A large body of classical Persian visual art of the last millennium consists of illuminated manuscripts. These paintings on paper have often been compared to the similar tradition of Byzantine miniatures and therefore referred to as “Persian miniatures.” André Godard and Basil Gray, two prominent scholars who studied Persian art in the early 20th century, believed that miniatures developed through the influence of paintings from both the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties and, through an evolutionary course mainly taking place in Persia, became a distinct form in the 13th century. These scholars have argued that Chinese painters who were brought to Iran in the 13th century to paint in the royal courts of the Mongol and Timurid empires were responsible for the initial development of the style. On the other hand, Persian miniatures were the dominant influence on other Islamic painting traditions, principally the Ottoman miniatures in Turkey and the miniature tradition in the Indian subcontinent. Accordingly, Persian painters initiated several schools of paintings and opened the path to what later, between the 15th and 16th centuries, transformed into a truly Persian phenomenon. [1]

The themes and motifs of Persian miniatures are mostly related to ancient Persian mythologies and Islamic doctrines, as well as the allegorical and symbolic imagery that is also referenced in a host of more common cultural products ranging from Persian classical poetry to Persian rug designs. To achieve their effect, painters used geometry and a vivid palette, incorporating margin patterns and text according to the requirements of their final presentation in the box or book format. Persian miniatures are also known for their compositional qualities, particularly the way in which a closed crop interior consisting of detailed ornamentations juxtaposes a distant landscape. Regardless of their thematic content, they share with early modern paintings a keen interest in the notions of flatness and spatial ambiguity (fig. 1, 2).[2]

Figure 1 & 2. Left: Sung Dynasty painting, Right: Persian Book Art

The word ‘miniature’ is derived from the words ‘minimal’ and ‘nature’, and, being a relative term, only makes sense if used to refer to small book paintings and illustrations within a wider painting tradition that also includes landscape paintings in larger formats. Persian paintings, unlike their Chinese counterparts, rarely focus on nature as their primary subject. Given the exclusivity of religious and philosophical book art as the form through which Persian paintings were circulated and collected, renaming this art ‘miniature’, consciously or not, has diminished the social function of the art and has consequently severed it from its historical roots as collectable traveling objects, a tradition that is thought to have begun in the 2nd century CE with Manicheans.

The relationship between Persian illustrated manuscripts to Mani and Manichaeism has failed to appear even in the footnotes of Western writing on Persian miniatures as a possible reference. Throughout the last hundred years, only a single Western art historian, Thomas W. Arnold, has raised the possibility that Manichaean bookmaking and painting traditions might have been the source for the Persian paintings of the Safavid Era. Rejecting the possibility of Christian influence on the existence of angels and clouds in Persian paintings of the 12th century, he added that:

“The only other religious art that could have produced these pictures was the Manichaean, the Eastern Character of the types of face and figure, and the similarity in technical details to the Manichaean paintings that have survived in Central Asia, suggest that this is the source to which these strange pictures must be traced back.”[3]

This reading of Persian paintings remains marginal throughout the twentieth century, and only recently Suzanna Gulacsi has invoked it by referring to Arnold’s statement, in which he argues “that trends developed by Sassanian and Manichaean painting survived in Persian medieval art.”[4]

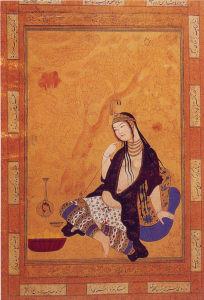

Consider the case of Kamaloddin Bihzad, the most historically significant painter from 15th century Persia (fig. 3).[5] The Afghan historian Albdulkarim Khondamir, writing in the 15th century, refers to him as the originator of novel designs and rare art forms: “[Bihzad’s] Mani-like brushwork overwhelmed all other painters.”[6] Available information on Mani’s paintings suggests it was impossible for Khondamir to have seen Mani’s art. Mani’s original paintings are believed to have been illustrations for a condensed version of his teachings, named Ardhang or Arzhang (a Middle Persian synonym for the Greek word Eikon, meaning ‘image’) which historians agree have been lost. To understand what could have compelled Khondamir to connect a 15th century painter to a second-century prophet we must turn to Mani and Manichaeism for a possible answer.

