Starting December 7th, David Auerbach will be leading The New Centre Seminar From Leibniz to Google: Five Paradigms of Artificial Intelligence. It will investigate AI within the framework of philosophy where it is not simply a technological artifact but rather a part of human conceptual armature. In this short introductory essay, Auerbach provides a background for his upcoming project and outlines some key ideas central to his research that will be further investigated and developed in his upcoming Seminar.

The history of computers did not start with Silicon Valley, nor did it even start with Alan Turing’s pioneering work in the 1930s and 1940s. In the modern age, the quest for computation began with the search for Babel: a universal language that could eliminate ambiguities and misunderstandings and bring humanity back to unity. Today, with the world more fractured and fractious than ever, we seem further from mutual understanding even though lines of communication are more present than ever.

Even in the absence of today’s technological glut, these problems have appeared repeatedly in human history. One particular historical crux lies in the 16th century interstitial period between the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, when rationalism peaked and the decentered universe, no longer with the Earth and humanity at its center, presented us with a gap that was to be filled not with rulers nor with gods but with impersonal, abstract ideas, from Cartesian geometry to the calculus. This period is frequently called the Scientific Revolution, but for the purposes of my research I prefer to term it High Rationalism: the embrace of impersonal, non-empirical ideas as the formative forces in the world, set next to and increasingly in place of Christian humanism. This transition can be portrayed another way: a replacement of the relationship between the individual and the personal, specific forces of an anthropomorphic deity with a new relationship between a homogeneous group of creatures and a set of impersonal forces conceived of as ideas. While Weber portrayed this movement as a “disenchantment of nature,” I propose that the notion of enchantment is misleading. Rather, the transition to the modern era is better described as a process of departicularization and large-scale quantification. The seminal work on the subject is Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money, on which I have written a brief commentary. Whereas Simmel saw money as a neutral vehicle of value, empty of content, his research applies just as strongly to the more fundamental substrate of numerical calculation, the foundation of computation.

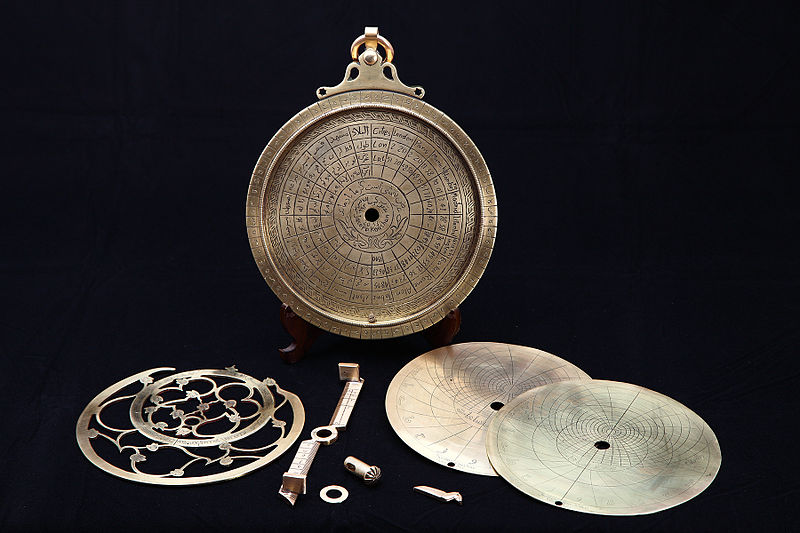

Leibniz, who simultaneously invented calculus with Newton, pursued the idea of calculation in not one but two regards. Leibniz’s development of mathematics went hand in hand with his dream of a machine that could answer any question put to it. The prerequisite for such a “computer” was not just the development of computing science, but the development of an ideal language in which these questions could be asked and answered with precision and perfection. This dream would not die until the 20th century, Kurt Goedel proved that some questions of mathematics could literally not be proven correct. Yet the conception of such a language for asking and answering such questions–a language that we tend to think of as taking the form of mathematics or logic–has been with us before Leibniz and remains with us today. Much has been written on the dream of such a perfect language; my own project is to study how the historical conception of that language has been influenced and conditioned by certain fundamentals of computation.

