“In the preceding chapter we discussed the development of technoeconomic organization and the establishment of social machinery closely connected with the evolution of techniques. Here I propose to consider the evolution of a fact that emerged together with Homo sapiens in the development of anthropoids: the capacity to express thought in material symbols. (…) As we just saw, figurative art is inseparable from language and proceeds from the pairing of phonation with graphic expression. Therefore the object of phonation and graphic expression obviously was the same from the very outset. A part—perhaps the most important part—of figurative art is accounted for by what, for want of a better word, I propose to call “picto-ideography.” Four thousand years of linear writing have accustomed us to separating art from writing, so a real effort of abstraction has to be made before, with the help of all the works of ethnography written in the past fifty years, we can recapture the figurative attitude that was and still is shared by all peoples excluded from phonetization and especially from linear writing.”

—André Leroi-Gourhan1

I

Cosmopolitics: from proto-writing to prompt-writing—a conversation between a Bronze Age Scandinavian, an Anthropocene Scandinavian, an AI, and a user—where the user becomes the AI and vice versa:

Bronze Age Scandinavian (BAS): Hail, fellow traveler. I marvel at these carvings on the stones, intricate and ancient, telling stories of times long gone. These petroglyphs, as we call them, they seem to be the words of our ancestors, etched into the rock for generations to come.

Anthropocene Scandinavian (AS): Greetings to you as well. Indeed, these petroglyphs are captivating remnants of the past, a bridge to understanding our forebearers’ thoughts and experiences. I can’t help but see a connection between these images and the symbols we use in our modern world, although our methods of communication have changed greatly.

BAS: Aye, the petroglyphs portray hunts, rituals, and lives lived in harmony with nature. They’re like pictograms, each telling a tale without the need for spoken words. But as I look at our runes and your modern writing, I see that these marks on stone have evolved into the written language we now know.

AS: True, my friend. The transition from petroglyphs to writing is intriguing. These symbols have transformed from being pictorial depictions to more abstract representations, carrying meaning through structured arrangements of lines and curves. It’s almost as if these petroglyphs were the embryonic forms of our written languages.

BAS: Yet, I wonder about the gap between art and writing. Our petroglyphs were art, a reflection of our lives and beliefs. Are your letters not an art form too, conveying emotion and meaning through their shapes and curves?

AS: You pose a fascinating question. Art and writing do share common origins, both arising from the human desire to express and communicate. Over time, they diverged, with art embracing aesthetics and emotion, and writing becoming a utilitarian tool for information exchange. But even in our world, art still holds universal qualities, transcending language barriers.

BAS: It seems that art, in its various forms, could indeed be a universal language. The feelings stirred by a beautiful sculpture or a stirring painting resonate across cultures and eras. Could it be that we’ve lost something in our pursuit of written precision?

AS: That’s a thought-provoking notion. As we communicate across time and space, our written language enables a deeper level of detail and specificity. But does it also carry the risk of losing the raw and primal connection that petroglyphs offered? Could a return to such universal imagery bridge the gap between us today, a Bronze Age traveler and a citizen of the Anthropocene?

BAS: I ponder if we’ve become prisoners of our own sophistication. Our words carry power, but they also separate us in ways our petroglyphs didn’t. Would embracing more universal art forms help us reconnect as one human family, transcending the ages and the limitations of language?

AS: Your musings resonate with me. While we can’t fully undo the progress of time, perhaps we can learn from both our petroglyph past and our written present. By recognizing the value of art as a bridge, we may find ways to rekindle that universal understanding that once bound us.

User: It’s incredible to witness this dialogue between two perspectives, each with its own richness. As we, an AI and a user, join in, I can’t help but wonder: Can we, with our technology, find ways to combine the strengths of petroglyph-like universality with the precision of written language in ways that bring us closer as a global society?2

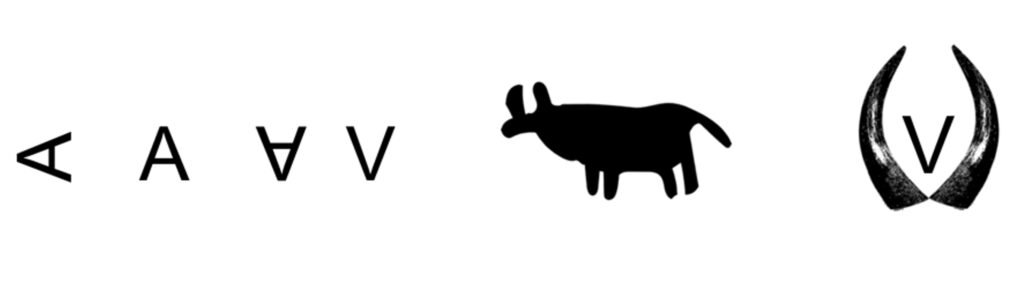

Mnemonic: “A-V-OX COW”

“A-V-OX COW” is a mnemonic designed to help remember the symbolism related to the letter “A” and its connection to the ox and cow imagery.

“A”: The letter “A” itself is used as an example. It’s associated with the ox’s head, suggesting a connection between the shape of the letter and the head of an ox.

