The Game Begins

To even breathe the words “insurrection versus extinction” is to transport us into a malevolent game, one that threatens us by being based on a single concept: the ultimatum. The very question itself, staged as a fatalistic either/or, assumes a significant breach in the continuum of things, and so we immediately must ask ourselves whether this breaking-point represents a threshold (transitional arch, portal), a precipice (tightrope, cliff’s edge into certain death), or a crossroads (forked path, impasse), since all readings entail different methodologies and possess their own dramatic implications. Beneath whatever veil, though, the catastrophic imagination always places us in the experiential domain of a decision-toward-loss, and so it might be worth considering those strangest games where one is bound to lose or even wants to lose.

We were once warned by a philosopher to “beware the other’s dream, because if you’re caught in the other’s dream you’re done for”, and perhaps we should also extend this logic to waking in another’s game.[1] What we call existence: Are we playing for it, with it, or against it? It seems that two camps have developed in modern thought: on the one side, there are those “being-in-the-world” advocates who treat this sphere as a dwelling; and then you have the more resigned “world-without-us” configuration, who speak of the sheer indifference of the universe. Still, few seem to consider the more aggressive possibility of our “being-against-the-world”, for what if the more fascinating implication is to contemplate an existence that is out to get us, and thus compelling us to react to it adversarially as cutthroat or nemesis? For our purposes, however, it does not matter if the host itself cares nothing for whether we persevere or fade away, or whether it might indeed hold a deep vendetta to ensure our ruin. We must proceed according to the latter alone, for purely tactical reasons.

In those rare instances when insurrection and extinction become simultaneously viable hands at the card-table, we notice a series of emergent incidents: 1) the rise of vanguardism (undergrounds, secret societies, avant-garde circles), where the creative instinct attempts an immense overthrow of the world through cryptic channels and unforeseen turns. 2) the rise of fanaticism (cults, sectarian factions), where the onset of epochal futility and general depletion of purpose is energetically countered by ravenous paradigms of extremity: so it is that nihilistic voids are filled by new militancies, and doomsday visions often thrive in times of famine, conquest, or plague.; 3) the rise of abstraction, where certain rogue individuals place their bets on untimeliness, distance, solitude, and delirium in the face of disaster: these ones restore the storyteller to their rightful function (never to provide distraction, but to be a harbinger of disappearance by literally speaking “the end”); these ones also restore the philosopher to their rightful function (never to provide meaning, but to inspire the will to madness by compounding perplexity).

All roads bring us back to that most treacherous concept of “play” in this discourse of insurrection versus extinction. Many decades ago, Roger Caillois wrote a brilliant treatise titled Man, Play, and Games (1961) in which he delineated 4 fundamental types of games: 1) Agon (games of skill—chess, archery); 2) Alea (games of chance—lotteries, roulette wheels); 3) Mimesis (games of role-playing—childlike pretending, masquerades, costume-parties, video games); 4) Ilinx (meaning “whirlpool” or “vertigo”—games of sensation—skydiving, rollercoasters, virtual reality, childlike spinning until falling dizzy).[2] Beyond these four categories, however, we can add a fifth typology based on games of Subversion (demolishing structures—falling dominos, vandalism, hacker culture) and a sixth typology of Masochistic Defeat (i.e. where the greatest affective pleasure resides in losing or being caught—haunted houses, tag, the knife-game). Nevertheless, do not all of these intricate classifications necessarily assume a human-centric definition of the game, and a sentient or teleological projection of the opponent, thus foreclosing the possibility of our being stranded in the waves of an impersonal and inhuman force? Not in the least, for whether there is actually thought, desire, intention, or volition behind the event, we are still entitled and well-served to perceive ourselves in something else’s crucible: for the desert has its own exclusive modes of passage that one must learn adaptively to survive, as does the forest, the mountain, the jungle, the island, and the sea (each sets its constraints mercilessly). Medieval Iranian poets simply called this concept “the wheel” (what turns of its own drifting accord).

