Introduction

The discipline of art history relies on the practice of preservation. The art historian typically understands the work of art in relation to an established canon, and this canon can only be referred to if its contents are in some way preserved. Yet any act of preservation is also an act of revision: material things decay, which means that at some point in the lifetime of a given artifact, efforts to preserve said artifact will necessarily involve supplementation. The preservationist is therefore tasked with deciding what to add, and what to remove from the artifact in question. This notion of preservationist as editor is complemented by Jorge Otero-Pailos’ definition of preservation as the organisation of attention.[1] For Otero-Paulos, the preservationist is responsible for showing the public which aspects of a work of cultural heritage are in fact deserving of focus. This centres the perspective of the preservationist; yet in what follows I will reintroduce the public perception of cultural heritage as integral to the work of preservation. This text will present three artistic interventions; each of which were constructed in the public sphere, and which existed only temporarily. With Otero-Pailos’ definition as fulcrum, I will show that these artworks can be understood as three different means of preservation.

Ahistorical Architecture

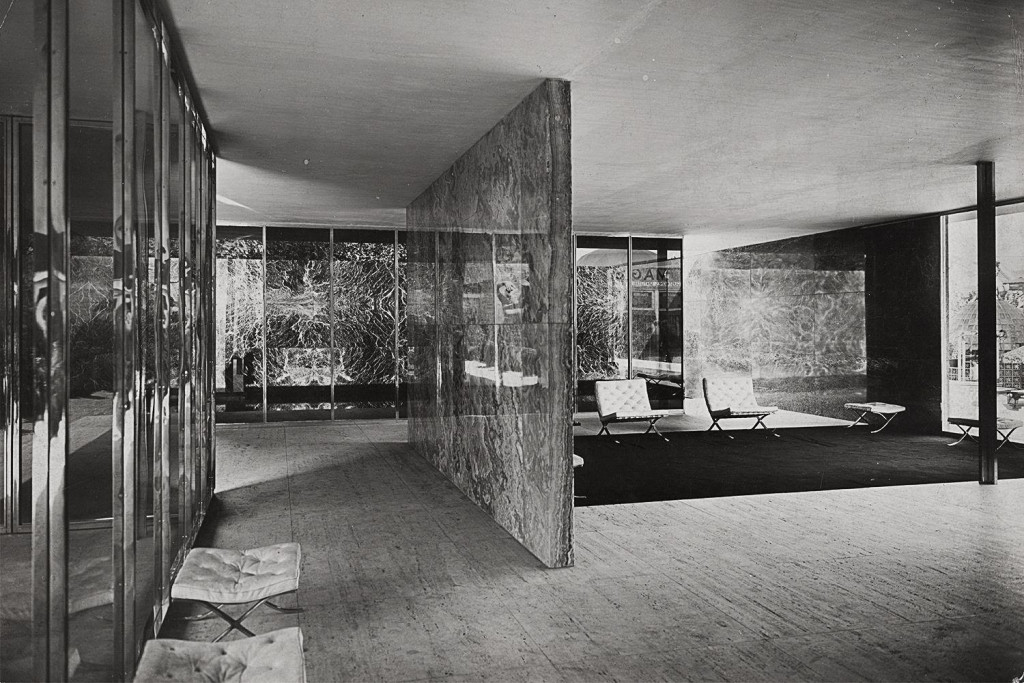

Central to the ethos of Modernist architecture was an understanding of the past as something to be surpassed. The movement, situated in the first half of the nineteenth century, was characterized by straight lines and simplicity of form. The Modernist effort to separate the present from the past was captured in the blank, white surfaces upon which an entirely new history could be projected. This historical division is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the apparent timelessness and purity of Mies van der Rohe’s 1929 Barcelona Pavilion. For Modernists like Mies, this new aesthetic was a more honest reflection of the technologies and materials that were available at the time. The pavilion features a low, flat roof sat atop 8 cruciform chrome columns, between which free-standing walls of precious stone demarcate an open-plan interior space. By supporting the roof on columns the walls could be placed freely, giving the building a spatial fluidity. This also meant that whole walls could be made of glass; the material was no longer confined to small windows as it had been previously. Indeed the roof itself didn’t need to be pitched or covered in roof tiles either; instead the pavilion features a roof that appears to float, one made impossibly thin thanks to the combined strength of concrete and steel. Thus by embracing modern techniques and removing historicist ornamentation Mies helped to define a Modern style that exuded a certain truthfulness: a style that was completely of its time.

Yet what quickly became apparent was that Modernism shared the same tendency for deceit as the Historicism that preceded it. The falsehood of Historicism was its basis in the realities of the past, while the falsehood of Modernism was its apparent baselessness. Modern architecture appeared to exist outside of time, and everywhere it was built it effectively retained the same aesthetic. In the Barcelona Pavilion, this notion of standing outside of time is further pronounced by the fact that the building standing today is in fact a 1980s recreation of the original 1929 temporary pavilion. The architects who recreated Mies’ design worked from drawings and photographs of the building and sought to develop a perfect recreation of the pavilion as it stood in 1929. The resultant pavilion has no place for anything that may spoil the appearance of being frozen in time.

