Why is it so difficult to simply begin with the definition of violence?

-Judith Butler (2017)

This essay will redefine the terms of violence in order to produce a useful terminology for the politics of resistance. This will be achieved in three stages:

1. The proposal of the problem of violence

In the section “The Problem of Violence,” I will introduce Slavoj Zizek’s distinction of subjective and objective forms of violence. Here I will characterize the main problem that burdens the philosophy of violence, namely, the glossary of violence suffers from inherently partisan and equivocal definitions of terms. In view of that, I will introduce Thomas Hobbes’ and Freud’s descriptions of violence as examples of analytical misrecognition of de facto violence. By discussing Walter Benjamin’s concept of divine violence, I will then stress the philosophical requirement—and difficulty—of describing a purely ontological form of violence, which is motivated neither culturally nor politically.

2. Investigation of the problem of violence

In the section “The Graph of Violence,” I will introduce a graph, which will allow me to superimpose Slavoj Zizek’s distinction of subjective and objective forms of violence onto Carl Schmitt’s distinction of the friend and enemy. This graph will maintain that the scholarly interpretations of violence are often very predictable and conceptually one-dimensional. The brief exploration of Franz Fanon’s and Hannah Arendt’s descriptions of violence will further justify the architecture and terminology of the Graph of Violence.

3. Solution proposal to the problem of violence

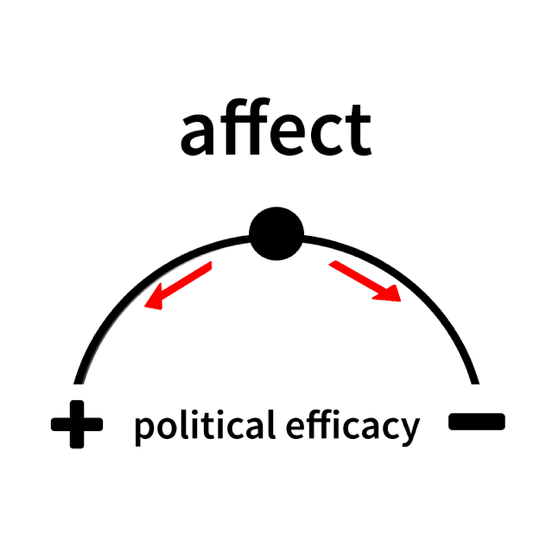

In the section “The Graph of Affect” I will introduce a contrasting graph, which will restructure the terms of violence by way of affect theory. Here I will show how Slavoj Zizek’s distinction between objective and subjective forms of violence utterly dissolves during major political events—effective circulations of affect. The term ‘violence’ will henceforth be exchanged for the term ‘affect’ as this will allow me to interpret violence as a form of affect, which is neither superior nor inferior to other forms of political affect-production. I will achieve this by following Massumi’s, Bertelsen’s, and Murphie’s descriptions of affect in politics. By focusing on the affect—rather than on violence—I will emphasize the necessity of managing tactical circulation of diverse sets of violent and non-violent affects within the politics of resistance.

