*Originally delivered as a response to Gertrude Stein’s “The Making of Americans” on Day 27 of Superconversations, a collaboration between e-flux and The New Centre for Research & Practice in 2015.

The most recent wartime Christmas in New York was as cold and bright as any other holiday season had ever been in the city. As usual, a row of shining black limousines lined 51st Street, between 5th and 6th Avenue. The briskly-walking passersby looked on at those entering Rockefeller Center, where an exclusive holiday party was taking place within. Little did they know, however, that this year’s party obscured a darker, if equally cold, logic.

While downstairs in the main lobby a VIP Party celebrated the latest advances of the Allied forces in Europe, upstairs on the top floor members of the political and cultural elite from English-speaking countries had gathered to privately discuss important matters. In fact, the big party far below at ground level was only organized so that its publicity could camouflage why so many important people were gathering in the same place at the same time in New York, for this top secret and highly-exclusive event.

Around a simple but large wooden table, reminiscent of both Shaker and modernist furniture, in the all-glass board room situated in the middle of the Executive Suite, Room 3603, on the top floor of the International Building North of the Rockefeller Center, a group of men and women were meeting to discuss the future. It was a gathering of a variety of odd characters at the charged intersection of art, money, literature, geopolitics, and counterintelligence.

To bring multiple quips from around the table into a focused discussion, Alfred McCormack, the only military officer present in the room, turned to Abby Aldrich and, referring to the recent Picasso & Matisse exposé at the Museum of Modern Art, asked, “How was the exhibition of the communist painter boys from Paris?” While Abby was trying to come up with a diplomatic response, Clement Greenberg turned to the general and said, “Actually, those were only replicas. Isn’t it a pity, but at the same time intriguing, that we don’t really know how to tell real modern art from fakes in America?”

Alfred immediately continued by adding, “This brings us to why we are here upstairs worrying about art and culture while others are downstairs celebrating our recent military victories. However, since I am not an expert in cultural affairs, I think we can expect David to brief us a little as to why, in addition to our military power, we might need to think a bit about alternate arsenals for the challenges America faces in the world after our final victory over the Nazis in the future.”

After looking intensely into the eyes of his best friend and relative, John Foster Dulles, David Rockefeller made brief eye contact with those around the table and began speaking:

“Hello and thank you for accepting my invitation. You may not all have visited this building before, so I am glad you are finally getting a chance to witness how my late father helped build one of the world’s new wonders in the heart of our international empire. The task we are attending to tonight is no less monumental or detailed than his and, like the construction of these complex buildings, it involves a fine balance between form and function. We are here to discuss the future of art and creativity, not only in the Western hemisphere, but also across the entire globe. Even though there can be no doubt that we have been sincere in cooperating with the Communists to beat the Nazis and win this war, none of us should have a doubt in our minds that this alliance is temporary and that as soon as we are done with Hitler, a fierce competition will ramp up, whose outlines will perhaps define the shape of the rest of the 20th century. However, since our inevitable future struggle against Communism cannot be won with arms alone, we seem to have a fundamental weakness which sooner or later will hamper our future development as a world superpower. To put it bluntly, most artists and thinkers in Europe and America are against our American virtues, and instead have sympathies for our future enemy. Since the onset of the 20th century, Bolsheviks and Communists have had the upper hand in the world of art and culture and it is necessary for our future success that American values replace Communism as the driving motivation for the production of an emerging world culture. More so it is crucial that the center of artistic production be moved from Communist Europe to America – or more precisely, from Paris to New York. We are here to brainstorm and think about ways in which America can implement this monumental task.”

George Orwell who, until now, was perhaps the quietest person around the table, not engaging with anyone at all, suddenly turned to the speaker and said: “Cold War my friend, Cold War. This will be the term for describing our engagement with international communism in the future. And if David allows me to go on, I’d like to add that I don’t think there is anyone around this table tonight who thinks art and culture are inconsequential matters in relation to these Cold and Soft Wars which I predict will be played out mostly in the fields of information and cultural exchange.”

Sitting next to Alfred Barr was Clement who used the silence after George’s declaration to turned to him and ask, “But by this you don’t mean a literal pro-American propaganda campaign in the style of socialist realism I hope, and since there can be no better time suited for expressing my honesty than this important occasion, I have to say that I am not so fond of the way you have so far approached the issue at hand in your own literary work. I read your manuscript for Animal Farm and let me tell you, your message in this book is so literal that I am not sure it can even affect readers above grade 5. I sincerely think that if we want our efforts to be effective, we might have to exercise a more refined subtlety and even actively avoid direct references to Stalin and his gang.”

William Stephenson, while doodling on a piece of paper with his expensive Parker pen suddenly stopped to look up and ask, “Why not both? Why can’t literature perform this task literally, and art metaphorically? I think we need to work both on the average person as much as those well-versed in the arts. George’s work might not be suited for the second group but can come in handy in preparing the first of those to really understand our postwar challenges.”

