This piece was developed while participating in Matteo Pasquinelli‘s seminar, Capital as Computation & Cognition: From Babbage’s Factory to Google’s Algorithmic Governance, hosted by The New Centre for Research & Practice in March 2015… The status of robots and workers under cognitive capitalism can be likened to Searle’s Chinese Room, as noted by Srnicek and Williams when writing on high frequency automated trading. What was initiated by Searle as an argument emphasizing the alienness and stupidity of artificial intelligence, complete with Orientalist framing, is here repurposed to view the subject of the “workerobot” within the calculating machine’d political economy.

Dreams In the Silicon Chamber

In John Searle‘s Chinese Room thought experiment, we imagine a locked space where a person is given messages written in Chinese. Without knowing the language and only through consulting a very comprehensive manual on the topic, they construct written replies to carry on a discussion with someone from the outside. Searle created the scenario to parallel and critique Turing’s test for distinguishing between humans and artificial intelligence. Searle’s scenario emphasises the stupidity of the person in the room, who blindly follows a rule book in order to connect in a basic manner to the machine in the Turing Test and other AI beings.

I have inputs and outputs that are indistinguishable from those of the native Chinese speaker, and I can have any formal program you like, but I still understand nothing. For the same reasons, Schank’s computer understands nothing of any stories, whether in Chinese, English, or whatever.

–John Searle, “Minds, Brains and Programs” (1980).

The argument highlights useful distinctions between representational information processing and semantic understanding. The human in the room is a blind follower of rules without understanding, and hence “stupid.” Deleuze describes stupidity as an inability to dissociate from presuppositions, or, in other words, unexamined doxa or representation. In the Chinese room the presuppositions are bound in the form of a codex, which the human inside slavishly follows. The worker also doesn’t attempt to address the disconnection of the room, or perhaps they are prevented from doing so. Room and rules are “[N]either the ground nor the individual, but rather this relation in which individuation brings the ground to the surface without being able to give it form,” using Deleuze’s description of stupidity (Difference and Representation, page 152; 1994). He goes on to call it “a specifically human form of bestiality,” (ibid, page 150) which also suits Searle’s cage. Srnicek and Williams recall Searle to point out that high frequency trading (HFT) systems, though much faster than humans, are simply very fast information processors, lacking semantic sophistication, or craftiness: they are not cunning automata.

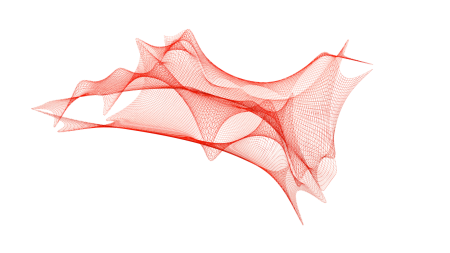

About 200,000 bids and asks from 8000 Stocks at the close of January 4, 2013. (Image from Nanex).

There are various objections to Searle’s argument (see the entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for examples), and here I follow the common “systems” view that the room, rulebook, and person can together be said to think, as cognition is an attribute of the system as a whole, but not the rule-following human within it. The human in the room-system acts like the CPU of a computer, only executing instructions on a very limited pipeline of localized input data, the sentence for translation, but not holding the overall program or system state [see Rey, Georges (1986). What’s really going on in Searle’s ‘chinese room’. Philosophical Studies 50 (September):169-85]. The room-system can still think in the same way the computer-system can still compute, despite the limited scope of its parts. The stupidity of the isolated, confused, rule-following human inside the mechanical room contrasts with Gilbert Simondon’s description of a technical mentality as, “a mode of knowledge sui generis that essentially uses the analogical transfer and the paradigm, and founds itself on the discovery of common modes of functioning or of regime of operation in otherwise different orders of reality that are chosen just as well from the living or the inert as from the human or the nonhuman.” [Simondon, Gilbert, ‘Technical Mentality’, translated by De Boever, Arne, Parrhesia Number 7, 2009].

