1. An Ecology of Possible Worlds

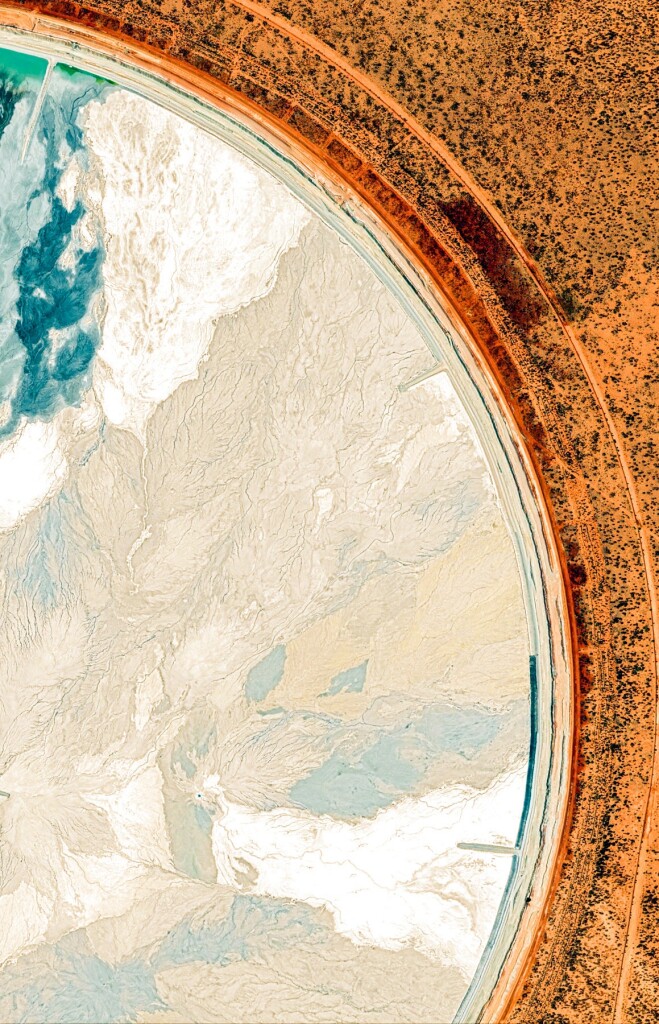

I am often amazed to have access to satellite images with thundering evidence of our species’ capabilities to transform the environment. It is an Earthrise-like aesthetic experience that naturally calls for a philosophical inquiry about the ontology of the human self as part of the Earth’s systems. This essay is devoted to such philosophical inquiry. To begin, I want to talk about a cybernetic framing of worldmaking that we will carry around as we proceed to visit topics such as the planetary and geoengineering into a construction of utopia.

Nelson Goodman’s pragmatist conception of worldmaking does, in my opinion, an excellent job unifying science, philosophy, arts, and politics under the human activity of constructing possible worlds. This construction of possible worlds calls for a relocation of truth from correspondence to reality to certain adequacy of the conceptual representations that regulate individual and collective behavior. Quoting (Goodman 1978, 19) “we might better speak of theories as right or wrong: for the truth of the laws of a theory is but one special feature and is often […] overridden in importance by the cogency and compactness and comprehensiveness, the informativeness and organizing power of the whole system.” If we consider the intentional causes that lead to human constructing possible worlds in the first place, this renders truth as a contending evaluation criterion for the act of theorizing —instead of the only one— and translates scientific, philosophical, and artistic practices to the intersubjective entanglement of situated and embodied cognitive processes. Instead, “we understand ‘knowledge’ not as ‘justified true belief’ but rather as a reliable-enough map of an affording domain“ (Sachs 2018).

One remark I want to adopt from (Sellars 1960) is the distinction that picturing in the human mind —or holding para-conceptual cognitive maps as a representation system of the world— is shaped both with respect to feedback from the environment and feedback from the bodily systems it is coupled with, and it is key to understand that signifying (distinct to picturing) in para-linguistic terms makes part of both the internal feedback and the external feedback in social interaction. Following this I want to acknowledge two forces of change that are central to how we approach the next sections:

1) the theorizing enterprise actually transforms the material conditions of the environment (mediated by control* in the human self)

2) the theorizing enterprise heavily relies on transforming itself (like a second order theorizing of a sort).