Figure 3. Bihzad painting, 15th Century

Manichaeism

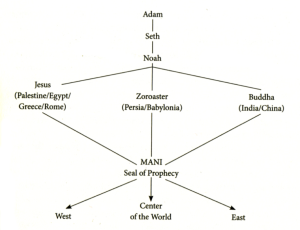

Through the translation of Manichaean codices found in Central China and Egypt, archaeologists have come to believe that Mani was born and raised in the small Elchasai Christian community in pre-Islamic Persia around the turn of the 3rd century, at the time of the Sassanid empire.[7] In Manichaean hagiography and other historical documents, in addition to Christian knowledge, it appears likely that Mani would have had access to several other sources of cosmological knowledge derived from Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Greek mythology, all of which had exerted a strong influence on the Mesopotamian (fig. 4).[8]

Figure 4. Mani’s own position in relation to pre-existing religions, Tardieu, 17.

By combining these influences, Mani is thought to have designed a comprehensive system of beliefs and the associated rituals that could gradually bring an end to the suffering of the world by liberating, particle by particle, the trapped forces of good and light from the materiality of evil and darkness. In Mani’s dualistic system, matter represented darkness and light represented the immaterial forces of the divine spirit, hence the reference in the English language to Manichaean as a dualistic approach to any subject.

A virtuoso artist in his own right whose primary miracle is known among Iranians as the aforementioned lost illustrated book called Arzhang, Mani doctrinally placed the arts, including painting, calligraphy, and music in the category of the divine spirit, equating the act of making art with god’s creation of living forms, making the experiencing of art superior to conducting an ordinary life in the material world. As to the relationship between Mani and painting, recent scholars believe that Mani could be among the first artists to have formulated a cohesive metaphysical theory of art and a practical mechanism for its systemic propagation and distribution.[9]

Mani died a martyr on the order of Bahram I, the Persian emperor, under pressure by Zoroastrian priests who saw his heterogeneous cosmology as a threat to their homogenous religion that was based solely on Persian ethnic mythology. However, the persecution of Manicheans did not end with Mani’s death. It is important to remember that the later disappearance of Manichaeism in the Christian West and the Islamic East through denunciation, expulsion and mass murder was the spearhead of religious intolerance. Manicheans were the only believers in Jesus Christ to be executed both by order of the Roman Church and decrees issued by Islamic rulers in Baghdad. The withering away of Manichaeism can be seen as a symptom of the growth of new, more exclusive, and more localized societies, those that foreshadowed the Middle Ages. [10] Meanwhile, it is also important to keep in mind that, contrary to the intolerance in Europe and West Asia, Buddhist central Asia was more or less the only refuge left to Manicheans, a place where they could set up temples and monasteries, living peacefully in places like Turfan in China. In the last decade of the 19th century and in the first decade of the 20th century, German scholars discovered antiquities belonging to Manichaean monasteries in Turfan and Dunhuang, China, that included book art and scrolls written in Middle Persian, Turkish and Chinese that shed light on a disappeared culture and religion. These discoveries—along with another in the late 1920s in Medinet Madi, Egypt by another group of mostly German scholars, whose role in collecting these discoveries also caused the loss of some of this material during the bombings of Berlin in the Second World War—advanced the knowledge of Manichaeism.

It is through observing the remains of Manichaeism in Turfan, China that one can come to an understanding of the Manichaean culture and study its relationship to Persian miniatures and the larger field of Chinese and Mongol Painting. The translation and publication of a commentary on Arzhang found in Turfan, called Ardhang Wifri, speaks of Mani’s paintings in relation to his teachings, thus substantiating the existence of such a book in the past.[11] Yet, since no originals or copies of Mani’s book are known to have survived, for a visual assessment of Mani’s style we shall turn to the remains of Manichaean book art to identify which set of fragments could potentially resemble Mani’s original style. [12]

In addition to sharing elements with Chinese and Indian art, the Manichaean fragments found in Turfan possess a distinctly Persian look that connects them to what is known about Persian art and other Mesopotamian influences from the 3rd to 6th centuries, before the arrival of Islam.[13] The antiquities from the Sassanid period exhibit certain qualities, such as the quality of the line, the simplicity with which the faces are painted, and the unnecessary detailing of the folds in the garments.