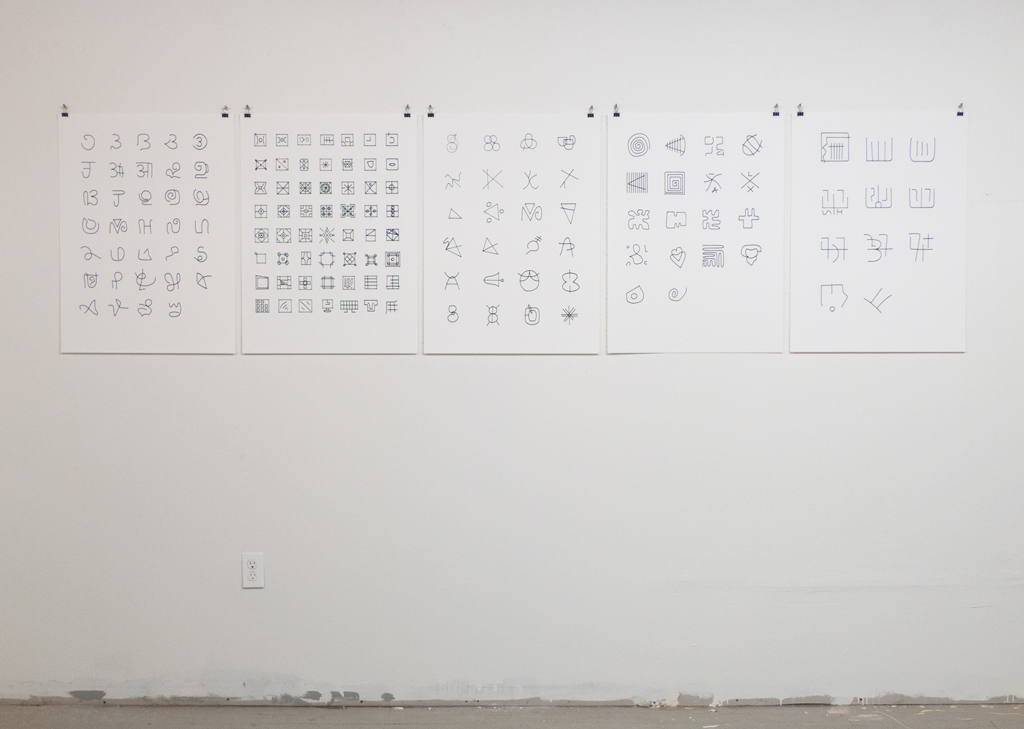

The use of the Chinese language by the English speaking Searle self-deprecatingly emphasizes his own ignorance, and by extension the ignorance of the person in the room: “To me, Chinese writing is just so many meaningless squiggles.” This also rhetorically draws on a cultural framing of the Chinese language as something alien, mysterious or inscrutable. His view is Orientalist in the sense of Edward W. Said, framing one of its parts as inherently disconnected or “other.” The elements of the system associated with Chinese are all mechanical or formal symbolic processors, the Chinese characters input and output, the formally stated rules, and the (implied) system for associating rules with inputs and outputs.

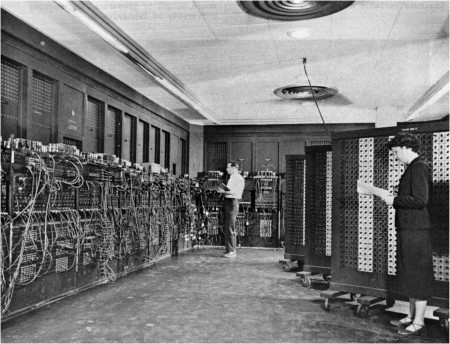

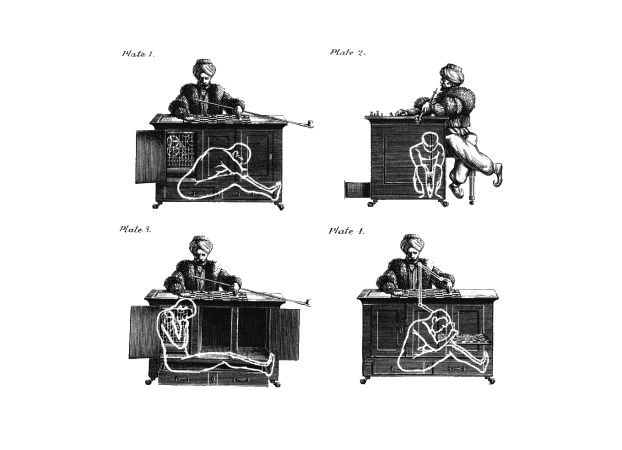

The Turk, also known as the Mechanical Turk or Automaton Chess Player was a fake chess-playing machine created by Wolfgang von Kempelen, 1770.

The person in the Chinese Room is physically like the person inside the historical chess-playing Mechanical Turk created by Wolfgang von Kempelen. For the Mechanical Turk, the visible machine acts as an automaton, but the decisions on chess moves are made by a person inside the device. Compared to the Chinese Room, the role of the human is reversed: the person provides the intelligence, the machine is a puppet. However, the rhetorical use of orientalism is the same in both: the plausibility of the cognitive aspect of the machine to the viewer depended on the otherness of Turkish culture to 18th century west European society. Ayhan Aytes argues, “The appearance of the image of the Turk […] was a reflection of the inseparable relationship between the Oriental subject and the ontological question of what constitutes human subject. Since the introduction of Byzantine and Muslim clocks and automata during the medieval period, and, up until early modernity, the European conception of Oriental automata functioned as a composite alterity by combining the unknown world of automata with the unknown world of the Oriental.”

