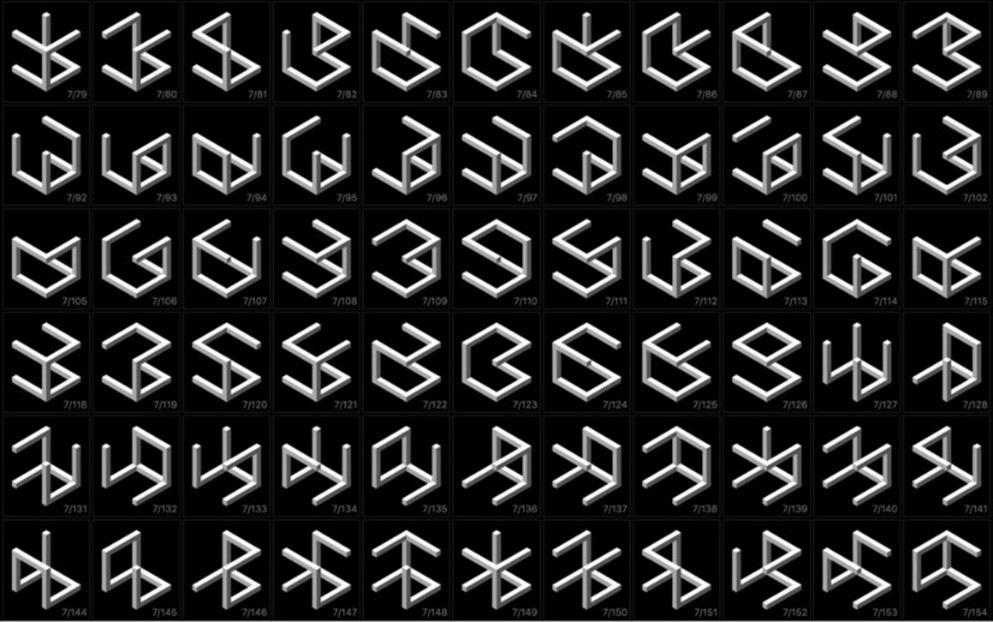

In his course Deleuzian Aesthetics Fares Chalabi presents an extended typology of mutually exclusive, rigorously defined image-types, or what I like to call aesthetic structures or aesthetic logics. An image-type or aesthetic logic is a form that structures the entirety of a work of art – take, for example, the ‘series’. The logic of series, Chalabi explains, can be seen in works such as Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes or Jean-Luc Godard’s Les Carabiniers. Such works of art are made up of different variations on a single notion, in an attempt to question or problematize something about this notion. In the case of Godard’s film, it is the notion of war that is being serially questioned; for LeWitt, it is the notion of the cube.

Some of Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes

Deleuze conceptualized several image-types in his two Cinema volumes, namely and respectively the movement-image and the time-image. What Chalabi attempts is to adopt and extend Deleuze’s typological system so as to make sense not only of all film and cinematic art, but more generally, all images. His course covers the aesthetic structure of phenomena like medical imagery, advertisements, and even GoPro videos of people doing extreme sports. This essay follows Chalabi’s bastardization and generalization of Deleuze’s film aesthetics: after all, at the end of Cinema 2, Deleuze invites others to add to his ‘period table’ of image-types.

Chalabi makes one contribution to the ‘periodic table’ with his sectarian image, which articulates a particular aesthetic logic functioning in the works of Lebanese filmmaker Maroun Baghdadi. The sectarian image is defined by characters and spaces making abrupt shifts in their nature, sudden transformations into something or someone else: friendly civilians turn into kidnappers, hospitals function simultaneously as tobacco stands, tourist and residential areas suddenly become war zones, etc.

I’d like to attempt a contribution to this typology of images: the narcissist-image, characterized by an oppressive montage that forces one context, motif, element, etc. onto a pre-existing artwork, context, or motif.

