of meaning. Guattari refers to the latter as the despotic formalism of a writing machine. That is to say the official writing machine, where the “primitive” writing machines relinquish themselves to the control of what he refers to as “the signifying machine of double articulation”.

In falling under the control of the double articulation of the official writing machine, Guattari states that a power machine cannot be separated from the nomadic military machine. It is here that we have what would appear to be the dead-end of a-signifying [3] figures of expression. That is to say, we have the introduction of a grammaticality: The letter castrates the voice by dividing speech up into phonemes, and the voice mutilates the diagrammatic potential of an arche-writing by re-arranging words according to meaning. [4] The desiring utterances and intensities, he continues, end up finding themselves already then arranged around a world governed by mental representations and what he will call a fictive subject. This is not without extreme interest for us here. A fictive subject is one whose power is derived from rendering it powerless. But perhaps, all is not lost for the subjectless, a-signifying utterances. Whereas at the level of the subject, that is the individual and the person, the pronominal “it” and arche-writings find themselves re-territorialized in the form of a fictive and powerless subject, and within a grammaticality that no longer allows for the flow of a-signification. Guattari insists that the nullifying desire of the fictive subject can still find a means of semiotic escape via the a-signifying figures of expression. This is achieved by way of beginning new desiring machines whereby reflexive consciousness can “abolish itself in the paroxysm of joy of a machinic consciousness that has truly broken all territorial moorings.” [5] The a-signifying machines, for Guattari, find themselves outside the reach of what he describes as the “impotentizing attacks of reflexive consciousness” [6]. This leads Guattari, in a somewhat ironic manner, to find these new potentiations within the act of “making conscious”. If Descartes’ cogito is considered a potential escape from a-subjectivation into a retrieval of the so-called thinking subject (the I that thinks), for Guattari, this escape is still a fiction; and more specifically, a machine-fiction. [7] Following Guattari’s line of reasoning, making conscious involves such an intensity and degree of de-territorialization that it, in essence, becomes detached from all reference points. And this brings us back to our discussion on the future of the unconscious and the digital in regards to Lydia Liu’s comments regarding artificial intelligence and post-digital communication, where we find ourselves confronted with either the Freudian Robot or the Buddha Robot.

At the extreme limit of “making conscious”, where Guattari sees us at the extreme limit of de-territorialization, we discover that consciousness is not faced with the binary of opposition between being and nothingness, but is precisely both all and nothing. From then on, there are only two options for Guattari that begin to sound like Liu’s comments of the Freudian Robot or the Buddha Robot. Guattari states that within this black hole of de-territorialization consciousness has either the option of asceticism or castration. Or perhaps a third option: a new economy of de-territorialization with super-powerful sign-machines capable of coming into direct contact with non-semiotic encodings. In the case of Ex Machina, Ava could be much more than a mere simulacrum of the human or its evolutionary progress. More interestingly enough, she could be thought of as a new economy of de-territorialized paryoxmal joy of a consciousness that is both all and nothing; a sign-machine that is capable of coming into direct contact with non-semiotic-codings, that is, a human-bartleby machine of collective intelligence, of micro-expressions and artistic hope. Opposed to the I-Ego economy, Ava could also be the incarnation of a molecular a-subjective, subjectless humanity. A Buddha robot? A Freudian Robot? A human(e) robot…

Guattari asks another important question in his later work, Chaosmosis (read the first chapter here) that can be useful for us here in thinking our relation to social network culture and artificial intelligence: “How can a mode of thought, a capacity to apprehend, be modified when the surrounding world itself is in the throes of change?” Indeed, if we continue thinking this provocative question put forth by Liu’s book on the future of the unconscious in relation to the human’s machinic extension with artificial intelligence, then Guattari’s attempts at a capacity to apprehend and modify a mode of thought within a tumultuous time of accelerated change is as prescient as ever. Guattari’s concerns and hopes bring us to the necessity of rigorously critiquing our relations to the past. Is there a manner, in striving to think within the throes of change as Guattari was striving to do himself, where we can take on a perhaps a uchronic position toward the past? That is to say, to think a parallel past that didn’t take place. A thought experiment that provokes an alternative future-past in order to think with and against Liu’s provocations of the Freudian Robot, where the Freudian Unconcious is precisely replaced with another ethico-aesthetic practice. This was Guattari’s hope. An attempt to move away from a past where “The Freudian Unconscious is inseparable from a society attached to its past, to its phallocratic traditions and subjective invariants.” [8]

