1

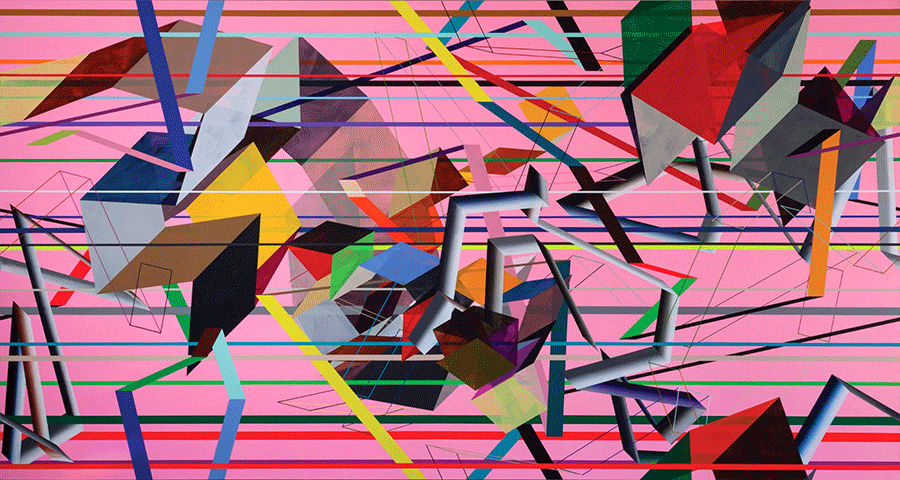

Imagine describing the series of Jeff Perrott’s paintings New Construction (Pharmakon, Subject, Natural, Denatural, Door, Sublime, Red Interior, and Cosmic) to an AI or a blind person. How would you start? By listing which elements come first, and how the layers of lines in each painting are ordered?

Describing an artwork is deconstructing or disintegrating its total aesthetic experience into interpretable and comprehensible pieces and components. It is an analytical process that involves dividing a complex problem into simpler components and transporting it from one cognitive plane to another so that the viewers can comprehend the work’s complexity.

Humans, with their ability to see, can experience art visually: Through their cornea, the reflecting light from the surface of the work is focused onto the retina, which then flows as neuronal messages to the viewer’s brain. AI and blind people cannot follow this process. Not because they cannot value or even understand a painting but simply because they cannot sense art visually. Although we can build robots with visual sensing that rely on algorithms or models to make them sense and interpret the paintings, this action is similar to explaining a figure to a blind person. We use verbal language in the case of the blind person or programming language, which can be said to be verbal, in the case of AI.

In programming, you can divide the code into three steps:

1. The universal space, where variables are declared and OOP1 objects are coded;

2. The declaration of variables or the objects themselves;

3. The setting up of actionable functions, which the objects are performing with the defining help of variables to perform in the code.

AI’s understanding of an artwork takes place in the continuous field and the universal space of algorithms where the construction, reconstruction, and scaffolding of visual elements, like lines, shapes and colors, occur.

This logic is applicable to Perrott’s works since they involve an infinite plane covered in white, color or black; they are depicted on a “continuous field,” comparable to Deleuze’s plane of immanence.2 According to philosopher Peter Wolfendale, “everything that is situated on the plane of immanence is conditioned,” therefore constructed, and “everything is conditioned just in the sense that everything is produced out of and situated within networks of causal interaction;”3 On these planes of immanence are layered the artist’s “hard-edged axonometric geometry”4 or “parallel perspectives,”5 constituting inferential rules through which architectural forms are then constructed. The action of the elements, follows a random move function or method6 through an extrusion process,7 where two-dimensional objects gain a 3D character or impression. As soon as the viewer is ready, they can press “Run,” and the code will be executed. Then comes the moment when, as Eva Hesse claims, “[t]he formal principles are understandable and understood.”8

The difficulty we would still face in regard to understanding the work lies not in its form, execution or its embedded syntax, but in its semantics or the logical inferences between what is seen and what can be known about what is seen. What unfolds within this dialectics is a certain architectonic drive within painting that is not far from what Kojin Karatani called the “will-to-architecture,”9 the tension between a purely formalist project versus an art predicated on sensation and free creativity, and also between physics and mathematics versus aesthetics and signification. The architectonic quality of Perrott’s series is such that it bypasses this tension by engaging with contingency through scaffolding. According to the artist, this process is based on three main steps:

I’m strictly using hard-edged axonometric geometry, or ‘parallel perspective’ which develops quasi-architectural forms. Second, I’m wrapping the compositions, or continuing forms from one edge of the painting to the opposite edge, taking the picture plane as a continuous field. And third, I’m using the random walk process—the direction of each successive shift or joint connecting the geometric planes is determined by chance. So, there’s a plan, which includes contingency.10

It is this stake that is at play in Perrott’s creation of “non-hierarchical painting,”11 while the artist embraces difference and equality in full, in the manner he calls radical difference and equality,12 using Nelson Goodman’s concept of worldmaking through the method the philosopher calls addition.13 In Perrot’s words: “[the painting] is additive, as opposed to reductive, it continues as opposed to stopping, it’s promiscuous instead of redemptive.”14

The inferential construction of the impossible through the addition of possibilities, chances, and indeterminacies leads us to the artist’s own question: how can anyone construct the seemingly impossible if not only through the imaginative.15

2

Although made in acrylic on linen, there is a case to be made for the presence of an algorithmic construction of shapes in Perrott’s work, which reminds us of the history of computer graphic interfaces. What is at stake in this relation is how the appearance of shapes in both forms a broader commentary on the current status of abstraction and representation.

Engineers and computer scientists developed the Graphical User Interface (GUI) to translate human gestural aesthetics into the binary code of computers. A striking feature of Perrott’s work is precisely the recreation of this algorithmic procedure through painting, which has been identified both as the quintessential formalist medium and an escape from formalism’s constraints through free expression and autopoiesis. Perrott recasts the concept of the interface with the medium of painting while identifying it with our own contemporary and tangible problem of human-machine interfaces at large.

Human-computer interfaces as we know them today date back to a Cold War military project known as Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE), a system that coordinated data from many radar sites to produce a single unified image of a wide airspace, and later to the subsequent research conducted by the Xerox corporation in the 1960s. Both of these developments were pioneered by an engineer named Joseph Carl Robnett “J.C.R.” Licklider. Licklider’s theoretical work contributed to the invention of interactive laser-guided missile launch pads at the end of World War II and culminated with his contributions towards the invention of the desktop and mouse for Xerox’s Star Operating system between the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Licklider’s “Man-Computer Symbiosis” from 1960 and “The Computer as a Communication Device,”17 co-written with Robert Taylor in 1968, document his vision for both human-computer relations and the future of computer-to-computer networks.18 Licklider believed that the main intellectual advances in the future would be made not by artificial intelligence alone but by “men and computers working together in intimate association.”19 Unlike early cyberneticians like Norbert Wiener and Alan Turing, Licklider wasn’t thrilled about the prospects of a machine-dominated world. Instead, for him, it was human-computer relations that intellectually constituted “the most creative and exciting activity in the history of mankind.”20

Both Wiener and Turing had previously compared machines and human consciousness in their theorization of information technology, but it was with Licklider that these two essentially different and separate systems and bodies meet and melt into each other.

Licklider viewed the process of communication as a comparison made between communicating parties about their own individual “mental models”:

By far the most numerous, most sophisticated, and most important models are those that reside in men’s minds. In richness, plasticity, facility, and economy, the mental model has no peer, but, in other respects, it has shortcomings. It will not stand still for careful study. It cannot be made to repeat a run. No one knows just how it works. It serves its owner’s hopes more faithfully than it serves reason. It has access only to the information stored in one man’s head. It can be observed and manipulated only by one person. Society rightly distrusts the modeling done by a single mind. Society demands consensus, agreement, at least majority. Fundamentally, this amounts to the requirement that individual models be compared and brought into some degree of accord. The requirement is for communication, which we now define concisely as “cooperative modeling” —cooperation in the construction, maintenance, and use of a model.21