The Problem of Violence

When analyzing the issue of violence, we are struck by the enormous misunderstanding as to what violence is. That is to say, the philosophy of violence lacks clear-cut systematization of specific violent acts and their respective purposes. At first glance, the act of violence should seem quite straightforward; that is, it entails a purpose, a perpetrator, and a victim. However, under a closer look, it becomes clear that the attempt to grasp the purpose of an act of violence is a partisan and therefore, an equivocal venture. When claiming that a violent act has a particular purpose, one is inevitably making a politically motivated value judgment. In other words, the very act of framing a violent act and its purpose is an ethico-political imposition of the norm. Slavoj Zizek’s dichotomy of subjective and objective violence proves this point in that he perceives violence as a consequence of an inherently capitalist system (2008, 27). The issue of violence is thus connected with the topic of late-capitalism, thereby establishing an adversarial political frontier between himself and the “ruling system.” To recap, Zizek claims that subjective violence has an identifiable agent who perpetrates said violence, whereas objective violence is systematic; that is, it does not have a tangible, observable agent. Furthermore, Zizek describes the ‘objective’ violence as that which “is ‘real’ in the precise sense of determining the structure of the material social processes” (2008, 24). By using such rhetoric, he insists that the ‘objective’ violence is common to all people, it is capitalist by nature, and it functions even when people are not aware of it. To put it another way, Zizek claims that even if one does not experience the objective violence, such violence nonetheless functions. This results in a tautology, namely, Zizek’s unique contextualization of objective violence renders all people who are unaware of such violence absolutely oblivious. The problem here lies not in Zizek’s argument on violence—a very valid argument at that—but rather, in the lack of elaboration in his thought as to what violence ultimately is. Though it is clear that Zizek works to evaluate the modes of violence—its uses and purposes—he, however, shies away from the discussion of violence hic et nunc.

To strip away violence of its cultural purpose is not a simple feat; i.e., violence generates rooted hierarchies as well as tight relations of cultural reciprocity. That being said, the notion of violence does possess an integral quality of naturalness, which manifests itself amid the visceral sensation during a violent act. Thomas Hobbes ascribed violence to the very nature of man when he claimed that people, within the natural condition, use violence “to make themselves masters of other mens persons, wives, children, and cattell” (2012, 96). If we followed the naturalist idea of metaphysics, the conclusion to Hobbes’ argument would be self-evident—physical violence should be perceived as an innate, pre-conscious motivation, which incentivizes people to pursue domination ad libitum. Such an argument falls right at the center of the Freudian framework, wherein violence is described as a biological fact, which needs to be repressed so that human civilization could prosper. Civilization guarantees, according to Sigmund Freud, that a “sense of guilt could be produced not only by an act of violence that is actually carried out but also by one that is merely intended” (1962, 84). Here, however, we unearth the same diagnostic impasse, that is, we are still unable to separate de facto violence from violence de jure. Hobbes and Freud are describing the natural condition of violence as a precursor to civilization or the lawful social contract. It should be noted that neither Hobbes nor Freud undertook an analysis of violence per se without the reference to its cultural purpose. In Hobbes’ terms, violence serves a clear function, namely, domination. In Freudian terms, similarly, violence serves the function of biological impulse; i.e., the natural aggressiveness and sexual drive. Therefore, what is needed now is an analysis of violence without a reference to its purpose. In other words, we need to rake out the notion of violence as an immediate visceral experience that is devoid of cultural motivation.

Walter Benjamin, in his critique of violence, describes purposeless violence by introducing the notion of divine violence (2007, 278). According to Benjamin, legal violence is a means to an end—a violent act with a legal purpose. He arrives at this conclusion by analyzing natural and positive forms of law, both of which undertake to prove the appropriateness of the means of violence vis-a-vis the ends of violence. In other words, legal violence is caught up in a rigid deadlock in that it tries to justify the means by justifying the ends and vice-versa. Such an attempt of justification certainly does not possess an objective standard of measure. For this reason, Benjamin thinks that legal violence always lacks sufficient criteria for justification. The only way to confront so-called legal violence, Benjamin claims, is divine violence, a violent act without a purpose functioning as pure means. Zizek follows Benjamin’s assessment of divine violence in that he considers purposeless violence to be a legitimate mode of political emancipation, which could be utilized by the exploited class. For example, during the French revolution, the violence of the people was an expression of utter desperation and disillusionment with the ancien regime ( Zizek 2008, 283). This stands as a good example of divine violence in that French revolutionaries were simply acting out their sociopolitical predicament. In Zizek’s terms, these revolutionaries successfully undermined the objective violence by engaging in an act of divine violence with no clear-cut political ends in sight.

