It is after the end of the world. Don’t you know that yet

San Ra’s “It’s after the end of the world” is apparently especially suitable for a gloomy Moscow morning. The repeated screams of Sun Ra “It’s after the end of the world. Don’t you know that yet?” resonates with the low grey sky’s haunting sense of absence of future, beyond the endless cycle of reproduction of the same, as it was described by Mark Fisher, “neoliberalism[‘s] static catastrophe”[i]. By the time I woke up the sun had already set (not sure whether it even had been up).

The general fogginess of the day reminds me how I first came across Mark Fisher’s words on the state “after the end of the world”. His essay was in a book titled Catastrophe, which I bought while trying to get over a painful break up a couple of years ago. Even at that time, the concept of the world “ending” big bang didn’t feel relevant, rather it was this feeling of being stuck in some sort of slump: not being able to feel or move, but still being able to see and breathe. I burn my tongue with coffee, it wakes me up from falling down a romance memory hole. I realize that I came across something quite similar in a different context—Madina Tlostanova describes the relatively recent neo-reactional turn in Russian politics as a process of cancellation of the future: “we are offered to be happy with the symbolic victory over the imagined enemies, and practice spiritual and religious superiority and aggressive Messianic zeal, uncompensated with anything in this material world.”[ii]

The world has already ended in all different ways. However, this doesn’t mean that there is no place for utopian thinking and a search for alternative futures, on the contrary: the search for alternative futures is what the whole situation calls for. I relisten, “It is after the end of the world” album from the very beginning, it starts with repeating high-pitched “Dreamworld, strange world, a world, a world”. I get lost in the sound for a while, trying to follow the process of sonic worlding, at some point “it’s after the end of the world” screams are rather filled with hope for an alternative future, then with desperation. However, unlike Sun Ra’s dreams and hopes for alternative futures somewhere out there (“We travel space ways”), I feel that Earth is the only available space to build different futures.

How can alternative futures be facilitated?

My understanding of the ways to construct alternative futures is deeply informed by the Xenofeminist manifesto, which famously claimed “feminism is rationalism”[iii], calling for the reclaiming of rationality for the construction of unnatural freedom. However, what was absent from the manifesto is the way rationality could be put to use. I propose seeing rationality as an infrastructure which could facilitate an alternative future. Writings on infrastructure propose some useful insights into the way rationality is materialized in collectively built environments. The researcher of infrastructure, Paul N. Edwards, describes the relations between it and modernity “Building infrastructures has been constitutive of modern condition, in almost every conceivable sense. At the same time ideologies and discourses of modernism have helped define the purposes, goals and characteristics of those infrastructures”[iv]. Similarly Adolf Gruhnbaum, in the essay “Free Will and the Laws of Human Behavior”, discussed that the rationality behind a prison system actually facilitates the reproduction of crime as it supports the existing hierarchies and doesn’t allow people to move inside them[v]. Rationality has been extensively criticized as part of the project of modernity. However, like infrastructure, it can both facilitate the movements of Empire as well as the resistance as it is discussed by feminist researcher of logistics Deborah Cowen, who defines infrastructure as “collectively constructed systems, which build and sustain human life”[vi]. She also mentions that a focus on infrastructure “needs the insights of feminist thought on the centrality of social reproduction and its gendered and racialized labors to the reproduction or transformation of the social order”[vii]. In a later conversation with Niccolo Cuppini[viii] she further elaborates on examples in military logistics, explaining that no armies move without someone cleaning and washing clothes for them. Thus future battles are conditioned by those who put the clothes in washing machines and operate vacuum cleaners. Those systems of infrastructural labour are never constructed by one person, it always involves work of several people.

However, so far Deborah Cowen has mainly discussed the relationship between infrastructure and social reproduction only in relation to military operations. Although the border between military and civilian operations is quite porous, I will discuss the civilian creation of infrastructure through Irina Aristarkhova’s concept of “hospitality”. Aristarkhova starts by criticizing the way concrete and often gendered actions such as cooking meals and cleaning are overlooked when it comes to discussing hospitality in philosophy. She points out: “Acts of hospitality are unaccounted for, or even denied existence, since it is difficult to imagine how this nonempirical ‘dimension of femininity’ can cook, clean, and make a bed”[ix]. Her emphasis on concrete actions of hospitality mirrors the way Deborah Cowen discusses the way military infrastructures of social reproduction facilitate future battles. As in Cowen’s understanding of the entanglement of infrastructures and social reproduction, Aristarkhova conceptualizes gestation as hospitality by empathizing the labor that includes the creation of a nourishing environment for a fetus both in the cases of “natural” and “artificial” gestation. She also points out that neither is an endeavor of solitude nor solely a human practice. Both include the labor of nurses, in some cases doulas and, in other, so-called “wet-nurses” alongside a variety of human-technology alliances.

