It is typical for any modern ideology to turn to scientific discourse as a way to self-naturalize. The science writers, the least conscious abusers of science, typically try to connect it to ‘common sense’ in the most exegetical, uncritical manner; science in their works never acts, and is instead quoted. In doing so they, however, make visible the power of scientific discourse itself, as only in this type of discourse – and never in the consciously ideological writings nor in the science papers themselves – we can hear science speaking, that it says this and that. Science is thus constructed as a subject, and this allows for a new space of critique – not the critique of the relation of its utterances to the truth, but rather the critique of its subjective structure, and most importantly of the narcissistic image that this science-subject has of itself. As is the deal with such images, what science communication can thus reveal is that science is actually much more complex, interesting, ambiguous and free than the way it sees itself, at the painful cost of losing the faux-stoical image to which it holds on fearfully as its only claim to truth.

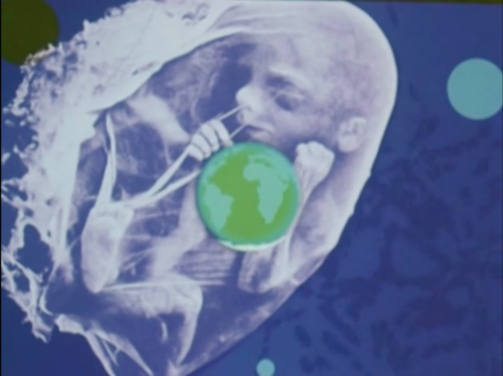

The educational videos, made specifically for vocational training, are an especially interesting example of the formation of science as a subject, as their purpose is neither to advertise science to the general public nor to make an ideological statement backed by ‘scientific facts’, but to educate the future scientists and technologists. However, it’s not just knowledge that is transferred in such videos, as the medium doesn’t really help conveying complexly structured information in an unambiguous way. The goal of an educational video is to provide a dimension of fantasy to what in a textbook can only and necessarily be dry symbolic speech – to help the students to participate in the science-subject.

Vladimir Kobrin, (1942–1999) was an avant-garde Soviet movie director, who from the very beginning of his career was forced to shoot educational videos. He used this limitation to produce incredible, and aesthetically and technically brilliant films on topics such as chemical transport through cell membrane. The resulting movies are first and foremost seen as a testament to his talent and fantasy, and praised for the vague, romantic, and profound worlds they persistently impose on viewers and on science. Indeed, the legible philosophical content that he masterfully inserts in scientific videos is very appealing as a romantic meditation, but this is hardly his most important achievement. What I think is much more interesting in his videos is how he confronts scientific discourse. Rather than just quoting the theories, he tries to force science itself to speak through the language of cinema.

Three periods of these attempts can be distinguished in Kobrin’s works. The first period, mostly concerned with physics, is structured as a typical of scientific videos – at first, the image obediently follows the voiceover, providing an assortment of visuals as the backdrop to whatever the lecturer is saying in given moment. This might be seen as a lucid dream of science; Kobrin looks for ways to produce the authentic account of how the science’s imagination can be presented. However, the video-sequence is but a follower of speech here and thus always a step away from the science-subject.

In the second period, mostly concerned with biology, Kobrin starts to do away with the sensible speech by replacing it with the recordings of monologues of by schizophrenics. The movies remain educational nonetheless, but as the speech breaks down, the subject-forming role is by necessity fully assumed by video-sequence. Video doesn’t allow the same restrictions on its content as science-subject imagines itself to follow in speech, and Kobrin himself is far from trying to fake these restrictions. He uses the strategies he developed in the preceding period to provide video-sequences that would be ascribed to the science-subject but not informed by scientific discourse. The transition might be informed by the fact that, while physics stems from the assumption of the mathematicity of the world, biology (of that and the preceding time) is rather based on its teleology, thus much more susceptible to the less abstract language of cinema.

The third period, following the fall of the Soviet Union, marks the moment when Kobrin is finally allowed to speak for himself and not from the science-subject position. While his movies of this period remain beautiful, well-made and attentive to the world, the newly available romanticism seem to reduce their subversive quality. They provide, however, an interesting contrast to the preceding period, demonstrating quite clearly that the Kobrin-subject differs from the science-subject and that the latter provides the works with the eerie internal consistency unavailable to the movies made later by Kobrin freed from Soviet limitations.

One of the most important strategies used by Kobrin to make science speak is his use of similarities he finds between the video and his subject. This is done both implicitly and explicitly, as in The physical foundations of the quantum theory, where he explains how the discreteness of the quantum world is mirrored by the discreteness of the videotape. In other, subtler cases he can, for example, illustrate some specific quality of an object – say, its variability – by holding the object still but performing various video effects over it. This makes visible the objectivation, the work of the object-creation by science-subject, which of course is itself formed in the process of the camera becoming science.

He looks for and uses many types of similarities between video-art and science, including those that are inaccessible to speech. An interesting example of this strategy is his use of specific objects. One of the most often encountered images in Kobrin’s works is a key. The key moves around, looks for something, is copied and photographed, and even sometimes actually unlocks the locks. While this might seem like a pop-science cliché, the key that actually makes it into Kobrin’s works is a very specific key. It’s a specific character of the story he tells in his very first movie – the story of Becquerel stumbling upon the radioactivity.

That’s how the story of Becquerel is usually written down: trying to see if uranium crystals would emit rays after exposure to sunlight, he’d place ‘coins and other thin, metallic objects’ between the crystals and the photographic plates. However, should we look for the photographs he made in an attempt to supplement our reading, instead of coins we rather find pictures of Maltese cross. This makes immediate sense: the silhouette of the cross is a much more obvious photographic evidence, as its shape is more specific; it’s a better image for us – but by the same token, it should actually had been a better image for Becquerel himself, as it was exactly the photographic evidence that he looked for. The change of medium forces thus a minutiae but pleasant revelation, bringing us closer to the actual process.

Kobrin, however, uses neither images – he uses the actual key, the third ‘thin, metallic object’ of the Becquerel’s ad hoc exhibition. It can serve as an additional level of critique. The coin is the best material for scientific writing as it is abstract in every way – not only in its form, but it is also as money, it is seemingly abstracted from its history and its role as a specific object, as it has changed too many hands to be a particular coin. We see that the coin helps to promote a very specific image of what science is, or rather, of what science can dispense of: the particularity and aesthetics of the objects. However when the cross is chosen for the photograph, it is chosen for the additional meanings – after all, the image now is of a glowing, black cross. By returning the object into the science, photography adds a level of mysticism which negates the whole project: the cross now is an aesthetic exaggeration, not a revelation of the objective facts regarding the scientific project. Kobrin does away with the mysticism by showing us the key. The technical reason to use the key (e.g., its asymmetric shape which makes it better suited for the animation) supplements the ideological component of the coin and the cross, both of them questionable images in the Soviet Union.

The particularity of the choice of objects makes no sense on the abstract level yet it is of utmost importance on the perceptual level which is at the same time a necessary and yet disavowed part of the process. Amusingly it is indeed considered a mystery by the historians of science, why did Becquerel develop those photographs (he himself thought he didn’t expose the crystals to the sun long enough and thus wasn’t supposed to expect to see anything on the pictures). It is hard, however, to imagine this being a mystery if the aesthetic part of the scientific process was not disavowed.

Kobrin is a representative of the late twentieth century, full of hope and naïvete, when combining science and art constantly received superficial support. In the eyes of the pop-scientists, science has a self-image as a source objective, cold and rational discourse, opposed to art which supposedly abandons its relationship to the truth by ignoring the values of science. Thus the attempts to combine these two are doomed to fail if only because of how important each of their negations of the other one is for their respective identities. Kobrin’s work “hystericizes” science through art, exposing the attempt by both science and art to preserve their identities as narcissism. He embraces both categories, making them regress to the raw sensual mess in which we can divine their mythic unity.