“When you maintain a top-down view of the world, everything seems bottom-up.” -Mongolian proverb

Matteo Pasquinelli’s June 2019 e-flux article “Three Thousand Years of Algorithmic Rituals: The Emergence of AI from the Computation of Space”[1] is a hurried attempt at providing a deep historiography of algorithms, beginning with the topology of Hindu culture via examining the schematic geometric composition of the falcon in the Agnicayana ritual. Parsing Frank Rosenblatt’s Perceptron[2], an early photoreceptor-machine capable of self-sufficient deep learning, the author asserts that “algorithms are among the most ancient and material practices, predating many human tools and all modern machines.” He then reflects on “Vision Machine,” a concept coined by the philosopher Paul Virilio, and predicts its disappearance in the era of artificial intelligence and industrialized vision, concluding that topological transformations similar to those proposed by Perceptron are being grafted into a technique of memory. Accordingly, the Agnicayana ritual, the Perceptron, and today’s AI systems are not only examples of self-computing spaces and emergent algorithms but the erasure of the Marxist notion of labor.[3]

Despite providing interesting and somewhat related anecdotes, Pasquinelli’s arguments vacillate between the familiar grammars of structuralism and poststructuralism without providing brand-new insights into either history or ontology of algorithms. Beginning with the construction of geometric forms and cosmic entities qua the Agnicayana rituals, he traces the genealogy of the subject, rooting them “among the most ancient and material practices, predating many human tools and all modern machines.” By tying geometric and social segmentation into this algorithmic impulse, the author defers to Ernst Kapp’s now-defunct model of “organ projection”: that every tool, immaterial or not, is a continuation of the body’s organs. In this case, algorithms reify the operative, sense-making tool that extends the computational organ per excellence: the brain thus why he uses the figures of the “Organization of the Mark I Perception.”

This view also pays an indirect lipservice to social constructivists by tracing the roots of scientific and rational developments, often springing from alien and paradoxical contingencies, in historical, social and cultural practices. This kind of attitudes towards material and technological developments are hallmarks of poststructuralists, who often search for the casus belli of a phenomenon in discourse, never the other way around.

To focus further on the text, it is important for us to understand Pasquinelli’s definition of algorithms:

(1) an algorithm is an abstract diagram that emerges from the repetition of a process, an organization of time, space, labor, and operations: it is not a rule that is invented from above but emerges from below; (2) an algorithm is the division of this process into finite steps in order to perform and control it efficiently; (3) an algorithm is a solution to a problem, an invention that bootstraps beyond the constrains of the situation: any algorithm is a trick; (4) most importantly, an algorithm is an economic process, as it must employ the least amount of resources in terms of space, time, and energy, adapting to the limits of the situation.[4]

Since this definition relies heavily on the empiricism provided earlier in the text regarding the Hindu rituals, one would expect more rigorous research from the author about these rituals and other examples which can justify his primary assertion about their connection to algorithms. However, we are left to trust the author’s top strictly top-down view of his strictly bottom-up hypothesis, a part-structuralist and part-poststructuralist understanding of algorithms. This is not to say that algorithms cannot emerge from material practices and rituals, but not all follow the same and singular developmental trajectory scripted by the author in this text.

Furthermore, the author’s political thesis regarding cognitive and immaterial labor, despite its Marxist interface, is devoid of real Marxist vigor apparent in the works of other authors such as Bernard Stiegler who have previously dealt with the same topic. The text contends that “[t]he Agnicayana ritual, the Perceptron, and the AI systems of self-driving vehicles are all, in different ways, forms of self-computing space and emergent algorithms (and probably, all of the them[sic], forms of the invisibilization of labor).” However, Stiegler’s work carefully demonstrates that while the internet and automation’s increasingly self-annotating techniques offer potentials for emancipation, practices like metadata collection, data mining, and the assemblage of social graphs impose capitalist proletarianization by exteriorizing human experience onto digital platforms, resulting in the loss of savoir-fiare, or what he calls “knowledge of how to make do.” For Stiegler, a new digital culture-to-come must collectively individuate, producing “new moral beings” who are “de-proletarianized”. This future points toward the commons and philia.[5] Pasquinelli, however, lapses into mere cultural prognosis, reminiscent of both structuralism and poststructuralism, describing a situation for which he provides no remedy.

