Before the establishment of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), displays at museums of nature, science and culture involved their preparation and arrangement in glass boxes by those who had never seen the subjects in their actual habitat and who had little interest in acquiring related ecological or cultural information.1

From its beginning, however, the AMNH was interested in a different strategy for its displays by hiring artists to collaborate with museum scientists working in the fields of mammalogy, ornithology and anthropology. The museum was aiming to convey scientific knowledge about nature and culture not just to specialized scientists and their students but also to the general public who, at least in New York, consisted increasingly of new immigrants and their children.2 The establishment of the AMNH involved fundamental shifts in the understanding of the function of museums among museum professionals in USA. “As the twentieth century progressed, the museums were receiving a new competition for the attention of the public from zoological gardens and traveling menageries, from photographic illustrations, and finally from motion pictures themselves. The layman [sic] had come to be fairly familiar with what he might expect to find beyond the horizons.”3 These transformations began as museums started to take visitors into consideration for the design of display systems. This consideration moved away from the representation of nature in an exhibition to its actualization or, simply put, its fully-realistic presentation.

The shift in museum display design from the taxonomic to the virtual has a striking similarity with the movement of cybernetics from the first to its second wave. First wave cyberneticians focused mainly on ideas and practices that separated information from matter and organized it as a common code of exchange. They regarded the relationship between the observer and the system as mutual but nevertheless considered the two as separate entities. The second wave, as noticed by N. Katherine Hayles, “grew out of an attempt to incorporate reflexivity into the cybernetic paradigm” and “account for the observer in the system.”4

The establishment of the AMNH demonstrates a major shift in the presentation of scientific information as well as changes of attitude amongst museum managers regarding the institution’s social role in the twentieth century. The AMNH, from its inception, had taken the view of George Browne Goode—the then-head of the National Museum of Natural History in England—that museums, instead of being a repository for the preservation of scientific specimens, should “cultivate the powers of observation” in the service of education.5 On the other hand most museum managers who had risen up to their positions from various related scientific fields were weary of appealing to the lay public and more interested in upholding the prestige of their scientific museums than competing with popular entertainment forms like panoramas and movies. As Benno Wendolleck, an assistant at the Dresden Natural History remarked in a review of the habitat groups at Chicago’s Field Museum, “[t]hey do nothing for the understanding of nature, nor will they educate the public in art.”6 However, there were others like Otto Lehmann, the director of the Altona city Museum who admired the AMNH approach to display making, and for whom “the museum was a place that taught people how to see, and how to look thoroughly at objects, to take their meaning and to appreciate their beauty.”7 He argued that the most basic level of mental intake is that of raw sense perception and an intuited sense of being in the world. He considered the creation of such environments a necessary step for developing higher levels of comprehension. To Lehmann, it was important that the display be both realistic and phenomenologically charged. These conditions rendered abstract scientific information comprehensible by masses at the perceptual level. Thus, Chicago’s Field Museum and the AMNH chose a new direction away from the old European model, one that transformed the way the Museum impacted its visitors and achieved its pedagogical objectives.

However, the resentment towards new display methods at museums of science, nature and culture wasn’t just a cultural difference between one Europe protective of the continent’s scientific heritage versus the United States wishing to attract large crowds to their scientific and cultural institutions. There were influential American critics of the fully realistic model of display who were ambivalent about the pedagogical versus scientific missions for the museum and, similar to European museum professionals, wanted to prevent museums from drifting away towards what they conceived as popular entertainment.

Those who argued against fully realist displays in the United States based their opinion mostly on the impracticality of deploying dioramas out of a fear that attempting to immerse the audience in the museum would fail due to the limitations of available technologies that could successfully transform the space into what the exhibit was aiming to present.