Having considered Benjamin’s notion of divine violence, I would now like to pose a question: does the notion of divine violence tell us something of value about violence hic et nunc? It is my view that the notion of divine violence—similarly to Hobbes’ and Freud’s views of violence—simply reacts to the problems posed by objective violence, or civilization. The only difference is that divine violence is not a precursor to civilization but rather an antecedent, that is, an attempt to transform the civilization. Even though Benjamin’s notion of divine violence is an extremely compelling undertaking to understand pure (purposeless) violence, it does not tell us anything about the immediate experience of violence.

Here, we should consider Maurice Blanchot’s rumination over the notion of disaster. For Blanchot, disaster should be considered as an occurrence that remains outside of all presence. That is, disaster (violence) traumatizes victims in situations that are beyond the political representation of purpose. “The mark of disaster,” Blanchot writes, “is that one is never at the mark except when one is under its threat and, being so, past danger” (2015, 13). In other words, the political notion of violence can never describe violence hic et nunc, and it can merely estimate violence before or after it occurs. As Hegel noted, “The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk” (Hegel [1820] 1991, 23). This means that the contextualization of violence always comes forth already late. The problem with violence is, therefore, quite straightforward—we cannot grasp what violence is. For this reason, the notion of violence is consistently misinterpreted by thinkers of various political faiths. The people who shed blood for political gains can perfectly well exalt the same soundbites apropos violence, which are dear to law-abiding iconoclasts—the people who use the term ‘violence’ mostly as a slogan. The notion of violence, therefore, requires a new nomenclature that could present us with more creative strategies of political dissent; i.e., we need to (re)define our terms.

However, before a clear terminology can be reified, we should examine more carefully the main problem of the philosophy of violence, namely, the way in which it relies on a basic dichotomy, that of the friend and enemy. This dichotomy alters and contains all facets of the philosophy of violence, and more importantly, it alters how we interpret the distinction between the subjective and objective forms of violence. For this reason, the Graph of Violence (see Figure 1) was devised to help us visualize the equivocal nature of the definitions of violence.

The Graph of Violence

The elaboration of the Graph of Violence (see Figure 1) should commence with a consideration of Carl Schmitt’s famous argument: “the specific political distinction … is that between friend and enemy” (2008, 82). That is to say, Schmitt thought that the fundamental distinction that motivates people within the public political domain is that of the friend and enemy. By locating their friends and enemies, political agents are able to fashion their endeavors strategically. Within the Graph of Violence, the friend and enemy distinction is illustrated by the vector a. Such visualization (a) of the friend and enemy distinction will allow me to mark the exact point at which a distinct interpretation of violence positions itself in relation to its potential field of friends and enemies. As it was hitherto emphasized, the metanarratives of violence tend to be partisan and equivocal, and therefore, it is imperative to locate interpretations of violence—precisely and unequivocally—on the vector a. The reason to begin this analysis of objective and subjective violence by discussing Schmitt is very simple: the distinction of objective and subjective violence cannot escape the friend and enemy distinction. These two dichotomies perpetually reciprocate and motivate each other.

Now, we should take a look at the vector b, which represents Slavoj Zizek’s distinction of the objective and subjective forms of violence. In Zizek’s view, an individual (subjective) form of violence should be distinguished from the systemic (objective) form of violence. The Graph of Violence, however, emphasizes the impossibility of demarcating a clear division between the objective and subjective forms of violence (b) without maintaining a clear division between the companionable and adversarial political forces (a). To reiterate, both of the vectors (a,b) in the Graph of Violence respond to each other.

