“It was in the scenario of the dream that we first received, as children, the lesson that things can be other than how they manifest”

Vicente Ferreira da Silva

“These dreams, it is necessary to inhabit them in order to convince ourselves they were ours”

Gaston Bachelard

“Dreams burn / but in ashes are gold”

24-25, Kings of Convenience

1. From There to Here

Studio Ghibli’s films seem to provide a new mode of existence for Color, or for the art of painting. Not only because they recover the aesthetic plasticity of color – that playful, variegated saturation we last encountered in comic books –, but because they recover, in their own way (that is, without filing away the flaws of translation), how a painting was viewed before the age of technical reproducibility (say, by a Renaissance-era spectator). They thus recover the very condition of aesthetic contemplation prior to the institutionalization of the art system in the West, that catharsis of the artistic experience with largely Romantic roots and clear Eastern correlates. They sculpt, with the matter of Western aesthetics, based on flexional linguistic communications in a chained logical flow, certain Eastern feelings that are unapproachable by this aesthetics, because they are based on isolating moral and sentimental communications via intuitive mosaics (1). More than that: by accomplishing such an East-West transposition, Studio Ghibli’s animations also recover a certain admiration – characteristic of painting, in the West – for the incommunicable, for the inexpressible, for the apperceptive absorption of a signifying form (2), for the dream that does not intend to come true.

Vilém Flusser wrote that a dream that comes true is a frustrated dream, since reality never makes the dreamed content something so free, so enchanted and hypnotic, as imagination did in its deep projections (3). Reality never lives up to the expectation that is the very substance of a dream (which, in turn, is only defined as a dream because it is in this way superabundant). Ernst Bloch traced a long systematization of an ontologically considered utopian principle based on, among other things, this very suspicion that dreams are firmer, clearer, and more powerful than their realization (4). For the dream that never comes true is a pure dream that does not grow old, it is the dream’s in its eerie, originary nature. Thus, the dream of flying is destroyed by the flight of the airplane, which, far from instantiating the dreamed content in material reality, decalcifies it (5). The dream of flying becomes a logical impossibility in a world where one already flies (one can only, now, propose alternatives to the confined “flying” of the airplane, but only from technicality to technicality, from bureaucracy to bureaucracy, without that imaginative amplitude provided by the implausible). In short, then, a dream realized is one less dream to dream.

A series of affective feelings derive from this same eidetic scheme in which the knot of making is also the knot of unmaking: erotic desire, religious devotion, homesickness. In the arts of time, such as music and dance, the threshold between realization and non-realization is a central axis, since these phenomena are only perceived in their evanescence (6). The smell of a perfume always escapes us – let’s think of Proust and his madeleines (7). Love is only experienced as absence or as archive – remember Sappho and her dismemberments (8). Philosophy itself, as the eroticism of thought, seems to correspond to this attempt of capturing the disappearance of an idea right in the center of its estuary, since its point of springing is also its point of departing. Whenever an idea becomes systematized, its essence, the very thing it sought to systematize, silently escapes from the theoretical edifice (9). In a poem by Borges, a cartographer tries to keep the entire universe in a book; when he is satisfied and finishes the herculean task, he raises his eyes to the skies and notices that he had forgotten the moon (10).

In the case of Western painting, one can say that it starts from approximation as a motive for unattainability: to be inside what has been painted is impossible, but we only feel the aesthetic pleasure of painting if we make it the driving force of a reverie of inhabitation. This attempt to transmit a mimesis of yourself or of life itself, and to draw a certain “vital import” from the autonomous resemblances it finds, is very much a Western habit (11). The idea that underlies this pairing gesture is that the reverie of being-there or being-in-the-world (propitiated by the virtual transparency of the image, for example) is the closest we come to realizing the dream as an unrealizable dream (12). If we cannot enter the image of painting or of film, it is precisely because this would destroy the dream of doing so, and therefore deny the apotheosis toward which the image is intended. This is the moral of films like Straub and Huillet’s A Visit to the Louvre (2004) and Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery (2014), by the way: to stroll through the museum unpretentiously, to see and analyze it without wanting to extract meaning, but only to enjoy the wandering, is a way of not getting frustrated with the impossibility of “realizing” painting (that is, implanting it as the manifested real).