Licklider recognized communication as a form of collective thinking and sharing ideas whose success rests upon the creation of a communal model through which this process can take place. He saw computers as the vehicle for this process:

[The computer’s] presence can change the nature and value of communication even more profoundly than did the printing press and the picture tube, for, as we shall show, a well-programmed computer can provide direct access both to informational resources and to the processes for making use of the resources.22

In this sense, the relation between Perrott’s New Construction series and contingency illustrates this particularity of what cannot be represented by the technical image. It thus shows what is particular to the space of thought occupied by the collaboration between human consciousness and that of the machine as realizations of Licklider’s vision of human-computer symbiosis. Each artwork represents a unique mental model, presenting a complex, coded interplay of lines, forms, and colors that engage the viewer in a dialogue of meaning-making. The paintings mimic the structure of GUI with their geometrical architectonics, paralleling the space of interaction between code and interface where the reshaping of visual elements occurs. The “continuous field” in Perrott’s works echoes the universal spaces of coding but also of the computer screen, creating a visual language that integrates the thought of information into an optically unified frame.

Perrott’s use of chance in his “random walk” process mirrors the inherent unpredictability in human-computer interactions. His algorithmic construction of shapes can be seen as a reflection on Licklider’s idea of “cooperative modeling.” Each painting thus becomes an interface of communication as such, embodying a complex system that invites viewer participation in interpretation, actualizing Licklider’s vision for cooperative, creative activity between humans and machines.

The developments in interface design parallel those in the second wave of cybernetics in which the computer was thought to stand between humanity and the world, and the computer interface was theorized to facilitate this communication in real-time. Thus, human consciousness was perceived not so much as a representation of the world but as its reconstruction, a temporally contingent model for a better understanding. The function of the interface in an uncertain epistemology in which the observer is a determining part of the system was supposed to clear the intuitive cloud and replace it with a tangible presentational model that could both be aware of its arbitrariness at the same time that it assertively stood in for the world.

Perrott’s artworks, as representation of the world and also as an exercise on worldmaking, are a reconstruction of the new through an already-made structure, as they enable this temporally contingent model to open up the space of thought or reason. In this sense, we encounter a world in which the figures interact through a certain self-contained logic. However, the procedure of making such logic itself is connected to a form of contingency directed towards assessing the participation of indeterminacy in its own self-critique. What propels Perrott’s works beyond the tradition of abstract painting is the fact that they exhibit neither an empty fascination with nor a rebellion against form, but stretching the compositional capabilities of the medium towards abstract worldmaking.

3

As painting in the early 1960s moved away from chaotic and psychologically charged abstract expressionism to geometrically organized minimalism, the task of calculating the shape and the placement of geometric objects in this new breed of paintings was digitized and assigned to electronic machines. 1959 saw both the arrival of ANITA (acronym for A New Inspiration to Accounting), the first electronic calculator at Great Britain’s Bell Punch Co., and Frank Stella’s early “pinstripe” paintings, included in that year’s show, 16 Americans, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

It is not hard to imagine that the commercially available calculators that had started to enter all facets of life were also used by artists in the proliferation of geometric and minimalist paintings and sculptures of the 1970s which were mushrooming as the new artmaking trend around the world. If, as Laurine Daston and Peter Galison23 argue, the invention of photography mechanized and automated the production of the scientific image, freeing the artists’ hand from their previous obligation toward a realist and objective representation of the world, widespread use of calculators liberated artists from the daunting labor of calculation in formalizing their images in the picture plane. If abstract expressionism was a conscious form of abandoning the outer world and embracing the noise-induced world of the unconscious, minimalism was not only a representational but also philosophical about-face, in that the movement’s interest in mathematics and geometry was these areas’ embracing of rationality and systems, which if not directly relating to the objective physical world was at least an abstract attempt to understand its invisible underpinnings.

Our ancient capacites to generate and utilize form as pictorial representations has been ramified since the dawn of GUIs in the history of digital graphic design tools like Adobe and other more contemporary AI models such as Midjourney, DALL-E, and GAN.

