INTRODUCTION

The following analyses are hypothetical entries into Karen Pinkus’ Fuel: A Speculative Dictionary, a dictionary which itself ought to be read as a work in perpetual progress.[1] Drawing upon Pinkus’ work—cross-referencing, if you will—I want to introduce two entries (themselves, necessarily works in perpetual progress) into Pinkus’ registry; one site-specific, one ‘generic’: “Carrie Furnace” and “Iron.” The goal of these entries will be to further explore the concept of fuel from a human and inhuman perspective. Indeed, the entry on “Carrie Furnace” will be based on my own field research at the location as well as the 2010 documentary, History to Go: The Carrie Furnaces. The entry on “Iron” will attempt to weave three threads together in a perverse French braid, looking at antique theories of metallogenesis, contemporary theories of nucleosynthesis, and a situation of iron as a stellar gift par excellence. While dealing, admittedly tangentially, with the question of subjectivity, my goal in the following is to blur the line between subjectivity à la human consciousness and ferric materiality.

CARRIE FURNACE[2]

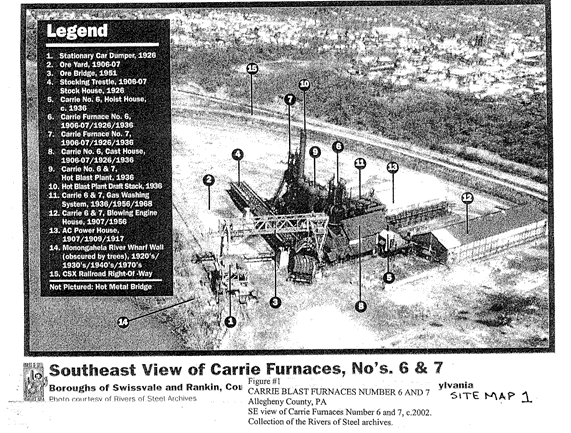

As the industrial revolution raged in England, the United States of the 1800s lagged behind. Despite being a major hotspot for industrial development, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania didn’t have a blast furnace—a cauldron for separating iron ore (SEE ALSO IRON) from the ‘useless’ rock around it—until 1859. Racing to keep up, the city, located conveniently along river trade routes and in an area rich with natural resources, attracted the attention of investors. Joseph Brown, H.C. & W.C. Fownes, and William Clark saw an opportunity and founded the Carrie Furnace Company in the early 1880s, after which they purchased land just outside of Pittsburgh along the Monongahela River to build an iron mill. Appropriating a failed blast furnace from Port Washington, Ohio, the Carrie Furnace Company ‘blew in’ their first furnace in 1884, with iron production following shortly thereafter.

Figure 1: Site Map

Figure 1: Site Map

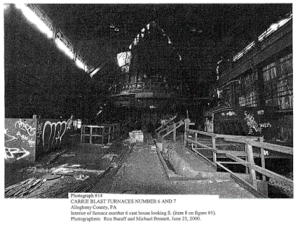

Figure 2: Blast Furnace No. 6

Figure 2: Blast Furnace No. 6

In blast furnaces, limestone, hematite (iron ore), and coke are mixed in an infernal reaction. The coke—specially treated coal with a higher burn temperature and lower sulphur content—is mixed in with hematite and limestone and dropped into the top of the blast furnaces via skip hoists (Fig. 3). After that, hot, pressurized air from the hot stoves (Fig. 4) is forced into the furnace to heat the coke to 2,800°F (1,500°C), ultimately igniting it.

Figure 3: Skip Hoists on Furnace 7

Figure 3: Skip Hoists on Furnace 7

Figure 4: Hot Stoves Flanked by Furnaces 6 (right) and 7 (off-camera left)

Figure 4: Hot Stoves Flanked by Furnaces 6 (right) and 7 (off-camera left)

The intense temperatures and pressures—violence recapitulating not only the violence of stellar fusion, but the horrors of mining—rip pure iron from sand, separated elements forming carbon di- and monoxide, leaving behind superheated molten iron and ‘useless’ slag. The temperatures in the ‘maw’ of the furnace (Figs. 5 & 6), where iron was tapped and would “flow like water,” were so intense that street clothes were liable to ignite. Ron Gault, former laborer, aptly noted that working in a blast furnace was like working with “a controlled volcano”; the violence and power of geological forces were harnessed in a singular area.