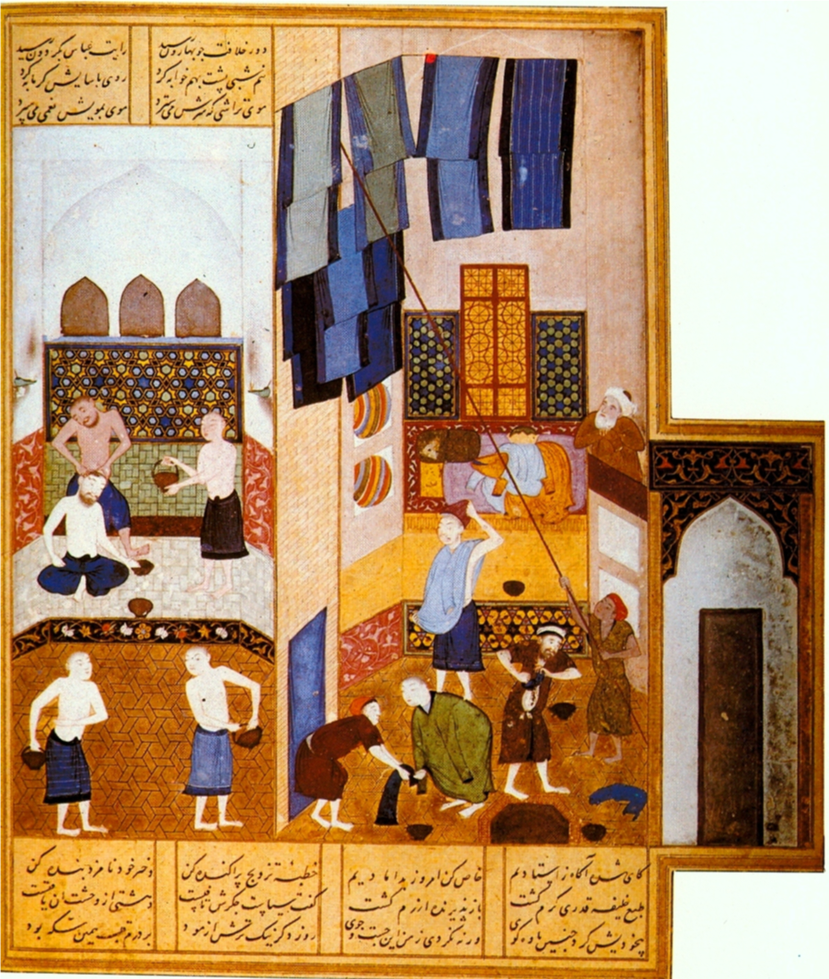

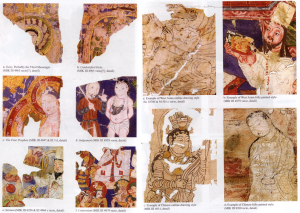

In her codicological study of Iranian illuminated book fragments, Zsuzsanna Gulacsi identified the Manichaean themes, subject matters, and styles, and compared them to what could be seen as the influence of the local Chinese setting on the manuscripts. She describes ‘codicology’ as the study of the codex as a whole, not just a document containing separate pictorial and textual elements (fig. 5). Rather than studying a book in a cultural vacuum, a codicologist approaches his/her subject as a cultural product, every element of which can shed light on its purpose and meaning.[14] It is with the aid of such a methodology, such as paying attention to the decorations, the leatherworks on the cover, and other details such as the layout and placement of stories, that Gulacsi can divide the paintings in the book into the two distinct categories.[15]

Figure 5. Example of illustrations describing a codicological study of images alongside the text and the layout of a manuscript.

