Contemporary digital technology, particularly the unsupervised strains of contemporary “machine learning”, can be approached with two mental images. The first is de-spatialization, or “black boxing”. The second is re-spatialization, or “spectacle”. The following short essay will be of use to those interested in the work of the ‘critical phase’ of computational media theory and practice inasmuch as it seeks to demonstrate that theorization of nature has utility to the practice of political technology. Philosophically trained readers will not find extended or layered discussion here of nature’s rich history as a philosophical concept, nor theoretically within the contemporary discourses of the post-natural, the non-human, or the even specifically of the computational. The work enacted in this writing is more flatly a pointing towards (not a cataloguing) the material concerns and cultural facets of contemporary rural space as a critical milieu crucial to further theoretical and philosophical anchorings of political computational praxis.

We begin with the two images of thought, black box and spectacle (and it should be asterixed here that I also will not take up spectacle in its own theoretical genealogy), in order to anchor our understanding of the political in political computational praxis within the space of contradiction that constitutes crushing blind spots in computational media today, namely those at the popular failure to grasp the dually (both) discrete and continuous character of ‘computational’ ‘media’ today. That is, by anchoring our notion of political computational praxis in a double-headed mental image-set of the black box and the spectacle, we can start our discussion of political praxis within division rather than within a non-critically assembled notion of continuity. The novel position produced (or meant to be produced) by the following pages will demonstrate that it may only be through the “natural” that a political computational praxis can be assembled. It may only be in the more-than-human relation between the human and the non-human that an actually political technology can develop.

Emerging from the WWII military lexicons of cryptography, code-breaking, and strategic speculation – what historian of science Peter Galison has called the “ontology of the enemy” (Galison, 1994) – the term “black box” refers to the abstraction of a given object or phenomena into an opaque “box” visible only through specifically designated functions or inputs. Underlying this figure is a profound post-war utilitarianism: we don’t care what is in the box, only what its utility within a given context might be. As media theorist Alexander R. Galloway puts it:

The behaviorist subject is a black-boxed subject. The node in a [networked] system is a black-boxed node. The rational actor in a game theory scenario is a black-boxed actor (Galloway 2010, 5)

In the second half of the 20th century, we see this type of logic rise to prominence in a mode of production through which computerized systems function in their first instance (and in my opinion still do today) to de-spatialize objects, bodies, and events into numerical abstractions which in themselves do not carry the same spatial or spatiotemporal nature as that presupposed by prior geographical, geopolitical, or perceptual frames.