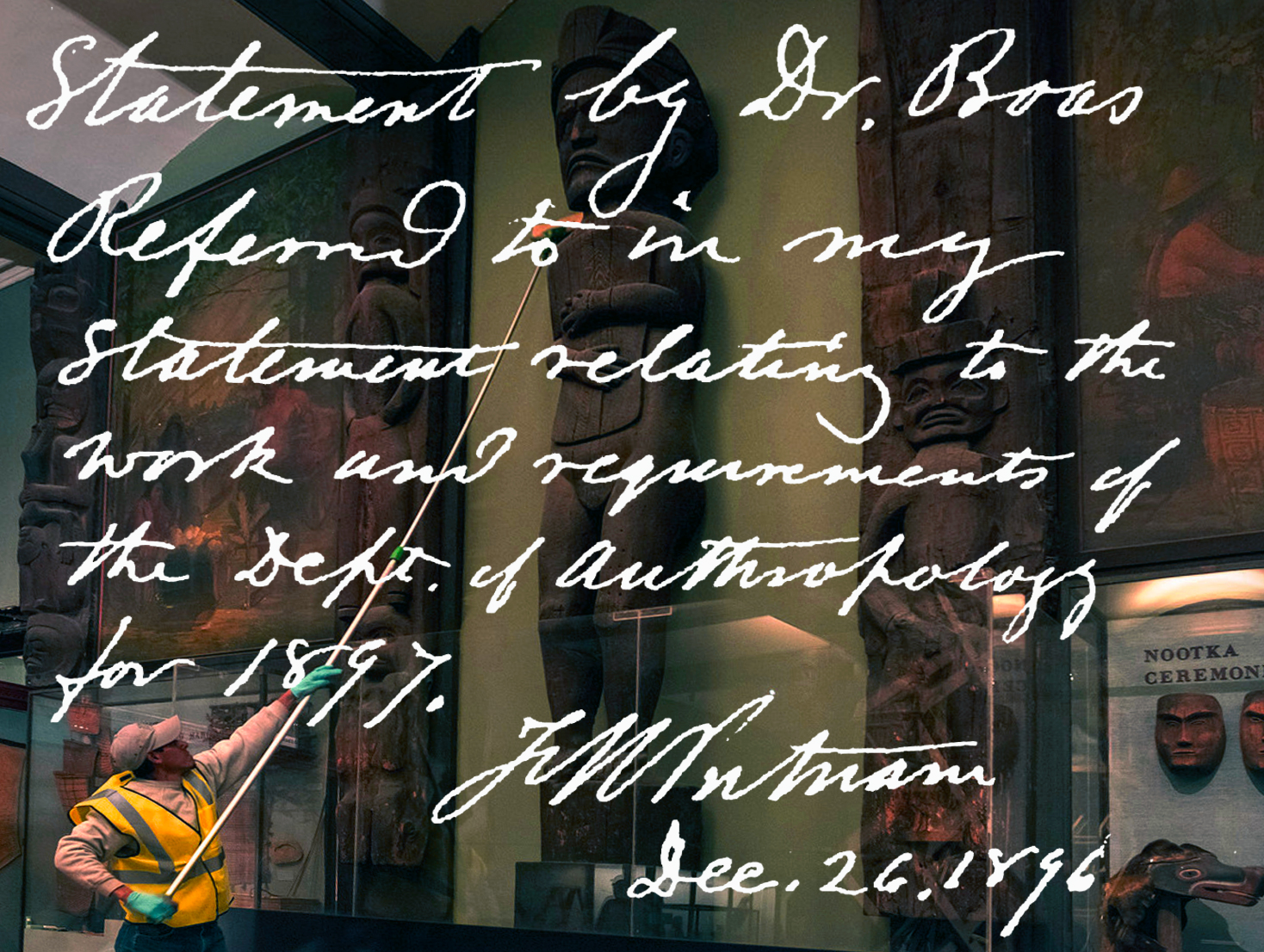

Respectively, Franz Boas’s words in this never-published-before letter from 1896 as the curator of ethnology at the AMNH to Frederick Ward Putnam, the Museum’s head of the Anthropology Department, highlights the thrust of these arguments. The letter begins with recommendations as to how a museum should perceive itself and approach its general mandate. For Boas, any attempt to transpose the visitors to a different place and time is already a failure mostly due to the physical limitations of the museum site. Boas instead insists on the need to present all subjects in scaled down models and to draw a conscious attention on the plasticity of the materials used in their making. This way, visitors would not get lost in their amazement at displays’ verisimilitude, forgetting the institutional frame of the museum as a self-conscious pedagogical site of their experience.