I have emphasized the material aspect of reasoning, but I have left out a discursive one. The Soviet Psychologist Lev Vygotsky’s approach to cognition focuses on the way a material environment, as well as discursive surrounding (community), influence a child’s upbringing[x]. Thus, according to him a child’s orientation in a world is constructed through various forms of games and activities and not through “teaching” them anything.

I understand the process of reasoning as a process of construction of an infrastructure, which, although done by humans, also includes alliances that only partly involve humans. Any process of reasoning imagines a certain model of a future. Although such futures are conditioned by material systems, they are also conditioned by the human interactions that make those systems possible.

To further discuss my approach to the material constructions which can facilitate alternative futures, I will look at Soviet Kinetic art. I will not be discussing its position in the system of the Soviet Art in the 1960s when it first originated. Rather, I will perform a temporal loop and look at the rationalities and futures these rationalities facilitated.

Dvizhenie

The Dvizhenie (from Russian: movement) group was one of the key groups of Russian Kynetism. It was organized in 1962 by approximately 60 young artists, who studied in MARKHI (Moscow Architectural institute). They performed a temporal loop themselves by referring to the practices of the avant garde artists of the Soviet 1920s, which at the time of the group’s formation weren’t widely discussed or even visible. Art historian Alexandra Novozhenova discussed the difference between the 1920s experiments and the ones from the 1960s, differentiating their approaches to abstraction (i.e., comparing the constructions of avant-garde artist Karl Ioganson to those of the Dvizhenie group). According to her, Ioganson’s Tensegrity were the “culminations of his research of the abstract form before he switched to organizational work… his objects literally support themselves and their construction is the fundamental reason for their existence”[xi], while the objects of Dvizhenie group “represent the ideas of scientific progress”. However, authors writing about Kinetic art rarely discussed what they meant by the idea of “scientific progress” that was represented by the Kinetic artists.

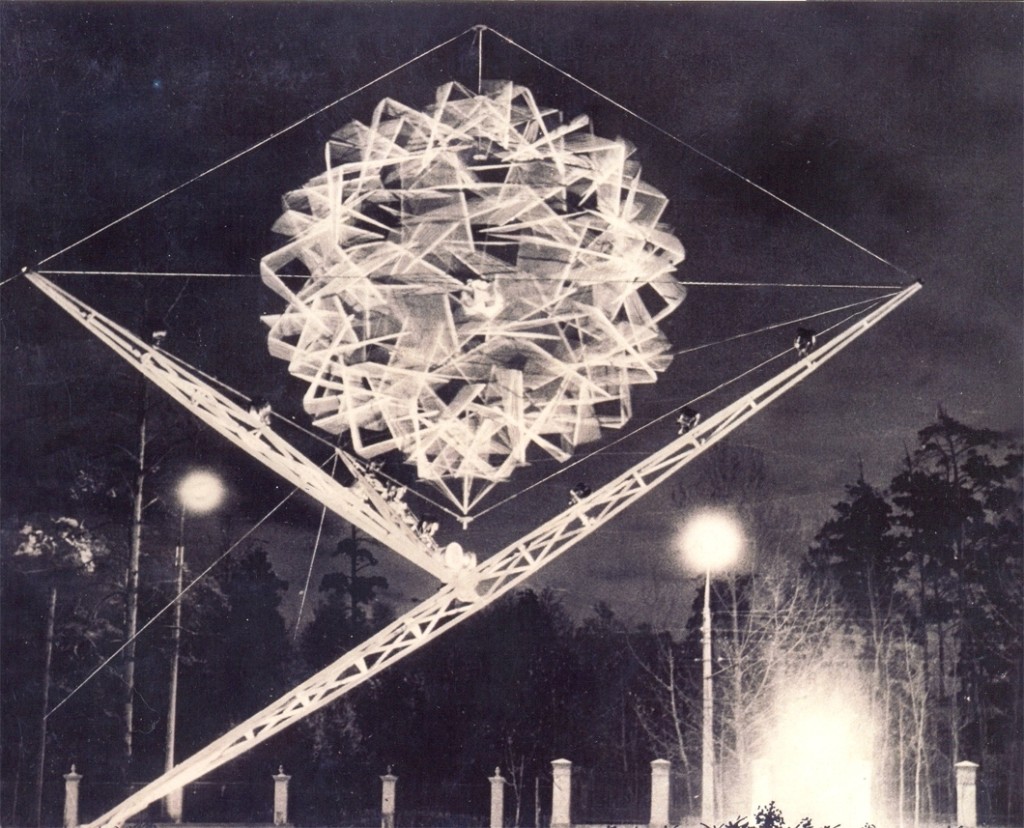

Viacheslav Koleichuk and Mir group, Atom.1967, kinetic installation, Kurchatov Square, Moscow Photo Viacheslav Koleichuk Archive.