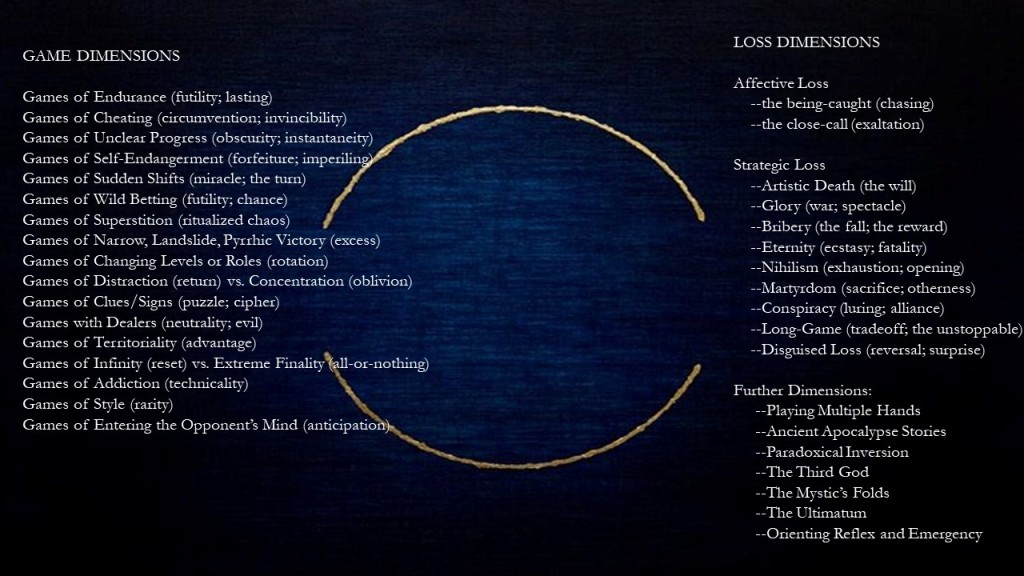

In recollecting the original question of insurrection or extinction, we are therefore compelled to consider the seemingly countless aspects and detailed realms of play, and to re-fathom the aforementioned concepts through such acute prisms one after another:

—Games of Endurance (where the game’s objective is simply to hold out for as long as one can before eventual defeat; a trial of withstanding surrender). Notice how we even marvel at those of exceptional old age as if lasting were an accomplishment in itself: to simply hang on for prolonged stretches of time.[3]

—Games of Cheating (where one can circumvent rules or skip stages). Notice how most people unconsciously conceptualize death in this manner, comforted by delusions of invincibility: that deep down everyone thinks they will be the only one to live forever, thereby foiling death by some stroke of accidental exemption.[4]

—Games of Unclear Progress (where it is concealed whether one is winning or losing until it is too late and the result officially revealed). Lotteries follow this criterion of instantaneous announcement.[5]

—Games of Self-Endangerment (where one willingly forfeits pawns along the way or sometimes moves in the direction of peril).[6]

—Games of Sudden Shifts (where one is losing the whole time until a miraculous comeback in the last phase (jackpot); or vice-versa, where one lets everything ride and falls victim in a single flick of the wrist to the depletion of an amassed fortune (snake eyes).[7]

—Games of Wild Betting (where one forsakes calculation and submits to the futility of programmatic approaches). Thereafter, all movements are determined by negligence, in the hopes that the old Spanish swordfighter’s saying proves true: that the most dangerous opponent for a master is a total amateur, since someone with minimal training will follow the proper forms and be easily undone by the master’s superior technique, but there is always an unpredictable particle in the know-nothing who resorts to wild swinging.[8]

–Games of Superstition (ritualized wildness). Superstition admits no belief in law, unity, or reason; it embraces the notion of chaos, yet nevertheless qualifies that certain methods or choreographies somehow harness arbitrariness better (learning to play to the anarchy of things). To that end, one can even refine relations to luck (via practices of intuition, reaction time, hypothetical thought, and by studying routes of the ricochet).