With this in mind, let’s take Zizek’s interpretation of violence as an example. Zizek claims that people are prone to fixate on subjective violence because it functions as a spectacle, that is, people can immediately identify the purpose, the perpetrator, and the victim of a conspicuous violent act. The problem, Zizek claims, arises when people try to identify the nature of the objective violence, which transpires inconspicuously on behalf of the state and capitalist institutions. Naturally, objective violence is much harder to identify for it is deep-rooted within the system. Zizek, therefore, insists that objective violence should be taken more seriously as it often determines “the fate of whole strata of the population and sometimes of whole countries” (2008, 27). This idea maintains that if people are to direct their dissent towards anything, they should direct it towards the forces of objective violence, begging the question: who precisely are the agents that are responsible for the objective violence? Zizek identifies the neoliberal economic consensus, the capitalist globalization, and the members of the liberal global elite (so-called liberal communists) as the main forces, which are responsible for the objective violence. We can immediately locate these forces in the Graph of Violence (see Figure 1). Zizek’s critique of objective violence positions his enemies—neoliberals and liberal communists—on the far-right side of the vector a. In addition, since Zizek is focusing on objective violence, vector b falls to the bottom of the graph. For Zizek, therefore, the objective violence locates itself at the right bottom quarter of the Graph of Violence, which is termed ‘objective unjustified.’ In this case, Zizek perceives objective violence as an unjust force that should be critiqued and ultimately countered.

Here, another question arises, namely, how should one counter objective violence? This is precisely where the Graph of Violence is useful . By locating the bottom right quarter of the Graph of Violence as the object of Zizek’s critique, we can immediately locate the opposite side (friend) of the graph as the method of countering the unjustified objective violence by utilizing subjective violence (justified). The Graph of Violence, therefore, represents the utterly inefficient terminology of the philosophy of violence. The dichotomies of Friend-Enemy and Subjective-Objective encase the discourse of violence into a binary system of readymade solutions. After Zizek establishes the objective violence as his object of critique, he is left with a preposterously simple solution—to either counter objective violence (unjustified) with subjective violence (justified) or with non-violence. Interestingly, Zizek entertains both—subjective (justified) violence and non-violence as viable progressive reactions to the pestering objective ‘unjustified’ violence.

Zizek mentions Herman Melville’s ‘Bartleby’ as a symbol of non-violent feedback, which relies on withdrawal from immediate political action and violence, and, thus, maintains that sometimes the most radical political gesture is to do nothing (2008, 299). Therefore, while fighting the objective unjustified violence, people should use caution and critical analysis; i.e., they should refrain from uncontrollable action—precisely the non-violent reaction that is lauded by Zizek. With this in mind, we can observe that the Graph of Violence can indeed be subverted in that the unjustified violence does not always result in the aggrandizement of justified violence. However, this way of subverting the Graph of Violence turns out to be absurdly superficial, as it is a quasi-subversion by withdrawal to non-violence. Therefore, a non-violent reaction to the Graph of Violence is not an act of disarticulation of the Graph of Violence but rather a form of simple resignation from it. For this reason, it would seem that the philosophy of violence is utterly skewed by the one-dimensional terminology of violence. The interpreter of violence is forced to organize his/her analysis by choosing the terms off-the-rack; from violence and non-violence, friend and enemy, subjective and objective distinctions.

The inept terminology of violence becomes even more problematic when Slavoj Zizek discusses Walter Benjamin’s concept of divine violence. Even at its face value, Benjamin’s concept of divine violence does not make a clear distinction between violence and non-violence, that is, it is never clear whether divine violence describes strictly physical violence or strictly non-physical violence. Zizek, unfortunately, does not make that distinction clearer for he describes revolutionary divine violence as a form of violation—often non-violent—of the ideological norms of (neo)liberalism and democracy. Zizek even goes so far as to claim that, in the precise sense of divine violence, Gandhi was more violent than Hitler because he actually revolutionized the system that was responsible for the perpetual escalation of objective violence. Hitler—on the other hand—did everything to facilitate the objective violence within the system. As Zizek writes, “Hitler did not ‘have the balls’ really to change things” (2017, 475).

Zizek’s analysis of divine violence forces us to conclude that the philosophy of violence lacks objective instrumentalization of specific means and ends of violence. The Graph of Violence presents us with a clear problem within the philosophy of violence; i.e., the majority of interpretations of violence function by constantly vacillating on the absurdly simplistic vectors (a and b) of The Graph of Violence. To illustrate this, I will discuss a few other examples of interpretations of violence, which are acutely trapped within the biunivocal dynamics of the Graph of Violence.