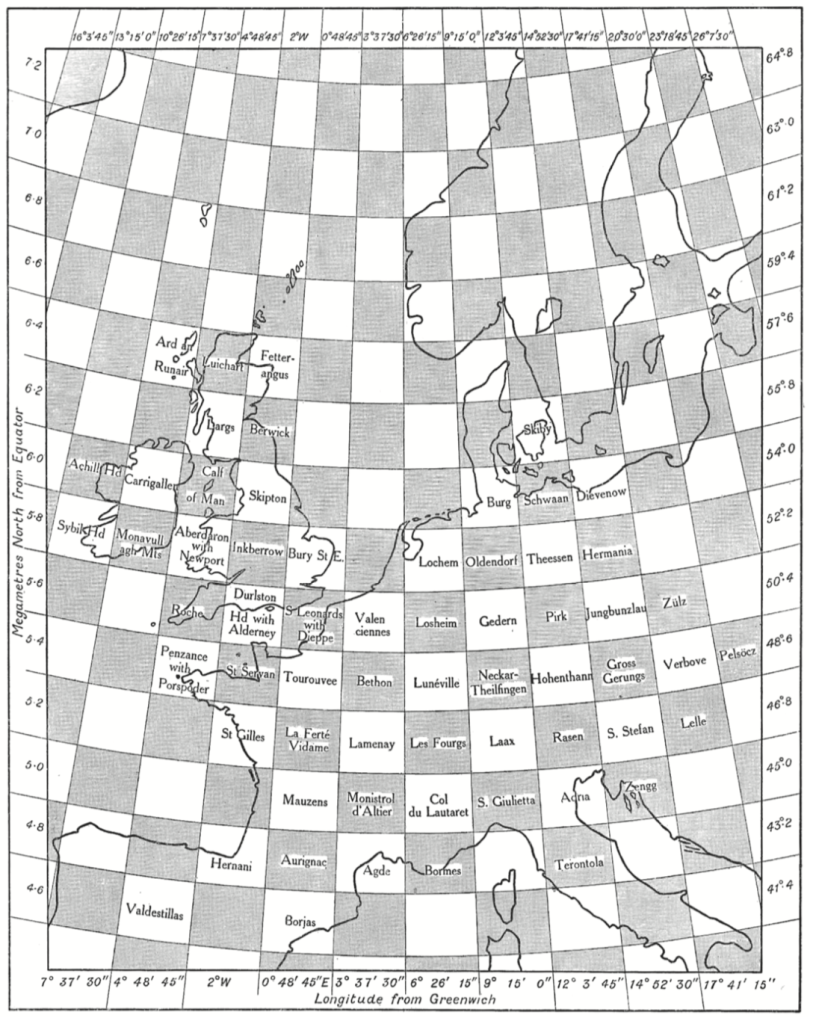

Ruminating on the history of computer science and the post-war field of cybernetics, Galloway describes this de-spatializing infrastructure as a “crystalline space”. Quoting from English mathematician Lewis Richardson’s early research in 1922 on a “system to predict weather via a cellular space of distributed meteorological sensors”, Galloway observes that:

Simply overlaying a grid on a map is not the attraction of Richardson’s system for the present investigation. For in Richardson’s case the grid is not primarily a spatial technology. In fact, while the grid exists in an entirely abstract geometric space oblivious to national borders or geographic features, as does the system of latitude and longitude, it is, more importantly, a latticework of parallel calculation. Each square is represented by a number that feeds into an overall algorithm for modeling atmospheric phenomena. As the cyberneticists would later discover, the establishment of this kind of lattice or crystalline space requires the encapsulation and obfuscation of each individual crystalline cell, a technique that scientists call “black boxing” (Galloway 2014, 117-8).