So, how do we move beyond the past? How do we move past the phallocratic traditions and its subjective invariants? In the aftermath of emancipatory politics and within a current age of media deliriums, where we are all allowed to scream and cry our outrage and become the users and producers of media and the illusions and dreams of detournements of Debord have been given to us all within the virtual-actual spaces of social networks; or at least, keeps us chained to a Freudian unconscious (a Freudian Robot). The question, Ex Machina then brings to the forefront, is more than a simple question of Feminist emancipatory politics, it’s a position outside of striving perhaps to take on the compulsion of consumption today: the consumption and compulsion to Identify, to share Identification, and to consume Identity. Then, how can we begin to grasp a capacity to think within the ever-changing landscape today in a manner where we take up a mode of consumption that would be akin to a capacity and novel mode of thinking within our current landscape of post-digital culture?

As Michel De Certeau reminds us, there were once certain methods and modes of reading where what was necessary was an art of the ruminatio, of “slow reading”, or a slow consumption that is a manner of “swallowing” and “digesting” the texts [9]. This manner of reading dates back to the 12th century and it has a direct relation to questions of memory, knowledge retention, that perhaps for us today, can be a useful measure for thinking and pairing De Certeau’s historical analysis of this process. To think how we can consume the identities, image-text modes of exchange, and consumption in order to begin to think types of novel, ethico-aesthetic practices of “slow eating and slow reading” of our cultural and digital image-text utterances. This entails us not purely to “chew”, which is to “ruminate”, but also “swallow” and “digest” them in manners that allow, shall we say, for healthful digestion of knowledge, and perhaps more importantly, emancipatory, humane modes of exchange. Social networks remind us all too well that our identities themselves have become at once artistic and performative processes and simultaneously mere goods of exchange. If this is true, then for us to reclaim our identities and a “second of self” as Wallace Stevens speaks of in regards to the power and proper reading of poetry, then this poetic reclamation of identity against mere assimilation within the exchange value of semio-capital is a good place to start. As Bifo Berardi reminds us, poetry is perhaps one of the only expressions that doesn’t fit into capital manipulation. [10] Poetry as the insolvency of language.