In my first book, Bitwise: A Life in Code, I examined the problems of computation from the vantage of my own experience as a software engineer, a career I abandoned in order to pursue my deeper dreams of writing and scholarship. In particular, I used Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language in order to examine the categorical and ontological structures (race, gender, and other demographic classifiers in particular) that are socially imposed on us, and I examined how computers favored and reified such structures.

Bitwise formed the first panel of a triptych, and this paper outlines the second, more scholarly piece, in which I will treat computation and algorithms not as digital artifacts but as human conceptual structures, out of which actual computing is only one manifestation and not even its most crucial. In this, I am influenced by the German philosophical anthropologist Hans Blumenberg, who believed that the fundamental substrate of human understanding lay in certain “absolute metaphors” such as light, water, fire, and other primitive and omnipresent concepts. To these, I wish to add several more: number, probability, and data.

While these three concepts are not visually concrete, I shall argue that the modern world rejects our efforts to conceive of it visually, and so we have been forced to fall back on a certain set of core mathematical and computational notions that have been with us since before Mesopotamian times. Their seeming newness owes only to the new technological forms they have recently taken. As ideas, they are as old as human history, though frequently the preserve of the elites. Edmund Husserl traced the evolution of this kind of scientific geist in The Crisis of the European Sciences, a phenomenological effort which American philosopher Wilfrid Sellars speculated could be naturalized.

These structuring metaphors of number, probability, and data have made themselves known whenever the scale of the individual and the scale of human society have diverged too far. We can term this the problem of modernity: how does one cope with the absoluteness of reality not merely being foreign to one, but also too large for one to address individually?

The idea of computation is tied less essentially to computers and more essentially to all actuarial and measurement processes which we employ. In particular, I am thinking of money and economic structures (Simmel), representative politics (Polanyi, Wiebe), and urban planning (Mumford). In other words, those areas in which subjects are treated beyond the scale of the single human.

I plan to trace the arc of these computational metaphors across the arcs of three periods:

- The High Rationalist period of the 16th century

- The post-Enlightenment period of the mid-19th century

- The dawn of computer science, circa 1925-1945

All three of these periods saw major advances in the mathematical and computational theory that presaged future technological developments.

There has already been some investigation of the cultural impact of scientific concepts in each of these periods. Paolo Rossi has separated the scientific from the occult in his work on Renaissance science. Ian Hacking pioneered such exploration in his historiographical work on post-Enlightenment mathematics. And cultural historian and mathematician Jeremy Gray examined the impact of modernism on mathematics in his book Plato’s Ghost: The Modernist Transformation of Mathematics.

In the latter work, Gray excavated a parallel between the aesthetic and philosophical currents of early modernism and the contemporaneous conceptual movements of mathematics. I posit a similar parallel, in which the universalization offered by mathematics shows its presence in the 17th century scholarly edifices of Robert Burton and Thomas Browne, in the 19th-century socio-political thought of Auguste Comte and Georg Simmel, and in the 20th century synthetic assemblages of James Joyce and Robert Musil. These works are not at base mathematical. They do, however, depend on the usage of the same absolute metaphors of number, probability, and data that simultaneously informed developments in computational theory. And in each stage, those absolute metaphors have been necessary tools for understanding the increasing scale of the world and the individual’s seemingly shrinking place within it.

James Beniger’s The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society is a classic attempt to understand the development of cultural ideas of technological industry in terms of the rhetoric surrounding them. I wish to push Beniger’s brilliant work one level deeper and understand how the logical structure of our everyday world is now irretrievably tied up in our notions of number, probability, and data. In other words, I wish to show how classically humanist these three notions truly are, and so dissolve the supposed division between the scientific outlook and the humanist outlook.