A frame from A Visit to the Louvre ( 2004).

With Studio Ghibli, films become paintings in motion, that is, they become landscapes that one can only dream of, unrealizable landscapes. The exploration of fantastic environments, beings, relationships and signs also contributes to this effect. Of course, the method of assembling – dissociating and then reconnecting – factual things (animals and plants, bits of biomes, technologies, narratives) to compose fantastic things with them is more than escapism, since it says something about these factual things, about their structures and their astonishments. In fact, even the most distant utopia is not alien to the world but extends and surpasses it, “it wants to see far away, but, deep down, only to cross the darkness that is very close to this living instant” (13). This is how the food in these animations, as with the pineapple in Only Yesterday (1991) and the lamen in Ponyo (2010), acquires a magical aura, of inventive fascination, where gastronomy is a kind of magic, an alchemical transformation of something into more-than-something. It is by the very appearance of the world that, in these films, the world becomes another, which does not belong to us, and which we can only watch in ecstasy because we cannot visit or know it in depth, we cannot suck it up to satisfy our will. It is an eternal dream without contact, without channel, without openness.

The fact that Ghibli’s films utilize a Western technical-normative set to express a certain Eastern experience is not secondary here. Miyazaki creates animated art along the lines of Walt Disney’s films and the fantastic children’s literature and avant-garde comics of Europe, and actively moves away from the aesthetics of anime (which, on the contrary, already seem to achieve a consolidated grammar of cultural conversion, with clear routes for swallowing Western animation and installing in them Eastern cognitive tools). In this sense, Studio Ghibli seems to deliberately express an inability to enunciate the Eastern praxis, always showing it “from the outside”, without integrating the Japanese episteme to its articulation. This creates an oriental art with an occidental facet, whose main Eastern value is the encounter with an extraordinary unknown, and a disquiet at the ontic level (14). This liminal fine-tuning of certain plastic and narrative significations, and their translation across cultures, aggravates the sense of retraction of the in-itself brought about by these films, making them even more dreamlike, as they are properly unattainable, impossible to touch. The encounter is reconfigured into hallucination, an exoticism that is not restricted to Eastern culture but now seems to extend to all non-animate reality.

The famous lamen cooking scene from Ponyo (2010).

The ma, “negative space” or “contemplative emptiness” of Japanese aesthetics (especially the tea ceremony), which Hayao Miyazaki has already pointed out as the defining ethos of his work, just like the concept of iki, the principles of haikai or of Nô and Kabuki theaters (15), also arise from the counterintuitive relation according to which the closer we get to the filmic fabric, the more we seem to move away from it. This withdrawal amidst approaching, veiling amidst unveiling, the dealing with the world that always finds an interval between circumspection and operation, Heidegger tells us, is the original face of dasein (16). The cognitive grasp of exotic worlds in that space of interplay unified by duration, distance in proximity itself, is the distinctive regulative instrument of an authentic presence (17). When a film of classic cinema (of “acted”, live-action cinema) plays with duration, it is also seeking this experience of the hollow (18). In a sense, most films try to fit into a dreamlike situation, something that the film critic notices with ease (19). The main difference is that, in animation, the dream is totalizing, encompassing everything, because it is the very ontology of the painted image not to correspond to reality, to not to be indicative, but to jump freely amidst a certain fluidity.

On the other hand, it is clear that the cinema of Studio Ghibli adapts tricks characteristic of this classic cinema (montage modes, camera positions, and other productive limitations). Suddenly, the perspective shifts into a plongée or an artificial counter-light intensifies itself, as if the scene was being played out in a studio and not at the tip of the animator’s pen. Events of this kind, which in classic cinema would often fill the image with cliché, in these animations express, on the contrary, the consecration of ma. This is why, were they recorded in the flesh, Whispers of the Heart (1995) and From Up on Poppy Hill (2011) could be cheesy romantic comedies and little more than that. Because they are paintings, that is, because they are unattainable and because they propose the intentional search of the cinematic gesture of distancing, the films quickly enter the transcendental register. For then the technique didn’t fall lazily into convention, it didn’t end up there by association with the most comfortable compositional model. It is there deliberately, as if to say: this is what makes cinema cinema. The cliché that has been emptied of cliché is not infrequently a psychagogic ignition of beauty (consider the unexpected truth of such tired metaphors as “sea of roses” and “crack of dawn”) (20).