Based on contemporary knowledge, we already know that machines can no longer be considered as the extensions of bodily organs—as previously conceived by the 20th-century anthropologists and media theorists such as Arnold Gehlen and Marshal McLuhan—but agents in a field of techniques and parts of a network of pathologically distorted relations. Furthermore, it is not solely due to the algorithms’ spatial logic that self-computing spaces facilitate a collective closure with post-WWII cybernetics/second-order cybernetics.[6] There is, in fact, an interwoven line between second-order cybernetics, Predictive Processing, and algorithmic governmentality. As the second-order cyberneticians dealt with the “recursion of recursion,” their work foretold of how algorithmic modes would engage in predictive coding. Such generative and predictive models account not only for the Helmholtzian principle of “perception-as-interference,” but also for the interoceptive contribution of the body and environment in structuring sensorimotor interactions.[7] Predictive coding is a leading theory of how brains perform probabilistic inference. Similarly, there are a number of algorithms described by the term “predictive coding”; linear predictive coding has a long and influential history within the literature of signal-processing.

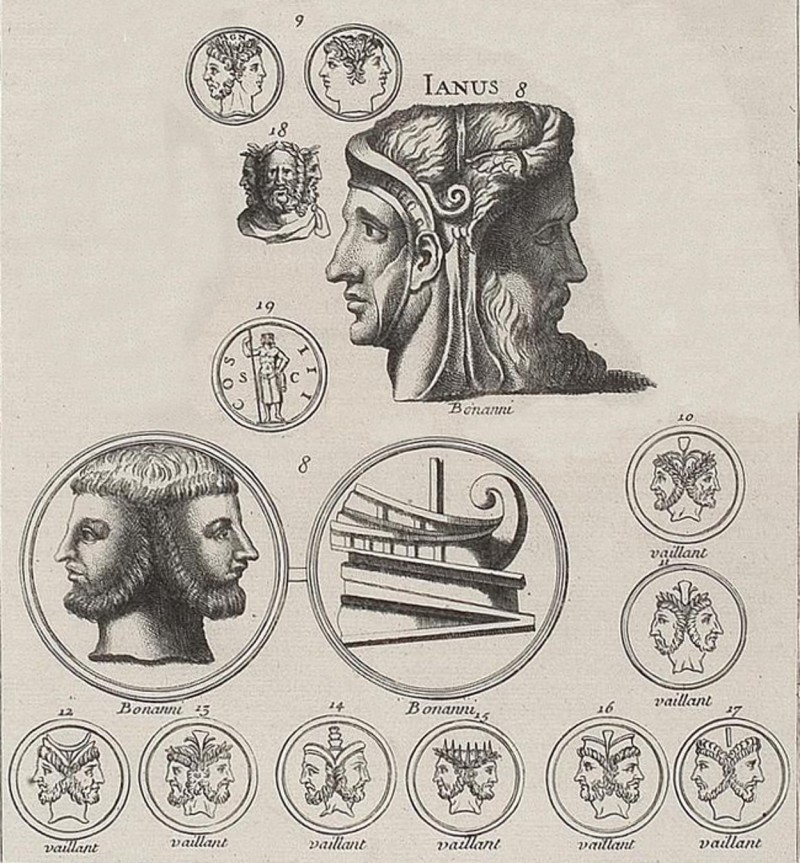

Pasquinelli foregoes the biomorphic notions of machine-learning to privilege topological “bottom-up” spatial dispositions. Thus, the nexus of the author’s structuralist argument is the centrality of “computational geometry,” as if any structure could stand without engaging in environmental feedback. As Reza Negarestani evinced in a lecture on Deleuze and Guattari’s turbulent flows, all machines are Janus-faced.[8] Regardless of what the scholastic humanities cultivate through selective top-down or bottom-up genealogies, they fail to capture the qualitative registers of General Intelligence, choosing to overextend polemics for the sake of spectacular techno-political “resistance.”