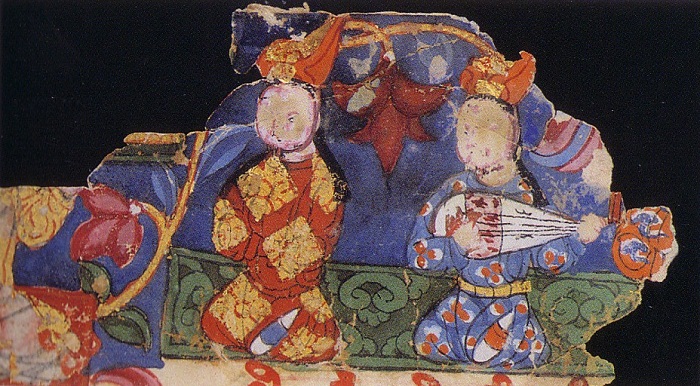

The first group depicts scenes containing not only local dignitaries performing Central Asian customs, but also includes representational elements like lotus flowers and other plants that belong to the local setting. In contrast, the second group of paintings, those that concern our study, contain paintings that illuminate Manichaean theological and doctrinal subjects(fig. 6).[16] Based on the distinct characteristics of this second set of fragments—i.e. iconography, brush style, and the use of colors—she concludes that they are derived from pre-Turfan Manichaean book art, which continued traditions going back to Mani’s own painting and scribing styles. Many such scenes must have originated in Mani’s Arzhang and have been reproduced by later generations of Manicheans.[17]

Figure 6. Turfan fragments depicting two different sets of stylistic themes and subject matters: Manichaean {bottom right and top left} and local Buddhist {rest}

Figure 6. Turfan fragments depicting two different sets of stylistic themes and subject matters: Manichaean {bottom right and top left} and local Buddhist {rest}

The Chinese and Mongolian Connections

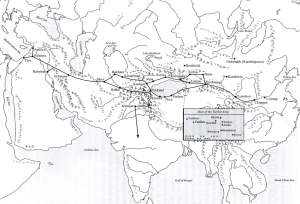

In order to understand the origins of styles identified in the Turfan antiquities and to link Mani’s painting tradition to Persian paintings from the 15th and 16th centuries, consider the history of Manichaeism along the Silk Road(fig. 7). Through a missionary program run by Mani and his disciples, his Religion of Light spread widely, first in Mesopotamia and later across frontiers into the Roman Empire, to Northern India, and into Central Asia. To assure the accurate transmission of Mani’s doctrines, scribes and illustrators accompanied the Manichaean missionaries. These efforts echoed the faith’s philosophy and its emphasis on painting and scribing practices, especially after Mani’s death at the hands of the Persian Emperor, Bahram I.[18]

Figure 7. Manichaean Spread along the Silk Road

In his book, Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China, Samuel Lieu documents the spread of Manichaeism eastward from Persia towards Transoxiana in Mani’s lifetime and the missionary work that followed his death. Historical sources confirm that Mani himself converted both the ruler, named Peroz, of Persia’s eastern province and Transoxania’s ruler, Turan Shah, around 240 CE, helping to set up monasteries for the propagation and practice of Manichean religion and art.[19] By the time of the Muslim conquest of Central Asia in the 7th century, Manichaeism had extended its influence over a vast area and was impressively organized into monasteries and assemblies all the way to the borders of Eastern China.

Before the conversion of Uyghur rulers in the 11th century to Manichaeism, Sogdian traders not only provided the faith with financial support for its evangelical projects but also helped to physically spread the word through the arts and books they took across the Silk Road.[20] Active as transnational traders since the 1st century CE, Sogdian merchants were the most important agents of the silk trade and had connections from the Roman Empire all the way to China. Because of their connections on both sides of Transoxania, the Sogdians—who were centered in the city of Samarkand, the second-largest city in Uzbekistan and capital of Samarkand Province—were the ideal middlemen for exchanging Chinese silk from the East for goods from the West that China needed, such as a strong breed of stallions named “blood horses” in China.[21]

The influence of Manichaeism on Buddhism can be explained in two ways, the first of which is to highlight the relationship between the Persians, particularly the Manichean Sogdians, with the Chinese. The relationship between China and Persia goes back to when China was reunited, at first under the Sui and then under the T’ang dynasty, after several centuries of divided rule.[22] With the Islamic crescent looming large on the western horizon, the rulers of Persia and Transoxania turned to China for military assistance against the forces of Islam. The Sogdians were the principal beneficiaries of this upsurge in trade and diplomatic contact between China and Persia. As new trade routes veered north after the old ones were closed due to wars, Samarkand became the boom-town of Transoxania. In these trades, Manichaean priests probably played more than a spiritual role in mercantile society. Those of a junior rank undertook scribal artistic and musical duties, as depicted in some Manichaean paintings. They would have performed the roles of painter, musician and entertainer.[23]

