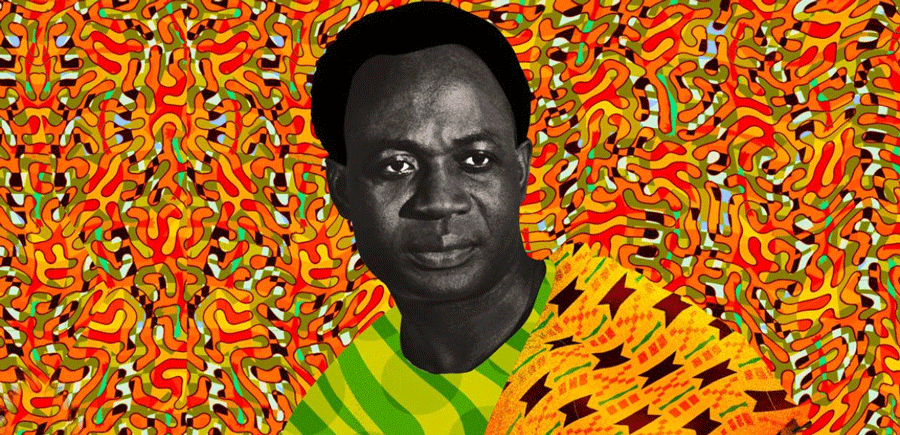

Paulin Hountondji, the Beninese author who died in February and taught philosophy at the National University of Benin, was clearly aware of the magnitude and impact of politician Kwame Nkrumah, since, as he recalls in his autobiography The Struggle for Meaning, his presentation in Paris on the Ghanaian leader’s 1964 book Consciencism caused headlines for suggesting that his thought was more progressive than Négritude. I tell the story here to show how central Nkrumah was in Hountondji’s understanding of both thought and politics. Though for the majority of his career, the Beninese philosopher would be accused of being dismissive of Nkrumah.

One of the late philosopher’s questions is: (1) what is the nature of thought in the aftermath of anti-colonial battles? Then, he asks: (2) what kind of thought can enable the formation of an identity in the midst of such political crises? Houtondji’s questions point to the conceptualization of political theory in the midst of political crisis, and how to write philosophy in a way that adequately responds to ongoing political battles. He offers a problem for thought since he is invested in what it means to think in the midst of such vastly turbulent, changing conditions; and further what is the appropriate approach to study, think about, and even to participate within such political, and, one might argue, ecological events? For some context, Hountondji’s polemic comes after Ghana’s independence in 1957, and after the official formation of the Organization of African Unity and the founding of Africa Day on May 25, 1963.

There are three layers within these two questions and which I want to explain: (1) One of the layers is the context of the anti-colonial battles and Ghanaian independence as the hallmark of the decolonization movement. That means that Hountondji’s question is posed in some way towards an African or Africanist political rhetorical tradition, including and not limited to Kwame Nkrumah and Leopold Sedar Senghor. One of the possible reasons why Hountondji’s 1964 Paris presentation caused headlines is that Négritude was the primary discourse of anti-colonialism at the time, having shaped thinkers such as Frantz Fanon. Both of Hountondji’s questions on the nature of thought demand answers from rhetoric, specifically political rhetoric. And so, inadvertently, they evoke what Gayatri Spivak described as the “ideological victim.” Hountondji’s posture is one that clashes against, while becoming overshadowed by, the field of Africanist political rhetoric. A clarification here is necessary to note that Hountondji’s preface to African Philosophy: Myth or Reality? (1977) includes a discussion of feedback and criticism of his book which cite his remarks on Kwame Nkrumah and his political rhetoric. One might also point out that Hountondji participate within this sphere of political rhetoric while demanding and arguing in writing for a rigorous theory that recalled the philosophy departments in Paris like the École Normale Superieure from which he came.

(2) A second layer of these quite complex questions concerns the notion of identity formation, as well as the long trajectory of anti-colonial battles. I say complex because these concerns are by no means limited to one author, or a set of texts, and rather concern a long period of several centuries. If the emphasis is often on Ghana as the watershed moment for independence, how does one account for anti-colonial and anti-slavery revolts across the continent and in the African diaspora over the same time period? This is perhaps what some have defined as a black radical tradition. The question of identity formation, such as what is the role of identity and personhood in the aftermath of anti-colonial battles, is one that can easily be misconstrued due to its subject (See: Dismas A. Masolo, African Philosophy in Search of Identity). Anti-colonial battles had taken place for centuries prior to Ghana’s independence in 1957. Further, one can ask: what is the nature of the political rhetoric of anti-colonialism? Even this question, according to Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, is one that cannot be contained merely by the speeches of Nkrumah, Kenyatta, Lumumba, Biko and others, but concerns Marxism in an international context. Anti-colonial battles and their Marxist reverberations and rhetorical formations can challenge and reorganize thought.

(3) The third layer concerns a related but ultimately different question posed by Hountondji, when he asks whether the Belgian priest Placide Tempels’s book La Philosophie Bantoue is the founding text of African philosophy. His answer is no. But the inquiry is of interest to me because it provides the place from which the course on Self-writing, autotheory and autoethnography takes off. By directing the question of the founding text of African philosophy (and inadvertently the question of African philosophy) to ethnography and anthropology, Hountondji directs us to structuralism, by providing a structuralist reading about the nature of African thought. This is of interest to me because of his objections to essentialism – the kind of essentialism that he objected to in Placide Tempels. Viewed differently, this inquiry combines the urgency of his epistemic concerns on the political rhetoric of anti-colonialism, with the disciplining of structuralism and its architects. It is here that Hountondji’s questions begin to appear destructive.

In attempting to redirect and hence apply Hountondji’s thinking to the problem or the task of autobiography, how does this destructive nature of his thought intersect with his desire for an explicit identity formation in the aftermath of anti-colonialism? This position encourages my assumption that Hountondji’s ideas are valuable in conceptualizing the self in modalities of writing as well as ethnography (despite his vehement rejection of Placide Tempels’s La Philosophie Bantoue).