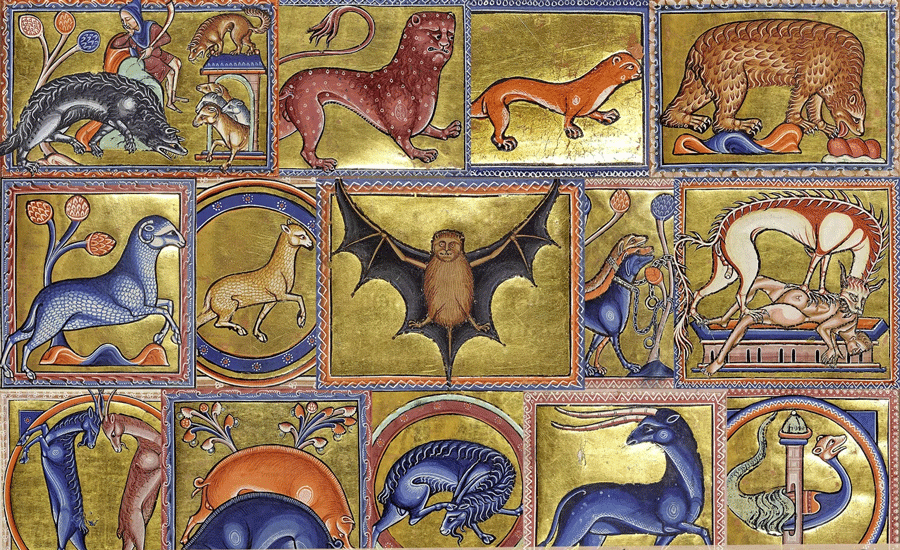

In this text, Eduarda Neves elaborates and expands on the critique of the contemporary artworld that underpins her book Minor Bestiary: Time and Labyrinth in Contemporary Art, published in English by &&& Books, available for purchase through here.

Minor Bestiary, my latest book, contributes to the debate about a few issues in contemporary art: the first part is entitled “Time and the novelty of impotence;” it is followed by “The labyrinth or why art has no beginning” and, finally, in the form of a post-scriptum, “Ice – at the end of the world, it is the universe that dreams,” reflecting on the relationship between art and tourism, an initiative developed in Portugal, 2022, (PORTUGAL ART ENCOUNTERS— PARTE Summit)1 with Portuguese artists and galleries associated with a certain international curatorial contemporary art mainstream. Although the reference authors in this book are from the field of philosophy, which is natural as this is my academic background, I could not fail to resort to literature, considering that it is in philosophy and literature that I like to situate what I write. Thus, Jorge Luis Borges, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Samuel Beckett, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, Martin Heidegger, Theodor Adorno and Peter Sloterdijk, are authors that have influenced me and that I quote frequently because I owe them a good part of what allows me to think. I don’t usually write against any author, trying not to waste my time with those whose work fail to encourage me. On the contrary, I turn to authors in whom my own thoughts find some possible affection and courage to keep believing in art and artists.

It is with these and other authors that I have started drafting an ideological x-ray of our time, one that provide us with the dominant traits of contemporary art: subservience to the authority of sponsorship, the aestheticization of social demands, exposure and activism tailored for Instagram, libidinal capitalism sustaining the economy of art, and the concept of heterotopia reduced to ambition, prestige and power.

Using the mythological figure of the Ouroboros, I sought to understand our time in political, economic, and philosophical terms as they relate to the field of art. Curators, critics and cultural journalists write for commissions by directors invested in financial patronage of collectors. The existing world of art, travestied as a more or less hidden, more or less cynical contempt, merges with the actual state of art.

In this situation, thought dresses the circuit of political economy in ready-to-wear quotations. Philosophy is domesticated, turned into decoration for the drumbeat of loud but hollow debates. Most of the political causes to which nothing escapes (post-colonialism, identity politics, feminisms, ecology, anthropocene and capitalocene, the cyborg and the kennel) tend to be consumed in so-called “events”, or, if we prefer, in the service of the status quo, the salvific rhetoric of art as spectacular teleology. The artist who wants to produce effect, to speak like Nietzsche, enhances the ritual of authority. The dictatorship of interests supports the art world and the growing pressure of interculturality and other symbolic branches multiplying an entire taxonomy of language that consolidates the best corporate work of the grammar of narcissism. In the same world in which “the fungus is the new superstar”, as was said about the 2022 Venice art biennale, the work of total art gives way to the total artists who claim to be at the same time anthropologists, biologists, ethnologists, and mystics. We are reminded of Salvador Dali who pompously wrote: “my art includes physics, mathematics, architecture, nuclear science, psychonuclear, nuclear mythology and jewelry”. Always the small narcissistic self, busy normalizing an art which is converted into demagogy while administering a staged metaphysical uprising; revolutionary exoticism.

These days the temporality of the Venice Biennale is more or less as flat as that of Swatch and Rolex. Meanwhile, if we want, we can find in the depths of the archive the brightness of phylum and ontogenesis, a time without beginning or end, a time for a minor art. To learn from the Nietzschean lesson, that is, to learn to forget; being against time but in time is still what we set out to do. This form of art is not therapy, nor a search for balance. It is in the poetic practice of philosophy and history against a dialectical program of the grand art of resentment, proposing a time of discontinuities, interstices, deviations, and spaces-times, where art can still possess the capacity of getting itself lost.

Between the mythological Ouroboros, symbol of unity, the Deleuzian philosophy that makes repetition the category of the future, the time of art in which there is no place for historicist or evolutionary dimensions, we find ourselves, following Prigogine, in the idea that time is not eternity nor eternal return. Perhaps we need another notion of time, one capable of transcending the categories of becoming and eternity. We seek, in this second part, and moving away from pure criticism of the institutionalized world of contemporary art, to reflect on artistic practices that do not logicize language, but rather approach poetics of heterogeneity and plural historicities capable of getting lost in the labyrinth of the Minotaur, closer to Pygmalion than to ascetic ideals. As Marguerite Duras wrote: who doesn’t have his Minotaur?

However, in this concption of art, the artist is not Theseus but the Bull, in which the labyrinth has become. As Hegel so well argued, labyrinths are paths intertwined between walls whose purpose is not to find the exit but to follow a winding path between symbolic enigmas. To think that we don’t think, yet. The “thinkable” as that which gives itself to thinking, as Heidegger wrote. Between the becoming and a certain minor art, a back and forth between Nietzsche and Deleuze. In this world, escaping from language, coding, indexing and organizing, — the fashionable claims of “healing” and “repairing” become purely grammatical claims, words with the weioght of a heavy century that painfully circumscribe the rhetorical device of classification.

Minor artists, a notion I take from Deleuze and Guattari’s text on Kafka, seek true temporary autonomous zones, in the manner of Hakim Bey, defying the internal law of things in the tradition of a certain poverty and a sacred and active deprivation. It will be up to them to make the desert and the abyss as new places far away from the eschatologies of the end — be it the end of art, the end of the world, the end of man, the end of capital. The minor art in which the labyrinth as a dithyramb glorifying the solitude of the sun in full light, opposes any commitment to tourism and the “good conscience” of oligopolistic financial capitalism that has conquered the world of art.

A minor art as Kafka’s lesson — that of the guard who is always waiting and aspiring to the Law.

Minor Bestiary: Time and Labyrinth in Contemporary Art, published in English by &&& Books is available for purchase here.