During the period of eastward expansion, Manichaeism both assimilated many features of the Buddhist religion and at the same time exerted influences on it such as the concept of light and dark.[24] According to Chinese Manichaean texts, Empress Wu Zetian of the Tang dynasty showed pleasure in what Mihr-Ormuzd, a Manichaean priest, had to tell her about his religion. Apparently, she was continuously looking for other faiths that, unlike Confucian beliefs that did not allow women to occupy the role of emperor, would sanction her rule.[25] Unlike Zoroastrians and Christians in the middle kingdom, Manicheans could look forward to a long life in China and were able to achieve this permanent status by emulating Buddhists as a strategy of survival. What allowed Manichaeism relative tolerance in China was that, compared to more local ancestral religions such as Taoism and Confucianism, Buddhism itself was an imported religion and could not therefore really characterize Manichaeism as an intrusion by outsiders. This intertwined relationship guaranteed a certain level of mixing between Buddhist and Manichaean ideas.[26] Mani started to be referred to in China as the Buddha of Light and Manichaean illustrated manuscripts began to penetrate the courts of princes.[27] A comparison between two different versions of a Manichaean text, one found in Turfan and one found in a Chinese translation, the Parthian original, can show us the level of similarity and difference between Persian Manichaeism and the Chinese version of the Buddhist faith:

Parthian

Their verdant garlands never fade;

they are weathered brightly, in numberless colors.Chinese

Floral crowns are verdant, wonderful, dignified and solemn,

Shining on each other with great vitality, and never fade or fall;

Whilst my carnal tongue wishes to praise, my faculty of thought fails me:

Immeasurable are the wonderful colours, which never fade or diminish.[28]

The second way to explain the influence of Manichaeism on Buddhism is by looking at the remarkable conversion of the Uyghur people to Manichaeism, a conversion that provided Manichaeism with the practical means for historical survival and a way to continue their traditions.[29] A Turkish ethnic group with direct ethnic and cultural links to Prehistoric Persia since 1000 BCE, Uyghur tribesmen eventually formed the Uyghur Steppe Empire in the 8th century and even though the conversion of their ruler Bogo Khan to Manichaeism was a personal affair, it had a positive impact on the spread of the religion in central Asia and Manichaeism advanced under these favorable conditions.[30]

Even after the demise of the first Uyghur empire, Manichaeism remained the official religion of the second Uyghur empire, established in Tarim Basim in the 11th century, with its capital city in Coco. It was customary at this time for three or four hundred Manichaean priests to gather in the house of a prince to recite the books of Mani and invoke blessings on the ruler. Free from persecution and supported by royal patronage, Manichaean communities in the Uyghur kingdom became flourishing centers, not only of artistic and economic activity but also for the propagation of Mani’s ideas. It was from the ruins of these centers that most of the Turfan remains were found.[31]

In the early 13th century, during the reign of Genghis Khan, Mongols conquered Persia. Mongol control was reinforced about a hundred years afterward by Timurid conquest in the mid 14th century. Meanwhile, China itself was conquered by Mongols in the late 13th century when Kublai Khan establishing the Yuan Dynasty. With the establishment of this Buddhist dynasty, Kublai Khan shifted the Capital back to Beijing, where merchants, traders and administrators converged to offer their services. Most of the many foreigners at the Yuan court were Persians or Persian speaking merchants and administrators (fig. 8). The Yuan Dynasty had connections with the Uyghur region through trade with Sogdians merchants, who, before the conversion of Uyghur rulers, were instrumental in financing the Manichean monasteries and had extensive relationships with both Uyghur rulers in Central China and the Yuan Dynasty emperors in Mainland via The Silk Road.[32]

Figure 8. Persians in China, Yuan Dynasty painting, 13th-14th century, colour on silk