In his course, Fares Chalabi lays out a problem that the art world is ‘pregnant’ with, this being the problem where something that is not art is imposed upon actual works of art. How often have we all been to an artist’s talk or lecture about art and suddenly the topic becomes psychoanalysis or Marxism or something of the sort? To put it in Chalabi’s words: nobody seems to look at the ‘image itself’ when dealing with art.

This very act of imposition, I wager, is the logic of the narcissist-image.

Still from The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema

Consider Chalabi’s critique of Žižek’s reading of Hitchcock’s The Birds or Psycho: that Žižek reads these films through psychoanalysis and does not read the films themselves. Žižek of course himself has avowed taking part in this general logic of reading art. In his discussion of The Joker, he even admitted how he not only did not view the film but avoided viewing it out of fear that his prior reading would be disproven. This is not to say that Žižek’s readings have nothing to offer, but that they are not readings of the films themselves; rather, they are readings of the world, as explained and schematized through film. The above photo of Žižek is a narcissist-image par excellence: Žižek super-imposes himself onto The Birds’ pre-existing diegetic space.

By contrast, Chalabi’s demand for formal rigor when producing readings of art has the opposite effect on works of art themselves. It frees art, for better or for worse, from the need to function in a diagrammatic, explanatory way, from functioning as a tool serving something which is outside of art, such as politics or the social sphere. Do not misunderstand: art can still be political or social, but it cannot, or should not, be a mere explanation of political or social phenomena. This essay is not only an attempt to contribute to Deleuze’s periodic table of image-types or aesthetic logics. It is moreover an attempt to present a logic that is itself evocative of the privilege that art enjoys, and which readings of art do not.

The Narcissist-Image

One of the many ways Sam Vaknin schematizes narcissism is as a montage: the narcissist montages herself onto the lives of others, places herself seamlessly at the forefront of different situations, instead of engaging with them as they are. Rather, she engages with them as she is. Beyond being a pathological affliction, this is also a peculiar aesthetic logic. What defines an image that functions narcissistically is not a form of personal self-importance or social self-obsession – it is the very impersonal logical structure of narcissism, that of making everything about ‘you’.

Stills from Nosferatu

Montage, in the conventional sense, usually functions by putting two images together whose sequencing shows you a relation between the two. For example, these consecutive shots from Nosferatu function in this exact way. In shot one, on the top, we see a man entering a room through a door and looking inside. The shot immediately after, on the bottom, shows a woman, in a room, who stops knitting and looks in another direction. From the proximity of the two shots, the audience infers that these two people are looking at each other.

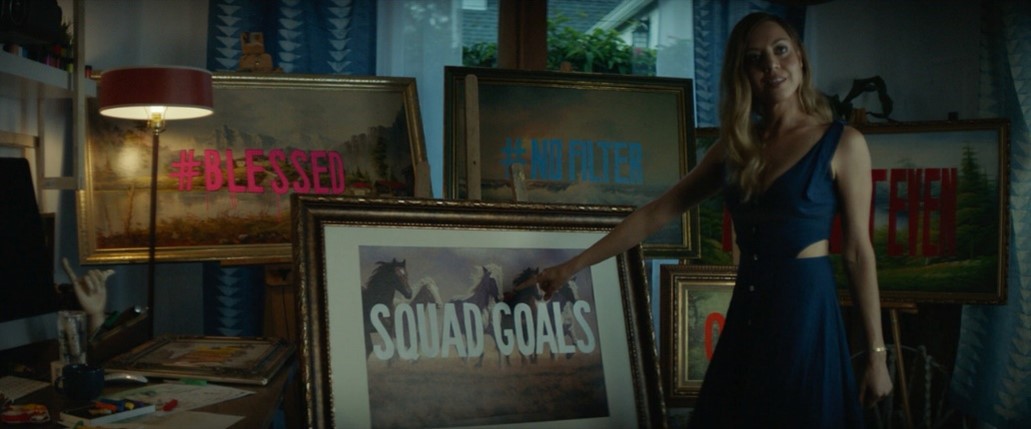

The narcissist-image functionalizes montage differently, by giving primacy to one of the elements being montaged, namely the latter one, the one which is super-imposed onto the other. One great example of the use of the narcissist-image is the work of the fictional artist Ezra O’Keeffe from the film Ingrid Goes West.

