Note: This piece was co-produced as a dialogue in the manner of a feedback between the authors. They reacted to each other’s thoughts on Law about Space while having as a single rule that each would use a different language as a tool of communication. Zé would use written text, whereas Artemis would use visual expressions.

When (in what is, in terms of internet temporality, now a very long time ago) Lawrence Lessig famously stated that “code is law”, pointing out that the problem of the regulation of cyberspace wasn’t so much that of how State law would normatize it, but of how it would normatize itself through its own structure, he spoke of program code as “the architecture of the net”. No less important than the legal analogy suggested by the common relation that both law and IT share with types of code is the architectural metaphor. That is because in computer code, unlike what is the case in codified law, but precisely like what is the case in architecture, abstract norm and concrete coercion of conducts are not separated/mediated but coincide immediately.

The question here is not how the architecture of the Net will make it easier for traditional regulation to happen. The issue here is how the architecture of the Net – or its “code” – itself becomes a regulator. In this context, the rule applied to an individual does not find its force from the threat of consequences enforced by the law […]. Instead, the rule is applied […] through a kind of physics. A locked door is not a command “do not enter” backed up with the threat of punishment by the state. A locked door is a physical constraint on the liberty of someone to enter some space. (Lessig, 2006, p. 81)

The norm/coercion distinction is fundamental to modern codified law. A norm is an abstract ought such as “do not pass through this door”. For it to be a legal norm, failure to comply with it must be associated with an organized coercive response: “if you pass through this door, you must be put in jail” or “… pay a fee”, etc. But the act of coercion in this case has no direct correspondence to the conduct originally predicted in the norm: you may go to jail or have to pay a fee, but that doesn’t prevent you from passing through the door in the first place. In modern law, norm and coercion are logically and temporally separated.

When it comes to computer code, the opposite is the case. If the equivalent of “do not pass through this door” is coded into the architecture of a digital space – if, say, access to a certain digital object is denied to certain users under certain conditions – the conduct of going through that digital door becomes, under those conditions, unavailable. The coded norm is concretely instantiated as architecture, so that, instead of there being first a conduct in disagreement with the norm, and then some act of coercion in response to it, there is an immediate reconfiguration of the set of conducts available.

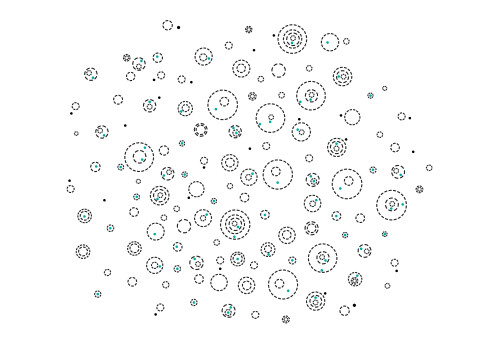

Green dots represent prosecutions

Deleuze (2013, p. 299, translation ours) attributes to Guattari the image of a city – much less futuristic today than it was in the early 90s – in which each inhabitant would carry an electronic card that would provoke the opening of certain doors around the city, but that could as well, under some circumstances, be refused: “What counts is not the door, but the computer which detects the position of each one, licit or illicit, and operates a universal modulation”.

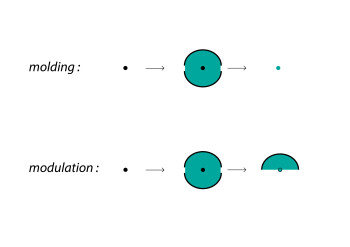

In that text, his “Postscript on the Societies of Control”, Deleuze (2013) is busy differentiating what he calls control societies from the disciplinary societies described by Foucault (1975). The notion of modulation appears as opposed to the molding operationalized by disciplinary architectures such as the prison, the school, the barracks, the hospital. We can think of a school as a factory which imposes the form of the ideal student onto the amorphous mass of young bodies which come into it. The same with the barracks-soldier, prison-prisoner, hospital-patient pairs, and so forth. This molding operates by a relation between the architectural level of those buildings (which share a common diagram, having their paradigm, according to Foucault, in Bentham’s Panopticon) and that of the individual bodies. In modulation, on the other hand, there is no pre-established mold, but a “self-deforming molding that changes continually, at each new instant” (Deleuze, 2013, p. 225, translation ours). Power doesn’t operate so much by the limitation of movement, but through a self-adjusting conduction – a tweaking according to the variables of each situation. While in disciplinary power a transcendent norm is imposed upon conducts, in control norms are to be discovered in the conducts themselves. In both paradigms there are walls and doors which instantiate concrete norms, but a very different architectural diagrammatic is at play.