Christie’s Nov. ‘88 catalogue, Lot. 12

The illustrations for the Persian Epic poem, Shahnameh (fig. 9), or the Book of Kings, one of the most frequently illustrated books in 15th century Persia, is a case in point for establishing a link between Manichaeism and Persian painting. Written in the 10th century by Ferdowsi, a towering figure in Persian mediaeval poetry, the book, known among Iranians as a mythical history of the world that concludes with the Arab conquest of Iran, mainly contains centuries-old stories from Sogdian mythology.[33] Written as one large poem, perhaps the longest poem ever written in Persian, Shahnameh depicts the history of the world from its inception. Covering the history of the Persian Empire from the Achaemenid (550–330 BCE) onward, in a mythical framework, the stories of Shahnameh not only parallel the history of Manichaeism moving eastward with the development of Persian history, but also begin to include mythical figures from the Sogdian and Uyghur people, who share both an ethnic and cultural heritage with the Persians, dating back to 1000 BCE.[34] With the conquest of Persia, the Mongol and Uyghur rulers of Central Asia started to pay special attention to the book and ordered its illustration many times over the 12th and the 16th centuries.[35] Whether depicted on tiles as both written text and pictures in the 13th century for Mongol rulers of Persia in Eastern Iran, or illustrated numerously in manuscripts now kept in various museums throughout the world, Shahnameh is a cultural bridge that brings both the Sogdian, and perhaps Manichaean, roots of Persian culture back to Persia. In various versions of this book, one can find Manichaean influences, side by side with Mongol, Uyghur, and Sogdian influences, informing what would later become—in the 16th century, during the Safavid dynasty—classical Persian painting.

Figure 9. Illustrated Shahnameh, early 14th century, Washington DC, Freer Gallery of Art

Scholars like Grey were previously quoted as saying that the style of Persian painting had been influenced by Chinese paintings through the Mongolian invasion. Therefore it is possible to suggest that the Mongol invasion of Persia in the 13th century by Central Asian tribesmen, rather than exclusively bringing a Mongolian or Chinese influence to Persia, must have reintegrated the lost or forgotten elements of Manichaean art into Persian visual culture. Even though further research is necessary to validate the influence of Manichaeism on Chinese and Mongolian painting traditions, it is safe to suggest that Manichaeism exerted influences on both Chinese and Mongolian cultures. It is likely that the book artists in Persia recognized something similar in Eastern cultures and imagery that encouraged them to embrace Buddhist aesthetics, not as a foreign and exported entity, but as a strange yet familiar one.

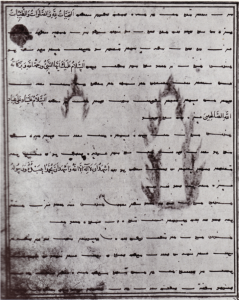

One area that shows potential for researching the links between Manichaean culture and Persia is the study of Uyghur/Farsi coins made by the Mongols for use in Persia. These coins often included both the local Farsi Arabic script against the Manichaean Uyghur script on their reverse side (fig. 10). There is also the issue of the Uyghur influence on Persian illuminated manuscripts and paintings, documented through the relevance of the Uyghur script to Persian and Arabic scripts (fig. 11). Arabic scholars believe that the Kufi alphabet, one of the earliest documented Arabic scripts, was directly influenced by the Syriac script that was used around the first century in northern Mesopotamia.[36]

Figure 10, Mongolian issued coins, Persia, 13th century, minted in Tabriz 3.8 g

Figure 11, Uyghur script, used alongside Arabic Naksh script By Malik Bakhshi, Herat, 840 AD, Bibliothéque National, Paris

The Uyghur rulers adopted the Uyghur/Manichaean script, an innovative and modified version of the Syriac script, in the 8th century for scribing the official documents and religious manuscripts of Manicheans and Buddhists. Modeled on the Sogdian cursive (italic) alphabet, the Uyghur script is documented in the “Penitential prayer of the Manicheans”, a manuscript that was discovered in Turfan.[37] On the other hand, the Persian Nastaaligh script, used alongside the illuminations in Persian book art in the 15th century, is known to have evolved through the modification of both the Kufi and Uyghur scripts. It could also be possible that Manichaean painting influences reentered Persian culture alongside the Uyghur script from Central Asia.