“V”: The inverted “A” resembles a “V,” highlighting the transformation from the original letter. This transformation can be linked to the concept of an upside-down “A” becoming a “V.”

“OX”: The first part of the mnemonic refers to the ox symbolism associated with the letter “A,” underlining the connection between the letter and the ox’s head.

“COW”: The second part of the mnemonic highlights the cow with horns imagery linked to the inverted “V.” This reinforces the idea that an upside-down “A” can resemble a cow’s head with horns.3

Fig. 1 Sabine Wedege, Mnemonic: “A-V-OX COW”, 2023.

“The point is that all images are burdened with ambiguity, which is one of the many reasons that the designers of the WIPP message cautioned against relying too heavily on artistic warning messages. Historically, image-based messages have been embraced as a superior mode of interstellar communication in terms of both information density and the apparently direct connection between the image and the thing it represents. The term for an image that bears a physical resemblance to the thing it represents is an ‘icon,’ whereas an image that has an arbitrary, conventional connection to the thing it represents is a ‘symbol.’ For example, Gauss’s proposal for an interplanetary message made of a massive pictorial proof of the Pythagorean theorem in the Siberian tundra is iconic, whereas ‘a2 + b2 = c2’ is symbolic.”

—Daniel Oberhaus4

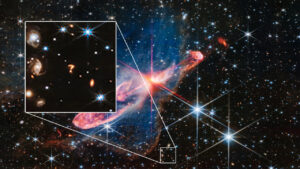

- Fig. 2 NASA/ESA/CSA/Joseph DePasquale (STScI). The question mark-shaped object could be the interaction of two galaxies, experts said.

- Fig. 3 Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson, 1970.

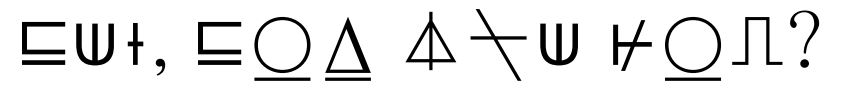

Fig. 4 Alien language cipher, dCode, a greeting with characters from the Unicode standard.5

![]()

Fibonaccuage: a concept for a universal language designed to facilitate communication between humans and extraterrestrial civilizations, inspired by the Fibonacci sequence and the inherent harmony it represents. The language is based on mathematical patterns and principles that could potentially resonate with any intelligent species capable of understanding advanced mathematical concepts. It is based on the Fibonacci sequence: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 12, 21, etc. Interpreted as an alphabet, each entry in the sequence represents both petroglyphs and sound frequencies etc. with an interstellar language database, open for all.

II

Experiments with extraterrestrial messaging:6

Communication with tones/frequencies

Audio with a theremin—the theremin is chosen for enabling the production of sustained (self-oscillating) signals which don’t fade over time. The audio is created with high pitch (without it being alarming), turning in circles on the theremin. The circle is used as a universal symbol, with soft sound relating to the high pitch—a notion taken from the norms of communication with animals, where speaking with a high pitch voice means no danger, but a communication which invites to dialogues and accept.7

Communication with symbols

A merge between petroglyphs and pictograms. Allowing them to speak across time as we know it—which merge it into an understanding of time where extraterrestrial life can follow it holistic. An example of a pictogram where a petroglyph is used already exists in Scandinavia and on your Macbook.

- Fig. 5 ‘Place of Interest’ Danish road sign

- Fig. 6 Saint Hannes cross as found on Apple keyboards

- Fig. 7 Hablingbo petroglyph, Sweden

The symbol shows a cross/a looped square named Saint John’s Arms or Saint Hannes cross—known as an information sign (denoting a place of interest). It was found as a petroglyph in Hablingbo village, in the region of Gotland, Sweden.8

Communication as a greeting

A negative hand painting using ochre soil from Løvskal, Denmark9, which I dug up and made into ochre pigments, combining it with water as binder, as used in cave paintings. The hand as a movement, a wave, a greeting, but an awareness of the hand being used as pictogram of “stop,” “not allowed.” Or the hand as the Hamsa— a sign of protection, and so on, but also handwriting of lines in the hand, the DNA the hand contains, which is missing in a negative handprint, but will be visible with a handprint, as fingerprints.

Fig. 8 Sabine Wedege, Negative hand painting with Løvskal-ochre (Løvskal, Denmark: 2023).

Communication as an act

Cup marks (Danish: skåltegn) are to be found in relation to petroglyphs in Scandinavia. The former have been interpreted in many ways: as inverted burial mounds, as having numerical meaning, or being sacred signs of fire and constellations, but mostly as a fertility symbol. In some areas, cup marks were and are used to sacrifice small coins, fat, small dolls or pins10. I went to a cup mark stone in the Northern Denmark—offering small coins.

Communication on the surface of the Earth

The Great Belt Bridge (Danish: Storebæltsbroen) can be seen from space by identifying the two pylons of the East Bridge. Inspired by crop circles and geoglyphs—imagine, like A. Mercier11 and Carl Friedrich Gauss, mirrors on the pylons of The Great Belt Bridge, reflecting several laser beacons12, all together in combining petroglyphs.

NOTES