Even though he succeeds in differentiating control architectures from disciplinary ones, Deleuze (2013) curiously alludes to the archaic mode of power which, already in Foucault (1975), would have been gradually supplanted by the disciplines – that of sovereign law – when he refers to the licit/illicit distinction, as seen above. What would “count” for modulation would be the “licit or illicit” character of the user’s “position” at any given moment.

Though Deleuze never develops on this topic, it is clear that a very different concept of licit/illicit from that of sovereign law is implied. In control architectures, there is no previous definition of a general type of conduct (or position) considered to be against “the law” in general, coupled to the expectation of prosecution and the eventual imposition of a sanction. It is not the fact of being in front of a door, in general, that is considered illicit, neither just the fact of this specific body being in front of this specific door, but an entire singular and contingent context, an entire network of relations which makes the possibility of going through that door, at that singular juncture, analogous to “illicit”.

In control, prosecution doesn’t have a beginning and an end, where a case would be closed and the licit/illicit character of the relevant conduct would be determined. Prosecution becomes continuous and, as the word implies, follows one around. Whether your situation is licit or illicit can change at any given moment – this is what Deleuze means by “position” – without a necessary relation to any well-defined conduct, but rather as a function of a multiplicity of variables that easily escape comprehension. Like in Kafka (1998), prosecution has no clear limits, no clear material cause, no clear accusation or defense, no clear criterion of judgment. Prosecution is experienced, instead, in ever-changing architectural interfaces.

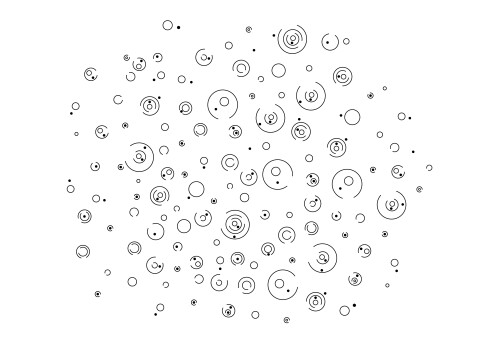

Zoom in to each particle:

The emergence of the architectural disciplines in parallel to abstracted modern law is explained by the fact that the abstract recognition of the free individual does nothing to produce the type of bodies that could functionally fit that position. As Schmitt (2006) emphasizes, law cannot be applied over chaos, so that a certain concrete pre-ordering is required. The individuated subject is meant to move out of the disciplinary architecture as a self-contained entity, even if only in order to move into a next institution (from school to barrack, from barrack to factory, from factory to hospital). In control, individuation is not the point. The mold doesn’t inscribe form on the body and then fall behind, but rather exists in constant bilateral modulation with it. Body, code and architecture are entangled.

While juridical-disciplinary architecture produced citizen-subjects as individuals, contemporary algorithmic control produces user-profiles as dividuals. Individual conducts were interpreted and governed in the context of the integral individual subject – a conduct was integrated with all other conducts of the same individual. Dividual conducts, by contrast, are governed or controlled not in the context of other conducts by the same subject, but of the same conduct by other, say, “would-be” or “quasi-subjects”. A user’s use of an app is (paradigmatically) governed not in the context of the “same” user’s use of other apps (since user-positions are contingent to each app, to be a user of various apps is, rigorously, to be various users), but as inscribed in a probabilistic curve along with analogous uses by multiple dividuals.

In this context, the emergence of user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) in business and technical discourse expresses the operational diagrammatics of the emerging anthropological – or de-anthropological – platform-interface-user apparatus. If UI and UX seem at first to appear as separate correlated endeavours, UI being the object of engineering while UX would be an object of knowledge, the tendency in algorithmic control is towards a realization of the indiscernibility of interface and experience, and the consequent emergence of a full-blown engineering attitude towards user experience as such.

Produced in this manner, UX is rigorously not the experience of an individual (with mind-body correlation etc.), but the experience of a probabilistic and correlational graph that encompasses a series of dividuals. UX is, properly speaking, the experience of this transindividual entity (the user) which takes on its own mode of being.

![]()

Contagious Contingent Jurisprudence

Each particle-user correlates with each other, shaping the user experience of the other user(s) and thus the interface with its laws/rules.

Of course UX-UI (or UIX = user-interface-experience = user experience as interface = user interface as experience) isn’t simply a free-flowing aesthetic experience, but a normative/nomic experience. It is normative both in the sense of being constrained and structured as experience by an assemblage of relatively concrete and relatively abstract norms (though never absolutely abstract), i.e., of being normed, but also of being nomogenic, inasmuch as use itself produces and reproduces norms. It is both an experience of continuous prosecution, and, in that sense, a virtually nightmarish or kafkaesque experience, and also a direct experience of constituent power. The ideal paradigm of the latter might resemble a “lucid dream” in that, in it, will is experienced as a concrete norm.