This, of course, was a lost battle. During the fifteen years between Boas’s correspondence, which helped shape the Northwest Coast Hall at AMNH, presenting life and artifacts of Haida people on the West coast of British Columbia—an exhibition hall to which the letter makes direct references—and the approval of Carl Akeley’s plan for the construction of the African Hall, a fully realistic and self illuminating set of habitat dioramas presenting African nature in a dark hall, AMNH managers would transform their institutional outlook, for better or for worse, to the point that Boas’s warnings would become exactly what they not only desired to accomplish but were able to do so thanks to the advancement in both photographic technologies and museum display techniques.

Department of Anthropology

New York, November 7, 1986

Prof. F. W. Putman,

Dear Sir,

You have informed me that the Ground Floor (Basement) of the new West Wing of the Museum when completed will be devoted to the display of the Ethnological Collections. It becomes, therefore necessary to prepare plans for their installation and I beg to submit to your judgment these following considerations. Before making detailed plans for cases and for installation it seems best to lay down certain general principles which the arrangement of the collections must follow.

The two prime objects of the Museum being, First: Public instruction, and Second: Advancement of science, the interests of both must be equally borne in mind. These two ends are attained, the first by the Exhibition Series; the second, by the Study Series.

In the Exhibition Series every single specimen must be instructive either through its characteristics or through its associations. Moreover, since it is our endeavor to instruct the general public rather than the special student, the arrangement must be designed by appropriate methods of display to attract the attention of the visitor to certain important features of the collections. From these considerations I draw two conclusions:

First: All specimens that do not serve to illustrate certain facts or points of view must be excluded from the Exhibition

Series.

Second: Enough space must be given to each specimen in the Exhibition Series to be seen individually and it must be accompanied by a full descriptive label which calls attention to the point of view which the specimen is intended to illustrate.

Third: The objects which are intended to illustrate leading points of view must be exhibited in the form of groups or by other appropriate means which attract at once the eye of the visitor. I believe that in this last point lies the fundamental

function of groups. No other means can be devised to attract the visitor so forcibly and to bring out certain points so clearly as a group. I may illustrate this by an example: We have a figure showing the method that the Indians of Alaska employ for preparing cedar bark. In the case next to this group is a collection of all the implements used in this work. I have taken notice that on Saturdays when the public leave the Lecture Hall, they invariably look at the group and then turn to the adjoining case; and I find by their remarks that I have succeeded in reaching the end that I had in view in the arrangement. The visitors discuss the uses of the implements, comparing them to those they see in the group, and

they stop to read the labels.

There is one great danger in the use of groups, namely that the element of impressiveness that they possess may overshadow the scientific aim which they serve. There are three noble cases which must serve us as a warning, namely: The Museum at Bremen has arranged groups of this description on a very large scale including whole houses, groups of people in various attitudes, etc. The same has been done in an exhibition at Hamburg, and at Prague in the Holub Collection. In all these cases the instructive effect is simply lost, partly because it has been impossible to preserve the continuity between collection and group, but principally because the group is arranged for effect, not in order to elucidate certain leading ideas.

Even the artistic effect has suffered by this attempt at impressiveness. One of the elements of artistic effect is unity of concept. Only when the concept is brought out clearly so that it appeals at once to the visitor can there be an artistic effect. If a number of figures are placed in one group whose actions although allied have no unity of purpose the effect is very much weakened because the attention of the visitor is distracted from one point to the other and because there is no underlying concept that appeals to him [sic]. As soon as he must ask, “What is the figure doing?,” one half of the instructive and artistic effect is gone. The whole must appeal to him at once. Therefore it is much better not to undertake the representation of complex groups but to adhere strictly and rigidly to the principle of representing one thing only in each group and to endeavor to bring that one thing out as strongly as possible.

A second point that I observed in studying the effect of groups is the following: It is an avowed object of a large group to transport the visitor into foreign surrounding. He is to see the whole village and the way the people live. But all attempts that I have seen at such an undertaking have failed because the surroundings of a Museum are not favorable to an impression of this sort. The cases, the walls, the contents of other cases, the columns, the stairways, all remind us that we are not visiting an actual village, and the contrast between the attempted realism of the group and the inappropriate surroundings spoils the whole effect. The larger and the more complex the group, the more conspicuous the failure in attaining the desired end; for the larger the group the more it is necessary to allow ample space around it so that it can be seen from a distance, and the more general the view that the visitor is intended to observe the more a background will appear necessary. This last cannot be made in a Museum, because the conditions of light and the architecture of the Museum give no opportunity of attaining satisfactory result.