Figure 5: The ‘Maw’ of Furnace 6; Torpedo Rail Car in Lower Middle

Figure 5: The ‘Maw’ of Furnace 6; Torpedo Rail Car in Lower Middle

Figure 6: The ‘Maw’

Figure 6: The ‘Maw’

What was unique about the Carrie Furnace pre-1900s is that it was a merchant furnace, operating independently of any of the major iron and steel conglomerates of the era. Instead of being obligated to sell its iron to one company, Carrie operated on the open market. Despite this financial freedom and the addition of a second furnace in 1889, however, the mill was struggling to keep up with competing operations that integrated both iron smelting and steel production. Given that, Brown, the Fownes, and Clark decided to sell the mill.

In 1898, Andrew Carnegie purchased the Carrie Furnaces and integrated them with his Homestead Steel Mill just south of the Monongahela. Where formerly the iron produced at Carrie was cast as pig iron (Fig. 7) only to be reheated later at a steel mill, Carnegie built a bridge across the river connecting the two mills so that molten iron could be transported from one site to another in specialized ‘torpedo train cars’ (Fig. 5).

Figure 7: Pig iron in upper center. Also shown, hematite (iron ore), limestone, and coke.

Figure 7: Pig iron in upper center. Also shown, hematite (iron ore), limestone, and coke.

After adding more furnaces and diversifying his bonds, Carnegie sold J.P. Morgan all his steel interests, leading to the creation of U.S. Steel, whose signifiers still mark the site to this day (Figs. 8 & 9). The mill worked throughout the 1900s, expanding and smelting the iron that would form the steel which served as the backbone for the Empire State Building, among others. As demand declined in the 1970s, the furnaces, of which there were seven in total, began shutting down, and in 1982, Carrie breathed her last fiery breath.

Figure 8: U.S. Steel’s logo on the AC Powerhouse

Figure 8: U.S. Steel’s logo on the AC Powerhouse

Figure 9: A U.S. Steel Sign Leaning Against the AC Powerhouse

Figure 9: A U.S. Steel Sign Leaning Against the AC Powerhouse

With only furnaces 6 and 7 standing, the site lay dormant until 2006, when both furnaces were classified as National Historic Landmarks and the Rivers of Steel Heritage Corporation began giving tours. In a turn of fate, however, Carrie was far from finished generating revenue. Where once chemical reactions were the catalysts for capitalistic growth, a new reaction took its place. Building upon the ‘heritage of the area,’ Rivers of Steel began to transition from mineral capital to cultural capital as a “new extraction process,” that of exploring the plant, mining it for knowledge, took over.[3] As Robin Mackay notes of mining tours:

This time, capital creates not a chemical but a semiotic landscape, turning it into a series of signs or images to be mined and consumed. In this way, the waste products of the industrial age are reprocessed, extraction begins anew, voids are apparently filled, and deads become undead.[4]

Figure 10: Author Mentally Preparing for Tour

Figure 10: Author Mentally Preparing for Tour

Figure 11: Author Decompressing/Decomposing Post-Tour

Figure 11: Author Decompressing/Decomposing Post-Tour

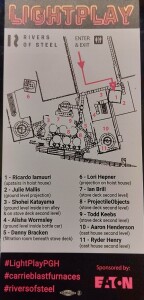

Indeed, such is the fate of Carrie, which not only hosts tours nearly year-round but has commodified art itself leading to metal working classes, art shows, and their famous “lightplay” light shows (Fig. 12). Not only does the sun provide us with “[t]he origin and essence of our wealth,”[5] and not only does stellar nucleosynthesis provide us with riches to extract from the earth to continue, and indeed, accelerate, our path of industrialization, but the remnants of the remnants of the celestial play of energy provides us with yet another form of wealth generation. Under capitalism, nothing truly goes to waste.