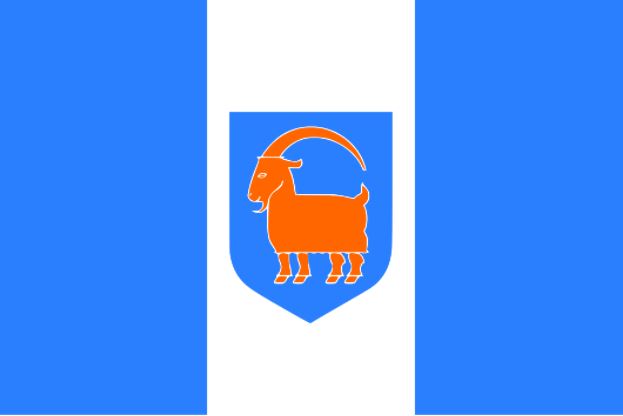

Not for nothing, these films seem to bring us back to childhood, since childhood is precisely the phase in which all catharsis is new, in which no metaphor has lost its freshness, its magnetism in relation to unchartered zones of perception (21). Not for nothing, Ghibli films most enclosed by high fantasy narratives, which depart from a magical realist account for their degree of eccentricity and long-winded representations, such as Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Princess Mononoke (1999), need not prize a very original script, or, indeed, semantic mega-machinations of any kind. See the case of Pom Poko (1994) and The Secret World of Arrietty (2010), which have virtually no personable conflicts and are anchored in the contemplation of simple states of affairs, or justified orders (the microworld and the world of metamorphic textures) that simply unfold and permeate the viewer, so to speak. The best action film is this one in which the narrative structure is not defined by habitual recognition, but, as in a childhood consciousness, allows the story to float between acts – this is the structure of My Neighbor Totoro (1988), for example. In The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), probably the Ghibli film most affixed to a traditional narratological arc (“fall-and-redemption”), it is up to the soundtrack à la Henry Mancini and to the details of fantastic range (forged flags, emblems, small objects) to insert into the actions a dimension of a-functionality.

The flag of the duchy of Cagliostro, from Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979).

The final effect, in any case, is that we watch Studio Ghibli’s cinema with clean eyes, seeing the world clean itself in return. Its films provoke in us a mindful tranquility. This pacification or suspension of the real seems to be the closest a contemporary man (a humanist, secular and bourgeois man) can get to the Stimmung that a Renaissance painting used to invite in its time and until a little bit later on. The experience of painting described by Romantic philosophy, this experience of transcendental absorption, is only possible in the context of a certain experiential innocence about the very category of art (22). But if the museum as an acute experience of painting prevents the neutrality of vision (which is irremediably conditioned by the general circumstance of being in the museum), Studio Ghibli’s moving paintings recover a more authentic experience of Western painting: dreaming while knowing that the dream will never come true – and, in that, loving the dream even more strongly.

2. From Here to There

If we were absolutely technical in our terminology and our mode of conceptual grinding, we would have to admit that there are only two possible human activities, two ways of “spending the day”, from a practical point of view: media and dreams. In the course of a routine, we are either inscribing ourselves into the world, storing a certain unity of action and manipulating it retrospectively by means of an instrumental experience (i.e. we are awake), or else we are caught in the oneiric stream of seemingly random, external images that must constitute the only truly immediate alternate reality environment (i.e. we are asleep). We could challenge the skeptic to name a single human activity that is not mediated (23), against which no intermediary – at least sensorial – is ever imposed, if not the pure delirium of dreaming, which immerses us in grainless opacities. This division between man as handler of media and man as consumer of mirages may even mirror the dichotomy between the two most common descriptions of the animal we are: homo faber and homo ludens (24).