Viacheslav Koleichuk and Mir group, Atom.1967, kinetic installation, Kurchatov Square, Moscow Photo Viacheslav Koleichuk Archive.

Novozhenova discusses the artwork “The birth of an Atom”(1967) by one of the members of “Dvizhenie” Vyacheslav Koleychuk and the “Mir” group as an emblematic piece for Kinetics’ approach to abstraction. The artwork was a monument in front of the Kurchatov Institute for Atomic energy. It was supposed to represent the idea of a “peaceful atom”, which was emblematic to the soviet modernity. Rationality, which informed this modernity, is discussed by Anibal Quijano. He describes the naturalised understanding of the state as a hierarchical organism, inside of which some citizens are “hands” while others are the “brain”, with the prerogative of the “brain” to teach the “hands” enacted both by the Soviet government as well as other European forms of colonialism. Any other ways of making sense that didn’t fit into the subject-object models of rationality has been considered «barbarian» by both European colonialism[xii] and the Soviet model. This understanding of rationality has been repeated in the way indigenous communities have been treated by both Russian and the Soviet governments. The politics of “Russification” has led to the extinction from the territory of Russia any languages aside from Russian, as they are not considered worthy of being “saved”. Thus the indigenous communities act as figures of “Caliban” as they talk “nonsense” and are therefore not considered worthy of care. Thus it might seem that Koleychuk’s work facilitated the futures of the soviet modernity, which cancelled any other futures, including the ones of indigenous people, by annihilation of them. I will now move on to critiquing the way the rationality of “scientific progress” was materialized in the artwork by Vyacheslav Koleychuk in order to describe the creation of a dynamic space that asked for reason to emerge, as other artworks of other Kynetic artists.

The model of an atom, constructed by Koleychuk, is represented not as a stable entity, conceivable for the human cognition, but as a dynamic field, moving in several directions. Other works and ideas of members of Dvizhenie group functioned in a similar manner. For example, art historian Ekaterina Andreeva quotes a phrase from a letter of Lev Nussberg (a group founder):

I want to work with electro-magnetic fields, with pulsing plasma clots in space, with movements of fumes and liquids, with mirror and other optical effects, with the changes of temperatures, with various smells, and of course, with music.[xii]

Nussberg enumerates that he wants to work with mostly dynamic entities which call for the conception of occupation via a dynamic perspective.

The Mirror installations (1970-1980s) of Francisco Infante-Arana and Nona Goryunova similarly created a destabilized space. In his works, objects made of mirrors are situated in forests and fields. This intervention in the landscape positions a human eye under the mirrors, the process of interaction between the elements of a landscape and a mirror happens outside of human control; as a human doesn’t see herself in these mirrors, she becomes a blind spot in this interaction. The space was neither completely “natural pastoral landscape” nor a completely constructed “artificial” one. Thus it traversed possible preconceptions of what can be “nature” thus creating a sense of disorientation for a human gaze. Rather than imposing any sort of rationality, this artwork created a disorienting space, from which reasoning could evolve.

![Lev Nussberg. Plan of a kynetick playground. 1968. Image source Andreeva Ekaterina, [Corner of discrepancy] (In Russian).Iskusstvo, XXI-vek. 2012. 55](https://tripleampersand.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Lev-Nussberg.-Plan-of-a-kynetick-playground.-1968.-Image-source-Andreeva-Ekaterina-Corner-of-discrepancy-In-Russian.Iskusstvo-XXI-vek.-2012.-55-1024x657.jpeg)

Lev Nussberg. Plan of a kynetick playground. 1968. Image source Andreeva Ekaterina, [Corner of discrepancy] (In Russian).Iskusstvo, XXI-vek. 2012. 55

Similar process was represented in Nussberg’s “Plan of kinetic children’s playground” (1969). It consisted of colourful forms, which did not resemble any everyday objects, they rather looked like something, which had been stopped in the process of moving in different directions. It could be speculated that Nussberg’s aim was to create a nourishing environment for children to play in. Although those forms didn’t resemble anything familiar, they were not abstract; rather their constellation was a representation of ideas about the way social reproduction could function. According to Nussberg, it could function as an unending process, one that continues whirling about in various directions.

