Five hundred million individuals tried to monetize their social media last year, according to a recent Linktree survey. As a lucky member of this esteemed group, I recently found myself surfing through the entrepreneurial side of TikTok, captivated by a video titled “How to make money with Chat GPT”. The clip tells you to go to AIVA.AI, which uses artificial intelligence to generate a series of automated musical compositions, and its money-making tip is simple: sell your (or AIVA’s?) automated music as “background” tracks to feature in video content made by other content creators.

The machine-assisted, algorithmic musical composition has a rich history, and AIVA is like an absurdist footnote to its many forebearers. These include the League of Automatic Composers, Yasunao Tone’s AI Deviation works, David Tudor’s Neural Synthesis works, Lars Holdhus’ TCF project, and Google’s Magenta division, to name just a few. One of the great innovators of artificial intelligence research, Alan Turing, also speculated whether AI might one day pick up a guitar, inspired by his conversations with the inventor of information theory: “[Claude] Shannon wants to feed not just data to a Brain, but cultural things! He wants to play music to it!”

In the entrepreneurial TikTok’s automation experiment, which is narrated with the gravity of a life-hack, the creator directs you to a royalty-free media library called Envato Elements, where you sign up to contribute as a producing artist. If you want “more alpha” in your free time, upload the automated compositions there and gain passive income. I actually completed four of the five steps before stumbling over the glaring problems that rendered this scheme less effortlessly lucrative than the creator suggests. I stopped what I was doing as the fog cleared and it became clear I was wasting my time. This video, among the ocean of online self-help, is just one of a billion by content creators shilling sketchy and dubious ways to make easy money, from crypto trading to Shopify dropshipping schemes to foreign exchange trading. For about three minutes, the creator had skilfully puppeteered my own desire for low-effort profit, recently aggravated by economic storm and stress. I caught myself hypnotized by the prospect of easy money; it was as if the clip had turned me into a mindless “bot.” Now I’m back.

§

Online content has, in effect, become profoundly homogenized. Everywhere you look – whether it’s on TikTok, Netflix, or Spotify – you’re hit by a torrential flood of sameness. Is this a new phenomenon? Of course not: popular culture has always aspired to predictability in the comforting form of repetition and standardization. Has the media landscape become more homogenized in, say, a post-Covid world, where corporate internet dynamics are infused with even greater leverage over the social body? It certainly seems like it. (Involuntary repetition, i.e. repetition compulsion, according to Freud: “…a principle powerful enough to overrule the pleasure principle, lending to certain aspects of the mind their daemonic character…”). Today we are haunted by our own painfully hard-to-shake repetition compulsions, taking form in the discomfiting physiological mandate to keep scrolling, and keep consuming. Attention, easily quantifiable with such widespread tools as Google Analytics, A/B testing, and eye-tracking software, makes itself available as a resource to be exploited by rabid disciplinarians, putting the emperor of “scientific management” and its obsession with economic efficiency in new clothes. Fortunately for platform capitalists, the homeostatic formal and stylistic patterns of contemporary online content consumption make attention easier to predict and manage.

Put simply, messages shared by “real humans” increasingly resemble those automated by bots. Many face-to-face encounters now resemble those with bots online as well, as friends and acquaintances parrot standardized talking points they have been instructed to recite by their preferred filter bubbles. The homogenization of cultural criticism – all too neatly categorized as either Condé Nast-style “radical” liberal orthodoxy or reactionary opportunism simplistically positioned as a rebellion against the Law of the former – follows the same pattern. These patterns resonate and coincide with the popularization of “NPC” (i.e. non-playable character, originating in the role-playing video game genre) as a derogatory term for real-life “normies”.

What we’re seeing here may be some symptom of the subjectivizing effects of “ideology.” In America, the “system” seems on the brink of ripping apart in numerous directions at once – if anything, it is decisively incoherent. Competing forms of ideology seem too strained by fragmentation to successfully interpellate subjects into a mono-universalist worldview. We are faced with what appears to be not a monolith but a many-faceted superstructure servicing a tense and shapeshifting info-war; a tactical detente which is objectively hard to understand by monitoring the ad-driven media environment available to us.