The lavish yet sparse interior of the Barcelona Pavilion

The Contingent Spectre

Every building contains within it elements deemed unsightly; features from which attention is to be diverted. These are generally paraphernalia which complicate and detract from the overall image presented by that building. In the Barcelona Pavilion this includes anything that indicates the passage of time. Andres Jaque’s 2012 intervention, entitled PHANTOM: Mies as Rendered Society, is an effort to radically divert attention elsewhere and thus complicate this image. Jaque does this by uncovering the hidden inner workings that allow Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion to appear timeless and pure. The phantom that the exhibition title refers to is the basement hidden beneath the pavilion. For the intervention Jaque placed the assorted contents of this basement on display. When formerly useful pieces of glass became cracked or broken, they were taken down into the basement and replaced. These elements that were once a part of the upper floor became once again re-positioned above ground. Pieces of broken glass and chipped travertine, sun-faded curtains and worn-out seats are all placed on display. These elements are material witnesses to the passage of time. By putting them on display Jaque makes visible the temporality of the building; seeing a vacuum cleaner reminds us of the daily acts of maintenance and care. The pavilion is still cleaned after visitors go home, but the cleaning items are no longer retrieved from the basement below.

The building is a permanent reconstruction of a temporary pavilion, and the basement is a new addition introduced to facilitate certain functional aspects that were not originally necessary. Importantly, the history of the reconstructed pavilion has involved a process of trial and error. As interesting as this process is, evidence of it is hidden so as not to spoil the appearance of being a perfected object frozen in time. The pool in Mies’ 1929 pavilion housed water lilies in it, but the new pool was filled with chlorine. When it came to light that the original pool had water lilies growing in it, one gardener filled these glass boxes with fresh water in an attempt to reintroduce the lilies into the pool. While the lilies grew, they would die as soon as the petals touched the chlorine water beyond the box.[2] These glass boxes piled up in the basement chart this failed experiment; they contribute to the ongoing process of making the Barcelona Pavilion.

The building reflects an ethos of purity and timelessness, but this appearance is something produced anew each day. Jaque’s act of display reveals the way in which this convoluted basement allows for the ongoing functioning of the pavilion above. This relationship between the pavilion and its phantom is much the same as that between Dorian Gray and his portrait. In the story of Dorian Gray a handsome young man retains his youth and beauty by having all his aging and misbehaving recorded in his portrait rather than in his own face. Similarly in the Barcelona Pavilion it is the imperfections of the basement that allow the upper floor to retain its appearance of purity. By revealing the contents of this basement, Jaque reorganises the power dynamic between the two levels. He directs attention toward these elements of the pavilion, and in doing so he commits an act of preservation. With meticulous care and attentiveness, these discarded elements are brought to the surface. Jaque’s bold claim is that these unsightly and contingent components are as essential to the pavilion as are any other actors within the network that constitutes the pavilion. In this way the intervention does much to overcome the ahistorical perspective of Modernism. It broadens the range of what is visible, it accepts the minor and contingent, and should thus be understood as a progression. What must be avoided however, is seeing this work as entirely objective; as capital t True. It emerges instead from a particular editorial perspective; what is on display was selected to be displayed. The work is one of preservation, a form of archiving even, that originated in the architect’s engagement with the contents of the pavilion’s basement.

In PHANTOM, cleaning elements and broken building elements are brought up from the basement and placed on display.

Sacrificial Preservation

The editorial perspective of the artist or preservationist is of little value if it does not engage with the perspective of a relevant public. Those responsible for protecting cultural heritage must endeavour to allow the public to inform their decisions regarding what to protect. All too frequently, however, the infrastructure for dialogue between preservationists and the public is either insufficient or nonexistent. In these instances, the role of the artist can be crucial in facilitating such dialogue. One example of art used to mobilize public dialogue is Alfredo Jaar’s Skoghall Konsthall. In fact not only was public dialogue mobilised around Jaar’s artwork, but the existence of the artwork led to the formalisation of a new public.

In 2000 Jaar was invited to the Swedish town of Skoghall to produce an artwork, but when he arrived he found the town lacked any visible cultural or artistic spaces. In response to this lack he built an art gallery (konsthall), organised an exhibition of young Scandinavian artists to be shown in it, and then 24 hours later he had the building burnt down. The gallery was made of paper from the town’s paper mill which remains the largest employer in the area. Clearly Jaar had recognized a real cultural absence in Skoghall because as soon as he created the gallery, a group of citizens asked him to save it. The gallery was however burnt down as planned, with Jaar noting that he didn’t want to impose on Skoghall an institution that the town had never fought for. In burning the gallery Jaar made Skoghall’s lack explicit – he produced a void. Returning to Otero-Pailos’ definition, Jaar redirected the town’s attention toward the missing gallery. Long after the embers cooled and the ashes were swept away, this absence was still felt; so much so that eventually a group of Skoghall’s citizens got together and invited Jaar back to create the town’s first permanent konsthall.[3]