As one of the only three women present at the meeting, Eleanor Roosevelt used this moment to jump in and add: “We also have to make sure that whatever it is that we are doing does not come across as blatantly affirmative of the United States. There are a large group of artists and intellectuals on the Left who can be explicitly or implicitly recruited for our camp if our intentions are presented as a purely leftist attempt. To do so, we need to isolate the hard leftists, I mean the Communists and the Soviet sympathizers, from the soft leftists who conflate their liberal principles with the utopian ambitions of Communism. Not only do we need to exploit the rift between these two groups, but also we must make clear how liberalism is more humane and, in effect, able to offer a far superior alternative to Stalinism than any other available set of ideas. We ought not to worry too much about the communist posturing of our intellectuals so long as they stand with us against the Soviets in the last instance. In fact, their interpretation of the reformist essence of the American spirit with the revolutionary core of communism can be exploited to our benefit, ensuring that our younger generation remain American in the depth of their identity with only a thin layer of communism covering the outer surface of who they think they are.”

Immediately after Eleanor, Abby added, “This is so true! It reminds me of how I always used to tell my late husband to not be afraid of communists and instead give them money and encourage them to make political art or write literature instead of organizing real political actions. I bet there are only a few revolutionaries out there who would not prefer the ease and happiness involved in building a fictional utopia over the pain and frustrations involved in the building of a real one.”

John Foster Dulles returned to the table after having taken a break to talk on the telephone for a few minutes, remarking: “I am here to remind you that this task needs collaboration and coordination. Unfortunately, given the sorry state of the Congress, the Army’s intelligence office and other national security apparatuses are the only arms with access to the resources and the know-how around the world to connect the private sector and government forces together, and to try to stir this cross-platform effort in the right direction. We’ve got money, we’ve got talent and we’ve got manpower, and we want to end the dominance of communism over modern art and make it American…”

A voice from the other end of the table finished John’s sentence, adding, “… and dialectically, America itself would finally become modernized in this process.” This was indeed the voice of none other than James Connan, who until very recently was being held in prison on sedition charges related to his efforts organizing American workers against the war, and whose arrest had been supported by the pro-Stalin Communist Party of the United States. James Connan, William Phillips and Clement, who were sitting next to each other, were the only people in the room aside from Eleanor who knew what the word dialectic meant.

“Good idea!” blurted Alfred, “I’d better not forget this wonderful insight from James.” Proceeding to reach into his briefcase to pull out a folio containing photographs and sketches, he continued: “But the most important question on which we have not spent any time is how we shift the political connotation of modern art without damaging its historical continuity, which, as with any other form of culture, is preserved in the progression of its aesthetic development.”

Clement quickly added his bit while Alfred passed the folio around the table: “Well, we need to work hard, at least for a decade, on producing good American artists, both in terms of an actual workforce and also in terms of this workforce’s interaction with the specific publics engaged with what we call Art. During this decade, we need to slowly move away from every aesthetic element that has so far identified American art, that awful lady and her Whitney Museum, and instead work not only on cultivating the aesthetics of European art, but to extend it in the direction we see as serving the best fit for the America of the future. We already have a dozen of very bad or very basic modern painters like Hartley, Davis and Benton, if not also O’Keefe and Harper. Still, unfortunately, they cannot be heirs to European art since they lag behind and are only tangentially related to the newest artistic developments in Europe. They represent nothing but different levels of kitsch as far as true modern painting is concerned. Their work, as significant as it may seem to us from our provincial point of view, will hardly capture anyone’s attention in Paris or London. We need a brand new group of young artists for this task, and the question becomes one of what direction, from the ruins of art in Europe, we hope they might take on.”

