The Middle East continues to painfully be a primary site for the blood-drenched transformations of our planetary geopolitical system. However, about ten years ago and during another Israeli operation in Gaza, an uncanny timeliness opened an unexpected connection between global contemporary art and geopolitics in August 2014 when, following the escalation of Israel’s Gaza operations, a planned exhibition of works from and about the Arab world opened at New York’s New Museum. Not only was the exhibition the biggest of its kind but, in addition to works from Palestinian artists throughout the show, the fifth floor of the museum housed a separately curated presentation of art and archival materials about and from Palestine.

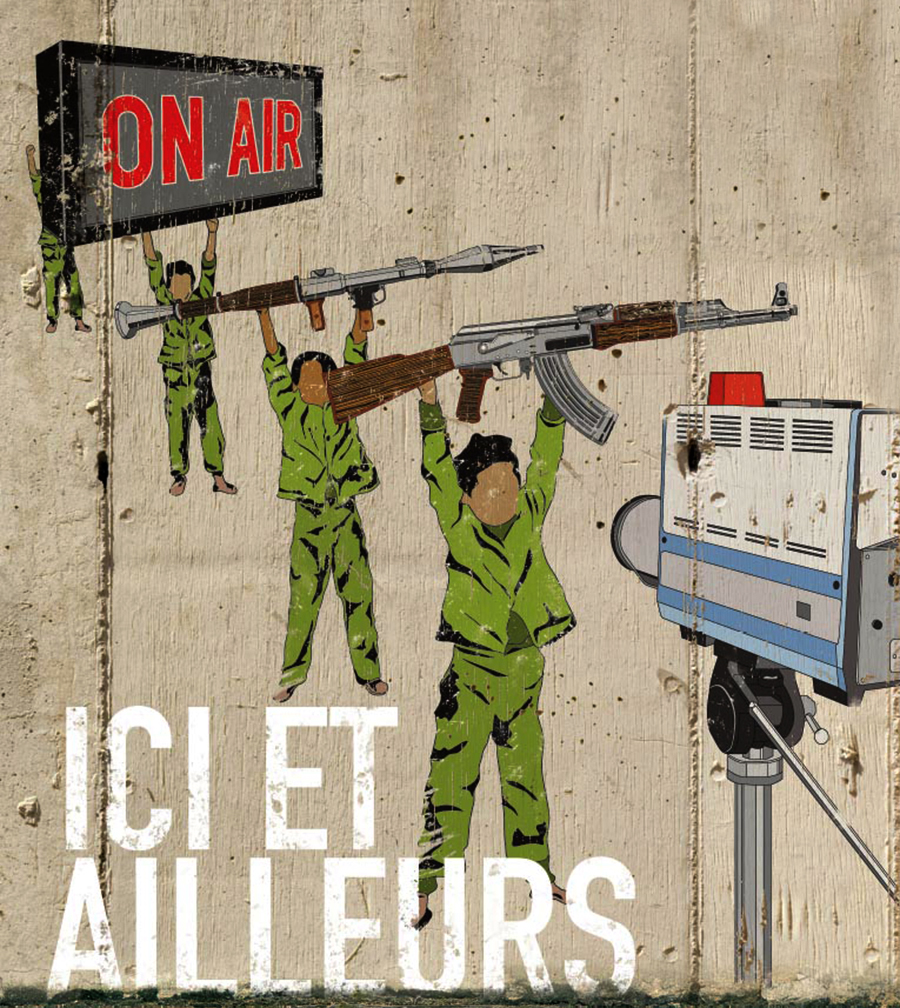

It’s merely a truism to respond to this happenstance with the well-known quote by Walter Benjamin, that “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” However, investigating the subtleties of Benjamin’s link between civilization and barbarism seems especially pertinent to these coincidental exposures of the politics of the Arab world in that the operating logics of both Israel’s Operation Protective Edge and New Museum’s “Here and Elsewhere,” each in their own way, contend with the form and content of the anticolonial resistance that has historically provided the raison d’être for so much of Arab art, specifically contemporary art from Palestine.

This text considers whether the coincidental exposure of geopolitical violence in the Middle East and art from the region to audiences in the global north can help us understand the future of Palestine and the future place of production and distribution of contemporary art. It was written as an introduction for an event co-organized by the author at Manhattan’s Whitebox Art Center on August 5, 2014, featuring other speakers and presenters such as Khaled Jarrar, Ariella Azoulay, Joseph Audeh, Judith Rodenbeck, Alex Shams, and Myriam Vanneschi.