Figure 12: Lightplay Map

Figure 12: Lightplay Map

COAL

See Pinkus, 48-55.

CTHELLL

“Earth’s iron ocean, comprising one third of terrestrial mass, approximately three thousand km below the surface. Intensive megamolecule.”[6]

HYDROGEN

See Pinkus, 67–68.

IRON

Daniel Charles Barker once noted of the study of geo-movement, “[f]ast forward seismology and you hear the earth scream.”[7] Geological experiments abound, and attempts to probe and penetrate the earth came to a stunning explosion in 1928 with two events separated by three thousand miles and one month.

In June of 1928, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s character, Professor George Edward Challenger, FRS, MD, DSc, set out to prove a unique, if admittedly idiosyncratic theory: “that the world upon which we live is itself a living organism,” an organism Challenger believed was “endowed […] with a circulation, a respiration, and a nervous system of its own.”[8] A lunatic to some, a genius to others, Challenger asserted that the body of the earth was similar to a sea-urchin—the “echinus is a model, a prototype, of the world.”[9] When questioned about the numerous oddities of his theory, namely the question of nourishment, Challenger responded that similar to the echinus, surrounded by water, the body of the earth was surrounded by a nourishing ether (SEE ALSO CTHELLL).

Proposing to make the earth aware of the creatures on its surface, Challenger intended to “pierce [the earth’s] horny hide” with a drill in the North of England.[10] Needless to say, with his vast riches and access to ‘manpower,’ Challenger did indeed penetrate the earth. In June 1928, once Challenger brutally awoke Mother Earth in a quasi-Hegelian act of forced recognition, he was assaulted by “a howl in which pain, anger, menace, and the outraged majesty of Nature all blended into one hideous shriek.”[11] Setting off a chain reaction of “intense Plutonic indignation”[12] around the world and across time, we enter the second part of our story.

May 1928, 39.9348°N 80.0737°W, North of Mather, Pennsylvania, USA: Mather Mine, a relatively unremarkable mine built in 1917 to extract coal (SEE ALSO COAL)—fossilized sunlight—experienced a visceral precognition of Challenger’s experiment that would occur one month later. Striking out in blind pain—no doubt fearful of what was to come, like a bad dream—the mine exploded.[13] Crumbled bits of coal mixed with gases floating throughout the mineshafts created the perfect storm for Mother Earth to redirect her intensive flows of energy. Where mining can be seen as a controlled “geocosmic pressure-release valve,” the uninhibited flow of gas and dust waiting for one small spark could be seen as Mother Earth proverbially ‘blowing off steam’; screaming, as Challenger would make her do.[14] The blast of sheer energy, a culmination of geocosmic repression and stellar abundance, tore through the mineshafts on May 19th at 4:07pm, leaving 195 people dead in the wake of the explosion.[15] If Challenger was to be verbally assaulted a month later, the miners at Mather suffered a veritable temper tantrum. “Fast forward seismology and you hear the earth scream.”[16]

Rewind.

“IN the beginning God created heavens and the earth. The earth was without form, and void; and darkness was on the face of the deep.” (Genesis 1:1–2) He created within the earth, a prime metal, a metal from which all other metals spawned; a metal whose original name has long been lost but is now called Gur (or Ghur, or Guhr, or Bur).[17] The metals we take from the womb of the earth “do not grow in the Earth, but were at once created of God,” “evidence of God’s generosity.”[18]

To inspire the Bohemian miners of 16th century Joachimsthal (in the modern-day Czech Republic), Johannes Mathesius, Lutheran minister and author of the elusive Sarepta,[19] held ‘sermons on the mount.’[20] Urging struggling miners forward and affirming that they “used ‘not to work in vain’ when searching for ores,” Mathesius noted the gift of Gur, a prime metal from which all other metals flowed.[21] Gur was “a buttermilk-look substance” “placed in the interior of the earth,” “like a child in the maternal womb,” “by the Creator in an ‘incomplete’ form.”[22] The earth became a body to be explored. Gur, extracted from the ‘womb,’ the ‘veins,’ the body of the earth was a “sulphur-mercurial matter” which, when subject to different proportions of “sulphur and mercury,” resulted in the transmutation into “the known metals.”[23]

