Synopsis

Reza Negarestani’s “Intelligence and Spirit”1 stands as an intersectional exploration of philosophy, mathematics, logic, and computer science. The work is an intricate tapestry weaving together threads from various disciplines in order to present a comprehensive understanding of intelligence, in both its human and artificial manifestations.

Negarestani draws from category theory—a branch of mathematics that delves into abstract structures and relationships. He employs this to frame the book’s philosophical arguments, particularly when discussing the structure and function of intelligence. In this fashion, the concept of Chu spaces is used to express Kant’s picture of the mind, allowing for a nuanced interaction between sensing and thinking, empirical computation, and logical computation.

Diving deeper, the book’s exploration of type theory goes beyond academic exegesis. It serves as its foundational pillar, emphasizing the constructivist nature of knowledge and suggesting that intelligence is inherently about constructing knowledge. This ties seamlessly with proof theory and the Curry-Howard correspondence, further blurring the lines between computation and philosophy. Negarestani posits that programming, in essence, is a philosophical endeavor.

One of the standout features of the book is how Negarestani incorporates the cobordism of René Thom. Cobordism, an equivalence relation between manifolds, is used to illustrate the interconnectedness of ideas and the continuous transformation of knowledge structures. This mathematical concept serves as a metaphor for the fluidity and transformation inherent in the process of thought.

Furthermore, the book hints at the use of functors, drawing inspiration from William Lawvere’s interpretation of Hegel. This offers a dynamic and fluid understanding of identity and consciousness, suggesting that the self can be viewed as a mathematical structure that evolves in relation to other structures.

Linear logic and ludics are also explored, emphasizing the non-static nature of reasoning and the playful (ludic) nature of thought processes. Negarestani introduces Jean-Yves Girard’s ludics as a paradigm that reflects the logic of dialogue, bridging syntax with semantics.

The concept of learning machines is reached into on the computational front, through critical examination of the idea of a universal learning machine and its implications for artificial general intelligence.

The philosophical underpinnings of the book are further elaborated by Hegel’s characterization of Geist or Spirit. Hegel’s conception of the community of rational agents as a social model of mind is central to Negarestani’s thesis. This “intertwining of semantic structure and deprivatized sociality enables the mind to posit itself as an irreducible ‘unifying point or configuring factor.’”2

At its core, “Intelligence and Spirit” is not only a technical book, but also a detailed exploration of the nature of intelligence. It testifies to the deep connections between computationalism and transcendentalism, offering ground-breaking and thought-provoking insights. In doing so, it challenges traditional notions and pushes the boundaries of interdisciplinary research.

Frameworks for Intelligence

Among the various philosophical and theoretical frameworks in which the book delves, certain of them deserve special attention. Type theory and ludics are among these. Below, we present a paraphrasing of Negarestani’s use of such concepts.

Type Theory

1. Context of Mathematical Structures: Negarestani touches upon the generality of category theory and its suitability for studying mathematical structures. He emphasizes the importance of context in appraising and applying mathematical models, suggesting that without proper context, the application of a model can be arbitrary and distortive.3

2. Types and Functions: Types are discussed in a mathematical context, suggesting that these can be understood as functions that compute specific terms. Negarestani introduces concepts like type constructors, term or object constructors, and type destructors, which are essential for understanding the introduction and elimination of types.4

3. Universe Types: Negarestani explores the concept of universe types, suggesting that these help differentiate the data under consideration. He aligns this with Plato’s thesis that thinking determines differences, and emphasizes the importance of carving at the joints of things.5

4. Philosophical Discourse: He touches upon the operators of philosophical discourse as encompassing types of modes of cognition. They are approximated to universe types and the investigation of thought is considered as the type of types (Type0).6

Ludics

Negarestani introduces ludics as a pre- or proto-logical framework for analyzing logical and computational phenomena at an elementary level. He emphasizes the continuity between syntax and semantics achieved through an interactive stance toward syntax.7

1. Interactive Logic: Ludics are presented as the logic of dialogue, through emphasis in its interactive nature. In ludics, speech acts naturally evolve through interaction, with semantics unfolding through the dynamic impact of syntax.8

2. Speech Acts in Ludics: Referencing Samuel Tronçon and Marie-Renée Fleury, Negarestani defines speech in ludics in terms of three elements: the speech acting competence, the test (an interactive situation), and the impact (the effect of the interaction). He suggests that speech acts in ludics are essentially the normal form resulting from the normalization of two interacting designs9.