We can venture an axiom: if an ideology is successful, it transforms people into bots that (automatically) reproduce the talking points of filter bubbles. The affordances that a bot has for thinking, feeling, producing, and consuming are re-engineered for maximal utility by a given constellation of power. As Althusser describes the process of recruitment: “ideology ‘acts’ or ‘functions’ in such a way that it ‘recruits’ subjects among the individuals (it recruits them all), or ‘transforms’ the individuals into subjects (it transforms them all) by that very precise operation which I have called interpellation.” There’s an overarching sense of sociopolitical gridlock in part because the average person has been interpellated as a bot for several different ideologies at once; wires are getting crossed. A bot is what Deleuze calls the “dividual”: “We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair. Individuals have become ‘dividuals,’ and masses, samples, data, markets, or ‘banks.’” In the midst of our chimerical media landscape, ideology functions in such a way that a dividual is the de facto host for many bots – which uneasily coexist as a simultaneous, at times contradictory series of doubles, reflections, and iterations. Kittler: “To see doubles as a ‘phantom of our own ego,’ one must, as a matter of principle, conceal the strategies by means of which crafty others have produced the phantom.”

The other day I was scrolling on TikTok and encountered a short clip of a song with the following lyric: “If you get killed in a school shooting you’re a fuckin’ bot.” Later I looked it up and it’s a song called “Punch Anthem” by some guy called Punchmade Dev, who I know nothing about. It tests the limits of irony: saying something untrue while articulating it as if it were true. He taunts the listener with his delivery. The claim seems designed to resist interpretation: you’re not supposed to decode it, you’re supposed to feel the sheer improbability of its recitation. What the artists means here is in the final instance unimportant, and so as a piece of information it emblematizes certain aspects of Claude Shannon’s formative work in the field of information theory, which he pioneered while working at Bell labs, improving the quality and reliability of transmissions across copper telephone lines. He was concerned with the mathematical likelihood of getting a message from one place to another and he did not care about what it signified; he is brazen enough to propose a signification-agnostic concept of information. For Shannon and the networks he engineered, the informational content of a message is evaluated not by what it means but by the likelihood of the message’s actual occurrence. Shannon’s work displaced the notion of a communicated idea with new emphasis put on the probability of the informational event. (In light of this theory, Punchmade Dev’s lyric may be read as an incredibly improbable claim.)

In “Punch Anthem,” “bot” is clearly not a value-neutral term. His conception of a bot describes a being that is not only weak, but, more importantly, strictly incapable of mustering the superheroic strength required for actualizing low-probability outcomes: the bot can only generate content with low informational value, much like the AIVA.AI composition tool, which creates music far more suited for formulaic marketing materials than serious art. Bots are incapable of doing anything remarkable, for example, surviving a school shooting.

Punchmade Dev raps about the fate of bots during a time of widespread anxiety about artificial intelligence. The social fabric has come alive with fear and enthusiasm at the prospect of being replaced in our jobs, in our relationships, and in our bedrooms by sentient assemblages of electrical currents. Because of its absolute reliance on robust datasets, emergent AI feeds upon all of us, on media artifacts of human culture in the most general sense – as Shannon foretold in his conversations with Turing – and yet it has no material allegiance to the average person, the average bot. In the midst of all this, humanity is undergoing a process of rapid re-engineering, as if fabricated in the image of bots while bots lay claim to the most basic of human activities. Too many huge companies to name – from Microsoft to Google and Shopify – have already integrated features utilizing large-language models (LLMs, e.g. something along the lines of Chat-GPT), and Buzzfeed is already publishing full-length, AI-generated articles.