Frantz Fanon’s analysis of violence presents us with a unique issue, that of decolonization (2004, 30). Whereas Slavoj Zizek describes objective violence as a systematic force that is less conspicuous than subjective violence, Fanon describes a form of colonial violence that combines both the subjective and objective modes of violence. Under colonialism, the relationship of oppression—between the colonizer and the colonized—is intensely direct, visible, and immediate. The distinction between the subjective and objective modes of colonial violence, therefore, cannot be made clear-cut. Therefore, Fanon’s critique of violence emerges in the center of the vector b of the Graph of Violence; i.e., colonial violence utilizes both the objective and subjective forms of violence. Having in mind that Fanon is critiquing a brutal colonial regime, I should point out that his analysis locates violence on the far-right side of the friend and enemy vector a. To clarify, Fanon is describing a form of violence that is unjustified and functions on both the subjective and objective levels (see Figure 1). For Fanon, decolonization is “quite simply the replacing of a certain “species” of men by another “species” of men” (2004, 35). Here, the Graph of Violence becomes necessary as well—by locating Fanon’s description of colonial violence (vector ‘a’ far-right; vector ‘b’ center) we can immediately tell what his response to such violence will be. As I maintained previously, after one locates the object of critique (unjustified violence) in the Graph of Violence, one can select the opposite sector (justified violence) as a potential response. This approach works well with Fanon’s critique as he insists that decolonization is based on the replacement of men by other men. To put it differently, the unjustified objective and subjective forms of violence should be replaced—according to Fanon—by the justified objective and subjective forms of violence (vector ‘a’ far-left; vector ‘b’ center).

Now I would like to turn to Hannah Arendt’s analysis of violence in her essay “On Violence.” Here, Arendt differentiates two distinct political concepts, that of violence and power (1974, 44). Arendt claims that “power corresponds to the human ability not just to act but to act in concert.” That is to say, Arendt insists that power is a consequence of people acting together. Violence, on the other hand, should be “distinguished by its instrumental character;” i.e., violence is circulated by the use of weapons and other technological tools that are designed to increase strength (Ibid., 46). Here, we should turn our attention back to the Graph of Violence. Arendt claims that violence is unjustified insofar as it is the symptom of a tyrannical strength par excellence. As a result, Arendt’s object of critique should lie on the far-right side of the vector a, that is, the notion of ‘violence’ lies within the enemy sector of the Graph of Violence. Considering that violence, for Arendt, is circulated through weapons and technological tools, it seems reasonable to assume that she—similarly to Fanon—combines both, the subjective and objective forms of violence, into one. The point on the vector ‘b’ should, therefore, lie in the center. This begs the question: how does Arendt characterize the emancipating response to the tyrannical violence? Instead of simply describing a justified form of violence—as a response to unjustified form—she introduces a new concept, that of power. As it was previously mentioned, Arendt claims that power “springs up whenever people get together and act in concert” (Ibid., 52). She insists that power is non-violent, and for this reason, it can be easily frustrated by violence. Violence, for Arendt, “can always destroy power: out of the barrel of a gun grow the most effective command” (Ibid., 53). By using the term ‘power,’ Arendt makes a rhetorical gesture that conceals the clear-cut distinction between the justified and unjustified forms of violence as presented in the Graph of Violence. For Arendt, an organized group of people is inherently non-violent, that is, people that act in concert do not possess the machinery of state violence. The use of the term ‘power’ makes Arendt’s critique of violence especially unique. It would seem that Arendt understands the superficiality of the jargon of violence and attempts to utilize a new term—‘power.’ However, Arendt simply obscures the distinction between the justified and unjustified forms of violence, she does not undermine it. Indeed, an argument ought to be made that the use of the term ‘power’ further idealizes the justified forms of dissent. Such a critique would demonstrate that Arendt is nonetheless trapped within the terminology of the Graph of Violence.