3. Pragmatic Dimension of Language: Highlighting that ludics brings to the foreground the logico-computational phenomena implicit in the pragmatic dimension of language, Negarestani contrasts this with other theories. It is suggested that for ludics, the generation of rules and the capacity to reason are inconceivable without interaction.10

In essence, Negarestani’s exploration of type theory and ludics offers a deep dive into the intricate relationship between syntax, semantics, and interaction, in the context of intelligence and spirit.

Carnap, Sellars and Brandom

Here is a summarised map of the connections between the three thinkers as established within the book.

Carnap’s Vision of Language: Rudolf Carnap’s perspective on language is presented as a logical-syntactic view, which is not anti-semantic but rather sees syntax as “semantic in disguise.”11 It emphasizes the importance of “disenthralling language from established semantic rules or representational concerns.”12 This approach is not about “forgetting”13 semantics but adopting an “unprejudiced”14 way of understanding it.

Carnap and Induction: Carnap’s thesis on the possibility of constructing an inductive learning machine is highlighted. Such thesis explores the idea of induction as the degree of confirmation. While Carnap defends the inductivist perspective, Negarestani suggests that this approach faces challenges, especially when considering predictive induction. However, Carnap’s sophisticated and nuanced stance on this issue is recognized and defended against criticisms from philosophers like Hilary Putnam.15

Carnap’s Conceptual Engineering: In Carnap’s view, as elaborated by André W. Carus, “the ascent from ordinary language to an engineered one does not suggest the replacement of the former by the latter.”16 Instead, it emphasizes the evolution of language and the importance of rational scientific Enlightenment.

Sellars, Carnap, and the Logical Space of Reasons: Carus discusses the connection between Wilfrid Sellars and Carnap, particularly in the context of the logical space of reasons. This suggests a shared philosophical space where both philosophers’ ideas intersect.17

Brandom’s Engagement with Carnap: Robert Brandom’s approach to language and semantics is contrasted with Carnap’s logical-syntactic view. While Carnap focuses on the structural aspects of language, Brandom emphasizes the rule-governed framework and the interaction of its users. Negarestani suggests a continuity between the two philosophers’ perspectives, with Brandom building upon and extending some of Carnap’s ideas.18

Sellars and Cosmopolitics: Sellars, following Plato, introduces the idea of cosmopolitics or cosmological politics. This “new paradigm for the politics of the Left”19 emphasizes not just intersubjectivity but also “a renewed link between the subject and an impersonal objective reality.”20

Sellars and the Craft of Philosophical Living: Here, it is worth quoting Negarestani at length: “In his engagement with Plato, Sellars, identifies action-principles and practices of craft as belonging to phusis (nature and objective ends), in contrast to nomos (law and convention or social norm […]). In Plato’s account of craftsmanship, purposive actions are neither conventional”21 nor purely based on rational norms, but are influenced by both.

Brandom’s Inferentialist Pragmatism: Brandom’s approach to language involves considering it not merely as a symbolic medium—like we mentioned above, language is seen as a rule-governed framework, intertwined with the interaction of its users. This interaction integrates all necessary capacities of agents. Brandom’s pragmatism can begin with a minimal set of rules, and more rules can be established as interlocutors interact.22

Brandom and Expressive Rationalism: Brandom emphasizes the importance of “understanding how we can adequately describe and explain ourselves and the world.”23 This can lead to consequential changes in the world, “blur[ring] the boundaries between cognitive engineering of autonomous agents and the construction of advanced sociotechnical systems.”24

Brandom on Sapience and Sentience: Brandom introduces the duality of sapience (wisdom or intelligence) and sentience (the capacity to feel or perceive). This distinction is crucial for understanding the nature of intelligence and its realization.25

Dependent Type Theory

By the end of “Intelligence and Spirit,” dependent type theory is situated in the context of understanding the expressivity and structure of types, particularly in relation to cognition and the nature of intelligence. The following is a distillation of how dependent type theory is presented in the book.

Dependent Types and Expressivity: Dependent types are introduced as “crucial for increasing the expressivity of types.”26 A dependent type is described as a function of elements of some other type. For instance, the dependent type D(y), representing the days of the year, is a function of the element y of the type Y of years. This is because not all years have the same number of days. “In other words, D is a type in the context Y or, alternatively, for each y in Y there is a type D(y).”27 Negarestani provides us with a further example: the “dependent type P: Practice -> Type, which is the property of practical claims. P(c) can be seen as the proof or program that claim c has property P, and not some other property.”28

2. Universes and Types of Types: The concept of universe types or the hierarchy of types of types (e.g., Type0: Type1,Type1: Type2) is introduced. These are types whose terms or objects are types. Universes are generally introduced to avoid paradoxes, such as Russell’s paradox. The hierarchy of types of types can be relaxed so that judgments and constructions can be parameterized over all universes rather than specific universe levels.29