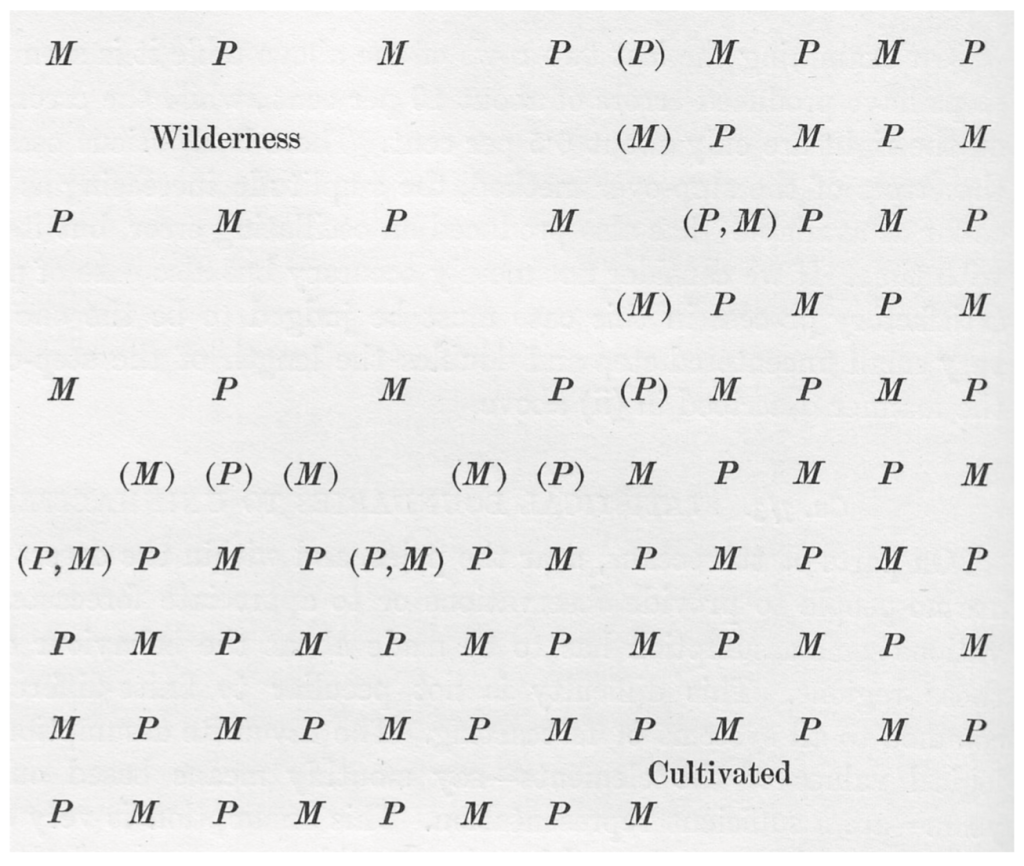

This is the basic utilitarian essence of the black box: the ability to take an object like part of the surface of the globe and abstract it numerically into a lattice of mathematical functions. In doing so, Richardson’s crystalline grid furnishes an arithmetic capacity to measure and even predict changes in atmospheric pressure as it registers for this massive-scale calculator. However, working within the constraints of a real geological region, Richardson’s system had also to confront problems of density in the plotting of its mesh of sensors. Since rural and uncharted areas, says Galloway, “would likely have fewer meteorological sensors, the grid in that zone would have to be spaced wider apart, whereas a heavily populated part of the land mass would have a surplus of sensors and therefore a tightly interwoven framework . . . So, reflecting the so-called asymmetry principle of networks—the principle that networks are always internally asymmetrical—Richardson developed a technique for dealing with unequal density resolutions that by necessity must be ‘interfaced’ or integrated into the same overall map. He called these thresholds “joints.” Such joints must be established between the low resolution zones of the wilderness or the open ocean and the high resolution zones of the cultivated areas and the land masses (as opposed to the sea)”. As Galloway indicates through the operational figure of the interface or of integration, Richardson’s early composition of this terrestrial crystalline ‘space’ held the function of both an de-spatialization as well as a respatialization. In Richardson’s own words:

On parts of the oceans, near the poles, and within the desert tracts of land there are no people to provide observations or to appreciate forecasts. [. . .] [T]here are other portions of the globe, especially the seas, where some rough sort of forecast might be possible and desirable if it could be carried out with a much opener network than that in use where the population is dense. But the two networks must be united on the computing forms in such a way that air, represented by numbers, can flow across the joint. (Galloway 2014, 119-20).