The Graph of Violence proves to be a helpful tool with respect to Zizek’s, Frantz Fanon’s, and Hannah Arendt’s analyses of violence for it allows us to easily predict the conclusions of various critiques of violence. However, the visual representation of the Graph of Violence presents us with an aporia. As we are presently confronted with increasingly subtler forms of objective violence, the biunivocal categories of the Graph of Violence are becoming outdated, inefficient, and utterly unimaginative. After all, the most brutal and conspicuous forms of colonial and tyrannical domination have been mostly abolished. We will need to entertain new terminology of violence that is not based on strict dichotomies found in the Graph of Violence. I will now attempt to delineate such a vocabulary of violence, which will take advantage of the key ideas from the field of affect theory.

The Graph of Affect

As previously discussed, the philosophy of violence has yet to define its terms. We need to delineate such terms as violence and non-violence, enemy and friend, subjective and objective in a more unequivocal way. However, this can only be achieved if certain terms that operate within the philosophy of violence are unscrupulously disposed of and new ones are appropriated. For instance, the Graph of Violence (see Figure 1) symbolizes the very discourse that ought to be discarded. As I showed in the analysis of the Graph of Violence, the interpretations of political violence are often trapped within the biunivocal architecture of the Graph of Violence. As Deleuze and Guattari claim, “every concept shapes and reshapes the event in its own way” (1994, 34). The concepts of violence, therefore, also need to be reset insofar as new events of political action need to be furthered. For this reason, I devised the Graph of Affect (see Figure 2), which will stand as a clear alternative to the Graph of Violence.

The construction of the new terminology of violence should begin with an immediate disposal of the term ‘violence.’ The interpreters of violence often exalt violence as an efficient apparatus of dissent. However, the same interpreters often use the term ‘violence’ as a slogan in that they shy away from cruder definitions of violence and instead resort to the more elegant uses of cultural force. Such a tranquilized approach to violence unbalances the distinction between violence and nonviolence. More importantly, it cripples the imaginativeness of progressive political movements.

The following should be read as a self-evident truth: there is more to political action than a pitiful choice between violence and nonviolence. In fact, there is a multiplicity of affects—some of which are violent—that can be circulated in furthering a political cause. For this reason, I insist that the term ‘violence’ should be exchanged for the term ‘affect.’ The term ‘affect’ is a more general term, which defines a visceral emotion as an intensity that is passed from body to body, and therefore, can include the use of violence as one of its constituent manifestations. Furthermore, the theory of affect encompasses not only the most forceful intensities—violence and trauma being some of them—but also the most subtle, molecular encounters. Instead of the readymade jargon of violence (see Figure 1), affect theory introduces infinitely multiplicitous iterations of forceful politics. As a result, the Graph of Affect (see Figure 2) is extremely transparent for it encapsulates all dichotomies of the Graph of Violence onto a single vector ‘political efficacy.’ This means that The Graph of Affect is not caught up in the subjective-objective or the friend-enemy distinctions. All forms of affect-production are acceptable within the Graph of Violence as long as they efficiently multiply the encounters between bodies or—to put it differently—as long as they are politically efficacious. The amplitude of The Graph of Affect, appropriately, stretches from plus to minus. To clarify, the minus sign indicates a politically trivial affect, whereas the plus sign indicates the more efficacious one. In order to justify the outline of The Graph of Affect, I will now pose an example of an event that—by virtue of circulation of affects—proved to be politically efficacious.

Lone Bertelsen and Andrew Murphie discuss the infamous Tampa affair, during which the Government of Australia refused permission for the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa, carrying 433 rescued refugees (2011, 143). When the big red ship (MV Tampa) entered the Australian waters, an extremely poignant spectacle was erected. The whole motif of the Tampa affair lies in a singular display of bursting redness within a monotonous horizon of the sea. The big red ship in and of itself, without a doubt, is a very mundane object. However, the cargo of this ship, the 433 refugees, still managed to bring about an unprecedented political convulsion. As Bertelsen and Murphie note, the appearance of the big red ship became a metaphor for the threat of invasion from “Asia” (Afghanistan, Indonesia). Not only that, the big red ship carried with itself the gloomy stereotype of “Europe,” that of the “maternal Scandinavians with their welfare states” (Ibid.). The very doctrine of globalization violently entered the isolated Australian territories by way of the big red ship, which simply entered the Australian waters.