–Games of Narrow Victory, Landslide Victory, or Pyrrhic Victory (based on varying protocols of “satisfaction”, and also differing definitions of “excess”).[9]

–Games of Changing Levels or Roles (where hierarchies, positions, and identities are continually shifted throughout and restore players to a zero-degree). Musical chairs; costume-parties; those card games of rotating kings.[10]

–Games of Distraction (based on temporary escapism: the masquerade, rave, or hallucinatory trip that always guarantees return or homecoming) versus Games of Concentration (play that demands all-consuming immersion; games that become the world; games that take forever; games where obsession drowns out the player’s loyalty to whatever past, beckoning oblivion and radical forgetting of all else).[11]

–Games of Clues/Signs (where we search hidden tells, reading imperceptible patterns: the puzzle; the riddle; the scavenger hunt; games of immanent deciphering).[12]

–Games with Dealers (where we encounter mechanistic intermediaries: the tarot card reader; the blackjack dealer; the supposed impartial). Notice that the dealer is often blamed for the cards, and this is indeed a correct intuition, because they do serve the house, and the house must always win, though the evil of their collaboration is dulled by the more metallic look of probability.

–Games of Territoriality (where the specific locus is chosen by one side, thereby affording experiential or psychological advantages).[13]

–Games of Boasting (where bravado, swagger, and competitive taunting are integral) versus Games of Courtesy (where respect, formality, or even ceremonial silence are demanded).[14]

–Games of Infinity (endless lives; reset) versus Finitude (all-or-nothing; one-shot deal). As a formulation that seamlessly threads together these two precepts, the Japanese leagues of the ancient Chinese game Go are reputed to have a special room called Yugen-no-Ma (a word with connotations of shadow, subtlety, obscure elegance, “mysterious depth” or “mystery at the light of day”) where only the highest-level masters are allowed entrance and are rumored to channel hallowed ancestral senseis therein.

–Games of Addiction (where the game increasingly becomes an obligation, need, or neurotic compulsion). This occurs when the ludic figure declines from techne to technics, which as another philosopher once said denies letting “the earth be an earth.”[15] It is also distinguished by the decline of pleasure into mere release from pain—for which one might say that existence itself, and particularly its drive to perpetuation, is the first game to fall sway to this addictive degeneration.[16]

–Games of Style (where each player develops a singular performativity, something distinctive or improvised, and where victory itself depends on realizations of originality, craft, or rarity). Here players must become inimitable or iconic to prevail.

–Games of Entering the Opponent’s Mind (hyper-anticipation). First Question: Is the opponent tactical or whimsical? Here one should definitely consult with those early pagan thinkers who contemplated dealing both with scheming gods (operating from plans) and temperamental gods (volatile, impulsive), thus requiring the correct identification of the gamemaster as either diabolical overseer or unreliable force, for it decides whether one is reading steps or moods.

The Game Is Lost

We remember that Socrates and many others pronounced philosophy an ars moriendi (art of dying), and that even Camus said that the only philosophical question worth asking is whether to kill oneself. Yet how do we elude Caillois’s integral measure that a game must prove voluntary, especially when we know from existentialism that being itself is conceived in thrownness, which by definition would mean that we are not in a proper game? That is, unless there is actually a way to make it so after the fact: no doubt, this is how the advent of extinction gives us the absurd freedom to wrench existence into the voluntary (not at its origin, but at its terminus): stated simply, we do have the power to stop playing the game, or to lose it on purpose.