Still from Ingrid Goes West

In the above still from the film, we see Ingrid Thurburn, the film’s main character, standing next to Ezra O’Keeffe’s work. This fictional artist’s practice seems to center around bringing pre-existing, furniture quality, academic paintings of rural and natural scenery, and superimposing text onto them. The texts superimposed are familiar social media phrases: “squad goals”, “#blessed”, “#nofilter”, “not even”, and so forth.

Screenshot of Seinpeaks video

Sound can be an equally imposing presence in aesthetic narcissism. In the above video, “Audrey’s Dance” from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks is played on top of a scene from Seinfeld, taking it over, filtering its affected sensibilities. Seinpeaks, a world that exists in videos and images on different social media platforms, is not a mixture of the worlds of Twin Peaks and Seinfeld. Rather, it is a collection of different memes that superimpose Seinfeld onto Twin Peaks (and other Lynch films) or vice versa.

Noah Verrier’s El Pollo Loco

Consider the work of Noah Verrier, who paints still lives of fast food in the style of impressionist painting. Here, the superimposition happens within the painting, not on top of it. The superimposition happens at the thematic level: 21st Century subject matter are superimposed onto a 19th century style of painting.

Screenshot of Google search of Disney Princesses Reimagined as

Another example of aesthetic narcissism is the ubiquitous illustrated article format known as “Disney Princesses Reimagined as…”. This format takes one or more Disney princesses and parachutes different motifs and themes onto them, be they parenthood, homosexuality, contemporaneity, or otherwise. In this example, both what is superimposed and what has been imposed upon happens at the thematic level, at the level of content. In other words, the artists making these illustrated articles do not use a style or animation similar to that of Disney movies, for example making footage of war-torn Iraq drawn in Disney style. In the “Disney Princesses Reimagined as…” format, the imposition of content, such as parenthood, is placed on top of already existing content: Disney princesses.

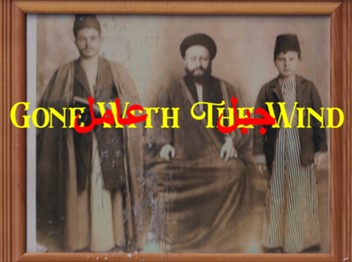

Poster for Gone with the Wind Jabal Amel

I myself have produced artistic work with a narcissistic aesthetic logic of oppressive montage. In 2022, I produced a curation of documents pertaining to a remake of Gone with the Wind set in the Lebanese south, Gone with the Wind Jabal Amel.

This work, however, as is evident from the poster, included many simultaneous sedimentary layers of imposition: Gone with the Wind imposed onto Lebanon, Lebanon imposed onto Gone with the Wind, etc. If one gets into the details of the project one can even find other impositions such as imposing the Lebanese civil war onto the 19th century American south, then imposing that very imposition onto the contemporary Lebanese context of Shia domination, and further even imposing the notion of a director’s commentary onto the notion of an artists’ talk, among others.

The Privileges that Aesthetics Enjoys

Still from The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema

When revisiting Žižek’s reading of Psycho – which articulates the three levels of the Bates’ home as the Id, the Ego, and the Superego – one might want to ask questions like the following: Is there no truth to this schematic psychoanalytic articulation? Does Norma Bates’ incessant nagging not mirror the critical agency which is the Superego? Does the ground floor not represent a maintained level of appearances and normalcy like the Ego? Does the basement scene unveiling Norma Bates’ actually dead body not truly mirror the Id’s concrete, almost physiological character? The answer to these questions is: of course it does, of course they do.