For Bertelsen and Murphie, the appearance of the big red ship functions as a refrain, which is described by Deleuze and Guattari as a territorializing force that structures temporary configurations of heterogeneous materials (2013, 302). With this in mind, the appearance of the big red ship can be interpreted as a new virtual potential, which estimates that something different in the socio-political discourse may occur. As such, the big red ship forced the Australian public and civil societies to reexamine the issues of globalization, race, and isolationism. Subsequently, the reaction to the big red ship triggered the redefinition of physical territories—such as circulation of bodies, management of borders and detention centers—and finally resulted in a redefinition of new existential territories, which include the institution of new laws and rhetoric (new modes of living and thinking). Given these points, the big red ship functions as “a refrain that potentializes other refrains” (Bertelsen, Murphie 2011, 142). Considering that the big red ship did succeed in establishing new virtual potentials, new physical territories, and new existential territories, it should be noted that— in effect—it constituted an event that employed affects efficiently. For one thing, the Tampa affair erased the dichotomy of subjective and objective forms of violence; i.e., the diverse set of socio-political consequences of the Tampa affair enveloped institutional forms of violence (objective) as well as individual forms of violence (subjective). For example, Bertelsen and Murphie claim that the Tampa affair “helped toward a general strengthening of states of exception in the increased demonization of ethnic groups, unions, the unemployed, intellectuals” (Ibid., 144). As such, the institutional demonization of refugees makes up the objective violence that ensued in the aftermath of the Tampa affair. In addition, the general aggressivity that was felt against refugees—after the Tampa event—opened the doors for subjective forms of violence. As Bertelsen and Murphie note, after Tampa, “everything became a matter of attack and defense” (Ibid., 144). The release of an affect in the form of the big red ship triggered a sequence of cultural and political developments that were—in very strict terms—both violent and nonviolent. That is to say, the repercussions of the Tampa affair were very diverse—some of them were physically violent while some of them less so. By looking at The Graph of Affect we can locate the Tampa affair on the affect vector as an extremely efficacious (+) event.

In the essay “The Future Birth of the Affective Fact” Brian Massumi observes, “we live in times when what has not happened qualifies as front-page news” (2011, 52). As an example, Massumi describes the events that transpired in the summer of 2004 when George W. Bush was campaigning for a second term as president. At that instant, the pressure mounted for Bush to admit that the main reason for invading Iraq, namely, the assumption that Sadam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction, had no basis in fact. Bush responded to this pressure by claiming that the decision to invade Iraq was still appropriate in that US was safer after the invasion than it was before the invasion; i.e., the US removed an enemy that was posing a future threat. As Massumi argues, the whole justification of the invasion boiled down to the following argument: “The invasion was right because in the past there was a future threat” (Ibid., 16). In other words, the potential danger of weapons of mass destruction never became a present danger. The invasion was initiated because of the threat of danger, an affect, was disseminated. Under these circumstances, can we claim that a manifestation of threat—an interpretation of an event, which did not yet transpire—still constitutes a violent act due to the potentiality of violence that may be circulated in the future? In other words, is it true that “we live in times when what has not happened qualifies as front-page news?” In answering this question, I don’t need to describe the mere observation of geopolitical threat as an act of violence for The Graph of Affect allows me to treat Bush’s scare tactics as an affect. Bush’s circulation of threat is an efficacious affect in that, like the Tampa affair, it generated new virtual potentials, new physical territories, and new existential territories. By calling it an efficacious form of affect I want to emphasize that the analysis of political affects should not be based wholly on the arbitrary imposition of morality in the form of friend and enemy distinction. In fact, the analysis of violence in politics should be, firstly, a strategic undertaking. As such, it should focus only on tactics that facilitate the construction of a major refrain, that is, the construction of territorialization that resets the virtual, physical, and existential territories. Violence, for this reason, should be interpreted as an activist’s tool in an extremely diverse toolkit of affects.

