Throughout its brief existence within the long trajectory of natural history, the human species has evolved alongside communication technologies which, according to the anthropologist Andrè Leroi-Gourhan, were developed only after we were able to free our hands and began standing and moving solely on our feet. Consequently, communicative signs were the offsprings of our liberated hands when we started to use our fingers to augment the real world vis-a-vis language. According to this theory, vowels were first modeled using stones (the so-called “amygdalae”) before being made into two-dimensional marks on a surface.[1] We also learned to directly virtualize the world by making external objects and images we call art.

A few millennia later, personal computers and the Internet have finally united the augmentation and virtualization/externalization of reality and are spreading the result fast across the globe – a process which is mediated by what has come to be known today as the social media. Big Money married big data a while back, making life outside of the world wide web quite impossible. Today, companies which operate our contemporary forms of media are busy mapping the collected personal data, however contradictory they are, to recreate a single digital twin for each individual within an infinite number of relations to other individuals but also to objects and events (real and virtual). Subject to what is known today as the social graph, humans and machines can be persuaded to engage the world in a particular way, epistemically and cognitively, as well as politically and commercially. These operations, often promoted positively by media corporation as generosity and “sharing”, have been corrosive to the individual psyche and the social body, as the users multiply themselves into micro subjectivities in different contexts, which are often at odds with each other.

Today, the swarm-like movement of ideas and opinions, declarations and condemnations, as well as pledges and disavowals has rapidly turned the Internet into a place where a megachurch meets a 24/7 reality television program. Facebook’s and Twitter’s dark democracy diagonally connects people from the top echelons of all professional fields, particularly those in pop culture, arts, and humanities to the lowest layers of the social field based on the issue or the controversy de jour. What we have come to know as bubbles are a new mechanism of ethical and political value formation and dissemination with a huge difference compared to the previous paradigm of televisual networks. If in the television age, the media was responsible for familiarizing the rising global population with modernization and a unified code of semiotics, today the social media function asymmetrically in the opposite direction; it reinforces the resulting cultural and political outcomes of the post-war modernity through signal refraction. We have moved from preaching to those who are potentially converting to something new to performatively preaching, what is called virtue signaling, to the already converted as a form of day-to-day ideological maintenance. Under the short circuits created by the rapid and accumulative movement of information, preaching to the converted, which was originally meant as a metaphor for ineffective persuasion, is actually having measurable effects, but maybe not the effect that we were hoping it might have. The effect thus far has been the buildup of tension, pressure and adversary contributing amongst groups and individuals and a massive downgrading of the quality of political and ethical discourses. Paradoxically, while the accelerating intensity of emotions, particularly outrage on the social media, is necessitated by the effectual numbing of both the sender and receiver as a result of data oversaturation, this intensity nevertheless produces a particular passive-aggressive psyche which is very new to modern life. We can call this new mode of being in one’s skin “sensitive insensitivity” in which subjects can remain insensitive internally while performing hypersensitivity externally, simultaneously going through with these two opposite ways of experiencing their affection.

As a critic who is often looking for the intentional traces of humans in cultural processes that to most scholars in the humanities seem emergent and organic, I would like to propose that the augmented and virtual insanity we are experiencing as a result of viral media has impacted both the political Left and the Right in different ways. While the right-wing virtual short-circuit was taking place throughout the last ten years and under the radar of mainstream media, the Left only kickstarted its own version of memefied politics not long ago and mostly as a response to the rise of white nationalism, Brexit and the election of Trump. Sadly, in this game, the Right has been way ahead of the leftist curve. In the United States, the deplorable elements who were especially freaked out about the re-election of Obama in 2012, began their delusional regrouping a year later around conspiracy theories and racist mythologies of the birthers, denying Obama’s American place of birth. This regrouping became even stronger after the Gamergate controversy in 2014, in which feminist videogamer Brianna Wu and video game critics Anita Sarkeesian came under fire for an alleged issue of “fairness in the video game industry.[2] The controversy actually resulted into widespread harassment of the involved women for days, highlighting for the first time in a clear way how reactionary, misogynistic and homophobic ideas can take root and culminate not only among video game journalists and fans, but also among a larger general audience. Meanwhile, in Europe, the wrongheaded foreign policy of governments in fomenting civil war in Libya and Syria resulted in another delusional regrouping of the right wing under their opposition to Islam, migrants and refugees. This Avant-right was able to weaponize the social media in original ways, capturing the hearts and minds of a large number of “average folks” belonging to the demographic majorities in European and North American countries, and gaining traction and ultimately helping far right and conservative parties win elections across the globe.