This sulphur-mercury theory, a theory which drove ever more miners in search of the prime matter—they ought “to rejoice that God has his workplace not only in the heavens and upon the surface of the Earth, but with its cold, dark, subterranean depths as well[!]”[24]—was recapitulated in the 17th century by Yorkshirean schoolmaster, John Webster, in his expanded treatise, Metallographia.[25]

For Webster, Gur, when proportionally correct, yields two types of iron. The richest was pure, “Native Iron.” What Webster calls “Ralandus” is pure iron found in a “Vein or Mine,” in the “sand of the Rivers,” or an iron of “liver colour” found in a place called “Gifhubeliah.”[26] Miners coming across such ores, either in Germany or Norway or England, were greeted with, if not “liver colour[ed],” a multitude of different colored ores to be removed.[27] Such iron, once excised, became fuel for the great war machines of the 1600s, being made into “bullets for Cannons.”[28] “The LORD is a man of war; the LORD is His name.” (Exodus 15:3)

The record hits a scratch. Jump.

1931. Attempting to answer questions raised by British physicist James Jeans, a middle-aged Belgian Priest named Georges Lemaître proposed, following his explanation of an expanding universe, what he called a universal, “primeval atom.”[29] Answering a hypothetical question posed to an “infallible oracle” (no doubt, the Oracle at Delphi) wherein she is asked, “Has the universe ever been at rest, or did the expansion start from the beginning?” Lemaître argued that if the universe is expanding, then there must have been a time when it was smaller. Indeed, winding the clock back, all mass in the universe “would exist in the form of a unique atom.” While “not strictly zero,” such a compact state would produce the entire universe—in a chilling affinity with theories of Gur—through “the disintegration of this primeval atom.” Lemaître’s thesis was arguably the first articulation of the Big Bang theory of the universe.[30]

While the theory would go through numerous iterations over the next 90 years (the nuances of which are best saved for someone more qualified),[31] the current commonly accepted age of the universe is 13.8 billion years, and from Lemaître’s primeval atom, we witness the world today.[32] To keep up with the teachings of Johannes Mathesius and other sulphur-mercury theorists of metallogenesis, ‘proper’ scientists needed an explanation for the formation of the elements, however.

Contemporary cosmology, to explain the formation of the lighter elements (hydrogen up to lithium), resorts to so-called ‘Big Bang Nucleosynthesis’ (BBN). As per our understanding, in convergence with Lemaître’s primeval atom, “[t]he Universe was born in a ‘big bang’ at a moment when the density and the temperature were (almost) infinite, in the most symmetric state.”[33] “[R]adiation dominated” and in a very small space, the density of matter and energy was so extremely high such that a few minutes after the proverbial ‘bang,’ “protons and neutrons began to combine into atomic nuclei producing hydrogen, helium and a trace of lithium” (SEE ALSO HYDROGEN AND LITHIUM).[34] High speed collisions between matter in this very early, hot, and expanding era of the universe resulted in “a race between the various nuclear reactions on the one hand and the inevitable cooling that accompanies the expansion of the universe on the other” which in turn favored the creation, via fusion, of the aforementioned lighter elements.[35] As the universe expanded, the temperature and density of matter “became too low for further nucleosynthesis,” and the universe expanded with no stars.[36]

From then (fast forward a couple hundred million years), gravity began to pull massive clouds of hydrogen and helium together causing stars to form. Our story now takes an interesting and violent turn. Population III stars, the first stars made from the created hydrogen and helium, were massive and, when they died in spectacular explosions, seeded the cosmos with the material for new, longer lasting stars. These new stars, massive and long-lived, eventually fused all their primary fuel—hydrogen—and began to “burn helium to make carbon, oxygen and a host of heavier elements.” The story takes a ferric turn here.[37] As these massive stars died, they underwent internal combustion and collapse, with gravity compressing repelling elements closer and closer until, in an event one would die to see, the star explodes in a type Ia supernova, further smashing atoms together and creating iron, along with heavier elements.[38]