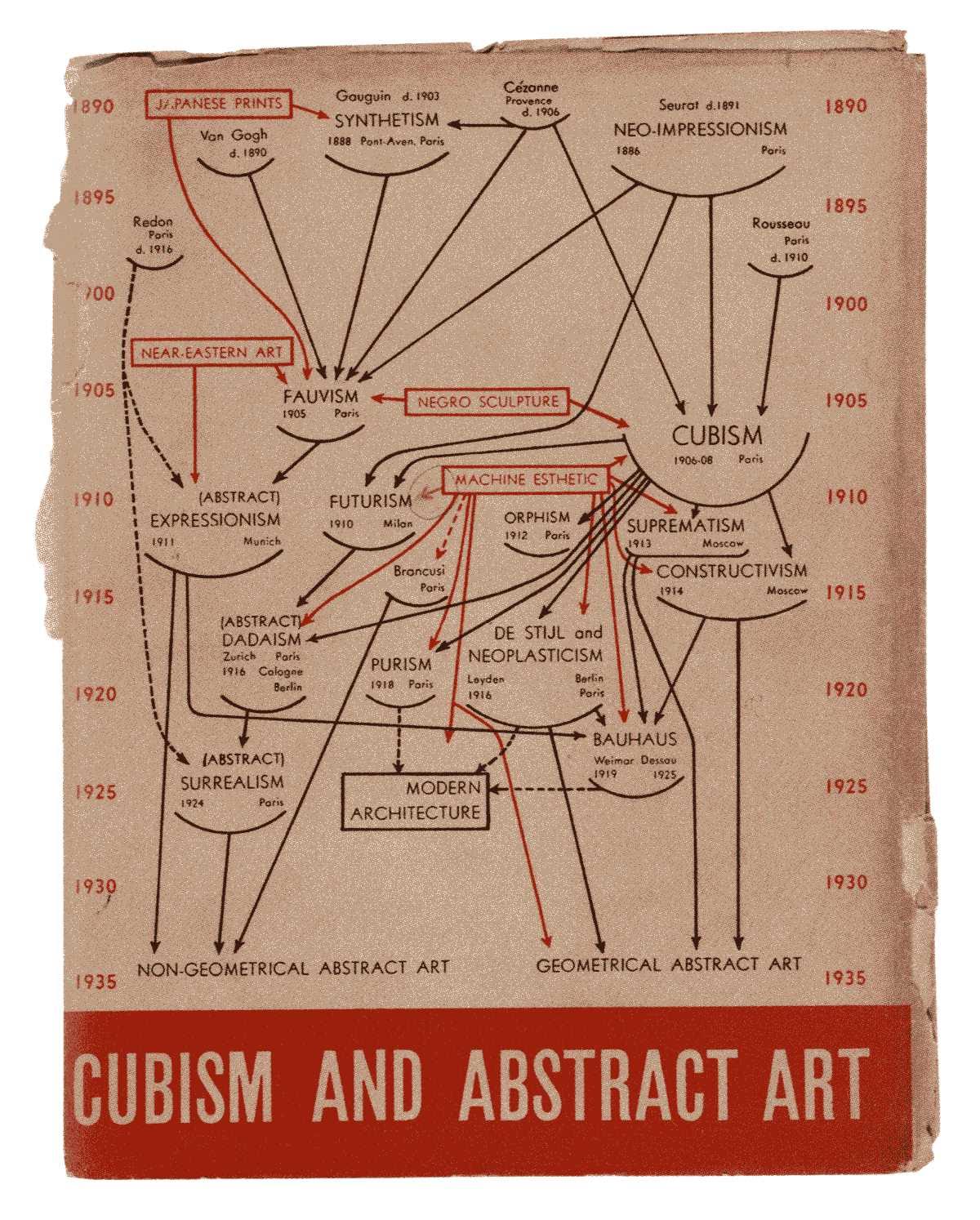

Alfred then added: “To address what Clement just brought up, if you take a look at my Modern Art chart from a number of years back, you’d see how, based on my study, European art has already provided a few options in terms of how American art can pick up where Europe left off, because of the war, and move forward. In my opinion, we can develop our national art as a model for the rest of the world from one of these trends or their combination. On one side we have non-representational abstraction, which came out of a long trajectory of artists trying to resign the traditional role of the artist to the new technologies of photography and cinema and go the opposite direction. On the other side of the divide, we have Dadaism and Surrealism, which share a similarly whimsical and poetic basis. While Surrealist images are easily understood in relation to older traditions of paintings, their dependence on the new science of psychoanalysis pairs them tightly with sexual themes. On the other hand, Dadaist art, which might look and feel similar to Surrealism, goes far beyond the present concepts of what art and the artist are, and arrives at everyday life to find not only inspiration but also solutions to larger social or even political issues which might surface as a result of further modernization. In my opinion, the toughest of the three strategies for American artists to adopt for further development is the pure abstraction which comes either from Kandinsky’s painterly textures or Mondrian’s geometric patterns. I recommend that to build a new American art, we ought to avoid the alienating, non-representational, abstract forms and instead encourage our artists to play with forms emerging out of Surrealism and Dada in order to forge a true modernist American art.”

Clare Luce, who was accompanying her quiet husband Henry, suddenly threw Alfred’s portfolio on the table, and raised her voice: “Alfred are you pulling our leg? If you really think Surrealism and Dadaism are the way to go, I have some news for you: America is a Christian and conservative nation and there is no way an American art laced with such sexual and socially corrosive content will be able to be digested by our population, as it trickles down to the masses. Contrary to your opinion, if anything, those meaningless abstractions, as alienated as they seem, are better suited for our two-tiered society in which the elite and the masses have often gone their own ways in matters of taste. These fuzzy paintings and checkerboard canvases might not be appreciated by the American philistine, but at least they do not mean much when it comes to their core religious and or personal beliefs.”

Over a long silence, the folio, at last, completed its journey around the table and returned to Alfred’s hands. One could now hear an escalating murmur in the room. It seemed that the meeting was going to end the way it started, except a loud voice now enunciated itself, the voice of Clement, who stepped in to finalize the conversation: “I know this sounds strange, but as a critic, I have to say that my gut feeling is to support the only real Republican in the room. Clare is right. The meaningless abstractions of Kandinsky and Mondrian are much better suited for what we can pursue as a truly American form of art after the war than either Surrealism or, worse, Dadaism, which I abhor the most. It is not that I recommend that we censor or ignore these other movements. Instead, we need to assign them a marginal place in the cannon while including them to highlight the inclusivity of our conception of art, and our institutions like MoMA. I suggest Alfred take an interest in these types of art for the museum’s collection to ensure that they never take center stage in art history by other institutions in Europe or South America. They are best suited for smaller galleries and perhaps the hallways of the many American Modern Art museums.”