With that premise established, is there not an ecstatic dimension to this equation as well, one that makes us search for the intimate relation between fatality and eternity? Nietzsche at the conclusion of Thus Spoke Zarathustra talks about the “drunken joy of dying at midnight” at the same time that he says “Was that life? Well then! Once more!”[17] He also defines ecstasy therein as that bizarre outer boundary where one simultaneously cries “How could I bear to go on living, and how could I bear to die now.”[18] To enter into this ever-revenging circular imagination, however, one must abandon rigid logic and instead take a deranged walk with storytellers: for example, Shahrzad, from The Thousand and One Nights, who in order to keep staving off her own execution at dawn, each night recounts these cliffhanger tales of intrigue and cruelty that continually extend the duration of the end forever. In other darkly meditative corners, Emile Cioran said that the thought of suicide carried him through a lot of bad nights—the exact quote being something like “Without the idea of suicide, I would have surely killed myself.” So it is that those of us who frequently deal with end-of-days poets and philosophers of the lost cause can tell you this: the trick is that the recurring narration of doom scores our suspension in a kind of infinite finality. In effect, it buys us time before the absolutism of the final breath by making the last moment everlasting.

Nevertheless, this fatal-eternal paradox requires us to distinguish between the many chambers of loss itself, for which only a condensed diagram is provided below:

Games of Intentional Loss

–Affective Loss (where sensory intensity is highest for the player who fails; games of hide-and-seek or chase, where all exhilaration compresses into the moment of breakdown). This is the thrill found only in dread, the gasp of: 1) the being-caught; 2) the close-call.[19]

–Strategic Loss (where the rewards in defeat supersede the formal decision of the game).

–Artistry (where one seeks the aesthetic challenge of losing in unparalleled fashion).[20]

–Glory (where one defines climax as spectacular death upon the field).[21]

–Bribery (where one takes a fall for reasons of alternative compensation).

–Nihilism (where one purges or incurs loss in order to clear way, though without delineated horizon, whether from simple exhaustion with the state of things or as a means to aerate the terrain of possibility).[22]

–Martyrdom (where one loses in order for something else to win). Martyrs whose sacrifice is a conscious payment/trade to seal another’s triumph; or those servile characters who betray the human race to aid the rise of the inhuman (alien, wolf, image, demon, machine).

–Conspiracy (where one offers themselves as bait—the easy target; the waiting-to-lose—in order to lure others into the grip of the larger waiting pack).[23]

–Playing Multiple Hands (where one makes several incursions and retreats, combining paradigms of irregular warfare and criminal versatility, staging eruptive plots here and there in scattershot formations—not a centralized revolutionary process but rather a procession of disparate, fragmented, shape-shifting escapades). Extinction also benefits from these (non)settlements of flux by wagering itself on only one activated trigger coming through in order to collapse the totality of the real. This is the chronic advantage of evil—that not everything has to go right; just one stake has to hit and catch fire—using indeterminacy and the lone exception to crash the game’s entirety.

–The Long-Game (where one specifically loses in the short term in order to seek windfall in the long run: the shaky logic of rebels who believe that the final successful revolution will redeem all prior struggles, thereby justifying casualties and blood ad infinitum along the way; or those great creative loners who wore the mantle of historical losers in their eras, risking alienation or persecution, in order to engrave their names into the gameboard of existence against all odds).[24]

–Disguised Loss: (where one cleverly dissimilates strength/simulates weakness in order to reverse situations or wield surprise: e.g., those prophets, assassins, and martial artists who wore robes of the beggar or acted physically crippled in order to seem vulnerable and thereby seize control of the game). Thus the disguise negotiates a bridge between pseudo-abjection and violent revelation.[25]

Against this backdrop of the vanquished, we might also recall that the earliest civilizations—Babylonian, Sumerian, Egyptian, Persian—simultaneously devised creation fables and apocalypse fables: thus they were imagined alongside one another, which marks a remarkable closing of the circle at the very juncture of its opening. We have to ask what these ancients—who encountered mortality at every turn in the jaws of famine, night raids, tribal war, natural disasters, susceptibility to disease and outlandish infant mortality rates—suspected intuitively about this human experiment with time, consciousness, and destiny. Perhaps they had the accelerated vision of the Decadents who saw the sprawling presence of skeletons among living bodies: in essence, that it is over already (as good as done). This also allows us to speculate on how the concept of inevitability fuses into our discussion of risk, games, and hazard—not to mention an entire network of play tied to carnivalesque indulgence (the banquet, the feast, the amusement park, the circus, the bonfire, the festival). Beneath their surfaces of frivolity, we somehow always sense that we are watching an end-of-the-world show.