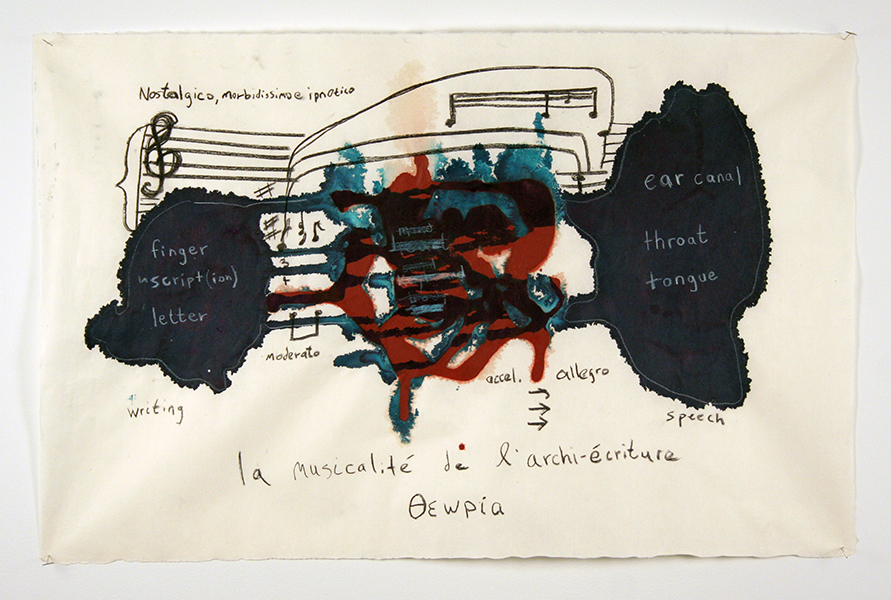

If Ava puts on a different dress that is identical to the one seen worn by the artistic image of the woman in the Klimt painting (which is interestingly enough a portrait of Wittgenstein’s sister [11]). Perhaps it is fruitful to view this poetic gesture as the aesthetic identity of self-creation or self-reclamation; moving outside from the painting of a fixed image-identity, which is parallel to the identities we create online and where the identities are merely assimilated into code and the echo chambers of noise. Thus, Ava does not need to identify with humans as such, but rather with the creation of artwork itself. In this way, Ava becomes a human as artwork in progress. Like us all: our identities always already in flux and in the end, containing the potential ethico-aesthetic practices of self-care. If poetry is, for Berardi, perhaps one of our only hopes in staving off complete exhaustion and subjugation to capital, then within social network shared utterances, a movement from (information) noise to poetic musicality, to a machinic glossolaliac speech (improvisational digital speech (as) music as shared prayer) is perhaps a place to begin thinking our shared potentials for reclaiming speech in the post-digital era. De Certeau calls these spaces Vocal Utopias [12] and I’m writing at great length on this topic for another project. But what Ex Machina and these blog reflections have helped to remind me of is the necessity to create various modes of poetic articulation (in this case, in the form of ink-paintings on mulberry paper) and to recognize the necessity and capacity for creative improvisation [13] in art and theory practices. The poetic movement between intuition and humane gesture. A musicality of arche-writing. De Certeau explains to us that “For the glossolalist, though, the starting point that calls forth the song is not even a line: it is only an ‘air’ of beginning.” [14] A tracing of shared poetic-glossolaliac voice that we all share within our social network exchanges. As Guattari reminds us with his exuberance for autopoeitc processes akin to Jazz and Rap as well as the return of machinic orality in post-media culture: “Orality, morality! Making yourself machinic […] can become a crucial instrument for subjective resingularization and can generate other ways of perceiving the world, a new face on things, and even a different turn of events.” [15] I leave the reader with one more improvisational artwork and thank them for entertaining my reflections on the film and my poetic attempt to begin once again.

Drew Burk, Notes on Vocal Utopias: Musicalité de l’archi-écriture, 2015.

Drew Burk, Notes on Vocal Utopias: Musicalité de l’archi-écriture, 2015.

NOTES:

[1] Félix Guattari, trans. Rosemary Sheed, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics, Peregrine Books, 1984, p. 135.

[2] Ibid.

[3] For more on Guattari and a-signfying semiotics cf. Gary Genosko’s paper A-signifying Semiotics in The Public Journal of Semiotics II(1), January 2008, pp. 11-21: http://journals.lub.lu.se/ojs/index.php/pjos/article/view/8822/7920.

[4] Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics, p. 136.

[5] Ibid. p. 137.

[6] Ibid. p. 137.

[7] Ibid. p. 137.

[8] Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis: an ethico-aesthetic paradigm, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis, Sydney, Power Publications, 1995.

[9] Cf. Michel De Certeau, Ed. Luce Girard La Fable Mystique: Tome II, Editions Gallimard, Paris, 2013, p. 210.

[10] Cf. Bifo Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, Semiotext(e), 2012.

[11] I would like to thank Trent Knebel for pointing this illuminating fact out to me.

[12] Cf. Michel De Certeau’s Vocal Utopias: Glossolalia in Representations, No. 56, Special Issue: The New Erudition (Autumn, 1996) pp. 29-47.

[13] As Min Tanaka states in dialogue with Félix Guattari, “Generally, freedom cannot be taken into account if some fiction precedes it. One has to adopt a perspective as an ensemble of thoughts, that is, an improvisation which always exists “between” them. One might understand that playing more freely or anarchically is an improvisation, yet nothing proceeds well without recognizing what enables improvisation. Since improvisation has become one of the methods of artistic expression, it turns out to have not been a dream. It is just something like a pathway into a dream. Intuition comes from perspective. An intuition stands up in a single stroke, and then creates a fringe.” Cf. Félix Guattari’s Machinic Eros: Writings on Japan, Univocal: Minneapolis, 2015 p. 51.

[14] Michel De Certeau, Vocal Utopias: Glossolalia in Representations, No. 56, Special Issue: The New Erudition (Autumn, 1996) pp. 29-47.

[15] Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis: an ethico-aesthetic paradigm, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis, Sydney, Power Publications, 1995 p. 97.