The author states that “[l]ogical forms that were made out of social ones, numbers materially emerged through labor and rituals, discipline and power, marking and repetition.” The essay begins with a quote from the late Paul Virilio, who, himself, was misinformed about the steam machine as a marker of the imperceptible and complex branches of science, as it introduces probability, statistics, and optical motion into the discourse on reticulated screens like cinema, all of which his account of the “vision machine” ignores:

Now that they are preparing the way for the automation of perception, for the innovation of artificial vision, delegating the analysis of objective reality to a machine, it might be appropriate to have another look at the nature of the virtual image … Today it is impossible to talk about the development of the audiovisual … without pointing to the new industrialization of vision, to the growth of a veritable market in synthetic perception and all the ethical questions, this entails … Don’t forget that the whole idea behind the Perceptron would be to encourage the emergence of fifth-generation “expert systems,” in other words an artificial intelligence that could be further enriched only by acquiring organs of perception.[9]

Optical accelerationism has very little to do with the visible but, rather, with the imperceptible; cinematic and other forms of visible motion — apparent acceleration and projective geometry — can be translated into mechanical problems. This example illustrates what continental philosophy can learn from analytic philosophy and what post-continental philosophers are already attempting to achieve.

Let us think back to Archimedes of Syracuse who dissolved the distinctions between science and technology—Pasquinelli’s reinscription of ethnomathematics to Mesopotamia reeks of bewildering theoretical naivete. Machineology—that is, machines as an entity which is constantly traversing between the abstract and concrete—would be nothing without Archimedes’ footing; his machines are completely Janus-faced, paving the trajectory of pluralized systems, including lens-making, electron-interference, and Galilean and Einsteinian systems. Similarly, the computational paradigm (including the Church-Turing thesis) is always plastic—machineology and the history of technology show us the trivial nature of the separation between concrete and substantial data, upon which the author’s history of the algorithm is imposed.

NOTES

[1]Matteo Pasquinelli “Three Thousand Years of Algorithmic Rituals: The Emergence of AI from the Computation of Space” e-flux Journal #101 — summer 2019.

[2]Frank Rosenblatt, “The Perceptron: A Perceiving and Recognizing Automaton,” Technical Report 85-460-1, Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, 1957.

[3]Matteo Pasquinelli, ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] Philia, generally translated as friendship or ethics, is that which, according to Aristotle, contains madness. Stiegler remarks that “friendship is a fundamental vector … which the philia characteristic of an epoch is formed,” holding together the members of a community; philia is also “what is torn apart when a civilization degenerates”; see Bernard Stiegler, The Age of Disruption: Technology and Madness in Computational Capitalism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2019), 20/53.

[6] Contemporary cyberneticians usually make a distinction between “first-order cybernetics” (e.g. Walter and Ashby) and “second-order cybernetics” (e.g. Bateson, Beer, and Pask); this distinction is often phrased as the difference between the cybernetics of “observed” and “observing” systems, respectively. “Second-order cybernetics, that is, seeks to recognize that the scientific observer is part of the system to be studied, and this in turn leads to a recognition that the observer is situated and sees the world from a certain perspective, rather than achieving a detached and omniscient ‘view from nowhere.’” See: Andrew Pickering, The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2010), 25.

[7] Predictive processing draws on: 1) Kant’s Copernican shift – that objects conform to us; 2) Helmholtz for the idea of unconscious perceptual inference, or what is sometimes termed “perception as hypothesis testing.” These two ideas are complementary.

[8] Reza Negarestani et al., “One Thousand & One Nights and A Handful of Plateaus,” The New Centre of Research & Practice (June 16, 2019); link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGK2KpBbJjg

[9] Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994. 76.