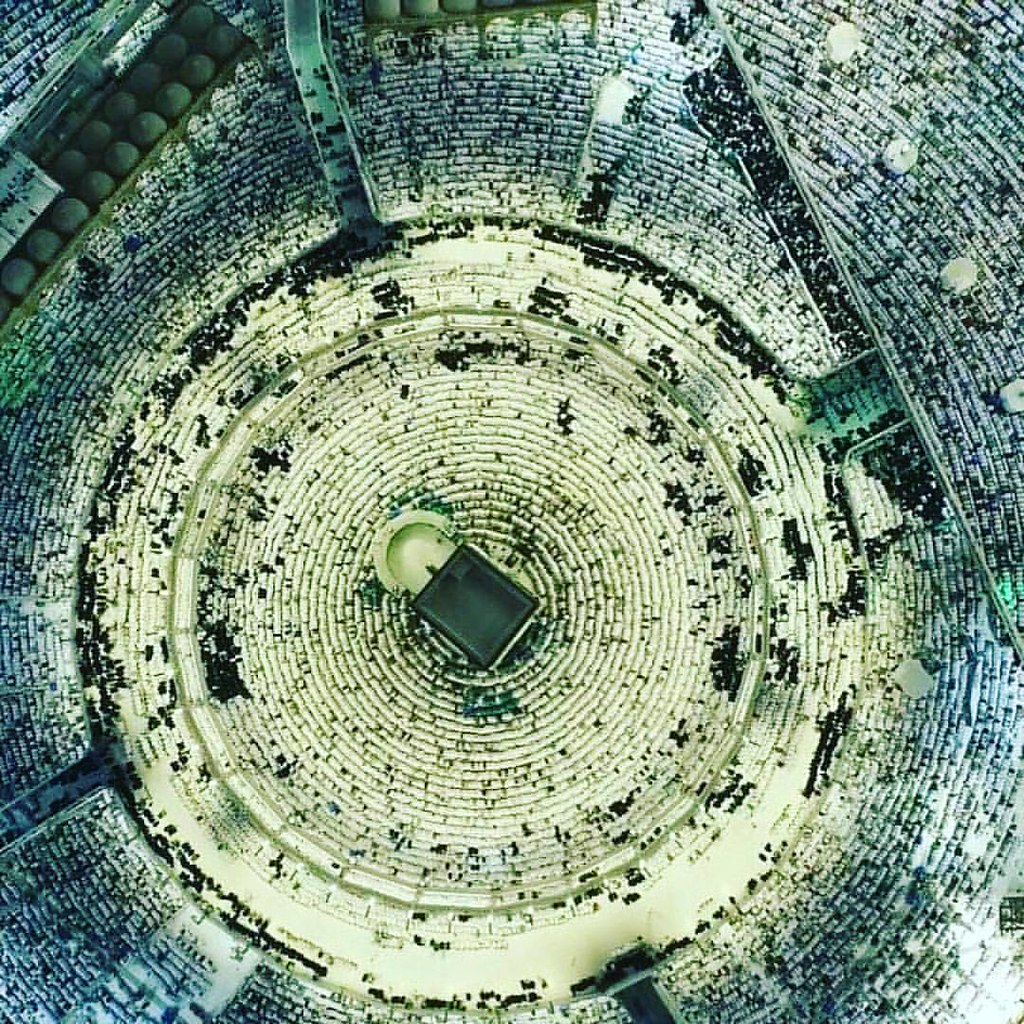

At work here are two modes of thinking, intertwined. In the de-spatializing abstraction of the globe into numerically represented grids, we can see what Galloway in later work calls the Digital (the discrete, or arithmetic) and its mental imaging via the black box figure. And in the re-spatializing “computing form” of air as it interfaces with its “joints”, what he will call the Analog (the continuous, or the differential) and its mental imaging via the spectacle figure. Nearly a century after this weather system’s composition, we see the same material furnishing of the digital with the analog in the machine learning algorithms that interface social behaviors, the toroidal flows of hurricanes, the high-frequency spikes of computational finance, and the logistics of migrant populations with de-spatializing lattices and re-spatializing forms of a properly computational spectacle, of a properly digital analog.

In this world, as Achille Mbembe puts it in his 2019 lecture on “Borders in the Age of Networks”, geopolitics become a matter not so much of the fantastic ever-stretching border wall but increasingly of computerized systems of borderization in which black-boxed subjects are abstracted and measured in everyday life everywhere in the world in order to not only regulate speeds and movements across and between nation states but also to transplant this regulation of speed and movement from the an industrial geopolitics to a computational geopolitics. Suckling from the networked feed of subjects-abstracted-to-numbers, the news media, entertainment, corporeal force (and many other categories of interference) aim at “slowing down the dynamics of people [to people] interactions, at creating distance or shattering the chains of relation between them, so as to institute new patterns of separation” (Mbembe, 2019). Borders, in short, in the age of networks, exist in the digital production of the existential patterns in our psychosocial conceptualizations of interpersonal difference. Borders are translucent and transtemporal walls snaking between groups. Because we are all abstracted, de-spatialized, black-boxed, the grid can re-spatialize us however it needs to and however it wants to. In this mode of life, the border is less the wall or the fence (although, of course it is this too…), but more so the airport, the duty-free, the Chanel store, the multi-medial real-time delineation of consumer-population types that flower to prevent solidarity, sociality, and interpersonal or emotional security.