Adobe Illustrator, for example, first released in 1987, is a vector editor that enables the creation of scalable illustrations and artwork. It provides precise control over shapes, colors, and gradients, making it an ideal tool for creating abstract geometric designs. With Illustrator, designers could easily create and modify complex shapes, allowing for the exploration of abstract concepts and the creation of unique visual representations. Through their user-friendly interfaces and powerful capabilities, graphic softwares have democratized design and made the field more accessible to a broader public.

We ought to note that the development of graphic applications marked also a different disposition to what could be done and count as innovative in terms of constructing images having forms as their building blocks, as graphic forms became the primary means of the interface between man and machine. Not only has there been an exponential increase in the usability of computers but also a certain new aesthetic disposition which connects certain forms as more to the genealogy of the internet. Everywhere, rectangles abound (usually landscape mode but increasingly more verticalized), while the interaction with them migrated from writing to the mouse, touch, voice commands and more recently to Virtual Reality and AI. These multiple entry points made formal elements less allusive and thus attractive. Even more crucially, diagramming the experience of existing in the post-internet universe became an even more difficult task since we find ourselves within a convoluted yet rigid field.

While an interface in cybernetic theory does not connect two different entities but puts in contact the two separate portions of the same process, Perrott’s paintings are the medium for implementing a procedure of painting that at once erodes the distinction between human and its medium of expression, revealing what is singular about human reasoning while embodying the historical evolution of computational technologies in parallel with the history of abstract painting. These paintings, like the geometric minimalism of the 1960s and 1970s, involve calculations and arrangements while mirroring the principles of early computer graphics interfaces.

4

James Vincent, a journalist of The Verge, an American media outlet focused on technology, claimed in 2019 that “[t]he images created by GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) have become the defining look of contemporary AI art.”24 GANs are machine learning applications based on the research and development works of Ian Goodfellow and his colleagues. Today, some of the most proactive GANs developed and marketed by two of the biggest AI research laboratories are DALL-E, by OpenAI, and MidJourney, by an independent research company. These applications can be understood as a game of two conflicting neural networks: While the former is generating different images trying to fool a second neural network, the latter is trying to discern what is coming from the generative network against the “real” world stemming from the vast available datasets. In this process, two competing models fight each other to achieve a singular goal; training the generator model leads to new and better outputs—in this case, synthetic images that are yet to exist in the datasets. At the same time, the training of the discriminator model leads to increasingly identifying the images synthesized by the generator instead of those existing in its datasets.

GANs are in essence similar to the Imitation Game that inspired Alan Turing in formulating the Turing Test in which a machine tries to fool a human by displaying intelligent behavior. Except, in GANs, both networks collaborate to discern what is and is not real. As their output to the user, they present similar but different and new images compared to what already exists on the internet. It is in this nuanced difference that the creative effect of GANs manage to attract and impress their users: As these input text as a prompt, the two models begin to compete until they create a new image representing the input visually as close as possible.

Perrott’s artworks are Post-GAN art in the sense that it would be impossible to generate such artwork from any possible input even though the procedure that produces them can be described as an algorithm. By parallels with different stages of the ongoing cybernetic revolution like algorithms, pocket calculators and graphic softwares, I am highlighting how Perrott’s New Construction series doesn’t actually function as a single set of signifiers but that it embodies a compressed history leading to a new strategy for post-digital practices. If GANs and older computational systems involved with visualization function as machine recreations or automation of human physical and intellectual labor, Jeff Perrott’s series is a conceptual schema through which the work of the machine is carefully reversed back into human cognitive and physical labor and recorded on the canvas as a historical object charged with signification and meaning—called painting. Much like how the generative and discriminative models in a GAN system contend in a competitive back and forth of creation and validation, Perrott engages in a similar race with the machine. These paintings transcend painting to become a physical record of a profound interaction between humans and machines. Here, Perrott offers a unique perspective on the future of art in the AI era, defying and upgrading our understanding of painting and art in relation to technology.

* Kunstwollenn is a concept that, in German , literally means ‘will to art’. It was created by theAustrian art historian Alois Riegl , who understands it as a force of the human spirit that gives rise to formal affinities within the same era, in all its cultural manifestations.

Notes: