The global political crises of the last decade have renewed a call for the consideration of decolonial strategies as an effective response. As peripheral the place and voice of art in these debates might seem, from the time of the Paris Communes to the present, art has been corresponding to revolutionary and transformational developments around the world. Thus it is no surprise that the question of decoloniality is now taken up by art and artists as the theme and the anthem. In the smaller world of art and culture, which inevitably follows the larger social world, decoloniality and colonialism have been picked up as both new frames of reference and lenses for reformulating issues and problems, as well as ways to restructure relations of production (to use Marxist terminology), in the world of art itself.

Decoloniality in arts is both a way of seeing, a descriptive technology, and a way of doing, a prescriptive one. This is why an examination of the roots of this concept is necessary, if decoloniality as a “praxical” solution (a word I use to describe a thing which is both ideal and pragmatic, theoretical and practical) is to be embraced. Here you will find an indexical genealogy for the terms associated with these trends, linking them to previous theoretical paradigms as well as to a sharp criticism of such overlapping concepts.

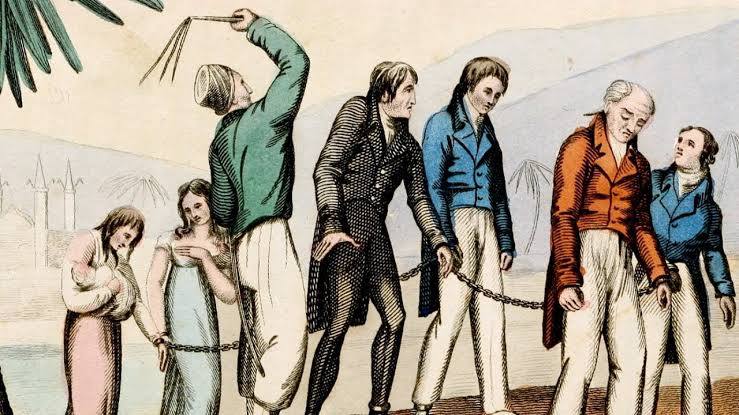

Anticoloniality, an ideological and political position, whose adopters seek to destroy aspects of the colonial framework that are embedded into a form of global politics and dynamic of behaviour that reinforces patterns of colonial domination, whether aware of it or not. Among anticolonialists are people who rise against any type of imperialist repression, be it material or not, including, in this case, intellectuals and revolutionaries of a diverse range of countries and beliefs, like Mohammad Hatta (1902-1980), Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), Thomas Sankara (1949-1987), Marcus Garvey (1887-1940), and Abdias Nascimento (1914-2011).

Anticoloniality began by fighting the systems or policies of larger and more industrially and economically advanced nations with unjustified authority over people or territories other than their own. However, in terms of an alternative, it often birthed new sovereign nations in place of the colonial political and economic infrastructure. Most anticolonial movements began to be heard and effectivized only after the emergence of finance capitalism – always a global force, as is imperialism, which has been defined as the evolutionary offspring of colonialism – a new paradigm that already was the death knell of the 19th century European idea of sovereign nation states.

Offering sovereignty to new people was not unlike selling an outdated European technology to those who could possibly need a better system for the incoming era of global finance capitalism, in which nation states were acquiring a contrast decreasing of their actual sovereignty compared to large states with stable and dominant currencies (like the UK). Often conflating their struggle with anti-imperialism or at least posing like it, anticolonialism had to base its legitimacy and demands for power on the authenticity of a nation, its history and culture, rather than on a universal struggle by localities against economic and military superpowers (like the USA) or allied groups of nations (like NATO), that on which true anti-imperialism bases itself. Whether in India, Algeria, or Indonesia, these struggles not only were led by those who had studied in the oppressors’ university, but were unable to offer political legitimacy based on cultural identity. It is easy to see why, within a generation or two of the leaders, these movements were mostly defeated. How could this be avoided when the leaders of the initial anti-colonial resistance movements studied an outdated mode of governmentality in European universities or institutions created by Europeans and supplied with knowledge stemming from an old European perspective?

Postmodernity, an umbrella-term referring to a series of trends in the fields of philosophy and art in the second half of the 20th century that produced conceptual breaks in relation to modern/modernist grand narratives and supposed “dogmas” as well as to the value-systems derived from the European Enlightenment, including but not limited to: reason, morals, beauty, truth, identity, hierarchy, reality, nature, language, progress and knowledge. It is represented by many different schools of thought and theoretical approaches, such as deconstructionism, post-structuralism, neo-marxism or post-critique, and is articulated by thinkers such as Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), Jean-François Lyotard (1924-1998), Fredric Jameson (b. 1934), Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995), and Michel Foucault (1926-1984), most of them French, since the movement started to become really influential after the French protests of May 1968 and was built upon French philosophers of the so-called continental tradition.

As a school of thought that inverted the German Nazi philosopher Martin Heidegger’s essentializing concept of “Being” and fortified that inversion’s application to the rapidly cybernetified western societies, postmodernism proposes a negation of systemic thinking and analytical approach to complexity. Some scholars argue that postmodernism would be impossible without the contribution of anticolonial thinkers and scholars working in western universities.

Accordingly, it was the interaction between non-Western intellectuals and their western counterparts in academia that helped to provide an inside view of the western empire as corrupt and outdated. Postmodernism was the basis upon which later iterations of anti-modern and anti-western attitudes (particularly via feminism, black studies and queer theory) took root. Opposing all forms of central power and planification rendered postmodernism’s critique of modernity attractive for the incoming neoliberal order. The cultural managers of said order adopted it as a way to reform the humanities, arts and social sciences, purging them from any content that could uphold the ideals of the European Enlightenment and modernity as its guiding path. These days, postmodern generalized claims like “knowledge is power” or “things only exist in discursive forms” have become a barrier to the production of knowledge which actually contradicts these claims.

By denouncing all of the west’s legacies, postmodernism has both blocked the way out of the western world for its own emancipation as much as it has given license, to anyone who can claim to stand outside of the dominant groups in the west, to demand that unverifiable personal experience is taken as pure knowledge in a frenzied and fetishized version of epistemological diversity. Meanwhile, by intellectually justifying and facilitating the transfer of production of goods to the non-western labour markets and helping to save western capitalists’ money, the postmodern ideology is giving false strength to the very societies that are being double exploited by the west. A sense of false moral and ideological superiority prevents these places from trying to find a better solution for their burning, very concrete and very real, economic and political problems.

Postcoloniality, an adjective referring to the set of studies that try to analyze the social, psychological, philosophical and artistic effects of colonialism in marginalized countries, paying special attention to the symptoms of it that appear in literary works from countries colonized by European powers during the time of their domination itself. This movement started in the 1950s with thinkers like Aimé Césaire (1913-2008) and Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), who were from colonized countries but studied theory in European institutes, and it was first systematized in the 1970s by Edward Said (1935-2003), who in his book Orientalism, criticized the western view of Asian and Middle Eastern cultures as a fetishized hermeneutic based on colonial frameworks of thought. Since then, postcoloniality has become a wide term referring to new cultural conditions for thinking that accounts for the differences imposed by the history of colonial subjugation.

Postcoloniality is one of the most successful offspring of postmodernism. There isn’t a field of study in the humanities or social theory – anthropology, history, cultural theory, art theory, ethnic studies, to name a few – that has not been impacted by the main tenets of postcolonialism. By placing colonialism at the center of modern era’s history, it supposes that knowledge and culture in the west were mainly produced to uphold the colonial infrastructures of power. And since the theory depends on the postmodern notion of discourse, the proof of this culpability must be found in texts that can answer an oppressed society’s real historical and social issues. Postcolonial theory assumes that the operating logic of imperialism, as a 20th century paradigm, more or less follows that of colonialism, with differences only in degrees and not in quality.

Postcolonialism supposes that the misconception of the Other is at the root of the inequality between these territories. In other words, for most forms of postcolonialism, it is racism that causes colonial domination and not the other way around. It is not as if a power system produced a superior ideology to cover up its dominating operation but it is a lack of proper understanding of the Other and an inflated sense of self-worth in Europeans that causes them to be racist. Without discounting the complex relationship between these two phenomena, one cannot deny that racism’s institutionalization, both locally and globally, had more to do with the need for economic exploitation, instead of the opposite.

It is easy to reverse the order of this relationship in an idealist manner, if theorists cherry pick their evidence for the roots of colonialism from literary novels and other forms of artistic text rather than historical evidence or contemporary forms of social reality. This kind of culturalism is empowering when it enables us to claim that western culture tends to have a dominating attitude towards the world and assumes the Other to be inferior, but the other side of it is a kind of naive naturalism that also translates into attributing victimhood and a lower moral status to non-western societies that have been subjected to the power of the west.

Subalternity, a concept developed by Indian scholars Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (b. 1942) and Dipesh Chakrabarty (b. 1948) which gained traction in the 1990s. Subalternity is very much informed by the Indian experiences of resistance against British imperialism and the struggle for independence. the concept refers to a kind of second-class citizen that appears in the context of a colonialist domination. In this sense, subaltern is anyone who is alienated from the main space of cultural reification and hegemonic discourse – the subaltern is more than merely “oppressed”, since it is also denied access to the means for its own liberation, to its own voice.

Much like other concepts spurging from postmodernism, the notion of the subaltern is useful to a certain extent, but does not solve the problems it sets out to address, mainly reversing cultural and political injustices exercised by the global south by the global north. Rather, it starts from the desired results and leans in the framework of Marxist class struggle to unfold into a new and ideal strata. Letting the subaltern speak is only effective while it’s performatively speaking. Thus, by eliminating the liminal layer of subalternity, which, according to the theory, sits at an advantageous position between the oppressor and the oppressed, the gap between the two grows without the subalternity being able to interface the two. There’s no advantage in ridding an oppressed class of its subalternity if it isn’t also ridden of the underlying oppression itself.

It’s important to remember the extent in which the subaltern scholars work within the US-American academic discourse, and how much their labour is a tentative expression of the struggles of the middle and upper middle class people of colour in the academic world. It seems as if they were relating their unfair professional lives to young, international, and mostly white and European spoiled students. In this respect, subalternity reflects trends in how systemic discrimination in these fields could be circumvented using logic and reason, and more importantly, language itself, through opposition.

Decoloniality, the term for a school of thought majorly linked to Latin American thinkers who intended to liberate philosophy from what they saw as a Eurocentric episteme. It heavily criticizes the supposed universality of western knowledge and values and their predominance in the discourses of colonized countries. It was developed in the beginning of the 21st century by scholars such as Aníbal Quijano (1928-2018) and Walter Mignolo (b. 1941), who argued for a new type of underlying logic and semiotics of thought production that completely disregarded the European matrix of meanings and speculative boundaries, as well as traditional European institutions such as the university and the museum. They argued specially for the reversal of postcolonialism itself (which for them was still based on a European framework of thought, despite being in opposition to it) and for the recovery of indigenous cosmologies and practices. The reason for this complete disbanding of European philosophy is that for them all of these concepts serve to perpetuate inequalities and discriminations, which are codified into the functioning structure of colonized countries. In this sense, decoloniality is a “mode of thinking and acting” that ignores the conventional pillars of western civilization in favour of an “epistemic disobedience” that reconstruct the whole of society from another standpoint, supposedly purified of colonial traces.

It is not difficult to see how reactionary this position can become if you take it to its logical conclusion. A case in point was the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which caught the attention of anticolonial, postmodern and postcolonial thinkers around the world, a revolution that seemed to walk in the path of anti-western and anti-modern decoloniality. Within less than a decade, Ayatollah Khomeini’s utopian dream of complete sovereignty and secession from western powers transformed the country into an ethnofascist nightmare. Tens of thousands of leftists and seculars were executed with at least another hundred thousand in prison, all under the accusation of being western minded or direct spies of the west. In the last 40 years, the Iranian society has slowly moved towards an institutional form of religious ethnofascism, a poisonous blend of the old Iranian nationalism as its content repackaged with a Shia Islamic identity as its form.

Isn’t this disregard for modern and western value-systems and the return to an immemorial folklore, apparent in the official culture of places like Iran, precisely the demand of fascist esoteric writers such as Julius Evola or René Guenon? This is why decoloniality cannot be purely considered as a progressive and left-wing movement, since at least large parts of it clearly belong to the fascist lineage of radical conservatism with prehistoric roots in the west. Totalized conceptions of decoloniality which ignore its dark side and concentrate solely on its progressive potentials lack coherence. It reads as an immature eagerness for blind revenge that cynically entails the destruction of what we have collectively built so far – just like the fascists, in the Filippo Tommaso Marinetti version of Futurism.

Colonialism has already happened and has already been condemned by the collective intelligence itself in an initial attempt of self-regulation. The accusation stands, revealing itself before the eyes of its witnesses. Why, then, would we even pretend to purify colonized societies of their traces of colonization, if such accusations can never be cleared, if they can never be forgotten? This is why we can comfirtably claim that there has never been a Peru, a Bolivia, or a Brazil outside of the boundaries of the constituted colonization and the struggle against it. The historical debt seems unpayable already. More than that: there’s no pure “un-colonized” society to which we could return or even arrive, since the image those colonized societies make of themselves is also obscured by the deep effects of colonization.

* * *

It is impossible to define which movement of history is a result of colonial dynamics and which one isn’t. Since they are all confounded to this very core, throwing away every single dimension of colonialism would mean throwing away these advancements with them.

Instead of fermenting an epistemological setback based on a precritical embracement of decoloniality, we could simply advance with those practices comparatively, proposing creative ways of articulation between diverse cosmotechnics in and out of a western frame. If there are really such epistemological differences and if there really are novelties to be rediscovered in these originary cosmologies, they must all be set free to face each other in the game of rational, or philosophically substantial thought, without guilt or morality. The glorification of postcolonial and decolonial theories could even be considered offensive as much as one of the tenets of human dignity is the capacity to be wrong, to be judged fully and sincerely. What decolonial thinkers seem to have towards indigenous communities’ intellectual production is condescendence.

Is there anything more western than the capacity to judge your own civilization as the Other, to see it as evil and peripheral in the ecosystem of cultures? Claude Levi-Strauss once wrote that every society, indigenous or not, in America, Africa and Oceania, believes it is in the center of the universe – every society is founded exactly by awarding magical properties to an object or place (such as a mountain or a river) which must correlate to the axis of the galaxy, the phatic spine on which the gods must have climbed in the dawn of days.

Those who stand against the forces of western enlightenment and modernity are ultimately doing so within the ranks of the western world, be it in academia, arts, or the media. These efforts, while challenging the existing systems, are essentially their reformation, and, if succeeding, they would improve the existing system of western, modern society. These efforts are part and parcel of an evolving system. This is perhaps why, upon a deeper inspection, we can verify that anticolonial, postmodern, postcolonial, subaltern and decolonial theorists and defenders are quintessentially western in either form, or content, maybe even both, and their seemingly oppositional journey in politics or philosophy is, in fact, nothing but the continuation of modernity. It is maybe (how surprising) only through the passage of time or by a look into the rearview mirror of history can we assess how much of these efforts actually will decrease or diminish western supremacy and colonialism.

The larger project of modernization, which includes its critique, is like a shadow cast by utopian desires of the people around the world over the institutions of power. They follow these aspirations and dreams, and their intensity corresponds to the light and heat emanating from them.

—

This text was first published in a printed edition of Arts of the Working Class. Special thanks to Romulo Moraes for his help with the research and writing of this text.