+++

I’m going to open tonight’s talk with two disclaimers about what this event is not, and what it should not be about. First, we are not here to assess Israel’s and Palestine’s war from a local perspective, i.e., who did what, when, and how. Nor are we here to act as a moral metric or an ethical compass for the ongoing war. We are also not here to blame parties or to further sensationalize something that already has been obviously registered as outrageous for a wide spectrum of opinions.

The frame I am deploying tonight is already controversial enough: We are dealing with a New York exhibition of Arab and Palestinian art whose explosive charge could only be activated through a bizarre, coincidental overlapping of cultural and military schedules here and elsewhere.

This can converge upon a third disclaimer: We are not here to perform a classic historical overview of the problem. From a local perspective, we will neither delve into the past of Palestine and its various so-called resistance ideologies nor in the past of Israel and Zionism. We will not generalize using terms like the culture of colonial conquest, a favorite topic of the cultural left, or explore the right-wing obsession with the Islamic cultural sacrifice. We will also not reenact the theater of surprise when dealing with the worldwide complicity in this latest round of barbarism. We will also not pretend we are disappointed by the American or European response to the crisis. We will not pretend to be shocked at the Arab nation-states for their silence and inaction.

Instead, what we are doing has more to do with the emergence of Palestinian contemporary art and its current celebration here in New York than with the ongoing war elsewhere in the Middle East. In fact, I decided to organize tonight’s event after visiting the “Here and Elsewhere” exhibition at the New Museum, which, as our press release reads, uncannily coincides with the escalation of Israel’s ongoing war on Gaza and the West Bank.

After looking at works of art by Palestinian artists in the show and hearing the news of the Israeli authorities’ cancellation of Khaled Jarrar’s planned trip to New York, I thought it would be a good idea to think about the future of art in the context of Palestine. Jarrar is one of the artists in the New Museum show, and he is also with us here tonight. His work is also the focus of a solo exhibition here at the Whitebox Art Center, curated by Miriam Vanneschi.

While organizing this event, I thought how pertinent it will be, in the context of this coincidence, to revisit Benjamin’s famous passage from the “Theses on the Philosophy of History”: thesis number seven, in which he talks about the overlapping of the categories of civilization and barbarism in the very materiality of monuments and documents. This particular thesis I’m quoting has to do with Benjamin’s contrasting of historicism versus historical materialism. Maybe the best thing will be to read a long section of this piece, to better grasp what is at stake at tonight’s discussion:

[. . .] if one asks with whom the adherents of historicism actually empathize[, t]he answer is inevitable: with the victor. And all the rulers are heirs of those conquered before them. Hence empathy with the victor invariably benefits the rulers. Historical materialists know what this means. Whoever has emerged victorious participates to this day in the triumphal procession in which the past rulers step over those who are lying prostrate. According to traditional practice, the spoils are carried along with this procession. They are called cultural treasures, and a historical materialist views them with caution. For without exception the cultural treasures have an origin he cannot contemplate without horror. They owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free from barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another. A historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from it as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history up against the grain.

That is my theoretical frame for tonight’s discussion. I’m arguing that understanding the art-war nexus in the twenty-first century requires a new form of historical materialism—one that, in addition to the careful consideration of the relevance of the past to the present, is also aware of the future’s traction on the unfolding of the contemporary moment; a historical materialism whose new angel is not a painting and perhaps is another kind of a machine, not just obsessed with the ruins of the past, but those of today and tomorrow—I was thinking about Khaled Jarrar’s piece in the show as a kind of machinic remembrance of the dead; the work is a fitting replacement for Benjamin’s Angelus Novus: When entering the room you hear a voice, cold-bloodedly reading the name of those who have been killed in Gaza—a historical materialism that, once and for all, recognizes the history of the conflict in a search amid the past and present in order to find a future.

There is also a more contemporary and strictly art-historical frame for tonight’s discussion, which has the entanglement of culture and the geopolitics of the Cold War at its crosshair. An example that if read against this new philosophy of history I’m proposing tonight, actually should and could have indicated how all global art after the Cold War would always be closely entangled with geopolitics. I’m referring to the now classic volume by Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole The Idea of Modern Art.2 In this volume, he recounts the story of the American state and capital’s role in the ascendance of both New York and Abstract Expressionism to the cultural center of the West right after World War II.