Then again, there is the possibility that the Manichaean influence never really left Persia and remained latent in different art and craft forms between the arrival of Islam and the conquest of Persia by Mongol and Timurid empires, its characteristics later becoming reinforced by the integration of Uyghur/Mongol styles into Persian painting (fig. 12, 13). First explored by Thomas Arnold, this possibility has never been seriously explored by scholars and researchers. While a visual comparison of a Manichaean illuminated manuscript and Persian book art may not constitute a conclusive argument, in the end, it could seal the issue by demonstrating how Manichaean cultural influence has been the means of aesthetic survival for a truly ancient Persian culture that flourished throughout the documented history of Persia, since the 2nd century CE.

Figure 12 & 13. Left: Persian Book Art, Tabriz, 1425 AD,

Right: Manichaean Restored Painting Fragment, 800 AD, Turfan

[1] André Godard. The Art of Iran, Berkley: University of California, 1962, 28-32

see also: Basil Gray, André Godard. Iran: Miniatures Persanes, Bibliothèque, impériale, Volume 6 of Collection Unesco de l’art mondial, Unesco, New York Graphic Society, 1956 2-5

[2] Mullarkey, John. The New Bergson, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1999, 190

[3]Thomas W. Arnold, Survivals of Sasanian and Manichaean Art in Persian painting, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924, 23-24.

[4] Zsuzsanna Gulacsi, Mediaeval Manichaean Book Art, Boston: Brill, 2005. 6.

[5] Sheila Canby, Shah ‘Abbas, the remaking of Iran, London: British Museum Press, 200, 123, 178-179.

[6] Abolala Soudavar, Art of the Persian Courts, New York: Rizzoli, 1992, 95.

[7] Michel Tardieu, Manichaeism, translated from French by M. B. Debevoise, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008, 1-8. Documentation regarding Manichaeism has grown considerably over the past few decades. Information regarding Mani’s life comes from a comparative study of Coptic sources in the collection of Kephalaia of Dublin published by S. Giverson, Cahiers d’orientalisme 14, 1986. In the Iranian domain, the Turfan fragments conserved in Berlin have been published, translated and annotated by W. Sundermann in Berliner Turfan-texte, 4, 1973, have been crucial in establishing a proximate biography for Mani. The details discussed in my paper have been corroborated by both the Persian-Arabic sources particularly the collection edited by A. Afshar-e Shirazi, Motun-e arabi va farsi dar bare-ye Mani va manaviyyat “Persian and Arabic Texts on Mani and Manichaeism.” Tehran, 1956, as well as Chinese documentation with German translations, assembled in H. Scmidt-Glintzer, Chinesische Manichaica, Weisbaden: Harrossowitz, 1987.

[8] Jess P. Asmussen, Manichaean Literature: Representative Texts Chiefly from Middle Persian and Parthian Writings, New York: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1975. 26-57.

[9] Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Manichaean Art And Calligraphy, New York: Brill, 1982, 60.

[10]Peter Brown, “The Diffusion of Manichaeism in the Roman Empire.”

The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 59, No. 1/2 (1969): 92-103.

[11] Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, “On the Nature of Manichaean Art.” Studies in Manichaean literature, and art edited by Manfred Heuser, Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Leiden: Brill, (1998) 281.

[12] Klimkeit, 277.

[13] Gulacsi, 7.

[14] Gulacsi, 8.

[15] Gulacsi, 22-25, 42-48.

[16] Gulacsi, 218.

[17] Gulacsi, 219.

[18] Tardieu, 35.

[19] Samuel N.C. Lieu, Manichaeism in the later Roman Empire and medieval China: A Historical Survey, New York: E.J. Brill, 1994, 154.

[20] Lieu, 179.

[21] Lieu, 220.

[22] Lieu, 227.

[23] Lieu, 227-230.

[24] Lieu, 215-216.

[25] Lieu, 189.

[26] Lieu, 190.

[27] Lieu, 192.

[28] Lieu, 205

[29] Gulacsi, “Identifying Corpus of Manichaean Art Among the Turfan Remains,” 192.

[30] Lieu, 193.

[31] Lieu, 199.

[32] Soudavar, 30.

[33] Eleanor Sims, Marshak Sims, Boris I. Grube and Ernst Grube, Peerless Images, Persian Painting and It’s Sources, London: Yale University press, 2002, 12.

[34] Sims, 32.

[35] Sims, 32-47.

[36] Basil Gray, The Arts of the Book in Central Asia, 14th~16th Centuries, New York: UNESCO, 1979, 7-14.

[37] Gulacsi, 196.