The main consequence that is important to note is that, if a revolution is to happen —which I will argue is the necessary way to proceed— then, the ways we frame the interaction between these two must provide the means and ends.

2. Planetary Accidents

Gayatari Spivak’s imperative to re-imagine the planet (Spivak 2012) falls along the lines of the setting I propose. The effects of colonialist globalization render ‘the global’ as this inherently capitalist metaphor that represents the planet as a hollow Earth model with a fixed —and all encompassing— tessellation of its surface into a political realm that gives place to rather problematic ontologies such as national membership, land ownership and strict individuation. In this sense, Spivak proceeds to characterize how the current state of affairs aligns with how subject’s hold (and come to hold) a notion of being global agents. With respect to this metaphor, the environment and the global agent (ontological render of the human self) remain completely separable entities. This notion regulates the individual and collective behavior to best accommodate a life that devotes to pursuit the accumulation of capital. Even more, adhering to the ontology of the global agent latently refrains individuals from engaging in the promotion of generalized wellbeing of the ecosystems (and other humans, of course).

It follows that a different metaphor must take this place, Spivak (ibid) introduces the metaphor of the planetary accident as follows:

If we imagine ourselves as planetary accidents rather than global agents, planetary creatures rather than global entities, alterity remains underived from us away—and thus to think of it is already to transgress, for, in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous.

‘The planetary’ here inverts this notion of the global and the agent being separable thus situating all individuals as a part of the ecological realm. With this change in scope we argue for a blurring of the nation-state boundaries and a redefinition of the individual action-space that must lead to a more synergic entanglement of the human within itself, and within the earth as a system.

To direct the notion of the planetary accident into a behavior-regulating construct Spivak introduces the Islamic concept of haq which is meant to encompass a sort of “para-individual structural responsibility” and, at the same time, a structural right. Regardless of how much of this gets lost in translation, I interpret this as extending the autopoietic concerns of the human individual into the self-sustaining, self-replicating concerns of the Earth systems that sustain the human in the first place. So if feeding is one of such concerns, then making part of the processes that sustain it (natural ecosystems in general) is, by extension, also concerning to the individual. The introduction of this term is also meant to reference, with respect to Islam, what she calls the residuals of a nomadic past that thinks the earthly human habitation in community as planetary. This change in the collective behavior regulating maps induce the individual into an action space which embraces the transformations of the environment that can sustain worthy, meaningful human lives (regardless of a birth lottery), and the transformations of the environment that sustain the Earth’s systems. All of this is done by means of replacing capitalist or global labor with communal or planetary labor. And so must follow politics and culture.

3. Climate Engineering

Things are not going well. It is the case that human social coordination’s increasingly notorious capability to transform the environment simply aims at the wrong thing —the local accumulation of capital in networks of social metabolism. Whether it is an excessive release of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere or plastic particles in the oceans, the depletion of milennary water reservoirs or the vast deforestation of the rainforests, to remain business as usual is not feasible with respect to plenty of the Earth’s species’ window of viability (human’s for instance). Furthermore, as Barbara Muraca et al. accurately point out “There is a missing commitment of the Industrial World to cut emissions and it seems increasingly less likely that current political efforts will be able to stabilize temperature-rise globally at 2°C” from the 2015 Paris agreement. Moreover, “there is an anticipated emission overshoot that only slowly will come down in the second half of the century” (Muraca et al. 2018).

Climate engineering (CE) arises naturally when we realize it is this same capability to transform the environment that might produce a positive impact and perhaps even revert the damage. Except, it is not enough. Three of the most promising and developed CE technologies (Sulfate Aerosol Injection, Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage, and Afforestation) are neither viable —because they are parasitic on other biophysical systems— or convivial —because they can only be successful on a large scale and with modes of reproduction that imply concentration of power and the exclusion of those communities who are already the most vulnerable to and the least responsible for climate change itself. Therefore, technologies to control the climate alone are not enough (ibid). This is a very important conclusion from Muraca et al. which reinforces my ongoing argument that a profound change in the structural commitments of capitalist societies is non-negotiable.