This is abuse as spectacle. The question is, how is this life spectacle rendered so as to seem normal, natural, and in the case of climate change, even destined. Why is it that we feel the violence of Donald Trump’s televisually prostheticized psychopathology in our bodies? Why is it that our land feels the perversity of the global petroleum czars in its furrow and farrow? Indeed there are deeper questions at work here regarding the relation of materiality and the traumatic that we can only begin to think through with these tools. One of the pre-eminent scholars of black studies in our times, Sylvia Wynter, observes in 2015 that what many call today even colloquially the “mode of production” (or even simply the quotidian conceptions of development, construction, engineering) is wrapped in and suffuse with the existential and cultural patterns of white power, a historically unique mode of power that seeks endlessly to pose the white billionaire man as the pure biological model of what it means to be a human. To contest climate change, says Wynter, we must confront the cultural myths of white power in their spectacular intertwining with their/our planetary scale infrastructure. Anything else, any failure to fully confront the imbrication of the world’s production with a white power, results in catastrophe. The path to victory, given this diagnosis, is for Wynter nothing other than to challenge the biological “overdetermination” of white power qua humanness through the signal-wire of mythos, given that in Wynter’s framework the bios and the mythos are themselves ‘dialectically’ related (Wynter 2015).

The cultural myth, defined here by cultural theorist Stuart Hall, is a narrative pattern or story that plays across our everyday life. To quote Hall:

Every time I watch a popular television narrative like, well say, ‘Hill Street Blues’ or ‘Miami Vice,’ with its twinning and coupling of racial masculinities at the center of its story, I have to pinch myself and remind myself that these narratives are not a somewhat distorted reflection of the real state of race relations in American cities . . . They are functioning much more as Levi-Strauss tells us myths do. They are myths, which represent in narrative form the resolution of things, which can’t be resolved in real life. What they tell us about is about the ‘dream life’ of a culture. But to gain a privileged access to the dream life of a culture, you had better know how to unlock the complex ways in which narrative plays across real life. Once you look at any of these popular narratives, which constantly in the imagination of a society construct the place, the identities, the experience, the histories of the different peoples who live within it, one is instantly aware of the complexity of the nature of racism itself (Hall 2006).

The task in our opinion for computational media scholarship today is to conceptualize this mythic axis of everyday life in the era of digital infrastructure, of coming up with a way of hearing the mythic in an age of black boxes and spectacles. In contrast to the position taken up by design theorist Benjamin Bratton that technology supersedes representation (Bratton 2019), we reintroduce the myth here as a specific deployment of a culture-valorizing framework in order to re-engage with the notion of the natural as it relates to development, engineering, and the mode of production. By recognizing the arbitrariness of the mythic component of cultural production (of the “[representation in narrative form of the resolution of things which can’t be resolved in real life]” which play across our old and new media forms, from the tele to the border), we can conciliate with the uncontrollable dimension of life in which the political irreducibly finds its form. In this conciliation, we can also find new modes of knowing not reliant on an agential modeled in white power and we can develop, possibly, novel forms of reason.

Following a recent essay by Galloway on mathematics (or, Mathification), we offer that this revisiting with the natural may require a strategic essentialism, or a “strategic essentializing”. As he puts it:

Criticality is so thoroughly disempowered today, the velocity of co-optation so rapid, the inversions of political desire so complete, perhaps the only truly revolutionary act available today is to promulgate a kind of strategic essentialism—as if to say that no sort of direct, rational process will ever yield results, but that they will arise instead from those irrational processes, those untranscendable horizons, that abyss and that impasse that fix the very coordinates of nature itself (Galloway 2019, 107).