It may be well to exemplify this: Supposing we wanted to illustrate the life of the Indian of the Plains by means of a group showing a village. A number of tents, women doing their home work, men gambling and some returning scouts, might suggest themselves for such a scene. All of this could be placed in a space of say 30 X 25 feet. In order to see such a group to advantage the visitor must stand at least 15 feet away. If the group were in the middle of the Hall, without background, the space required would be 60 X 55 feet or 3300 square feet. But in this manner no favorable effect could be had. We should have a heterogeneous scene crowded into a space much smaller than it would naturally occupy, and on account of the surroundings of the Museum Hall the general effect for which we are striving would not be attained. In order to set off such a group to advantage it must be seen from one side only; the view must be through a kind of frame which shuts out the line where the scene ends; the visitor must be in a comparatively dark space, while there must be a certain light in the objects and on the background. The only place where such an effect can be had is in a Panorama Building were plaster-art and painting are made to blend into each other and where everything not germane to the subject is removed from view. It cannot be carried out in a Museum Hall.

If on the other hand I divide the Indian group into three separate groups the artistic and instructive result will be far better and may be attained with great economy of space. These may be one group of women doing housework; one of gamblers; and one representing a scout on horseback. They will measure rather less than 12 X 12 feet each or including an aisle of 7 feet, 64 X 26 feet or 1674 square feet. This is only one half of the large group and in a shape that is much more advantageous. Furthermore the expense of the large case will be very much greater than that of three small cases.

There are, therefore, three reasons that make it desirable to confine the work of making groups to smaller ones:

First: The educational object of a group is to call attention to certain aspects of native life. This purpose is best subserved by making each group illustrate one single point of view only.

Second: The artist effect of small groups is much better than that of large groups. All previous experience shows that large groups in Museums will be failures.

Third: Economy of space and of expenditure combined with the best possible effect is attained by small groups.

It may be well to add a remark on the amount of realism that it is desirable to attain. No figure, however well it may have been gotten up, will look like man himself. If nothing else, the lack of motion will show at once that it is an attempt at copying nature, not nature itself. When the figure is absolutely lifelike the lack of motion causes a ghastly impression such as we notice in wax figures. For this reason the artistic effect will be better when we bear in mind the fact and do not attempt too close an approach to nature; that is, since there is a line of demarcation between nature and plastic art, it is better to draw the line cautiously than to try to hide it. Thus the ghastly effect of which I spoke will be avoided. Therefore all figures should be made so that they are shown not in the height of action but in a moment of rest; the color should be an approach to the real color but not an attempt at an absolutely accurate copy of skin texture and color, particularly as the conditions of the light and of material make it impossible that the color of a figure should appear the same at all times and as seen from different points. Lastly, scattered hair should be indicated by paint (or by plastic work) not by actual hair.

From those points of view I have formed the following plan for the Ethnological Exhibition Series:

The central aisles of the two halls—the one in the North Wing and the one in the West Wing—are to be reserved for groups, while the sides of the halls will serve for placing the collections. So far as feasible each group will be placed as to bear upon the contents of the adjoining cases. No groups are to exceed in size 12 X 12 feet, or in exceptional cases 12 X 15 feet. Many will be of smaller size, so that a series of about eight or ten groups may be placed in the central aisle. Single figures or busts, such as the objects may require, will be placed in the cases containing the collections. Personal ornaments must be shown on busts or hands or legs; garments should be draped on figures; and methods of transportation and the use of implements should be shown in this manner.

Another important feature of the exhibit must be considered in planning the new cases is that of primitive architecture. On the whole I think it is impossible to show full size native habitations because they take such a vast amount of space without being thoroughly instructive. We can and ought to have a full size teepee and other small habitations, but by far the majority can be better shown by means of models about 1:20. On such a scale all the details of construction and the arrangement of the village can be shown. I am planning at present about thirty models of this kind for North America and fifteen for the South Sea Islands. All of these should stand in cases similar to the cases used for bird groups.