The common denominator of right-wing social media activism is its ability to step outside of the objectivity paradigm and forge a new truth – what in anthropology belongs to the realm of mythology. But modern political mythmaking also has some precedent amongst the Left. For example, Luther Blissett, a collective nom de plume which was active mostly in Italy during the second half of the 1990s, fought corporate news by creating other deliberately fake events and news, in order to generate a moral panic around issues which, although were coherent with the dominant weltanschauung of the official media, were nevertheless completely made up of false information.[3] An example of these practices was a fake exhibition at the 48th Venice Biennale in 1999, during the NATO bombing of Serbia. Eva and Franco Mattes, members of Luther Blissett invented a nonexistent artist called Darko Maver who was supposedly honored in the Biennale. The false story was that Maver had created models of various victims in order to obtain media attention and expose the brutality of war in the Balkans to the world. The truth was that the documentation of his alleged artworks were ordinary photographs of real-life atrocities from the Serbian war which the couple had found on rotten.com.

This operation, as they called it, was a form of mythopoesis, playing with the existing mythic structures of both culture and media, not through negation or critique, but by using ambiguity and anonymity to deform their ideological intents. It is important to remember that these strategies were made possible both by primitive internet technologies and by the naivety of the mainstream media in dealing with a still very opaque source of information. This timeliness is also at work within our current media paradigm because as the social media becomes more and more the vehicle mainstream of news and information, our ability to use it creatively is significantly diminished.

Fast forward to our contemporary moment, after a decade of only addressing the perils of communication technologies and the internet and being quite late in joining the memes madhouse, the Left’s intense activism in the cyberspace came very late, if not also forced by the electoral and cultural victories of the Right. Unfortunately, by this time, the geopolitical borders of the social media were already drawn in hard lines, with huge territories policed and defended by the alt-right trolls.

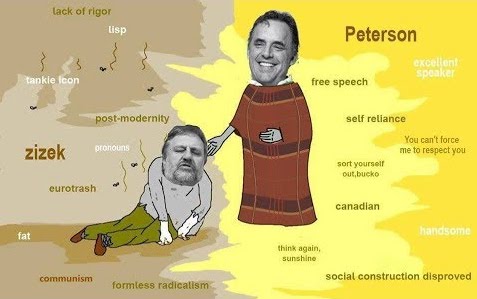

But being early to social media-based mythmaking game is not the only advantage that the right-wing online activists enjoy. While the Left enters the memepolitics mostly to defend its seemingly shrinking turf and not to expand its base, the Right has steadily been conquering more territory and converting middle of the road liberals towards its cause. The viral dissemination of Jordan Peterson’s ideas, the right-wing Canadian clinical psychologist, and his success in impressing some reasonable people, is a perfect example of how the Right still has the advantage in this area of political competition. Using the same example, the Left has mostly been responding to Peterson’s gross generalizations of leftist subjects such as Marxism, Postmodernism, feminism with outrage. At the heart of the leftist waves of online rage is an attempt to hold on to the already made social justice progression –, which at some point in the past were expressed as utopian demands, but by now are more or less accepted liberal norms, even enforced by most neoliberal institutions of power. From the position of the Left, these values need to be vigorously defended from the right-wing onslaught at any price. But are we sure that they are doing anything more than producing creating sensitive insensitivity?

The lack of an imagined forward-looking utopian project and the tendency to defend established norms also means an inability to engage in mythopoesis. Today, the leftist online myths are only effective on like-minded Internet users and are mostly negative, expressing the perils of things that have already taken place, like racial and sexual violence or transphobia, and they mostly amount to a demand for further restrictions on speech in the hope of maintaining the existing norms within the leftist bubble. This is why the no-platforming policy of the Left should have instead been called not-in-my-secluded-bubble.

It should be obvious at this point what kind of counter-strategies are needed by the Left in order to overcome its insecurities and deficits in the meme wars of the mad mad world of technopolitics. The Left needs to break out of its cyber bubble and start to develop more effective campaigns to win the hearts and minds of those who are not already in its milieu. Left has to learn to stretch the borders of truth, produce semi-real heroes and stop apologizing for small mistakes. Instead of having a purely negative, resented and hysterical representation of the right-wing’s activities, it must engage and use effective viral strategies to disrupt its adversaries from the inside: this is what is missing that should become the basis of the ‘Mythopoesis of the Left’ before the social media as a medium of contingency is further reified, regulated and nurtured into an official form of mainstream media.

[1]. André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993).

[2]. For a decent QA about the controversy please visit: http://gawker.com/what-is-gamergate-and-why-an-explainer-for-non-geeks-1642909080.

[3]. Marco Deseriis, “Lots of Money Because I am Many: The Luther Blissett Project and the Multiple-Use Name Strategy” inThamyris/Intersecting No. 21 (2010) 65–94.