It may require an examination of nature not only as a geographic or geological or sociopolitical concern but also as all of these together in the form of an existential examination of the mythic and politics. Now that nature, and the category of the natural, has inverted from its own modernist ideograph of fertility, romance, and adventure – and resounds instead today towards the anthropocenic horror of death, extinction, extraction, and despair – we think that we have to have the courage to let in the unbounded violence of this world, of the unfixed nature upon which nature itself floats. In opposition to the urbanistic lure of development, planning, and production that has been centered in the metropolitan-architectural response to climate change (characterized by carbon capture farms, terraforming, and mentalities of a hydraulic cosmos [don’t we already live in that world?]), we offer here the thought of the rural. Not the bucolic rurality of the Victorian age, but the new rural: twinned as it is in the two figures of the disfigured landscape and the ghost of another world, either or both extinct and extant. Already haunted in the invisible shadows and bodyless under flaps of digital ‘space’, we conjure the story of ghosts as a way of refurbishing the ecology of myths in the landscape of this nature that we must live with.

When working creatively and/or critically with the computational, it is imperative that we avoid two types of problems. In the first case, we have to avoid brute statistical reductions (or black boxing) of complex and morally sensitive data representations – as is the case with the use of algorithms in the well-known juridical and carceral contexts. In the second case, however, we have to avoid the generation of spectacle, of the exercising of a computational autonomy over the existential patterning of life. In his remarkable and terrifying 2019 video essay, “Control, Climate, Capitalism” artist-scholar Ian Alan Paul expresses the geopolitical importance of this second caveat. With special emphasis on computational media practice and production, he theorizes that the only phenomenon which will move faster than computational-scale ecological traumatization is its aestheticization by an temporarily autonomous bourgeois. Through an “aestheticization of the sublimity of extinction” (Paul 2019), he says, wall street traders and policy officials will engage in the romance of planetary decline through the operations of a new, and yet not, tourism.

Similar to the way in which scientific socialism has diagnosed the increased antagonism between town and countryside as a core feature of capitalism, it is possible that new theoretical formulations of nature, with a valorizing centering of the rural, can inform our interrogations of the existential functions of capital in the Anthropocene without abstracting the notion of the commons away (spatially or temporally) from daily life and its praxis. By taking into account a theoretical conceptualization of and material practice in rurality in the Anthropocene, political computational media practice and its machinic/artificial operations can be opened onto the horizontal stage of myth and myth-making. This opening is in our opinion at least one part of the more diffuse opening of the mode of production to a cultural complexity which would constitute what Wynter has preemptively called the Third Event (Wynter 2015, 217): of a truly ecumenical human emancipation achieved through an enacted and developed recognition of a dialectical supersession of the mythic over the biotic. By taking up the rural as a material milieu less obscurantly veiled from the mythic productions of nature than the urban and it’s bicyclist theoreticians, we might stumble on new power. In antithetical response to Bratton’s 2019 leitmotif, “Where do the cities go?” (Bratton 2019), we ask “Where does the power go?”

Bibliography of Works Consulted

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Terraforming. Moscow, Russia: Strelka Press, 2019.

Galloway, Alexander R. “‘Black Box, Black Bloc.’” The New School. Lecture, April 12, 2010.

Galloway, Alexander R. “Mathification.” Diacritics 47, no. 1 (2019): 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1353/dia.2019.0013.

Galloway, Alexander R. “The Cybernetic Hypothesis.” differences 25, no. 1 (2014): 107–31. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-2420021.

Galison, Peter. “The Ontology of the Enemy: Norbert Wiener and the Cybernetic Vision.” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 1 (1994): 228–66. https://doi.org/10.1086/448747.

Hall, Stuart. “Stuart Hall – The Origins Of Cultural Studies.” Vimeo, June 11, 2020. https://vimeo.com/47772417.

Mbembe, Achille. “Borders in the Age of Networks | Achille Mbembe – YouTube.” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFGjzG0lLW8.

Paul, Ian Alan. “Climate, Capitalism, Control.” Ian Alan Paul, October 14, 2019. https://www.ianalanpaul.com/climate-capitalism-control/.

Wynter, Sylvia. “The Ceremony Found: Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn, Its Autonomy of Human Agency and Extraterritoriality of (Self-)Cognition1.” Black Knowledges/Black Struggles, 2015, 184–252. https://doi.org/10.5949/liverpool/9781781381724.003.0008.