The beauty of this work is that thanks to this sacrificial nature it is non-impositional. The konsthall does not enforce a particular ideology, nor does it involve sermonizing or officiousness. In a strict sense it is useless as it cannot be bought or sold. Yet through the sacrificial spectacle of this work Jaar encouraged the people of Skoghall to imagine how things could be otherwise. The work encouraged Skoghall’s public to engage with the arts, but more importantly the work also helped to create a new public. The konsthall became a nexus around which a collective of culturally-hungry people came together. Through the work Skoghall’s public were imbued with a new sense of agency; they were invited to recognise their onus in the development of their town. Jaar was responsible for creating the art and reorganising the attention of the town, yet the greater task of determining what is worthy of protection was one on which both artist and public collaborated.

` Skoghall Art Gallery before and after being engulfed in flames.

Skoghall Art Gallery before and after being engulfed in flames.

Effigies & Publics

Skoghall is evidence of a model of preservation in which the values of a certain public are essential in determining what the artist as preservationist is to protect. In the Falles festival of Valencia, this model is even more apparent in that the sacrificial spectacle is repeated annually. During Las Falles, as in Skoghall, art objects are constructed and burned in a way that allows the public to reimagine themselves.

Every year, for a week in May, the city of Valencia is filled with huge artistic monuments called fallas. Along with admiring the spectacle of the fallas the celebration involves the near-continuous barrage of fireworks as well as musical parades, traditional costumes and lots of paella. The fallas themselves are made from wooden structures that are covered with cardboard or other combustible materials. Each one is elaborately crafted and depicts a number of figures either from the imaginations of the artists or from popular culture. Indeed this reference to popular culture is important as ever since the inception of the event the fallas have been used to satirize or criticize contemporary politics, often being anti-clerical or anti-government. In Valencia each neighbourhood has a group of people dedicated to the organisation and construction of a single falla, some of which stand more than 30 metres tall. At the pinnacle of the week’s celebrations the fallas are filled with fireworks and set alight. These sculptures burn brightly emitting light and sound but also giving off immense amounts of heat; with firemen in the narrower streets dousing the buildings and street signs to keep them from catching fire.

Countless artisans dedicate months of each year to constructing these elaborate sculptures, all in order to see them burn to charcoal in mere minutes. Yet once these sculptures are burned, what remains are the cultural narratives as defined by these collective acts of sacrifice. By revelling in the sights and sounds of Las Falles the Valencian people are involved in re-establishing the definition of being Valencian. With the creation and destruction of each new political effigy, there is an opportunity to re-examine local and global conditions and to take up a stance in relation to these conditions. Importantly this is not a task reserved for the artistic, but something that each neighbourhood is simultaneously engaged in. In Las Falles the object of preservation is the immaterial cultural heritage of the festival itself. And yet the centre of this celebratory sacrifice, the fallas themselves, are quickly destroyed – only to be labouriously reinvented and crafted anew the following year.

In Valencia, falles are burnt in front of joyous crowds.

Conclusion

To preserve an object of cultural heritage means augmenting that object in some way, and this augmentation necessarily stems from a particular editorial perspective. This perspective need not belong to a singular preservationist however, it can instead be bolstered by the input of an engaged public. In this sense, to determine what is culturally valuable requires constant re-evaluation. It involves a collaboration of public and preservationist in which agency continuously oscillates between the two. Yet to have a public that engages with questions surrounding cultural value, and to have such a public be audible, requires the involvement of other forces; namely, the artist. Indeed it is artistic interventions, such as those of Jaque or Jaar, that can help to mobilize the public in a way that engages them with cultural heritage. Through such interventions, the public are encouraged to weigh up the different aspects of a particular piece of heritage, and thus help the preservationist and art historian to determine what qualities of the work should be elevated and lauded (and which can be retained for their cautionary value alone – i.e. monuments of questionable historical figures). This performative assignment of value underpins all preservation efforts, and takes place even when the heritage in question is immaterial or absent.

Importantly, as with Las Fallas, Jaque’s and Jaar’s works are fleeting in nature, and it is their temporary existence which allows these works to function successfully as provocations. They do not replace what exists, but offer a glimpse at what else could be. Rather than unquestioningly reproducing extant norms, these three interventions demand conscious engagement. They encourage the revaluation of cultural narratives, and thus allow the public to push preservation forwards. By incorporating the views of such a public, the field of preservation is not restrained but instead challenged to experiment and reinvent itself.

[1] Jorge Otero-Pailos: The Ethics of Dust: Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Zyman, Daniela; Birnbaum, Daniel; Von Habsburg, Francesca (Koln: Walther Konig, 2010).

[2] From Underground Mies to Underground Storefront, StorefrontTV. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XpqAV-znPT4

[3] Chantal Mouffe, Agonistics: Thinking The World Politically (London: Verso, 2013).