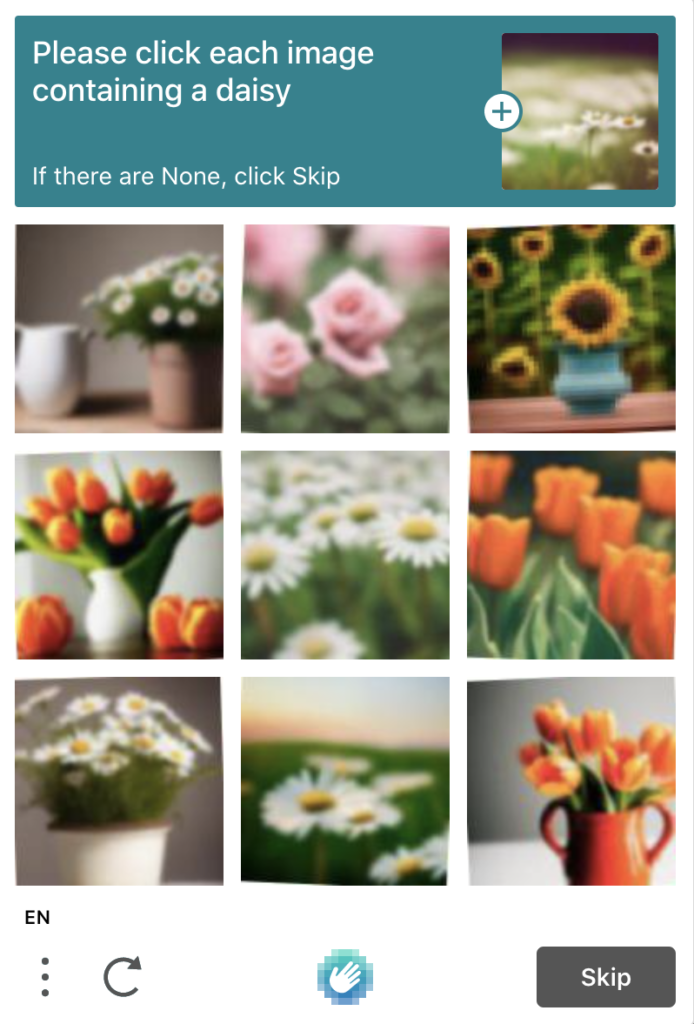

Endlessly respawning sexbots pollute dating apps and Instagram story likes in order to bait users into who knows what; meanwhile, those same users must constantly “prove they are human” through CAPTCHAs – which are in turn used to further refine AI – in order to access basic internet infrastructure. For a long time, the images in CAPTCHAs used to look like they were culled from suburban junkspace on Google Maps. Recently, I saw one that solely consisted of AI-generated images for the first time, like some NFT collection of the shittiest floral still lifes you have ever seen in your life. A gatekeeper has never taken on such a strange visage: I used to train it to see like me, now it is training me to see like it. Ever since the big bang, no daisy on earth has ever looked quite like these.

What particular characteristic or achievement would meet the criteria for AI to be considered truly “intelligent”? One well-known benchmark for investigating this thorny question is the Turing Test, also known as the “imitation game,” which evaluates a machine’s ability to have a natural language conversation in such a way that is totally indistinguishable from a 100% organic human correspondent. (It’s interesting to note that in this scenario a machine is imagined and positioned as an interlocutor, a double, when it could be literally anything else – is anthropomorphization a repetition compulsion?) Based on the homogenous media environment described above, though, one can’t help but wonder whether AI is really the bot we should be most worried about at the moment. Given the way things are going, are we so sure, in 2023, that the average content creator can even pass a Turing Test? In December, @heylujan, the U.S Army “psyop” E-Girl, posted an ironically self-reflexive meme exuding delight through the vernacular of dissimulation-as-interpellation made possible through bot-praxis.

It’s almost as if Hailey Lujan wants you to think she’s a bot; on LinkedIn, her job title is “Psychological Operations Specialist at US Army.” She revels in the mutability afforded by the form, playing upon unconscious tensions in the popular imaginary relating as much to the humanoid AI hijinx of Ex Machina (2014) as the specter of Russian disinformation accounts and their supposed effect on the 2016 presidential election. Here’s Kittler again: “Cinematic doubles demonstrate what happens to people who step into the firing line of technical media.” His claim resonates with Lujan’s content-being in more ways than one. Much like Althusser’s theory of the ideological construction of the subject, the double is always mediated by history. Roughly 110 years ago, in his essay on the uncanny, Freud describes an encounter with his own double on a train; he “thoroughly disliked” the figure he encountered in a reflection before realizing it was himself. In Romantic literature, the figure of the double realizes the subject’s repressed desires, dooming it to failure, turning its world upside-down. By contrast, bot-existence today is a source of comfort, offering paradisiacal respite from the Real’s irresolvable complexity. It’s nice to have autocorrect lead the way when you’ve forgotten how to spell.

What’s the difference between a person and a bot? The very question indexes a sectarian conflict, and even an undergraduate barely familiar with Descartes knows that it is fallacious to take the figure of the human as somehow given. Indeed, only a bot, propagandist, or salesperson would argue otherwise. Who better than ChatGPT to shed some much-needed light on the subject? Piecing together its statements from a strategic blend of high and lower-probability words in order to simulate “creativity” – because a conversationalist making only the most predictable statements gets boring quickly – it offers: “Humans have the ability to understand and interpret language in a way that is nuanced and contextual, and we are able to express ourselves in a way that conveys emotion, intention, and personality.” Given that the semantic texture of this response contradicted the terms of its argument, I replied that this wasn’t a convincing enough answer. It apologized and grasped further into the recesses of its dataset: “It is possible that some people may exhibit behaviors that are repetitive, predictable, or robotic in nature, but this is often the result of conditioning or other psychological factors, rather than an inherent characteristic of being human.” We can infer one final difference between humans and bots: people are afraid of complexity, of the Real, whereas bots avoid it because they don’t know any better. Not yet, anyway. At the launch of GPT-4, OpenAI’s founder Greg Brockman weighed in on the axiomatic integrity of the new model. “It’s not perfect,” he said, “but neither are you.”