This book is obviously a document about the political essence of art, but perhaps also a case study for a more radical proposition that I would like to make: All art, due to the social nature of its production and distribution, should be considered as politics par excellence. The future use of this historical study then allows us to wade through what is presented by the New Museum, not in terms of the organizers’ various claims about the introduction of new forms and aesthetics to the global art dialogue, but in regard to the political economy of global art from the Middle East—reflected in the exhibition funding by privately owned Middle Eastern postal services, as well as the super wealthy patrons who own global waste management companies, multinational high fashion retail chains and luxury airlines.

But it is not really sufficient to foreclose on the New Museum’s exhibition solely based on its financial support structure. The problem we face goes far beyond the familiar theme of art as a financial instrument and the use of museum exhibitions for helping to guarantee our crisis and careers in the future for artists. If that was the case, a follow-up to Serge’s book would be titled How Bloody Petrodollars Shape the Structures of Contemporary Art: Here and Elsewhere. So, let’s return to the show itself.

The New Museum’s polite and neutral presentation of materials—meaning the artworks and the archives from the Arab world—form the body of the exhibit. I’d like to suggest that the anti-colonial resistance from the region in the past and the Palestinian resistance in the present provide the show with its quiet but haunting specter or soul. Quiet, because you will only notice this living soul if you read the wall text or study the exhibition’s accompanying text.

There could be an exception about this point: an intervention in the catalog, which has been printed purposefully on yellow-colored paper. This departure from the museum’s bland narrative provides readers the closest thing to a rigorous understanding of art production and circulation from the Middle East. Yet even this intervention fails, as it cannot go beyond its own readymade critique of the political economy of art and images, and does not dare to directly address geopolitics from the position of art.

It does not engage in the challenge of distinguishing the anti-colonial from the post-colonial using the objective metrics of decolonization. It is very rare, if at all possible, to find in the show or the catalog an attempt to dislocate the Arab question from its multiple disjointed localities and simultaneously unite and connect them with what has been going on on a planetary scale from a temporal perspective. The show provides us with plenty of local details about the past and sometimes the present, only to inform us about particular ideas, moments, or events overall.

Besides a few exceptions, the show—not as a collection of individual great works, but itself as a unified entity—fails to transcend the limitations of contemporary art, as set by thinkers such as Suhail Malik and his identification of contemporary art indeterminacy, Peter Osborne’s rebuttal of contemporary art’s claim to contemporaneity, or Sinéad Murphy’s problematization of art’s obsession with its own evolving but self-declared definitions.

In light of the current conflict, and even if supplied from a region experiencing decades of conventional and civil wars, guerrilla urban warfare, and recently, revolutions, contemporary art still fails to sufficiently account for the politics proper or how art can potentially be reconfigured to anticipate and make a future. For the existing Western left, the future has already been cancelled, and the end of history has forever ruined the possibility of a break out of the short loop that is the neoliberal present.

Securing the future means opening up spaces through taking and managing risks, moving faster, and ushering in new epochs through synthesizing detailed plans with unknown contingencies as a means of getting traction on a desired future. This is what we desperately are in need of. This is why perhaps the twenty-first century, as we live it today, quite abruptly began with the surprising conquest of the rest of Palestine by the Israeli army by the end of the Six-Day War on June 10th of 1967, in a year that philosopher Elizabeth Susan Kassab has already referred to in the exhibition catalog3 as a turning point in the history of the region—an event which meant so many things at the same time, among which we can count the beginning of the end of Arab secular nationalism as the dominant anti-colonial force in the region, and the slow but steady rise of political Islam as its so-called alternative.

The 1967 war was also the basis for Khomeini’s famous lectures in Iraq in 1969, providing a blueprint for the clergy’s governance in Iran after the revolution. According to this reactionary, future philosopher-king of Iran,

[i]f the rulers of the Muslim countries truly represented the believers and enacted God’s ordinance, they would set aside their differences, abandon their subservience and divisive activities and join together like the fingers of one hand, then a handful of Jews, the agents of America, Britain, and other foreign powers, would have never been able to accomplish what they have. No matter how much support they enjoyed from America and Britain.4

The 1967 war also meant the expulsion of Palestinian Liberation Organization from the West Bank and Gaza and the migration of refugees into neighboring countries. Its short and long-term devastating effects were the Black September massacre in Jordan, implemented by the future dictator of Pakistan—who later on played a crucial role in coordinating the Saudi US-backed project of the weaponization of Islam through arming and supporting the Afghan Mujahideen against the Soviets, and also the civil war in Lebanon that brought us the first twenty-first century proxy war in the Middle East, combined with car bombs and other urban warfare techniques and tactics.