We have pointed out how modern law functioned by separating abstract norm and concrete coercion, but a concrete, architectural and directly existential conception of norms can be found in an anti-modern modern legal theorist like Schmitt (2003, p. 42). In The Nomos of the Earth, norms are concretely instantiated and shown in the forms of the earth itself: “She contains law within herself, as a reward of labor; she manifests law upon herself, as fixed boundaries; and she sustains law above herself, as a public sign of order”. For Schmitt, law is “bound to the earth”, often as architecture, e.g. in the form of “fences, enclosures, boundaries, walls, houses, and other constructs”.

Schmitt (2003, p. 42-43) then moves to contrast the earth to the sea, which “knows no such apparent unity of space and law”. The sea, unlike earth, “has no character” in the sense that the uses of human life and work do not leave any fixed traces on it. Unlike the earth, which is free until it is “taken” by a certain nomic ordering, the sea is always free as a consequence of its anti-architectural nature. It is pure flow, change and dissolution.

With the emergence of cyberspace as a new “free soil” in the planetary nomos, the question of its nature and consequent appropriability has been put forth in different ways. In the early days of cyberspace, the question seemed to be either how to save it from being “taken” by external interests (as a “soil” that should remain “free”), or how to demonstrate that it was essentially immune to appropriation, as, e.g., in John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace”, very much like a “free sea” in the sense of being too dynamic for any permanent nomos to be inscribed on it.

Cyberspace and the sea share, of course, the theme of navigation – “cybernetics” comes from the greek “kybernetikós,” meaning what is pertinent to kybernáo, to steer, to navigate or to govern. So cyberspace, like the sea, can be thought of as the space of navigation. But, while the “free sea” was defined as indifferent to human uses, fully natural (pertaining to physis) and in no way constructed, cyberspace is thoroughly constructed (pertaining to nomos), thoroughly architectonic, and thoroughly modulated by its uses. In that sense, cyberspace may be better construed not as the space of navigation, but as navigation-space and governance-space – a space in which navigation (governance) and construction (constitution) coincide.

In the cybernetic cosmopolitics that ensue, antagonistic philosophies and their correspondent pragmatics appear. While 90’s CCRU accelerationism saw cyber as a thalassic, “hydraulic” and anti-architectural force equated with the death drive’s “tendency to the dissipation of intensities” (Land, 2011, p. 283), contemporary left/accelerationism construes planetary computation as a normative or nomic, gaseous (geistig or cloud-like), but also materially built and essentially architectural form, whether à la Negarestani (2018) or à la Bratton (2015). L/acc projects onto computation a normative, constructive attitude, even if scaling from the local user-level to the abstract strata of platforms remains a theoretico-practical problem.

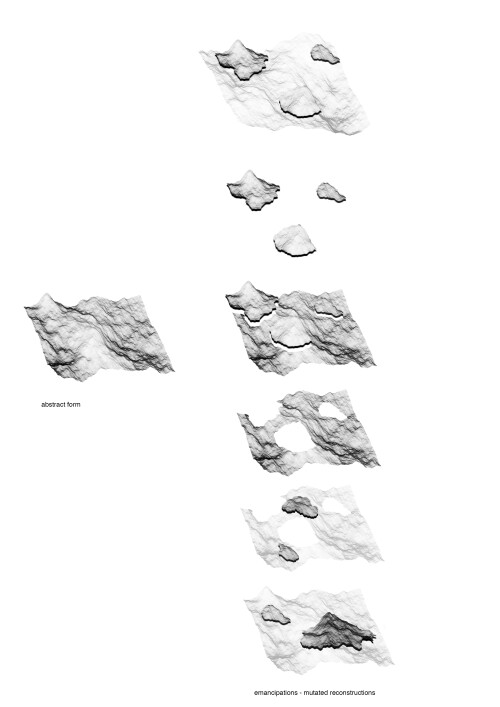

In the current phase of technocapitalism, platform architecture tends to mitigate the constituent potentiality of use. Interfaces are built so as to offer affordances for the creation of content – every user is a precarized “content creator” for platform companies – but not so much for the creation of form. This separation between the production of content and that of form is in the very foundations of contemporary capitalism, with its obsessive mining of immaterial labor. In this context, the figure of the power user – a user who is not only a content creator but a form creator, or, more precisely, who is able to intervene on the diagrammatic level on which form and content are entangled – appears as a paradigm for a (quite different) successor, in a post-liberal platform democracy, to the democratic citizen.