In another way, the invocation of the Chinese room argument provokes our sympathy: by placing ourselves in the role of the rule-following translation program, or high frequency trading (HFT) system, and imagining how it would feel for a human to blindly follow symbolic rules without any semantic understanding.

The economy itself, as noted by Friedrich A. Hayek, is a calculator of great power, and a “civilized capitalist machine” to Deleuze and Guattari. There are then two visions of the isolated worker within cognitive capitalism: the Mechanical Turk, where sophisticated semantic reasoning by a human is hidden in a claustrophobic cupboard behind a facade of gadgetry, and the Chinese Room, where formal rules of unknown meaning are followed blindly in a sealed office. These are recognizable in the world today: Amazon, with a deliberately wry historical touch, has a service called Mechanical Turk for integrating human input into software systems, mostly for cognitive grunt work computers are currently bad at solving. Automated call centres guide us with rules through corporate systems we do not have the knowledge to understand, the caller a reluctant occupant of a touchtone Chinese Room. Julian Dibbell also has a capitalism / Chinese Room analogy. It applies to the machinic bureaucracy of Soviet central planning as well; these are visions of human semantic dysfunction within a larger computational system. The alien workerobot is shown isolated from social knowledge, be it Marxian general intellect or Hayekian catallaxy.

![Kuribayashi, Takashi, ‘Trees’, 2015, Mixed Media installation, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore. Author photo [left]; Marcovici, Michael, 'Rattrader', Art and Economy Vol 1 (2014), pp5259, http://www.rattraders.com [right] cognitive capitalism](https://tripleampersand.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/tree-rat-e1463592829476.jpg)

Kuribayashi, Takashi, Trees, 2015, Mixed Media installation, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore. Author photo [left]; Marcovici, Michael, Rattrader, Art and Economy Vol 1 (2014), pp5259, source [right].

HFT systems are fast executors of formal rules, but as Srnicek and Williams note, they lack the cunning, the metis of a sailor or a hunter [for use of this concept see Escape Velocities (Alex Williams, e-flux journal), Mohammad Salemy’s interview with Srnicek and Williams, and Benedict Singleton’s (Notes Towards) Speculative Design]. These systems are tools – sometimes traps - crafted by humans. Even in more sophisticated future forms, such systems are limited by the boundaries of computational reason as described by Giuseppe Longo. In an analysis reminiscent of the early Wittgenstein, Longo describes how getting data from analog sources into a computer imposes a digital mesh that limits the fidelity of the representation to the underlying physical phenomena. The pseudorandom functions used by many software libraries is another Longo example, where computers can only imitate the underlying physical process.

We can accept this restriction on the scope of computing, while still imagining less limited systems where computation is a fundamental or even dominant part. For instance, the use of pseudorandom functions with arbitrary seeds in software is usually one of convenience, or low economic cost. The arbitrariness of the seed is often provided by taking the millisecond value from the system clock; a digital observation of an analog phenomena. These are “natural” phenomena in Longo’s terminology. He also emphasises the otherness of the digital, flatly stating “no natural process computes.” Even the 10 bit scalar input is unlikely to repeat itself in many contexts of running programs. This could be extended to replace the pseudorandom function with an observation of a random physical phenomena: like the radioactive decay of a piece of thorium, or particles in a turbulent fluid, by an instrument attached to the computer.

This suggests a reason for Chinese rooms to exist in a computationally dominated economy: to observe phenomena of human cognition. We can imagine some automated analysis of the computational errors made by the person in the room, and perhaps style variations of written Chinese characters–crudely copied without knowledge of the language–providing an analog input impossible to reproduce digitally. For some systems, human cognition may not even be most suitable or cost-efficient. In Michael Marcovici’s work, rattraders, rats were trained to do foreign exchange trades, with the most successful becoming fat on the profits. The rats have, as yet, been unable to convert this schooling into employment in the financial sector, as they got tired after ten minutes of trading; unable to maintain the speed of information processing required (they were dromologically overwhelmed). Price data was given to the rats in the form of generated music. The office cages where the rats worked were designed in a high modernist style: visibly as transparent as Philip Johnson’s glass house or a Skinner box (otherwise known as an Operant Conditioning Chamber), but semantically as opaque as Searle’s room.