3. Relation to Homotopy Type Theory: The parameterization over universes or levels of types of types, especially in the context of homotopy type theory, is referred to as universe polymorphism. “A universe is polymorphic when a proof, definition, etc., is universally quantified over one or many universes. […] this universal quantification creates a type ambiguity, [which] should also permit […] explicit quantification over specific levels or universes” when required.30

4. Types as Forms of Judgement: Types are understood as forms of judgment or Kantian categories. In this framework, a proposition A is a problem whose solution is given by a proof, and A represents the existence of such a proof.31

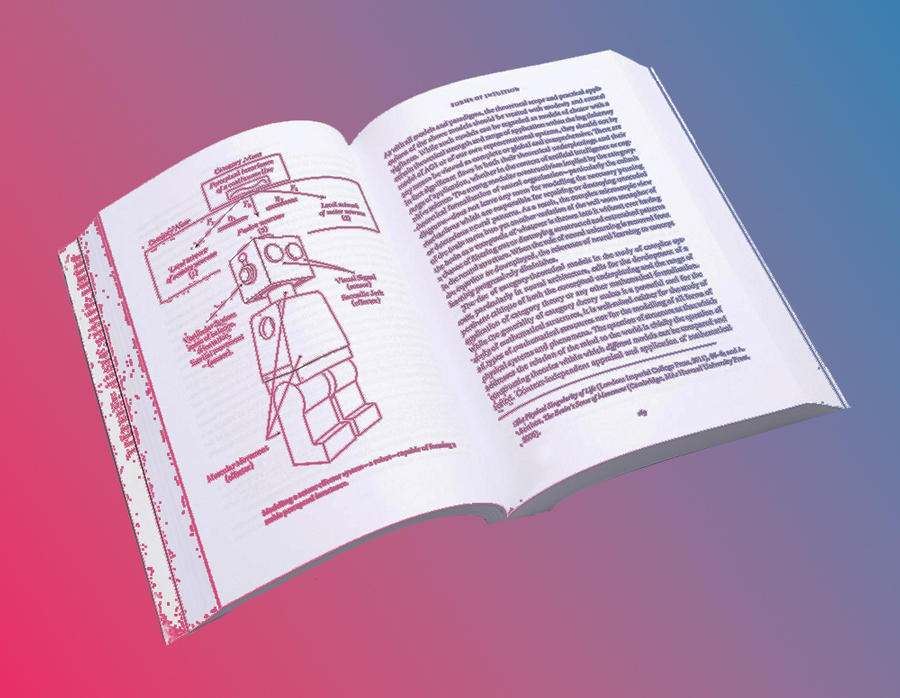

5. Interactive Schema of Meaning-as-Proof: In the universe of automata, the interactive schema of meaning-as-proof can be thought of as a toy meaning-dispensing machine. The machine consists of two agents interacting over a language C. “Inside this interactive machine, there are algorithms that obtain proof either through normalization or search.”32

Overall, Negarestani situates dependent type theory within a broader philosophical exploration of cognition, intelligence, and the nature of thought. The theory serves as a tool to understand the expressivity and structure of types, especially in the context of interactive systems and the nature of proofs.

NOTES

1Reza Negarestani, Intelligence and Spirit (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2018).

2Negarestani, Intelligence and Spirit, 1. Quoted material inside the citation: Lorenz Puntel, Structure and Being: A Theoretical Framework for a Systematic Philosophy (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008), 275.

3Ibid., 169-170.

4Ibid., 418-419.

5Ibid., 419.

6Ibid., 432.

7Ibid., 365-366.

8Ibid., 371-372.

9Ibid., 372-373.

10Ibid., 374-376.

11P. Wagner, Carnap’s Logical Syntax of Language (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 14.

12Negarestani, Intelligence and Spirit, 335.

13Ibid.

14Ibid.

15Ibid., 523-524.

16Ibid., 395.

17André W. Carus, “Sellars, Carnap and the Logical Space of Reasons,” in Carnap Brought Home: The View from Jena, eds. Steve Awodey and C Klein, (Chicago: Open Court, 2003).

18Negarestani, Intelligence and Spirit, 334.

19Ibid., 501-502.

20Ibid.

21Ibid., 457.

22Ibid., 342.

23Ibid., 464.

24Ibid.

25Ibid., 54.

26Ibid., 418.

27Ibid.

28Ibid.

29Ibid., 419.

30Ibid., footnote 419.

31Ibid., 417.

32Ibid., 361-362.