The new Hall is to contain three large collections: The Sturgis collection, the Lumholtz collection and the Eskimo collection, and these will nearly fill it. The Sturgis collection will occupy the whole North side of the Hall, and the other two collections, together with the miscellaneous collections that we have will fill the remainder of the Hall. This will leave the central aisle for a series of group cases. I think it will be advantageous to give four or five groups to the Peary collection; two to the Lumholtz collection; and one to the Sturgis collection. In this way the hall will be filled comfortably.

The old hall will then be available for the Northwest Coast collections which will fill it. The following groups will take up the central aisle: (1) Domestic Scene. (2) Scene on the Beach. (3) Ceremonial Dance. (4) Incantation by a Medicine Man. (5) Skin dressing.

In laying out plans for the installation I assume that the new Hall will be opened in the Spring of 1898. The preparation of the whole exhibit is a matter of considerable expense of money and time, and it will be hardly possible to have all the preparations completed by the time named. Therefore we must lay our plans so after the opening there will be no need of moving the collections, and the new exhibits can simply be added in their proper places. It would seem best to prepare first of all those exhibits which will make clear the idea of the whole arrangement and then add the details gradually as time and funds will permit.

The principal expense to be incurred consists in the preparation of casts, busts, models, stands of various sorts on which specimens must be exhibited, and in the preparation of the groups. But these, I think, can be kept in reasonable bounds, but we cannot dispense with them. Arranging ethnological specimens, such as dress, ornaments, etc., without them would be exactly the same as Prof. Allen should hang unmounted skins in his cases or Prof. Osborn should leave his specimens imbedded in rock and unmounted. In arranging the collection I shall need, so far as I can judge at this time, the following objects:

THE NEW HALL — Sturgis collection:

- 15 busts for exhibiting the methods of wearing ear ornaments, nose ornaments, hair ornaments, ornaments for the forehead, necklaces, breast ornaments; and for showing methods of tattooing.

- 20 arms for showing bracelets;

- 3 whole figures for showing dress and ornaments, and the use of masks.

Lumholtz collection: 4 figures for showing dress and ornaments.

- Peary collection: 1 figure for showing the use of the bowdrill.

- 2 figures for kayaks.

Miscellaneous collection: 1 figure of North American Indian.

- 1 bust of North American Indian

THE OLD HALL

- 1 figure illustrating methods of transportation by land.

- 4 busts showing the use of head ornaments.

THE NEW HALL — Models illustrating Primitive Architecture.

- 8 models of Eskimo habitations.

- 4 models of South Sea Island homes.

- 2 models of Mexican habitations.

- 5 models of North American lodges.

THE OLD HALL – Models illustrating Primitive Architecture.

- 3 models of houses.

- 1 model of subterranean lodge.

- 2 mat lodges.

I shall also need a number of small groups showing methods of setting traps, fishing hooks, etc.

In this I have not included the work on the regular groups. It is evident that all this work requires the constant services of competent men; and I do not see how we can hope to make a satisfactory installation unless the necessary technical work is to be placed on a permanent basis.

Prof. Allen and Prof. Osborn are having their exhibits prepared in their technical departments, and it is just as indispensable that your Department should have a permanent technical department connected with it. It is true that we have had two men doing this work right along, but there has been so much uncertainty as to the permanence of their employment that it has been very difficult to lay any definite plans; and frequent changes in plans are necessarily uneconomical. If the other Departments find the services of the technical department indispensable right along, how much more so we, at a time when we have to install a whole new wing.

Finally a word in regard to the collections: It must not be understood that our collections are in any way nearly complete.

The two collections from Alaska and the Sturgis collection are very good in their way, particularly in so far as they contain many beautiful pieces; but both need completing very badly. In the collections from the North Pacific Coast, the whole region from Southern Island to Vancouver Island is unrepresented. In the Sturgis collection all the common everyday things are missing. The Peary collection gives us a very good start on Eskimo material, but no other tribe of Eskimo is well represented. Our North American Indian material is very unsatisfactory, and other continents are hardly represented at all. Under these circumstances the collections must be considered as needing additions very much indeed and I hope that a permanent growth may be possible.

Yours very truly,

(signed) Franz Boas.

NOTES