The obvious extension is to have computational trading systems observe the rats as an analog input. The elite rats selected by open competition in Marcovici’s project did, after all, get superior return on investment to many human traders. There’s no reason for capital to discriminate based on race, creed, or species. At its limit, if the problem is of a digital mesh, there’s no reason the input would even have to be cognitive; perhaps a computer system could observe the movement of a sunflower turning to face the sun. Perhaps that is enough, but what chooses the sunflower as an input? There still seems to be a cognitive gap in creation of the model, the recognition of a good input, and its conversion into a digital signal (let alone the materiality and craft required in agriculture). Modeling and craft appears to be a more inherently cognitive activity, because it is more than raw correlation: we still need semantics.

The anticipated emergence of cunning automata, as Srnicek and Williams term them, may not require a rewrite from scratch, starting from remaking computational fundamentals on less digital lines (quantum computers, complexity theory, etc). Digital and analog parts form systems that exceed their own limits. This is more or less a cybernetic view, but the cybernetic mechanisms of feedback and digital / biological similarity aren’t the focus of this discussion. Human operators work on digital computers making intuitive judgements based on statistical models. Using algorithmic trading for financial derivatives of agricultural produce growing, from instructions coded in DNA responding to chaotic weather and reaped by remote controlled driverless industrial harvesters; all within an overarching economic calculation machine using prices to transmit and manage knowledge globally. If automata lack cunning, it is perhaps because current interfaces to analog sources of cunning are too indirect. They are too abstract, in the sense of Simondon’s abstract machines [see Simondon, Gilbert, ‘Du mode d’existence des objets techniques’, Paris, Aubier, Editions: Montaigne: 1958. Translation: Mellamphy, N, ‘On The Mode of Existence of Technical Objects‘, University of Western Ontario, 1980.]. Our computing systems’ naïveté may be an artifact of their immaturity – their antisocial relationship with humans and an analog world – rather than a fundamental limit. In the evolution of these technical objects, and their operators’ culture, they can concretise to form cunning systems. It becomes an interesting engineering detail that some of their internals are digital.

My repurposing here of Searle’s thought experiment as economic analysis is something of a caricature, with, perhaps, both the clarifying and distorting effects of that form. The isolation and confinement of the worker and the narrowness of the informational channel are extreme, and this in turn makes the worker’s ignorance plausible; thus, highlighting semantic/information and analog/digital binaries. It’s a sketch of bureaucratic dysfunction. Though lots of work is done by the beleaguered Chinese translator–timesheets will be satisfyingly complete and GDP increased–it’s hard to imagine it helping anyone. It’s less a flow of information than a flow of stupidity (in the sense of Deleuze and Guattari); it is anti-production created while following unquestioned presupposed rules.

However, an element characteristic of our era of cognitive capitalism is the breadth of access to digitised information, as well as the expansion of informational networks mediated by computers in the economy and society at large. One reason for the impact of Searle’s Chinese Room argument may be it predating Google Translate or even more recently, The Pilot from Waverly Labs. An element of Searle’s scenario can still relate to this extravagance of information: in some interpretations of the scenario, the worker can speak English intelligently and freely. The worker operates in two milieus: one of conscious linguistic meaning, the other of tedious rule following. Yet, the worker is schizophrenically unable to relate the two. The flood of information available in English is of no help to the problems phrased in Chinese (the rat can look out the window but it doesn’t help it understand the music). Searle’s Chinese Room describes the absurdity and alienation of work life when technical mentality is absent.

When one puts railroad tracks over hundreds of kilometers, when one rolls off a cable from city to city and sometimes from continent to continent, it is the industrial modality that takes leave from the industrial center in order to extend itself through nature. It is not a question here of the rape of nature or of the victory of the Human Being over the elements, because in fact it is the natural structures themselves that serve as the attachment point for the network that is being developed: the relay points of the Hertzian “cables” for example rejoin with the high sites of ancient sacredness above the valleys and the seas. Here, the technical mentality successfully completes itself and rejoins nature by turning itself into a thought network, into the material and conceptual synthesis of particularity and concentration, individuality and collectivity because the entire force of the network is available in each one of its points, and its mazes are woven together with those of the world, in the concrete and the particular.

–Gilbert Simondon, “Technical Mentality” (1980).

Simondon describes the well made technical object as intermeshing different milieus in a coherent and mutually supporting way. The creators of such objects must have a technical mentality that lets them interpret both milieus, and construct objects that interface between them. In Searle’s Chinese Room, the worker in the abstract machine sits at this interface, but cannot shape it as a designer. This suggests further thought into criterion for worker empowerment. When a human operator has a technical mentality, they can learn from the platform and have the tools to improve it. The worker can then become a designer with the means to extend a technical system and an operator using the system; both individual component and director of the technical ensemble, whom is able to work in the room and open the door.