Now this is not to be taken as a note to cease and desist but rather as evidence that our way forward must integrate CE with politics to achieve a rearrangement of the systems of social metabolism —with an outlook on coordination. Holly Buck revisits this in the context of the oil industry where the same technological infrastructure that is used to extract oil could be used to sequester carbon as the global economy allegedly transitions into more sustainable sources of energy (Buck 2020). Problem is, it is not clear that the right incentives for the financial interests of the oil industry elites will arise and, if such incentives come solely from the ‘carbon offset industry’, it is likely that this will not meet the convivial criteria either. This form of co-opting is certainly a worthy thread of thought to develop in both the right and left accelerationist agenda, yet it might counteract any chance to aim at solving both ecological prosperity and the abolition of layers of social oppression as entangled planetary concerns.

4. Seize the [Metabolic] Means

So far we have talked about worldmaking and how this is central to look at the socially construed landscapes of reality that regulate collective behavior, the planetary accident as a blueprint for a human-self ontology that is set to contradict that of the global agent (which accounts for the ecological catastrophe and several layers of human oppression), and the possibility to work towards sustainable systems of social metabolism through climate engineering but noting its inherent incompatibility with capitalist modes of production. Here I want to integrate these views into a compressed manifesto to seize the metabolic means upon which to preserve life on the planet and attain generalized wellbeing to the human selves. By this I mean to —perhaps poetically— suggest a planetary extension of the Marxist insignia that considers not only the means of production that satisfy human needs but also includes the means to foster the autopoietic concerns of the Earth’s systems.

As a preliminary step, business as usual must be completely dismissed as an option. Next, we must embrace permaculture in this ecology of possible worlds —and allow for it to engage with the dialectic change of material conditions— as the core activity to being human. That is, nurse the theoretical seedlings which populate symbiotic gardens in the collective landscapes of reality. Then set the education of the young as the primordial device to foster healthy societal arrangements. It is this transcendental intertwinement of theorizing which transforms the way we theorize and, theorizing which, in turn, transforms the material conditions that might spark the change we need. Let’s start with a taxative replacement of the planetary accident as the default human-self ontology and aim at collectively sketching the core components of wellbeing. Even when this might appear subjective and problematic, it is desirable —as far as we could ever come to grasp— to set wellbeing as a target to usher the lives of planetary accidents in every context.

In order to comply with haq in our status of planetary accidents we need to embrace human cooperation and reorganize human labor in order to attend to the autopoietic concerns of the Earth’s systems. We can start by prioritizing local arrangements that attend to the metabolic needs of ecosystems and communities and replace the status of technology as a global enhancer of capital and adopt tequiology (Aguilar 2020) as the communal development of infrastructure for the planetary realm to thrive. This way we engage in food production or school building the same as climate engineering or space exploration for the benefit of the planet as a whole. It is by means of communal labor and the egalitarian ontology of the planetary accident that we might have a chance to flourish. As long as we theorize, educate and create in accordance with haq. As long as we collectively usher both human lives and the Earth’s systems. This utopic possible world will materialize.

* control here is meant in the cybernetic sense of command or ‘steering the ship’.

Bibliography

Aguilar, Yásnaya Elena. “A modest proposal to save the world through ‘tequiology'”. (2020, December 9). Rest of World. Available at: https://restofworld.org/2020/saving-the-world-through-tequiology/. Accessed on June 4, 2021.

Buck, Holly Jean. “Co-opting”. In: AFTER GEOENGINEERING: climate tragedy, repair, and restoration. Verso Books, 2020.

Muraca, Barbara, Neuber, F. “Viable and convivial technologies: Considerations on Climate Engineering from a degrowth perspective”. Journal of Cleaner Production, 197, 1810–1822. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.159

Goodman, Nelson. (1978) Ways of Worldmaking, Indianapolis: Hackett, 2013.

Sachs, Carl B. “In defense of picturing; Sellars’s philosophy of mind and cognitive neuroscience”. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 18(4), 669–689. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-018-9598-3

Sellars, Wilfrid. “Being and Being Known”, Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association: 28-49. 1960.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Imperative to Re-Imagine the Planet”. In: An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 335-350. 2012.

Images taken from earthview.withgoogle.com by Alfredo Lozano.