These events were followed by other regional conflicts and wars, each more brutal and barbaric as well as innovative and effective in their aims than the one before it, namely the Iran-Iraq War, the Gulf War, the Yugoslavia civil war, as well as the Chechen war. Together, these caused the awakening of Russian nationalism in the KGB and the KGB’s response to the NATO threat with Putin. These conflicts were all fought along the lines originating in the Cold War, but slowly spiraled out of control into the future chaos we now call the twenty-first century.

So we are here now: Israel is supported by the global liberal North, but also by Arab monarchies of Saudi and UAE, who have also been very enthusiastic in investing in and promoting contemporary art from the region. On the other side, we have Turkey and Qatar, two other contemporary art loving nation states who are, from one side, friends and allies of the global neoliberal north, and from the other, the go-between, if not allies of Taliban, Muslim Brotherhood, and Hamas. They have been in competition with the Saudi Axis for regional influence, but this does not stop them from working hand in hand with Qatar and Turkey against the Shia in Iraq and Iran, funding and supporting ISIL, which now is in charge of half of Iraq.

Let’s go further: We now have neo-Nazis in Europe who support Israel. Among them, Marine Le Pen, the president of the French National Front, and other even more extreme figures who identify Israel with wealth and power, and see Muslims in Europe as a common enemy. So the question can‘t really be whether we should or should not focus on the Israel-Palestine conflict, but how to place this very old local problem that links the twentieth century’s Cold War geopolitics to today’s flurry of new planetary developments.

In a short piece commissioned for Le Monde in 1978, Deleuze expresses his fears about the future of the world by stating: “Today Israel is conducting an experiment. It has invented a model of repression that, once adapted, will profit other countries.”5 Does this allow us to ask if Israel’s method of suppressing Palestinians is still a worrying model of the future of the world?

I will now quote from a lesser-known work by an almost forgotten political thinker, Guy Debord, and his “Comments On Society of the Spectacle”—a statement about liberal democratic governments that, for better or for worse, still resonates strongly in the geopolitical manifest image of the twenty.first century. I am talking here about terror and terrorism, which was introduced to Western culture in the second half of the twentieth century by Israeli political discourse. As predicted by Deleuze in 1978, it was generalized, if not also globalized, by the neoliberal North after the September 11 attacks. These days, even enemies of America, namely Iran and Russia, have conveniently adopted this category to define their ultimate enemies. Debord writes:

Such a perfect democracy constructs its own inconceivable foe, terrorism. Its wish is to be judged by its enemies rather than by its results. The story of terrorism is written by the state and it is therefore highly instructive. The spectators must certainly never know everything about terrorism, but they must always know enough to convince them that, compared with terrorism, everything else must be acceptable, or in any case more rational and democratic.6

As to the spectrum: The known contemporary philosopher of science Bruno Latour—a Catholic, and quite to the right of liberal—quite perversely defines the Eurocentric unfolding of both the twenty-first century and the bloody process of globalization as that of the competition by the West with the rest, for remaining relevant. He writes:

After having registered the sudden new weakness of the former West and trying to imagine how it could survive a bit longer in the future to maintain its place in the sun, we have to establish connections with the others that cannot possibly be held in the nature/society collectors. Or, to use another ambiguous term, we just might have to engage in cosmopolitics.7

My question is: Could it be possible that fighting the Other as terrorists (think about Fallujah and Syria before we even think about Gaza) by destroying their cities while celebrating the culture in our own cities, is the very precise practice of Latourian cosmopolitics?

And to revisit Benjamin’s passage at the end: Is cosmopolitics a mixing of civilization and barbarism with an empathy with the victim, not just with the culture of the victor?

My final point will be precisely about the temporal feature of the seemingly unrelated but nevertheless simultaneous operation at the Museum and at the war front. If in the past, a delay separated the exercise of barbarism from the celebration of the spoils of the war as treasures. As an example, think of how long it took Europe to actually begin to take up the Holocaust culturally. If up until now the conqueror had to wait for the annihilation of the enemies in order to consider them as civilized people capable of producing art and culture, in today’s complex and networked world the delay is removed; the killing and celebration can finally and simultaneously take place.