Spewed into the cosmic void, these “iron bullets” littered interstellar space and seeded the early solar system with what would become earth’s metallic body.[39] Our “protoplanetary disk,” rotating around a newborn star, underwent a so-called “‘Iron Catastrophe’” wherein “a sudden sinking of matter into a dense metallic core” calcified and stratified the earth, locking the remnants of intense stellar violence under a traumatized crust.[40] “[T]he molten core was buried within a crustal shell, producing an insulated reservoir of primal exogeneous trauma.”[41]

When Challenger penetrated the earth’s crust in an effort to violently awaken the Mother’s inner organism, the scream he heard, the explosion the miners at Mather felt, and the cataclysms that followed were Mother Earth “voicing her indignation”; a deep trauma being released.[42]

Stop.

In congruence with Lemaître’s publications, the sun of 1931 was active, shitting out a text by a different Georges (SEE ALSO SUN). Deeply connected to Plutonic theory, Georges Bataille published “The Solar Anus,” a work that, while not merely arousing, speaks across (deep) (penetrative) time to reaffirm the insights of Freud and portend the work of Barker: life is a recapitulation of energetic expenditure. For Bataille, this is obvious: “It is clear that the world is purely parodic, in other words, that each thing seen is the parody of another, or is the same thing in a deceptive form.”[43]

The motion of bodies—both celestial and terrestrial—operate around activity, “rotation and sexual movement.”[44] Both give life, as well as death. The earth spins, the days go by, organisms orgasm, and the cycle continues. Bataille contrasts humans to vegetation. The latter are heliomanic: “[v]egetation is uniformly directed towards the sun,” while the former are heliophobic, traumatized: humans “necessarily avert their eyes.”[45] We gaze downward, into the earth, not knowing that “[t]he descent into the body of the earth corresponds to a regression through geocosmic time.”[46]

Indeed, for Bataille, despite our heliophobia, the sun is crucial for life. “Solar energy is the source of life’s exuberant development.” The sun, and in turn, other celestial bodies—stars as such—are the ultimate givers. The sun kills itself, burns up its body and shines its “indecent solar rays” upon the terrestrial surface “without ever receiving.” It is the wellspring of life that will, one day, kill us.[47]

Despite Bataille’s attempt to formalize a solar economy built around the life of the sun, he neglects its death. His work is profound in that it speaks to our usage of current energy generated by fusion within the heart of the sun, but it neglects the remnants of the sun’s stellar kin. “Distant stars lapse into death and yet their desiccated corpses are still alight in Cthellic astronomy.”[48]

The stars that make up our galaxy—our celestial neighbors—are not merely far away in space, but distant in time.[49] Their ‘existence’—indeed, they may not exist ‘anymore’—speaks to a time anterior humans, and our astronomical observations are more correctly classified as temporal observations. Every astronomer is an historian. While Chakrabarty wants to humanize history, asserting that the very discipline “exists on the assumption that our past, present, and future are connected by a certain continuity of human experience,” history needn’t be bound to the anthropoid.[50] Admittedly, I’m doing Chakrabarty dirty. He doesn’t strictly anthropomorphize history. In linking history to climate change, Chakrabarty argues that human history—what he defines (through others) as “the story of human affairs”—is, at this point in time, indistinguishable from natural history.[51] Our deep entanglement with the earth to the point of accidental geoengineering has brought with it a new epoch, one in which we are a geological force, so-called “geological agents.”[52]

Nevertheless, this entanglement still privileges the human and brings time itself under our purview. It is here that we take what we need from Chakrabarty, namely that humans are “geological agents,” and then discard him. We return, parodically/periodically, to le temps sans l’humain; deep time. Equally hard to define as it is to comprehend, deep time can most ‘easily’ be spoken of as “a temporality [that] accommodates everything from the fading memory of the present […] to the origin of the universe.”[53] Operating on unimaginably large and long scales, deep time is best understood by looking at both the ground beneath our feet and the stars above our heads. Not only is the dirt upon which we stand made up of the remnants of nuclear fusion in the hearts of giant stars, but the stars above our heads are producing new worlds as we speak. It is here that we return to our ferocious friend, iron.