Furthermore, in entertaining these many corridors of loss, we stumble upon the potential for a paradoxical inversion of our original two themes: Insurrection as a gateway to extinction (have we not seen the revolutionary promise that mutates quickly into gulags and death camps?), or extinction as a form of insurrection (is there not a rebellious potential hidden at times in devastation?). Oedipus’s defiant gesture of tearing out his own eyes makes him the blesser and curser of cities in his later years; and the same with Cain, the first human (born outside the garden because his parents are the subjects of a lost game or failed test) whose status as primordial lawbreaker wins him the touch of the accursed. Interestingly, the Devil’s bet against God is itself also a story where a failed rebellion is tied to an extinction outcome: in that the Devil becomes the agent of Hell (extinction-zone of the soul), but still a gambler caught forever in this computational race against the divine (philosophy of spite) to steal as many hands and hoard as many human spirits like cards or gamepiece tokens until Judgment Day. Hence the boundaries between insurrection and extinction—the saving of the world and the killing of the world, the roar of the masses and the mass grave—are invariably blurred.

Years ago, I was tempted by the vague image of a third god (of stone-cold neutrality and irreversible desertification): namely, a figure with zero interest in good or evil, creation or endtimes, origin or futurity, punishment or salvation, life or death, who would have slept through Genesis and turned a blind eye to Armageddon, and with equal indifference toward the collection/distribution of souls that comprises the race to apocalypse. Their lone temporality would be that of aftermath; their lone spatiality would be that of the wasteland; their lone desiring-function, to rule over the non-world that arises. Let us wonder what it would mean to perceive the games of insurrection and extinction before the inexistent altar of this figure, which might require us to inhabit the silhouette of the anonymous player: the blank domino; the wild card; the skeleton key that opens all doors because of its radical smoothness. More on this for another time, though.

References

[1] Gilles Deleuze, Public Talk (Le Fondation Femis) on Cinema: What is the Creative Act?, 1987.

[2] Roger Caillois, Man, Play, and Games (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001).

[3] There is an old saying in various cultures that our relation to mortality itself is like playing a great master: that we are inexorably destined to lose, but still want to give it a good game (in the meanwhile). Examples of such endurance-testing procedures are: the rodeo (where riders count the seconds before being kicked off wild bulls); children’s breath-holding or staring contests; or at a more cosmic level, the prediction of the red giant sun, where supposedly in 5 billion years the star’s outer layers will scorch the oceans and consume earth and other planets, which then trivializes all action to a short-lived venture.

[4] Piracy has cheating built into its very cultural substructure: sidestepping, theft, deception, and betrayal are all assumed parameters.

[5] Waiting ultimately becomes an essential experiential facet of these games—for instance, the lottery dictates that one buys the ticket (in advance) and then remain stalled in some helpless unknown until the climactic occasion arrives.

[6] Certain animal species have the instinctive ability to double-back when hunted, thus confusing trackers by disturbing the sequential legibility of their traces. Some early psychoanalysts also advised our turning back toward our nightmares, meaning to run in the direction or even bite down on the apparitional figure of fear.

[7] Casino culture houses both elements of suddenness: spontaneous victory can be found in the spinning reels of the slot machine, and spontaneous destitution in the bad dice-throw of the craps table.

[8] Jorge Luis Borges’s “Library of Babel” poses an architectural infinity of enigmatic books where one can spend years wandering its corridors or even lifetimes lost searching in its hallways for the single answer behind the Library or the Universe: some go mad, some form occult devices, some devise highly intricate numerologies and interpretive schemas, but some exasperated types just start deciding where to look based on dice-throws. They sit in corners and allow the twisting instrument to determine whether to turn right or left, high or low, aligning motions according to intentional randomness.