It would be relatively easy to pose the problem of what platform architecture “we” want, and how to implement it, if there was anything like a “we” already given on the level of action on which such questions could be posed. Not only is it the case that there doesn’t seem to be any big “historical subject” available for such a task, and no pre-established path affording the scaling up from the lower user-levels to a general level analogous to that of State sovereignty, but neither the individual reflexive subject seems to be available as an agent (in any familiar sense) at the place of the user – which now lends itself to pretty much any human or non-human being (Bratton, 2015) – nor does there appear to be a guarantee of the existence of a sovereign throne at some kind of structural pinnacle to which any to-be-determined agent could aspire.

This doesn’t mean that there is no agency, or that there are no processes of individuation taking place at various points in the geo-technological apparatus. If there is no privileged stratum on which to expect anything, this also means things can start at any level, and then scale up or down or sideways from there.

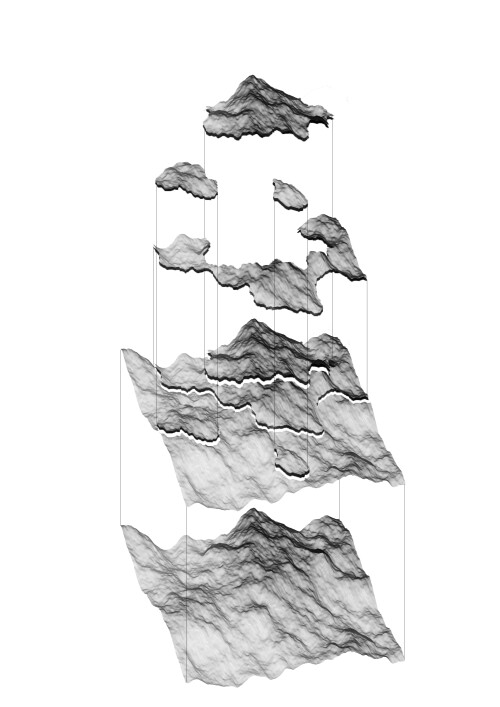

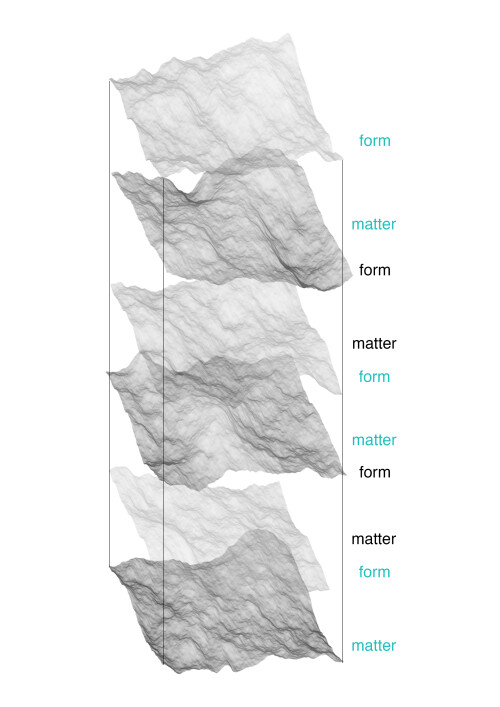

Abstraction, in this context, means platforming. At any given level, affordances are guaranteed by the material stabilization of a lower level, so that relevant functions can be considered in a simplified way on the level above. The lower level appears, in relation to the upper level, under the guise of “matter”, while what happens on the higher level appears as “form”, but the latter could, in turn, appear as “matter” in relation to a yet higher level. To produce powers of action on each stratum supposes an intervention either on lower strata (as matter) or higher strata (as form) so as to produce and maintain certain relations, considered as causal relations (cause and effect) when looking “down” and as normative relations when looking “up”.

In this sense, to consider law as architecture is also to consider that any possibility of effective legislation, i.e., effective coding, on one level of abstraction, depends, as Schmitt had already suggested, on a certain material order – an infrastructural order maintained at a lower level of abstraction. The power of abstract form, i.e., of intelligence, though, lies precisely in its capability of emancipating itself from any parochial order inasmuch as it can always reconstruct different conditions for its own implementation.

References

BRATTON, Benjamin. The Stack: On software and sovereignty. Cambridge; London: The MIT Press, 2015.

DELEUZE, Gilles. Conversações: 1972-1990. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2013.

FOUCAULT, Michel. Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison. Paris: Gallimard, 1975.

KAFKA, Franz. The Trial. New York: Shocken Books, 1998.

LAND, Nick. Fanged Noumena: Collected writings 1987-2007. Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2011.

LESSIG, Lawrence. Code version 2.0. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

NEGARESTANI, Reza. Intelligence and Spirit. Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2018.

SCHMITT, Carl. The Nomos of the Earth in the international law of the ius publicum europaeum. New York: Telos Press, 2003.

_____. Political Theology: Four chapters on the concept of sovereignty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.