While it’s easy to look at the stars and grasp that they are deeply far away—both temporally and spatially—it’s more difficult to situate such distance beneath our feet. As we dig, however, we are not only venturing into earth’s past, but the past of the cosmos. Extracting coal, iron ore, limestone, and other minerals, we are extracting, in turn, solar rays trapped in a hardy, material form, bile from dying stars countless (light)years (away)ago, the results of a geological pressure-cooker. While coal and limestone interest us to different degrees (SEE ALSO CARRIE FURNACE), iron is what we will focus on.

Iron is a fuel any way you slice it. From the Latin ‘focus’ = hearth, to French ‘fouaille’ = fire, fuel provides energy. The death knell, the fuel of their demise, once iron starts to be forged in a star’s heart, there is no going back. The iron is a fuel inhibiting the star’s growth such that it “falls into an irreversible process whereby everything that is in its core […] turn[s] to iron” as residual carbon begins to fuse wherever else it can, making different metals (e.g., nickel and zinc).[54] From there, “these metal isotopes are spewed forth in the last hours and minutes of the dying star as both its matricidal offspring and post-mortem relics.” Crucially, while the star has ‘finished’ giving us cosmic rays, these “post-mortem relics” act as the ultimate form of energy in Bataille’s solar economy.[55] As Negarestani notes, “[t]he iron relic [serves as] the materialised personification of stellar death par excellence.”[56] Not only are they given to us with no expectation of repayment, they are given as deathly gifts. The screaming mother, being “asphyxiate[d]” from the inside, vomits up a final gift for us to use: an element with “the most tightly bound nucleus in nature” that we extract to, coincidentally, fuel further extraction.[57]

Iron fuels not only the death of stars, but the growth of industrialization. We use the iron extracted from the earth—iron that has existed before humans (if there ever was an arche-fossil, iron is it)[58]—to upgrade our equipment and push us deeper into the geologic unknown. Indeed, iron, perhaps more so than coal, occupies a unique temporal standing. Not quite a hyperstition, its extraction not only paves the way for future extraction, but it also accelerates it. As we draw iron from the earth, the iron acts through us—a parasitic agent desiring to unearth more of itself—to promote, via its usage, ever deeper and more efficient modes of extraction.

Moynihan: “There’s an interesting loop here: our deep past seems to be determining and conditioning our future in advance. Historically, the more we mine, the more we are compelled to mine (and the better we are able to do so).”[59]

LITHIUM

See Pinkus, 70.

SUN

See Pinkus, 91–93. The history of the question, “How [does] the sun shine?” is an interesting one in and of itself.[60]

–

Notes

[1.] Karen Pinkus, Fuel: A Speculative Dictionary (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

[2.] All information gathered from History to Go: The Carrie Furnaces, produced by Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, 2010. Black and white images courtesy of National Historic Landmark Nomination: Carrie Blast Furnaces Number 6 and 7, prepared by Michael Bennett, 2006. (https://riversofsteel.com/_uploads/files/CarrieLandmarkNominationFinal.pdf)

[3.] Robin Mackay, “Underground Adventure,” in Hydroplutonic Kernow, ed., R. Mackay, 161–171 (Falmouth, UK: Urbanomic Media Ltd., 2020): 168.

[4.] Mackay, “Underground Adventure,” 169.

[5.] Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share, Vol. 1, trans., R. Hurley (New York, NY: Zone Books, 1991), 28.

[6.] CCRU, “Appendix 1: CCRU Glossary,” in Writings: 1997-2003 (Falmouth, UK: Urbanomic Media Ltd., 2017): (:)(::)[1]:: – :[2]:(::(:)), (:::)(:::) [357-370, 361]. See also, CCRU, “Tick Delirium,” op. cit., (::(:)(:)) [151]; CCRU, “Barker Speaks: The CCRU Interview with Professor D.C. Barker,” in Abstract Culture: Digital Hyperstition (London, UK: CCRU, 1999): 2–8, 4-5.