The accent on a process did not create any linear futurity; however, it emphasized a space for reasoning to emerge. This did not create one single and pre-conditioned model of futurity, but it intensified the sense of being lost and disoriented.

However, a sense of disorientation is not a neutral condition and has been seen as defining for those who have been affected by colonial violence. For example Eduard Glissant used the concept of the “abyss”[xiv], which he describes as the experience of the unknown, the result of being subjected to violence. Although he discussed the state of being in the “abyss” as the only possible universal condition, he used the experience of slavery as a starting point to discuss it. Although the experience of postcolonial disorientation was not reflected upon by Kynetic artists, it could be a recognisable condition in, for instance, indigenous people displaced by the Soviet colonization. Thus, without the artists’ intention, some of the Kynetic artists’ works reproduce the state of postcolonial disorientation, which makes demands of the labour required for reasoning (despite simultaneously evoking a sense of loss). This positioning of a viewer emphasizes the material dimension of reasoning and the imagining of an alternative future, since it is the disorienting environment that makes her dizzy.

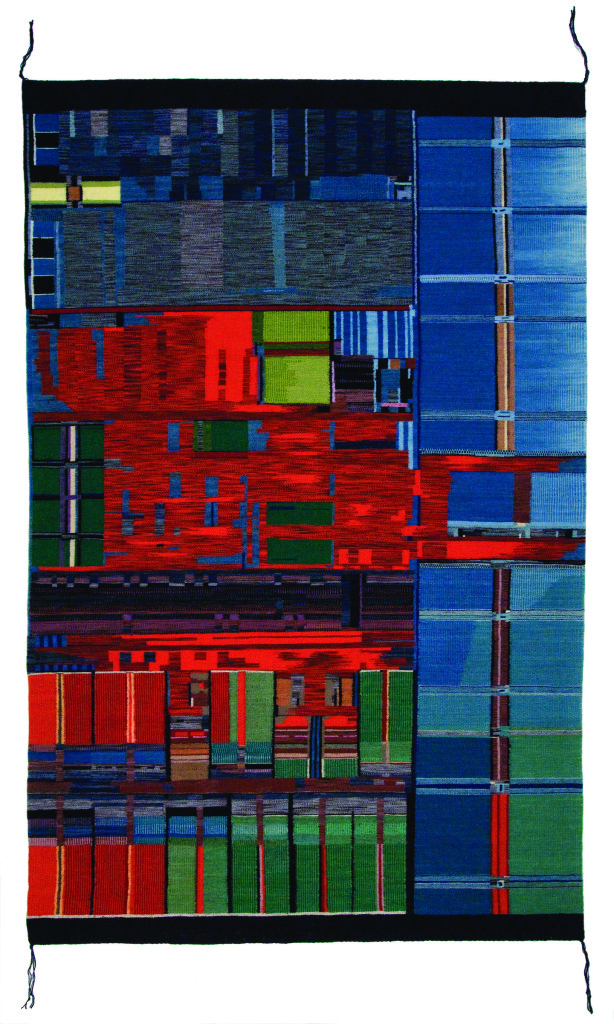

Marilou Shultz. Untitled (2008) Wool. Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City.

Labor behind futures

Creating space for reasoning does not seem like a sufficient practice, although it does make the labour of reasoning more tangible. The pattern of the weaving (2008) by Marilou Shultz might seem like an “abstraction” at a first glance, however, like Koleychuk’s atom it has very specific figurative meaning. It refers to a pattern of a microchip, which sends the viewers on another temporal loop. They now find themselves at the United States of America in the 1970—more precisely in a plant (Fairchild Shiprock). They see a long row of women, looking at microscopes and assembling something under them. Specifically, Navajo women produce these microchips, which would be used as material infrastructure for the Silicon Valley visions of the future filled with cyborgs and total digitalization. In her research on the production of microchips by racialized and gendered workers, who often face great difficulty in unionizing and whose labour is not well compensated, Lisa Nakamura pointed out that:

The affinity and historical links among weaving, digital computing, and women figures centrally throughout cyberfeminist theory, most famously ‘A Cyborg Manifesto.’ Silicon Valley business discourse created an archive of materials that represented Navajo women as “natural” cyborgs, indeed, as embodying nature itself using silicon as their medium.[xv]

Thus emerges the seemingly non-human reasoning of computers that is conditioned by the labour of racialized and gendered bodies represented as only “partly human.” As Franco “Bifo” Berardi describes these visions of the future:

The process of decision-making and projecting a future in which one future among many is selected depends less and less on human will. We may call it the paradox of the decider: as the circulation of information becomes faster and more complex, the time available for the elaboration of the relevant information becomes shorter. <….> This is why the execution of the program is entrusted to automated procedures that human operators cannot change nor ignore[xvi]