[9] There is a certain megalomania that can unlock itself during gaming campaigns: this often results in a euphoric subject who conceives of themselves as the greatest player to ever grace the game (the paragon), and each opponent as the second most talented player in existence (the arch-rival), for this mindset vivifies all potential outcomes.

[10] We can imagine the tea party of Alice in Wonderland and its constantly-switching seats, but also another short story of Borges titled “The Lottery in Babylon” where identity is renewed each night as people draw lots to swap titles/destinies. Thus, on any given evening, one can become the slave, apprentice, gladiator, dancer, god—unchained to fulfill all potential desires or fantasies for the simple cost of an equal willingness to accept being a plaything of others’ wishes amid those rounds of devaluation.

[11] Fairy-tale arcs typically conclude with the child’s return to the real, though for illicit purposes of smuggling traces of the unreal (they always remember the fleeting diversion), whereas an example of the latter (all-enveloping play) can be found in Herman Hesse’s Glass Bead Game which describes the futuristic inception of a game of extreme sophistication developed by neo-esoteric schools that seek to bind together all variations of thought through unexpected connections. Here, everything becomes the all-synthesizing game.

[12] Note that the inventor of the puzzle or riddle is a benevolent torturer, in that they ultimately hope for its solution.

[13] This also adds to our discussion the important component of the crowd or audience.

[14] War harbors both concepts depending on timing/circumstance: the hour of the rally-cry versus the hour of humility, truce, or mercy (collection of the dead).

[15] Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art” in Poetry, Language, Thought (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013), 17.

[16] Is the dream of extinction itself a proposed cure to this first drug-game (of the desperate need to keep living)?

[17] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra in The Portable Nietzsche (New York: Penguin, 1982), 431-434.

[18] Ibid., “On the Vision and the Riddle”

[19] Again this refers to the aforementioned will to masochistic defeat. Adventure, in both its classical and unique sub-genres, combines precisely these two principles in a pendulous convention: that of always being on the run (the fugitive) and just barely evading menace (the escape artist). Astonishingly, one can also find this excitation in the maniacal infant’s toy of the jack-in-the-box, where a grinning joker springs loose at the apex of some eerie melody.

[20] Consider those auto-destructive movements who set fire or poured acid on their own artistic products, or the Japanese author Yukio Mishima who planned his own ritual beheading in an arcane theatrical scene of troubling detail.

[21] The ancients perceived heroic glory as something equated with dying young (in order to attain immortality), which follows the same paradoxical logic of monstrosity in horror: Are the vampire, ghost, zombie, or mummy not precisely those who perish in the most brutal ways in order to achieve supernatural status as the undying? Moreover, consider those precarious figures of the fight or gamble who play their best but increasingly want to lose (the archer, the racecar driver, the mine-diffuser). These are figures of incredible precision and accuracy: and still, the more one approaches perfection, the more a sinister curiosity develops to deviate or miss the mark. They keep tempting themselves closer and closer to fatal error (driving nearer to the wall); they make the conditions harder (shooting with a blindfold or one eye closed); they make the chances of survival or victory more unlikely (caressing the wrong wire with their scissors). For this embodies the final stage of exaltation: after all, the standard of becoming godlike (apotheosis) is not only to be able to create and dominate a world, but also to be able to destroy it.

[22] This is almost akin to thieving God’s propensity for flooding or burning landscapes/worlds in order to reset the game of creation.

[23] Children’s street-gangs use this asymmetrical strategy in superior fashion, manipulating the appearance of innocence in order to overwhelm with later numbers.

[24] Antonin Artaud refers to this unstoppable echo of the condemned or the crucified (in their own time) as antidote to the nothingness that “laughs at us at first, lives off us later.” [Antonin Artaud, Selected Writings (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988), 516.]

[25] In Kung Fu traditions, the Drunken Fist or Drunken Boxing school of zui quan derives from a Taoist myth of the Eight Drunken Immortals, where fighters imitate, feign, or enter actual intoxication and employ techniques of successive feinting, stumbling, swaying, and bobbing to catch their opponents off-guard.