[7.] CCRU, “Barker Speaks,” 5.

[8.] Arthur Conan Doyle, “When the World Screamed,” in The Professor Challenger Stories (London, UK: John Murray, 1963): 547–577, 553.

[9.] Doyle, “When the World Screamed,” 554.

[10.] Ibid., 555.

[11.] Ibid., 575.

[12.] Ibid., 577.

[13.] Cf. Eric Wargo, Time Loops: Precognition, Retrocausation, and the Unconscious (Anomalist Books, 2018).

[14.] Robin Mackay and Thomas Moynihan, “‘But It’s Only Late If…’: A Belated Anticipation of Hydroplutonic Kernow,” in Hydroplutonic Kernow, op. cit., 1–29: 18.

[15.] G.S. MoCaa and H.C. Howarth, Final Report on Mather Mine Explosion Pickands-Mather and Company Mather, Pennsylvania May 19, 1928 (archived report) (https://usminedisasters.miningquiz.com/saxsewell/05-19-1928_Mather.pdf)

[16.] CCRU, “Barker Speaks,” 5.

[17.] Ana Maria Alfonso-Goldfarb and Marcia H.M. Ferraz, “Gur, Ghur, Guhr or Bur? The quest for a metalliferous prime matter in early modern times,” The British Journal for the History of Science Vol. 46, No. 1 (2013): 23–37, 24.

[18.] John Webster, Metallographia, Or an History Of Metals (London, UK: A.C. for Walter Kettilby, 1671), 40; John Norris, “The providence of mineral generation in the sermons of Johann Mathesius (1504–1565),” in Geology and Religion: A History of Harmony and Hostility, ed., M. Kölbl-Ebert, 37–40 (London, UK: Geological Society Of London, 2009): 38. Cf. John Norris, “Early Theories of Aqueous Mineral Genesis in the Sixteenth Century,” Ambix Vol. 54, No. 1 (2013): 69–86.

[19.] Johann Mathesius, Sarepta oder Berg-Postill sampt der Jochimssthalischen kurtzen Chroniken (Nürnberg, DE, 1564).

[20.] Alfonso-Goldfarb and Ferraz, “Gur, Ghur, Guhr or Bur?” 25; We can see a similar theologizing of mining in the 1700s at Gwennap Pit in Cornwall, cf. Paul Chaney and Robin Mackay, “Gwennap Pit: From Subsidence to Sanctification,” in Hydroplutonic Kernow, op. cit., 107–116.

[21.] Alfonso-Goldfarb and Ferraz, “Gur, Ghur, Guhr or Bur?” 25.

[22.] Ibid.

[23.] Ibid., 26; Norris, “The providence of mineral generation in the sermons of Johann Mathesius (1504–1565),” 38.

[24.] Ibid.

[25.] Full title: Metallographia, Or an History Of Metals. Wherein is Declared the signs of the Ores and Minerals both before and after digging, the causes and manner of their generations, their kinds, sorts, and differences; with the description of sundry new Metals, or Semi-Metals, and many other things pertaining to Mineral knowledge. As also, The handling and shewing of their Vegetability, and the discussion of the most difficult questions belonging to Mystical Chymistry, as of the Philosophers Gold, their Mercury, and the Liquor Alkahest, Aurum potabile, and such like. Gathered forth of the most approved Authors that have written in Greek, Latin or High-Dutch. With some Observations and Discoveries of the Author himself.

[26.] Webster, Metallographia, 266. What is this place? Unknown.

[27.] Ibid.

[28.] Ibid., 267.

[29.] Georges Lemaître’s first explanation of an expanding universe can be read, “A homogeneous universe of constant mass and increasing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extra-galactic nebulae,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 91 (March 1931): 483–490; Georges Lemaître, “Contributions to a British Association Discussion on the Evolution of the Universe,” Nature Vol. 128 (October 1931): 704–706, 706.