This is not the problem. The problem is that this is not the structure of the film Psycho, but the structure of part of its content which merely mirrors in one respect the contents of something found in psychoanalytic theory. The real problem is that Žižek specifically uses the film to explain something about psychoanalysis.

Still from Romeo & Juliet

The difference between Žižek’s reading and Ezra O’Keeffe’s work, which could make an equally shaky but coherent comparison between academic painting and social media, is that O’Keeffe’s work is (fictional) art. It does not need and shouldn’t have to answer to the same kind of scrutiny that Žižek exercises. The vulgarity and projection involved in narcissistic-image-making are part of its poetry, effect, and temperament. Part of what is so engaging and enticing about narcissistic-images is this oppressive and imposing manner. A great example of the poetry involved in this vulgarity is the film Romeo & Juliet. Central to Baz Luhrmann’s masterpiece is the stark contrast between the modern scenery and pop cultural motifs with the Shakespearian verse being spoken.

Deleuzian Aesthetics confronts its students with a difficult question: If all we look for in art is a mere reflection on the political/social world, or of our own theories, why look at art at all? Wouldn’t it be better to read works of social science or philosophy? Surely those texts will be much more rigorous and serious in their analytic undertaking of the socio-political world. There is a tendency in the art world to project theory and other forms of discourse onto a work of art rather than look at the artwork’s own structure.

Chalabi’s course, in its demand for an almost positivistic rigor on the part of how readings of works of art should be conducted, also frees art from a kind of scrutiny, namely the scrutiny of theory. With Chalabi’s course (and perhaps even Deleuze’s aesthetics prior to Chalabi’s expansion), art no longer has to stand for a kind of political position or historical truth, it no longer has to address the audience in an informative manner.

Politics on Aesthetics’ Terms

Though Deleuzian Aesthetics rails against political interpretations of art and art as an explanation of political or social phenomena, this shouldn’t mean that this aesthetic theory can’t say anything about politics. It merely says that when it comes to art, politics must be understood in terms of art: aesthetically.

Kent Monkman’s Resurgence of the People

Emanuel Leutz’s Washington Crossing the Delaware

Resurgence of the People is a recreation of Washington Crossing the Delaware, an iconic and canonical work of North American painting. Monkman, however, (substitutively) imposes his own subjects in the place of the originals; he replaces Washington with his alter ego, Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle, replaces the other men on the ship with indigenous people and immigrants, and even replaces the background of the original painting with another background more appropriate for Monkman’s subject matter.

Jon McNaughton’s Crossing the Swamp

Consider now Crossing the Swamp, a painting by American conservative artist Jon McNaughton which in its presidential content perhaps bears more direct reference to the original painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. The painting shows former president Donald Trump, vice President Mike Pence, and some of their Republican interlocutors crossing a swamp next to the congress building. The motif of the swamp is a reference to Trump’s slogan “Drain the Swamp”.

The politics that one would interpret from Crossing the Swamp are of course not at all aligned with those of Monkman. Both works, however, have an identical logic: both these paintings function narcissistically, by imposing a particular content onto another preexisting work. Both Monkman’s and McNaughton’s paintings seem to understand the America they are intervening on, whether by drawing a continuity with its former greatness (McNaughton) or vandalizing its celebrated history (Monkman), as a pure singular originary identity to be either opposed or embraced. Ironically, neither of these paintings seem to capture the inherent tension of America. They do not capture the tension between George Washington’s personal belief in monarchism and his (perhaps circumstantial) role in building a democracy, nor America’s status as a colonial entity that captured and enslaved a great many people, but is nonetheless a haven of freedom for many, for better or for worse.

Instead, what it should mean to understand politics aesthetically is to look at a work of art’s political imagination, its conception of political dynamics and subjects, rather than looking for a work of art’s political position or propositions. Perhaps then, instead of blindly reproducing the narcissist-image in readings of art, we can learn to read images on their own terms, including artworks which take part in a narcissistic logic.