In this sense, a mediatic object (like a film) will inevitably be dream incarnate, while a dream-pertaining object will not infrequently rely on phantasmatic mediations forged by the superstructure of consciousness (like memories). In some way, then, the animated cartoon, as a dream that is realized mediatically and a media that aims at the presentization of the virtual, gives rise to a somewhat unprecedented unity between the two faces of human performance. It is simultaneously materiality and facade, labor and otherness, pure device and pure manifestation, machinic synthesis and poetry-vibration.

Having said this, one can finally reopen the range of analysis with a new theoretical toolkit. In the two animated series of the Avatar universe, The Legend of Aang and The Legend of Korra, this relation of univocal centralization between dream and media is supported, on the side of dreams, by a mythological reconfiguration of the phenomenology of elements and, on the side of media, by an installation under certain systems of organization of peoples and territories (historical, political and economic coordinates well located in an internal teleology). The two series are realized, moreover, as a Western praise of an Eastern utopian self-consciousness, that is, they also propose the utopia of a living dream from an orientalist position.

As for the phenomenology of elements developed there, it can very be interesting to consider it in comparison with the phenomenology of elements stricto sensu developed by Gaston Bachelard, for whom it was necessary to dream out of archetypal images and literary frameworks so that these could naturally express the conflagration of psychological tendencies and interests that form them, and that are bound to their parametric webs (25). Bachelard then draws, in a set of books in which he analyzes elemental forces from the standpoint of the free imagination of experience, overflows from these canons and traditions. For example: for him, fire and air are rhythmic, dynamogenic substances, of fast conversion and regeneration, which induce each other reciprocally and only survive in time (26), while water and earth, on the contrary, inscribe themselves in reality as tonified states of matter (27) growing spatially, to swallow and condense. Now, if we compare this perspective with the directorial choices of The Legend of Aang and The Legend of Korra, we will quickly notice that they are close and inter-coherent. The fire benders and the air benders of the Avatar universe “produce” their elements ab nihilo, as if their well-managed hands and a concentrated intention were enough to germinate these flaming or diaphanous bouquets of ephemeral vivacity. Meanwhile, the earth and water benders need the support of a rooted topology, a telluric reservoir from which to extract the raw material to be magicized.

Furthermore, the nomadism of the air benders can be explained by the aerial energy described in the Bachelardian imagination of movement: air monks constantly exercise a “power of becoming” (28) through the inconstant flux of their own bodies, which are implied in each movement and carry themselves with the landscape while bending, rather than contrasting the world to their movements. Opposite to that, the earth, which evokes in Bachelard the reveries of rest (29), is represented in the Avatar world by an inert resistance and passivity to face the sculptoric molding of time, whose force implies an intensity-in-immobility (30) (not infrequently drifting into conservatism and, eventually, cowardice, during the series). Water, which Bachelard interprets, based on the Romantic poetics and primitive cosmogonies, as the substance of dream itself, where an amorphous blackness seems to be ready for an spontaneous fermentation of forms (31), appears in Avatar also in analogy to nocturnal contemplation, meaningful madness, and the mystique of healing. Conversely, the violence and abrasive destruction of fire, its separatory potential (and also its fascinating eroticism) (32), allow for obvious parallels with the ethical position of the Fire Nation in The Legend of Aang, with its invasive-corrosive expansionism of pseudo-colonial overtones.

The flying bison, a classic air monk pet, reaches the Eastern Air Temple in The Legend of Aang (2005-2008).

Also curious, to say the least, is this use of the word “bending” or “folding” to designate the manual control of elements. It is almost as if this sway of natural phenomena and molecular temperaments constituted an origami of natural reality, and such a domination was presented as a “handcraft”, a pedagogical control of inorganic particles. In one of his last books, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, Deleuze argues that matter and soul are homologous precisely because of the morphology of folds: both would present a porous, spongy physiology, forming micro-turbillions and concave intervals vulnerable to the action of soft elastic forces and other variable undulations (33). Deleuze also writes, not without some degree of mania, that the science of the relation between body and world should be based on the mechanism of bounces and flows, whose qualities make them tend and distend, contract and dilate, compress and explode, coagulate and rarefy. In Avatar, the bodies of the benders even seem to be expanded by the elements, which become protheses of their most minor physical inflections. Not to mention that the way bending is represented in the series, how it is formulated in certain attacks and certain defenses during combats, and how it is demanded for social use in the universe of the narratives, also runs into the Bachelardian description of elements: over every discrete elemental exercise there seems to be a wide layering of mythological complexities.

It is interesting to think how, in this sense, the “metal bending” introduced in The Legend of Korra brings along an image of industrial mythopoetics, which Bachelard failed to realize, perhaps because of a certain natural-primitivist righteousness. Metal, as an “element” characteristic of the Industrial Revolution and therefore of the Anthropocene, as a fully artificial substance forged by and for factory work, becomes a general icon of human activity today, an activity which is based on unrestrained technical progress. With this novelty, however, the series also inserts in its universe a dimension of absolute historicity, as if the civilization represented therein had passed through its own modernity, that is, through the discovery of a unique historical time, a march unified as a triumphalist ecumenical breach (34). There is a proper political problem here regarding the temporality of fantasies, which The Legend of Korra seeks to resolve, if not in a damaging way, at least in a rather ambivalent way. We know that there is no objective gradation of development for different societies, and that there should be no single shared destiny for the world’s techno-scientific flourishing (35), but only the infinite multiplication of psycho-geographical placements and their respective (and always diffuse, meso-aleatory) inferences in a common para-linguistic matrix (36). By assuming that a world different from ours achieves the same irruption of historical facticity as our own, Korra also implicitly assumes an anthropologically debatable hierarchy of cultural successions.

There remains, however, a certain (fetishized?) interest in the cultures peripheral to that of the Capital, in The Legend of Korra, and a certain variety of materialities and sociabilities – architectures, fashions, currencies, routines, kinship arrangements, ritualistic practices, etc. – which perhaps makes the series appear as a critical reflection about our current state of axial convergence towards a globalizing liberalism, rather than a masked praise of this futural homogenization. It also – and more relevantly for this text – retains an admiration for the bio- and ethno- diversities of the fabulous, with the emergence of phenomena very alien to science, or at least of phenomena common to science as phenomena alien to it, as miraculous events: carnivorous plants and shifting sands, active volcanoes and infinite swamps, imaginary ecosystems lending to existing ecosystems a decorative tuning, a “roundness” so typical of the dream (37). The characters coexist with these chimerical environments with a special lightness and softness, so as to give their appearance a pleasing surface of internal cohesion. This holds true for both The Legend of Korra and The Legend of Aang as well as for the Studio Ghibli films we referred to earlier. Miyazaki himself recalls in an essay (38) that his films include a worldview full of the splendor of hope, in which the natural is renewed with palpable freshness against every new possible social installation.

For in all these media appearances of the dream, in all these animated fantasies that propose manifestations of an impossibility in being-there, what is recovered is also utopia (i.e., the “non-place”), taking landscapes and figures to their ultimate end through the exaggerating drive of a pre-appearance (39). The animated world is then without causality and without incompleteness, because it is without conditional enchainment: it is plenified. Nevertheless, it does not burst, does not disappear apocalyptically, but achieves certain metastability by a “gradual entelechic modulation” (40), in a fructification that preserves while perfecting, forcing the register (the canvas, the machine, the color itself) to function as a laboratory and a feast of virtual and subnormal effectivations.

It is noteworthy, in Korra, how some episodes will open more honestly to this fructification, to the displacements of the oneiric, instead of dwelling on the realpolitik or ceremonial etiquette of its universe. Good examples are the last chapters of the second season (and in particular chapter 10), when Korra and her cousin Jinora enter the “spirit world”, a realm imbued with a ghostly element that escapes the hitherto known logic of bending. Like the enigmatic reality of Alice in Wonderland (and with such a degree of apparent schizophrenia that it would probably delight and enrage Artaud as much as Alice did [41]), the spiritual world of Avatar seems founded on paradoxes and self-referential senses, which superimpose ambiguous identities on each other – future and past, more and less, active and passive, etc. – in a continuous mystification of empiricism, since our impressions always escape the constructive recognition of the beings that move inside of it (42). Butterflies are made of shining jewels, paths intertwine in a purple maelstrom, trees move like arachnids, recalcitrant paranoias are mobilized to convulse as a giant tapestry. The very creatures and scenes recall those of Lewis Caroll: the tea table, the mathematical chess, the talking reptiles and extinct birds.

A frame from The Legend of Korra’s Season 2, Episode 10 (2013).

However, in Avatar, the images are not fixed on a book page by John Tenniel’s pen, as in the case of Alice, nor are they limited to the reader’s imagination, lacking as it does some good transductive substrates. They last like reality itself, they are “animated” in the original meaning of the word: animus, soul. Unlike painted or described images, animated cartoon images show indestructible bodies (that is, spectral entities, glimpses of the world of immortality [43]) at the disposal of kinesics, of the intermingling of vectorial charges and cogrediences (couplings of time and space [44]) in a way so common to reality that they seem to be under the yoke of the same temporality, under the same regimen of periodic persistence as reality. This is why animations falsify the magical with such skill, why they anthropomorphize the cosmos and cosmify man (45), why they allow for the upheaval of the panpsychic and the theandric. They are simultaneously associated with an absolutely real cadence and an absolutely unreal display. And so the four primordial elements of Avatar are humanized with ease, and “bend” – they find in the bender their tropisms.

Above all, however, Avatar seems to pay a compliment not to utopia in general, but to a form of Eastern utopia, as we were saying. It is a love letter written by a West that currently only cultivates gloomy futures, spat out by a dark logos – the most diverse ends of the world or other dystopian singularities (46) – to an East that has apparently already fallen apart, but which remains in nostalgia and alienation as a symbol of solemn pacification and cooperative extinction of egoic intuits. After all, if in Eastern philosophy reality itself is already a dream (47), an illusory veil and a reification of absolute nothingness (48), we could oppose the Eastern utopian dream to the Western one as Bloch did, by analogy with dreams of day and dreams of night, respectively. For Bloch, while the compositions of the dreams of night (or the Western utopia) recombine in the details of an inexplicable and voracious desire, in a will of infinite hunger, the compositions of the dreams of day (or the Eastern utopia) open windows to an otherness of the here-and-now, and come from the expansion of the world downward, not forward. It is a matter of a “wanting-to-live-better”, a “wanting-to-know-better” (49), which, contrary to vulgar ambition, does not rest on a productivist, quantitative amplification by piling of data, but on the expansion of the interiority of consciousness itself, which takes possession of blindness (50) in order to illuminate its paths with it, which integrates itself with negation in order to find genuine attention inside of it.

The acceptance of the primordial unity of spontaneity, so promoted by Kumaraja, Longchenpa, and other sages of Tibetan Buddhism, and which Avatar brings up almost at every moment as its underlying ideology (and even, occasionally, as an explicit proselytism), implies an encounter with utopia in the completeness of one’s own experience, in the unelaborated datum of present existence. But, more than that, the predicates of the animated fantasy cartoon as a genre – and this is very clear both in the series of the Avatar universe and in Studio Ghibli’s films – realize the purified inner experience by manifesting the unattainable, propitiating the self-emergence of the utopian state in the guise of making us perceive the world itself as a resistant dream that germinates from the universal background of encounters.

___

References

1. Flusser, Vilém. Língua e realidade. São Paulo: Annablume, 2007.

2. Langer, Susanne K. Feeling and Form. London: Macmillan Publishers, 1953.

3. Flusser, Vilém. Natural:mente – Vários acessos ao significado de Natureza. São Paulo: Annablume, 2011.

4. Bloch, Ernst. O Princípio Esperança. Vols. 1-3. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2005.

5. Flusser, Vilém. Natural:mente – Vários acessos ao significado de Natureza. São Paulo: Annablume, 2011.

6. Cf. some aesthetic phenomenologies of music, such as the works of Gabriel Marcel, Romand Ingarden, Mikel Dufrenne, Vladimir Jankélévitch or Giovanni Piana.

7. Famously, Proust writes his magnum opus In Search of Lost Time from the reminiscence of a single scent from his childhood. A good analysis of this relation between affective memory and its differential melting in echolalia based on the proustian literary body can be found in some of Deleuze’s books dealing with the question of duration, such as Difference and Repetition, Bergsonism, and, obviously, Proust and Signs.

8. Cf. the wonderful interpretation of Sappho made by Anne Carson in Eros, the Bittersweet.

9. Bachelard, Gaston. Estudos. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2008.

10. Borges, Jorge Luís. “La Luna”. In: Poesía completa. Madrid: Debolsillo. 2011.

11. Langer, Susanne K. Feeling and Form. London: Macmillan Publishers, 1953.

12. Bloch, Ernst. O Princípio Esperança. Vols. 1-3. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2005.

13. Ibid.

14. Sakai, Naoki. Translation and Subjectivity: On Japan and Cultural Nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

15. Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. “Martin Heidegger e seu interlocutor japonês: A respeito de um limite da metafísica ocidental”. In: Serenidade, presença e poesia. Belo Horizonte: Relicário Edições, 2016.

16. Heidegger, Martin. Ser e tempo. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014.

17. Ibid.

18. Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

19. Morin, Edgar. O cinema ou o homem imaginário. São Paulo: É Realizações, 2014.

20. Bachelard, Gaston. A poética do devaneio. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2018.

21. Ibid.

22. Cf. the works of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht about the “production of presence”, as well as the history of visuality proposed by Friedrich Kittler in Optical Media.

23. Bolter, Jay David & Grusin, Richard. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

24. Flusser, Vilém. O universo das imagens técnicas: Elogio da superficialidade. São Paulo: Annablume, 2008.

25. Bachelard, Gaston. A poética do devaneio. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2018.

26. Id. Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement. Dallas: Dallas Institute Publications, 2011.

27. Id. A terra e os devaneios do repouso. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2019.

28. Id. Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement. Dallas: Dallas Institute Publications, 2011.

29. Id. A terra e os devaneios do repouso. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2019.

30. Ibid.

31. Id. A água e os sonhos. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2017.

32. Id. A psicanálise do fogo. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2008.

33. Deleuze, Gilles. A dobra: Leibniz e o barroco. Campinas: Papirus, 2007.

34. Koselleck, Reinhart. Crítica e crise. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 1999.

35. Cf. the recent works by Yuk Hui about the question of cosmotechnics and technodiversity via the specific case of China.

36. A (probably caricatural) reduction of one of Lévi-Strauss’ arguments in The Elementary Structures of Kinship.

37. Bloch, Ernst. O Princípio Esperança. Vols. 1-3. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2005.

38. Miyazaki, Hayao. “On the Banks of the Sea of Decay”. In: Turning Point: 1997-2008. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2014.

39. Bloch, Ernst. O Princípio Esperança. Vols. 1-3. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2005.

40. Ibid.

41. At a certain point in his life, Artaud accused Lewis Caroll of having travelled in time to steal his ideas for the writing of Alice in Wonderland.

42. Deleuze, Gilles. A lógica do sentido. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2009.

43. Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

44. Cf. the explication of Alfred North Whitehead about his concept of “cogredience” in The Concept of Nature.

45. Morin, Edgar. O cinema ou o homem imaginário. São Paulo: É Realizações, 2014.

46. Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo & Danowski, Débora. Há mundo por vir?: Ensaio sobre os medos e os fins. São Paulo: ISA, 2017.

47. Longchenpa. Finding Rest in Illusion: The Trilogy of Rest, Vol. 3. Boulder: Shambhala Publications, 2018.

48. Cf. the philosophies of the so-called Kyoto School (with special attention to Nishida and Nishitani), which sought to mix the ontological-existential analytics of Heidegger with ancient Eastern philosophies, finding, in this trajectory, a fertile notion of “absolute nothingness”, or non-Being, in opposition to the Heideggerean (and Western) notions of Being and nothingness alike.

49. Bloch, Ernst. O Princípio Esperança. Vols. 1-3. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 2005.

50. Cixous, Hélène. The Hélène Cixous Reader. New York: Routledge, 1994.