[30.] Lemaître, “Contributions to a British Association Discussion on the Evolution of the Universe,” 706.

[31.] Cf. George Gamow, “The Evolution of the Universe,” Nature Vol. 162 (October 1948): 680–682.

[32.] Sabrina Stierwalt, “How Old Is the Universe?” on Scientific American, published January 10, 2018. Accessed December 16, 2020. (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-old-is-the-universe/)

[33.] Elisabeth Vangioni and Michel Cassé, “Cosmic origin of the chemical elements rarety in nuclear astrophysics,” Frontiers in Life Science Vol. 10, No. 1 (2018): 84–97, 86.

[34.] Richard Cyburt, Brian Fields, Keith Olive, Tsung-Han Yeh, “Big Bang Nucleosynthesis: 2015,” arXiv (2015): 1–50: 6; Vangioni and Cassé, “Cosmic origin of the chemical elements rarety in nuclear astrophysics,” 86.

[35.] Cyburt et al., “Big Bang Nucleosynthesis: 2015,” 6; Achim Weiss, “Big Bang Nucleosynthesis: Cooking up the first light elements,” on Einstein-Online, published April 28, 2006, accessed December 17, 2020. (https://web.archive.org/web/20070208212247/http://www.einstein-online.info/en/spotlights/BBN/index.html); Cf. George Gamow, “The Origin of Elements and the Separation of Galaxies,” Physical Review Vol. 74, No. 4 (1948): 505–506.

[36.] Vangioni and Cassé, “Cosmic origin of the chemical elements rarety in nuclear astrophysics,” 86.

[37.] Ibid., 93–94.

[38.] Eli Dwek, “Iron: A Key Element for Understanding the Origin and Evolution of Interstellar Dust,” The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 825, No. 2 (2016): 1–6, 1–2.

[39.] Danny Tsebrenko and Noam Soker, “Type Ia Supernova Remnants: Shaping by Iron Bullets,” arXiv (2015): 1–6.

[40.] Robin Mackay, “A Brief History of Geotrauma,” in Leper Creativity: Cyclonopedia Symposium, ed., E. Keller, N. Masciandaro, and E. Thacker, 1–37 (New York, NY: Punctum Books, 2012), 18.

[41.] CCRU, “Barker Speaks,” 4.

[42.] Doyle, “When the World Screamed,” 577.

[43.] Georges Bataille, “The Solar Anus,” in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, trans., A. Stoekl, C. Lovitt, and D.M. Leslie Jr., 5–9 (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 5.

[44.] Bataille, “Solar Anus,” 6.

[45.] Ibid., 8.

[46.] CCRU, “Barker Speaks,” 4.

[47.] Bataille, The Accursed Share, 28; Bataille, “Solar Anus,” 9; Bataille, The Accursed Share, 28.

[48.] INANE DREAMZ, “Lithospheric Poetry,” Plutonics: A Journal of Non-Standard Theory Vol. 13 (2020): 9–22, 21.

[49.] One could derive this insight solely from a rudimentary understanding of Einstein. If space and time are intimately bound together, physical location must be inextricably linked with temporal location.

[50.] Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry Vol. 34 (2009): 197–222, 197. Emphasis my own.

[51.] Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History,” 201.

[52.] Ibid., 207.

[53.] David Wood, Deep Time, Dark Times: On Being Geologically Human (New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2018), 3.

[54.] Reza Negarestani, “Revolution Goes Ferric: Notes on the Deeper Traumatic History of the Industrial Revolution,” in Hydroplutonic Kernow, op. cit., 123–127: 123.

[55.] Negarestani, “Revolution Goes Ferric,” 123.

[56.] Ibid.

[57.] Ibid.; Dwek, “Iron,” 1.

[58.] Cf. Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, trans., R. Brassier (London, UK: Bloomsbury, 2008).

[59.] Mackay and Moynihan, op. cit., 11.

[60.] Stephen Baxter, Ages in Chaos: James Hutton and the Discovery of Deep Time (New York, NY: Tom Doherty Associates, 2003), 210.