Bifo’s description implies that the techno-futures were produced by non-human reasoning; however, the temporal leap of Marilou Shultz’s work produces a different history of techno-utopia. It shows the materiality of gendered and racialized bodies conditioned those futures. The process of reasoning does belong to machines, but to the tired hands of those who produce them. [xvii]

Conclusion

Print-screen from video «How a motherboard is made Inside the Gigabyte factory in Taiwan». PC World.2018

The last time I had a migraine, I spent the whole day sleeping as I couldn’t stand up without immediately fainting from a headache. While headache-hallucinating/dreaming, I saw that my laptop dissolved into its elements: motherboard, hard-drive, keyboard letters, cooling system, screen: they all started to separately levitate over the table. Each element became a portal, prepared to send me to the process of its production. I got inside a motherboard and soon saw, walking along a conveyor belt, that I was destined to observe the process from the perspective of an assembled object. I thus saw not hands, but a line of mostly female and mostly brown faces assembling me. Suddenly a weird glitch inside a dream happened. I turned into a completely different substance. I was not exactly sure what I was at that time: but I had a nice smell, indicating that I was most probably tasty and made of noodles, meat, and vegetables. Yet I saw the very same face leaning over myself, I could also faintly recall when I was a motherboard.[xviii]

NOTES

[i] Mark Fisher. After the event in Catastrophe. Michael Corris et al. Eds. London: Artwords Press. 2012. 35- 43

[ii] Tlostanova, Madina. What Does It Mean to Be Post-Soviet?: Decolonial Art from the Ruins of the Soviet Empire, Duke University Press: Durham and London. 2018. 21

[iii] Cuboniks, Laboria. “Laboria Cuboniks | Xenofeminism.” Accessed January, 13. 2020. https://www.laboriacuboniks.net/.

[iv] Paul N. Edwards. Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, time and social organisations in the history of sociotechnical systems in Misa, Thomas J., Philip Brey, and Andrew Feenberg eds.

Modernity and Technology. Cambridge: MIT Press. 2014. 185 – 225

[v] Adolf Grunbaum “Free Will and the Laws of Human Behavior” in Collected

Works, Volume I, Scientific Rationality, the Human Condition, and 20th Century

Cosmologies. pp. 79-95.

[vi] Deborah Cowen. “Infrastructures of Empire and Resistance.” Versobooks.com. Accessed January, 14, 2020. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3067-infrastructures-of-empire-and-resistance.

[vii] Ibid

[viii] Cuppini, Niccolò. “Circulating Violence and Value.” Social Text 37, no. 4 (December 1, 2019): 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7794414.

[ix] Irina Aristarkhova,Hospitality of the Matrix Philosophy, Biomedicine, and Culture. New York: Columbia UP, 2012

[x] Lev Vygotsky. [Basics of defectology] (In Russian) //bookap.info/clasik/defect/gl2.shtm Accesed February, 20. 2020

[xi] Alexandra Novozhenova, Gleb Napreenko. [Episodes of modernism. From the roots to crisis] (In Russian). NLO. Moscow. 2018. 150

[xii] Aníbal Quijano, “COLONIALITY AND MODERNITY/RATIONALITY,” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (March 2007): 168–78, https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353.

[xiii] Andreeva Ekaterina, [Corner of discrepancy] (In Russian).Iskusstvo, XXI-vek. 2012. 157

[xiv] Glissant, Édouard, and Betsy Wing. Poetics of Relation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. 33

[xv] Nakamura, Lisa. “Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture.” American Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2014): 919–41. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2014.0070. 934

[xvi] Berardi, Franco, Gary Genosko, Nicholas Thoburn, and Arianna Bove. After the Future. Edinburgh: AK, 2011. 44

[xvii] Valentin Golev recently made a similar point, concerning the relationship between labour and the AI. His point was quite inspiring to my own thinking about the issue of reasoning and its relation to materiality. In the comments to his post Brent Lin recommended Lisa Nakamura’s article, which was crucial to my thinking. Valentin Golev’s facebook page. Accessed February, 22 https://www.facebook.com/valentin/posts/10219738897639197

[xviii] As Ursula Le Guin pointed out in her “A rant about “technology””: it is through technology that society copes with physical reality; how people get and keep and cook food, how they clothe themselves, what their power sources are (animal? human? water? wind? electricity? other?); what they build with and what they build, their medicine and so on. See further. Ursula Le Guin. A Rant about technology. http://www.ursulakleguinarchive.com/Note-Technology.html Acessed March, 11. 2020