By selecting the Tampa affair and the Bush’s doctrine of threats as instances of efficacious affects I hope to show that seemingly trivial events can perfectly well initiate strings of consequences, which redefine ruling political ideals, ways of physical control (violence) as well as future laws and policies. The obvious issue here is that in both of the aforementioned cases the efficacious affects solidified state hegemonies, undermined egalitarianism, and escalated violence against the most vulnerable. This begs the question: how does one generate an efficacious affect, which would undermine the affects – like the Tampa affair – that pander to the oppressive structures of power? Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer to this question in that political activism requires localized analysis, swift adaptation, and a degree of pragmatism. That is precisely the reason why I devised The Graph of Affect. The political strategy of affect-circulation should be approached as a spectrum—not as a universal polarity (see Figure 1)—of maneuvers that range from objective to subjective uses of violence, from purely non-violent to purely violent forms of resistance. Most importantly, The Graph of Affect shows that we should be ready to adopt the enemy’s tactics just as we are ready to employ those of the friend.

Judith Butler claims, “I doubt very much that non-violence can be a principle if by ‘principle’ we mean a strong rule.” I would like to add here that one should always doubt if a single strategy—no matter what it is—can become a principle solution. In line with Bonnie Honig’s analysis, I insist that the circulation of affects should be interpreted as a circulation of a multitude of public things, “around which people may organize, contest, mobilize, defend, or reimagine various modes of collective being together in democracy” (Honig 2017, 24). Most importantly, these affects—or public things—may be used perfectly well for good and for bad. It is, therefore, up to every individual to decide what affects, what kind of violence, and for what reason does he/she circulate.

Violence functions just like Maurice Blanchot’s disaster in that it resists interpretation and it escalates despair. However, violence is also enveloped in a diverse set of affects, which we can actually scrutinize, circulate and—to a degree—control. If there is a group of people that is set on producing a decent political affect then I advise them to get it together and make it count; i.e., don’t use yesterday’s strategy and don’t make your affects predictable, instead—make them politically efficacious.

Works Cited:

Arendt, Hannah. 1974. On Violence. San Diego: Harcourt.

Benjamin, Walter. 2007. Reflections. New York: Schocken Books.

Bertelsem, Lone, and Andrew Murphie. 2011. “An Ethics Of Everyday Infinities And Powers”. In The Affect Theory Reader, 138-157. Durham: Duke University Press.

Blanchot, Maurice, and Ann Smock. 2005. The Writing of the Disaster. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Honig, Bonnie. 2017. Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair. New York: Fordham University Press.

Butler, Judith. (2016). Frames of war: When Is Life Grievable?. London: Verso.

———. 2016 “Distinctions on violence and nonviolence.” European Graduate School Video Lectures. https://youtu.be/3sSFCqzvTEI

Deleuze, Gilles. and Felix Guattari. (994. What is Philosophy?. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. 2013. A Thousand Plateaus. London: Bloomsbury.

Fanon, Frantz. 2004. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

Freud, Sigmund, and James Strachey. 1962. Civilization and Its Discontents. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1820) 1991. Elements of the Philosophy of Right. Translated by H B Nisbet. Edited by Allen W Wood. Cambridge University Press

Hobbes, Thomas, and Noel Malcolm. 2012. Leviathan. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Massumi, Brian. 2011 “The Future Birth of The Affective Fact.” In The Affect Theory Reader, 52-70. Durham: Duke University Press.

Schmitt, Carl. 2008. The Concept of the Political. University of Chicago Press.

Zizek, Slavoj. 2008. Violence. London: Profile.

———. 2017. In Defense of Lost Causes. London: Verso Books.